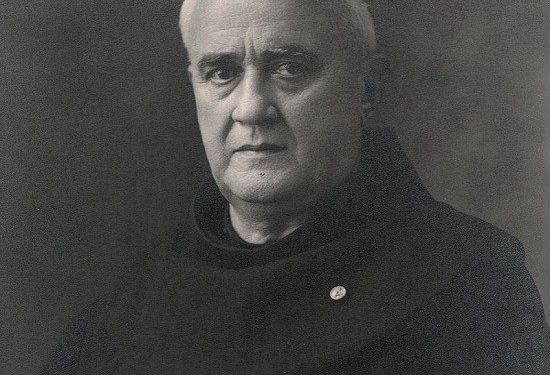

Dr. Aurel PLASARI

Part Two

Memorie.al / In the Albanian culture of the first decades of the 20th century, theoretical-aesthetic thought underwent its first qualitative leap, which would become particularly palpable during the period between the two World Wars. As in many cultures with a similar fate, the development of this thought in Albania is characterized primarily by the intertwining—which seems permanent—between literary and art criticism, and between the history (respectively theory) of artistic phenomena and the analyses inherent to aesthetics as a specialized discipline. The factors conditioning the spread of aesthetic ideas, as well as their imposition, in the Albanian culture of these decades are numerous and complex, if not also implicated with contradictory elements that can influence both the dissemination and the expansion of these ideas.

Likewise, Albanian culture, in the turbulent hypostases it underwent during the ’30s–’40s and especially after 1945, by refusing to listen to Fishta, has caused its own philosophical thought one of the most irreparable damages. If “Longinus” was a victim of the tradition of ancient mediocrity – a victim of an indestructible tradition of mediocrity that still triumphantly waves its tattered flag in so many battles – Fishta’s theoretical-aesthetic thought has also fallen in Albania.

Since this is not the place to dwell on the reasons why so little has been written about Fishta’s aesthetic (and critical) contribution, I recall only one truth: that his theoretical-aesthetic thought has not enjoyed, and continues not to enjoy, the sympathy (or understanding) of Albanian writers and artists. The courage, clarity, advanced level, and even the originality of his working methods, as well as the diversity of the problems he discusses and brings into question, undoubtedly testify to a creative power that transcends the ordinary. It is not difficult to understand why such powers stir aversion, sometimes even among the prominent personalities of a culture. Furthermore, note this: the very fact that the anti-Fishta aversion is proclaimed loudly, with excessive fury, makes one suspect a guilt complex among the detractors… I do not exaggerate when I say I have met only one or two intellectuals over the age of 40 who show any interest in Fishta’s philosophical thought. I also affirm that I have met many young people who “boast” that they do not understand, do not grasp, or simply do not accept the thought in question.

On the other hand, it must also be said that Fishta’s theoretical-aesthetic thought counts admirers among those rarely encountered in the Albanian cultural world; L. Poradeci, who dedicated his work to him with devotion: “To the Poet militans et meditans“, is but one of them. Understandable warmth, an almost unreserved adherence, and a special readiness to penetrate deeply into this thought make these admirers enviable.

For Albanian culture in general, it can only be called a misfortune that a significant portion of Fishta’s aesthetic (and critical) thought, much like the best of Konica’s, had no particular resonance, was poorly received or not at all, and, above all, was violently severed from the normal currents of Albanian philosophical thought. Let us admit that in philosophy, delays are catastrophic, while ruptures are true ruin.

If one compares the current state of philosophical thought with the tradition it was forced to abandon, the cost of that ruin is not light. To provide an example, I recall that writings such as Sketch of a Method to be Applauded by the Bourgeoisie (1903), Essay on Natural and Artificial Languages (1904), and The Greatest Mystification in the History of Mankind (1904) etc., by Konica, still retain an originality of thought and even relevance in a culture like the French one.

In The Mystification, for instance, by denying the “linguistic” character of Oriental languages as such and elaborating on their cryptographic nature, treating their grammar as a “pornographic treatise,” and even questioning the decoding value of the biblical version of the “Seventy” (Septuagint) etc., beyond the understandable bizarre aspects for the time, Konica introduces one of the most interesting theories in this field: that of linguistic-aesthetic structures in Orientalism. Similarly, in the Sketch, he treats a purely aesthetic subject.

