By Islam Spahija

Part Two

Memorie.al / In Kaush, almost every day there were transfers or new convicts arrived; that hall there was a temporary hostel, for those who had just received their sentence and were waiting for the destination, where they would serve it. One day, while asking the newcomers as usual, I met an elderly man. His name was Lec Sahatçia. A sensation: “Are you the one whose name is on the ‘Lista dei collaboratori’, of Cordignano’s ‘Italian – Albanian’ dictionary”? – “Yes, my own”. How many times had I seen this name, when I picked up that dictionary! It appeared among other bright names, such as; Dom Ndre Mjeda, Dom Nikollë Gazulli, Dom Ndre Zadeja, Hamid Gjylbegaj etc…! Third in line, former Dom Lec Sahatçia, with the note: “Parroco di Blinishti (Mirdizia), sopratutto per molta parte della lettera “S”. Now this man was suddenly appearing before me and I would not part from him, except at the moment when “Charon’s boat” would take us away from there.

Continued from the previous issue

AHMET KOLGJINI

It has not been long since Ahmeti left us forever and, although we know this, the feeling of love and respect does not let us believe that he is no longer among us. The only thing that does not die is the truth, says a wise saying. He always told the truth, so in this sense he remains immortal. Let us do the same as him; let us tell the truth about him.

“We are nothing but our acts” – wrote Jean Paul Sartre and, truly, people’s lives are inseparable from their work. So, talking about Ahmeti is the same as talking about his activity.

Perhaps it is one of the greatest artistic pleasures to be able to make a portrait of a deeply spiritual figure, such as his. Aware of the difficulty and responsibility that such an undertaking poses before us, we (but I should no longer hesitate), especially from the moral obligation we have towards it.

Many years ago, during my adolescence, when I was passing by Limth (Luma mountain), I saw some children playing in a meadow. Almost “out of habit” I was given to ask one who stood out among them: “Whose son did you marry?” – “Tahir Kolgjin’s”! – he replied as if with pride.

It seems that, even though they are fleeting and seem insignificant, they are never forgotten. And here, specifically: this case has remained indelible in my memory for the rest of my life. Of course, this phenomenon also has its explanation. I had heard this surname mentioned with respect many times by my father. He belonged to one of the most prominent families in those parts.

Many times later, I thought about the composition of this Catholic surname combined with the Muslim name, a phenomenon known in our mountains. I found this symbol of the grafting that history made on the autochthonous trunk of our nation interesting. It took a long time until I met Ahmeti again, only this time to never be separated again.

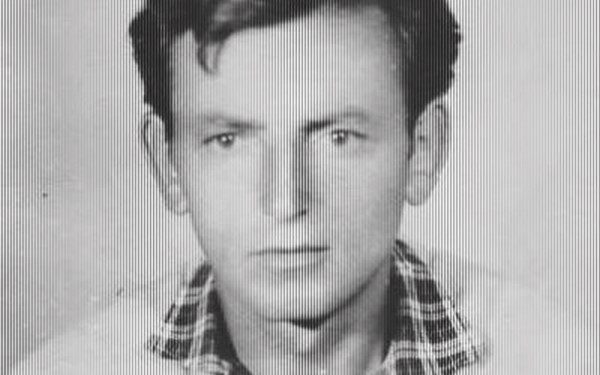

This happened in the Spaç camp. He was no longer the arrogant eight-year-old child I had met in the Luma mountains. He had already traveled a long in the ordeal of life. Since he was little he had suffered internment; in his early youth, he had been a political prisoner, then internment again, where he formed a family and where he had two children (a boy and a girl), then back in prison, where we were meeting together, which he had for the second time.

So now I had before me a thirty-five-year-old, with a body slightly below average, with shoulders raised, as if ready for some action, with a pale face of asceticism and with tired eyes that expressed the “resentment” of a biblical martyr. He had a voice with a special timbre, which you enjoy listening to, and also his laughter, which is the most sincere manifestation of a temperament.

But the dimensions of his greatness were in the spiritual world and, as is known, to penetrate there, a special optic is required. Ahmeti was sick and, nevertheless, he worked in the gallery of the Spaç mine. They did not report him, as they did with others. He was “targeted”, as “dangerous”, despite his exemplary correctness.

He was one of those who had the Socratic virtue of respect for the law, no matter how absurd it was. He was not a rebel, as were his other comrades in suffering, such as; Xhelal Koprencka and Fadil Kokomani; his resistance was of a different nature. He was stoic in the truest sense of the word. However, the organs of the dictatorship were very concerned by this “silence”. They provoked him in the lowest ways, but in vain.

How many times did he tell me how during the interrogation and on other occasions when they called him to put pressure on him, to “break him”, he remained calm, raising his eyes to the ceiling, as if he heard nothing. The insults did not reach his height. With this attitude, like an evangelical martyr, it seems as if he said: “Forgive me, Lord, for they know not what they do”!

Then they lost patience and…. the sick body could suffer some damage, but the soul, the soul where all its power was, became stronger. Like the Antaeus of mythology, who gained strength and became invincible every time he touched “mother earth”, so our hero gained that strength every time he relied on religious faith.