Following the theses rose in the Essay, responding to the partisans of Esperanto – an artificial international language – Konica gives importance to the reader, starting from the trinity: literary work – author – reader. “It is undeniable,” he notes, “that the individual with average (médiocre) artistic formation and, moreover, filled with prejudices – the bourgeois among all – applauds the moral significance more than the beauty of a work.” With his insistence on the role of the receiving instance in the evaluation of artistic creation, Konica becomes one of the precursors of what is today called the “Aesthetics of Reception,” etc.

To understand a thinker, as well as a system of thought, usually means establishing connections between them and other thinkers, as well as other systems of thought, suspected of being similar. Such a procedure rarely fails. For example, J. Mato thought he was “on the mark” by establishing the link between Fishta’s aesthetic thought and “Christian philosophy”: “He concentrates on some general theses of Christian philosophy…” (Krijime, 118) “The theses and viewpoints are elaborated in an original way, based on Christian philosophy…” (ibid. 122). Could he be unaware of what is called “Christian aesthetics” during the Middle Ages and, further, “Christian Romanticism” in aesthetics?!

Even in the case where Fishta analyzes the primary forms (primordialis) of objects, created by the “First Cause,” for today’s esthete, he does this “starting from Christian philosophy” (p. 118). Does the modern esthete not know, perhaps, that the principle of the “First Cause” (prima causa) is recognized in philosophy as a purely Platonic principle, only later adopted by medieval philosophy and, thereafter, by German idealism? In Fishta’s case, for example, it is easily observed how, as early as the 1913 writing, by dividing the “levels” of civilization development of peoples according to their belonging to the five periods of the development of their arts (I. the poetry of the Hebrews; II. the poetry of the Indians and Egyptians; III. classicism in ancient Greece, etc.), he provides one of the original developments of Hegel’s theory on the dialectical evolution of art in the history of human culture.

Meanwhile, in other writings, one can discern a mastery of the theses of one of Hegel’s “formalist” opponents, such as J. F. Herbart. In cultural polemics with the “journals of France,” by pointing out the links between Greek tragedy, Greek mythology, and religious rites, on the one hand, Fishta’s writings remind one of theories that would be elaborated at roughly that same time by philosophers like Jane Harrison under the influence of Sir Frazer’s theories.

On the other hand, by bringing into question pathological, physiological, and craniometric data, by rejecting them and, simultaneously, through clear cultural-anthropological implications throughout the argumentation, Fishta appears as a precursor in the efforts to elaborate a general theory of human culture (“cultural anthropology”), which would be realized in the ’20s–’30s by E. Cassirer as the neo-Kantian theory of “great symbolic forms” in culture.

Historical judgment has become so natural to us and appears, most of the time, so correct, that we do not hesitate to employ it at every opportunity. However, in the case of Fishta’s theoretical-aesthetic thought, as well as his system, I do not believe one can reach any valuable result through this path. Isolated in research, both as an object and as a method, establishing the connections of Fishta as a thinker becomes difficult. It is as if the comparisons, instead of bringing him closer, push him away, alienating everything in his thought that might be original—that is, incomparable.

As learned indirectly from a letter of Fishta’s own addressed to one of his political detractors in 1922, he had sent one of his theses to an English philosopher specializing in aesthetics and ethics at the University of Cambridge. In his reply, the Englishman states that Fishta’s aesthetic theory has filled him with “a true spiritual enthusiasm,” qualifies it as “new and entirely original,” while greeting Fishta as the “founder of an Albanian philosophical school.” Which theory (or thesis) could he have been referring to, I wonder?

The original “zones” in Fishta’s theoretical-aesthetic thought are not few. It is enough to read Aesthetic Notes: On the Nature of Art (1933) and there remains in one’s mind, at the intersection of philosophy and the psychology of creation, the theory of the “two universes.” In the human mind, according to this theory, there exist two universes: the visible or real one, and the ideal one, created by the mind itself through the power of imagination. Through sight and the other senses, the mind perceives and knows the visible universe with all it encompasses; through imagination, the mind gathers the images of the visible universe, with all the impressions that objects have been able to leave upon it.

In this way the mind, step by step, creates within itself the other universe, the ideal one. For Fishta, this ideal universe is more open and larger than the real universe, since through imagination the human mind can separate or join the parts of one object with those of another object and thus obtain a new individuum in its own universe; such an acquisition is, for Fishta, the hippogriff (the winged horse) which in the real universe does not exist. Describing the ideal universe of the artist, he points out that the artist’s mind has greater abilities than others, in terms of intuition and imagination, and that his ideal universe is larger and more beautiful than that of others.

Or, here is another interesting thesis, also from Aesthetic Notes: “Someone once asked Raphael, asking him from where he drew that so convincing beauty of his ‘Madonnas’: ‘Da una certa idea,’ Raphael replied. Thus not from any ordinary idea of things as they are found in nature, but from an idea conceived through intuition in the artist’s mind about the object, as the latter is found enlarged in the fantasy. Therefore those are wrong who say that art is an imitation of nature; as could be proven even by photography, which certainly presents nature more faithfully than any famous or renowned artist, and yet it is not art. Furthermore, it is seen that the greatness of the idea of the object of the artistic work is conceived by the genius, or rather by the soul, an individual, simple and reasoning substance – let the modern idealists and materialists say what they will, more or less grandsons and great-grandsons of monkeys, not so much because many among them consider themselves to be of the monkey’s kin, as for the fact that they all – almost like the monkey – imitate the worn-out theories of times past…”

When one reads this “note” full of critical depth, one asks oneself if many Albanian art critics, who worry about the “theory of reflection” and strive for the “redefinition of the issue of reflection” from the ’60s onwards – even boasting of the merit that they have supposedly “expanded” this theory also with the “element of creation” and have invented “transformed reflection” etc., etc. – truly bring anything new compared to what Fishta knew and wrote in the ’30s? Or compared to the way Fishta presented his own theory? With his “rebel” assertion that the theory of imitation (mimesis) was nothing but a “worn-out theory”?

The acceptance that in philosophy delays are catastrophic, while ruptures are true ruin, should be made not to evoke ill-will, but to courageously accept a situation and find the ways to change it; or, at least, to improve it.

For a modern student of letters, Fishta would represent a synthesis phenomenon: a synthesis of a morality, of a classical world (“No art can be more beautiful than the classical,” Hegel) and simultaneously modern, of an entire mythology in Albanian culture. Through Fishta, the synthesis of speculations (speculatio) on art is realized in our country, the synthesis of passionate struggles over the literary language, the synthesis of an aesthetic (and critical) thought of an entire generation and, above all, a startling synthesis of metaphysical and positivist tendencies of the time.

The study of his thought, alongside the study of his fictional work, would provide the mental instruments not simply to complete teaching, but to give a direction to the transmission of literary scientific knowledge. The fact that Fishta was constituted as a “universe” of knowledge was not something extraordinary for his time. The classical schools, which today we call “clerical,” cultivated the ancient tradition where children, from the age of eight, began to learn, for example, rhetoric. There was nothing to be surprised about that a boy like Zefi i Ndokës (Gjergj Fishta), at the age of thirteen, knew Virgil’s Aeneid by heart, just as the seminarian student of Fishta knew his Lahuta by heart. For the formative system of those schools, learning and studying became second nature, transformed into a way of existing.

Nothing to be surprised about, then, if in the “universe” of a thinker like Fishta, formed in this way, thinkers of all times are revived, starting from those of Antiquity, such as Demosthenes, Plato and Aristotle, Cicero; to those of the Middle Ages, such as Averroes, Saint Augustine and Albert the Great, Saint Thomas Aquinas and Saint Bonaventure; to those of the Modern era, such as Scotus, Bossuet, French encyclopedists and German rationalists, Rousseau, Taine, Benjamin, Rueb, Herder, Cantu, Müller, Fornari, Lowth etc.; without forgetting anthropologists such as Virchow, Pittard etc., albanologists such as G. Mayer, G. Schirò, N. Jokl, A. Schmaus.

An entire constellation of works and authors revolves dizzily in such a “universe,” from the poetry of the Assyro-Babylonians to the Mahabharata and Ramayana, from Firdusi’s Shah-Nameh to the poetry of the Egyptians and that of the Hebrews, from the Song of the Nibelungs to Fingal, from the Bible to Hesiod’s Titanomachy, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Pindar’s lyrics, the tragedies of Aeschylus and those of Sophocles, the comedies of Euripides and those of Aristophanes, the idylls of Theocritus, Ovid’s elegies, Horace’s Epistles, Virgil’s Aeneid and Bucolics, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Petrarch’s Canzoniere, Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered, Ariosto’s Satires, the epic of the South Slavs, Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Shakespeare’s theater and that of Calderon, Gundolic’s Osman, Milton’s Paradise Lost, Moliere’s comedies and those of Goldoni, Metastasio’s essays, Eschilbach’s Parzival, Goethe’s Faust, Monti’s tragedies, Schiller’s Homage to the Fine Arts, Chateaubriand’s Atala, Manzoni’s Adelchi and Sacred Hymns, Lord Byron’s poems, Heine’s Winter’s Tale, Leopardi’s The Song of the Broom, Ugheti’s Saint Francis, the songs of the Greek klephts etc.

But also works of art and great world artists, from the Acropolis and the Parthenon to the Roman Forum, from the Flavian Colosseum to Saint Peter’s in the Vatican, from Phidias’s Aphrodite to Raphael’s Apollo Belvedere, the Cathedral of Reims and that of Cologne, Notre-Dame of Paris and Westminster Abbey of London, Saint Paul’s Cathedral and the Duomo of Milan, Murillo’s Madonnas and Brunelleschi’s arches, Da Vinci’s sculptures and Bramante’s works, Palestrina’s Miserere and Bach’s Introits, Mozart’s Requiems, Viadana’s Masses and those of Haydn, Rossini’s Stabat Mater, Beethoven’s Passion, Wagner’s Parsifal, Parzanese’s The Blind Man etc. etc., as if to instill in the mind the perception that the creations of Art were the forty days of the blessed life of Nature!

Even the correspondence of such a thinker – of which we have inherited (to this day) only that small bundle kept jealously in the secret archive of his intimate friend Father P. Dodaj – is presented as woven with titles of works and names of authors, with comments and judgments, observations and evaluations, even with a wit (esprit) that flashes suddenly before you: “Boniface VIII was pope, but for all that he must stay in Hell, at least until the day of judgment, since he was condemned there by the little god Dante Alighieri”; “I had two occasions to hear Gentile in a space of two years. He kept saying the same thing over and over, right then and there. I don’t know how, but he drove the thought down in a spiral, like a drill (travello), as if he were boring into the mind. Thus, you know something, and you say it without ceasing, until it repeats itself”; “Here in New York I have heard Arthur Kreisler from Vienna playing the violin, currently the greatest violinist in the world. I reckon he played eight times better than that Friar of Plani in the year 1918…” etc.

The concentration of an immeasurable mass of information from the fields of art and literature, as well as from world theoretical-aesthetic thought, might today seem difficult to imagine for a writer or artist formed in contemporary schools. If we try to compare Fishta’s knowledge with the knowledge of each of us, he might seem like a colossus. It can be said with certainty that, for his time, he knew everything or almost everything from the fields of art and literature. That Englishman (mentioned above) must have sensed something when he wrote to him: “Perhaps little Albania, which until yesterday had remained outside the ‘mill’ of modern civilization, will manage to teach Europe the path of true knowledge…”

This is also a reason why it has seemed unacceptable to me, and will continue to seem so, that in the structures of the courses of a faculty of letters (or philosophy) Fishtean studies are missing. Such a course, of Fishtean studies, would function as a backbone in a school system with a humanist direction. Fishtean studies are an object that incites, that provokes.

Fishta’s theoretical-aesthetic thought presents problems that you might have grasped intuitively, but to which you have not been able to give a name. His solutions move along that cultural-historical path (the Christian path, if one wishes), along which modern European culture continues to break through. The aesthetic (as well as critical) thought summarized in this anthology thus appears as one of the fascinating testimonies of that great Albanian thinker, one of the greatest our culture has ever had.

The publication (and republication) of this thought today becomes an indispensable condition for reclaiming the values hidden or alienated from our culture. In this sense, in our cultural environment, where every publication or republication of a small booklet is spoken of as an “important event,” the publication of this thought will constitute, at the very least, an event. I do not know what the interval is for the publication and republication of good works, because the others are republished without ceasing (“right then and there”), until they repeat themselves. / Memorie.al

(Original title: FISHTA MEDITANS)