He had long since joined the Islamic Order, and precisely the “Rufai” sect, whose characteristic rite lies in spectacular self-sacrifice, in memory of the martyrs of the legendary battle of Karbala; a challenge to death, which for believers was considered polite. So he was not so afraid of death; this was also shown by his lack of sufficient care for his health. I have reprimanded him for this many times.

The “red quaestors” had already put him on the death lists, but the moment they were waiting for did not come; fate did not want a miracle. Finally, God, who was above everything for him, God wanted him to return first to the bosom of his exhausted family, where his sister, martyred for him, was waiting for him, as well as his wife with their two longed-for children, whom he had left orphans for a long time, alive.

Ahmeti left prison physically damaged, but spiritually hardened. The famous writer Stefan Zweig, in his brilliant analysis of the characters of world historical figures, tells us: “Prison can be the same for two people, but the effect can be the opposite.

Just as diamond and carbon, which are the same elements (they have the same chemical formula), so too two people are different, but can have the same fate; one may be finished when he leaves the galley, while the other may be coming to life at that very moment. The same fire that turns one into carbon turns the other into a diamond.” This undoubtedly happened with Ahmeti, our fellow sufferer.

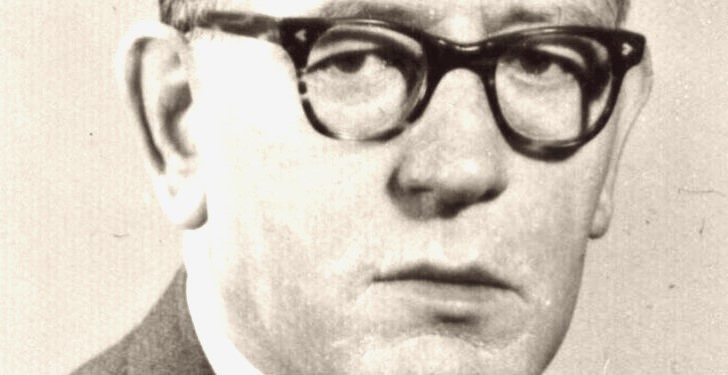

Many will have noticed that after prison, he radiated his spiritual qualities; then he, more than ever, displayed his intelligence, which reached mathematical precision, the education of an aristocratic delicacy, the self-taught culture, which surpasses in distance that of indoctrinated schools and, above this landscape of virtues, the bright sky of Islamic mysticism stretched.

But the presentation we made would be incorrect if, from his spiritual universe, we were to exclude his political ideal, his ardent patriotism that began with the love for his homeland, to that for martyred Kosovo, whose liberation he had the fortune to see recently.

Ahmeti loved the monarchical system, not as a mediocre and unprincipled fan, but as a philosopher, not as a petty egoist, but as a devout patriot. He was convinced that only the Monarchy could ensure national unity, without which there could be neither culture nor progress. History itself has provided an undeniable example, with the bright era of the reign of Zog I.

Our people, too, shaken by the anarchy that the dictatorship gave birth to, expressed their will in the referendum of 1997. He remained until his death incompatible with those politicians who put personal interest above the national one, therefore he opposed nationalism to them, as the only alternative to salvation. With death in his arms (Ahmet had undergone heart surgery), he took out all the internal treasure and put it at the service of the patriotic cause.

He gave the maximum of his intellectual and political skills. He was one of the organizers of the Legality Movement Party, after the overthrow of the communist dictatorship. At first he served as the party secretary, then as vice-chairman, and after a temporary withdrawal, he remained until the end, as a member of the PLL Steering Committee. In addition to political activity, Ahmeti also developed intellectual activity. He did not stop writing articles, fables, poems, etc.

At first he directed the newspaper “Atdheu”, then he wrote in various organs, such as; “Rilindja Demokratike”, “Liria”, “E Dhathta”, “Rimëkembja”, “Ora e Fjalës” etc. As a connoisseur of foreign languages, he studied and translated. He translated from English, the book by Professor Miftar Spahina; “About Kosovo”. In the original he wrote the introductory essay, in the surprising book for our culture; “Kodi Matematik i Koranit”, with dedication; “In memory of my father, Hafiz Tahir Kolgjini”.

As an inspirer of the “sublime”, he loved poetry. He writes: “Poetry sublimates our most delicate feelings”. And, with the instinct of the river, with deep pathos, he sings of “Gjallica kapuç bardhë” – “wearing green with snow pants”. I, the river myself, do not know if it can be sung more beautifully to that nature.

It is with this feeling that he writes the poem; “I long for Prizren”. He sang all of this with “Pain” and “Still Pain” (the titles of the two poems). Of course, a relatively short life, but dense in content, cannot be summarized in one article; for this, another measure is needed.

Congratulations will be given to the one who will undertake this initiative. In any case, one thing is certain: Ahmet Kolgjini’s life and work remain a model for future generations. And, if we think about the stagnation that this country is going through, we will be able to appreciate what a pearl its great example is. /Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue