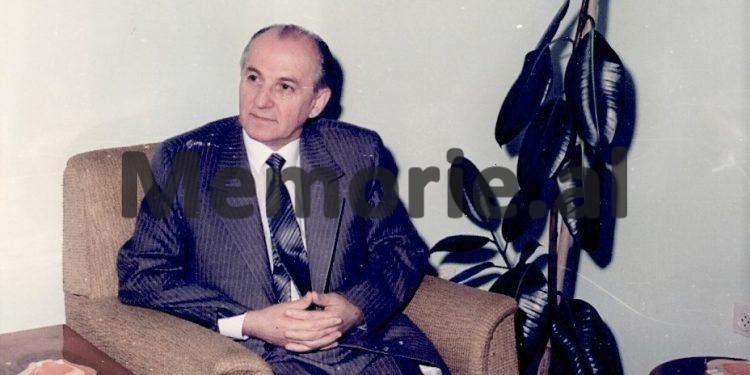

Memorie.al / Luan Kapllani are in his mid-sixties. Despite being on the threshold of old age, he still works, his hands on the steering wheel. But for him, being a driver has been something more than just an ordinary profession to feed his family. Because that steering wheel made him not only Ramiz Alia’s driver but also his companion, a close friend. For all those who hate Albanian communism, along with its former leaders, including the late Ramiz himself, Luan’s narrative has no reason to irritate them, as to him, he was a “dear man.” Ultimately, it happens that politics does not fully reflect the person who practices it, or their character. Thus, it can often portray them in a distorted way.

However, Luan Kapllani does not delve into such details belonging to psychological and social sciences. He recounts about Ramiz what he feels and what he experienced. Simply as a driver…!

How did it happen that you ended up as Ramiz Alia’s driver?

I was a driver at the Central Committee. I had been serving a head of the Education sector for the entire republic for about a year. And one day, my colleague, who was Ramiz’s driver and a bit elderly, spoke about me; there was a conviction that I was a sharp young man, suited to replace him. Meanwhile, Ramiz had left the choice in his hands, and he, Muherrem, chose me.

On the day you decided to take up the profession of a driver, had you ever imagined this?

No. I was an ordinary driver. I worked with a “Skoda.” But there was a time when work had slowed down, and I had mentioned to an acquaintance of mine who worked at the Committee that I was looking for a job there. And that is how I moved from the truck to the car. As for moving to Ramiz, it happened without any “friends” (influential connections), except for the high regard of my colleague.

But my father, when he found out I would become Ramiz Alia’s driver, told me not to go. He said I was better off where I was for the salary, that with the “Skoda” I had three empty seats where I could take a passenger, that whoever has been a driver for politics has ended up badly, etc., etc.

Did you feel nervous while driving, knowing you had “Comrade Ramiz” himself in the back?

Ramiz would take the nerves away; he made the experience in the car very easy, as he was very popular by nature. He understood when you might feel awkward or nervous. He had rare intuition, and in such cases, he would even sing a song.

What kind of vehicle was it?

A “Mercedes-Benz,” model 380 SEL. It was certainly a high-quality car, perhaps one of the best produced at that time.

The roads are full of surprises; have you faced any difficult or delicate situations? If yes, can you recall the one that has remained most vivid in your memory?

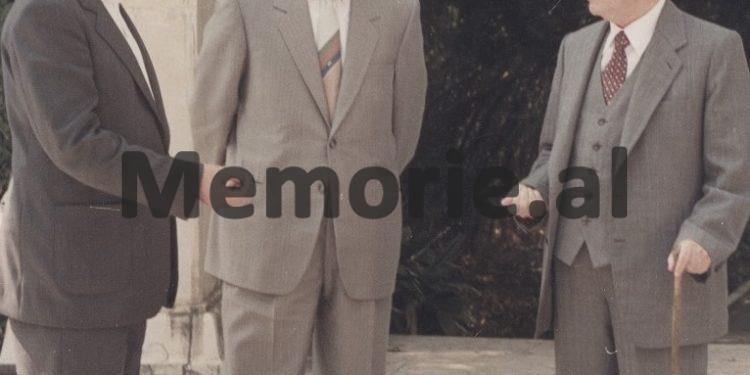

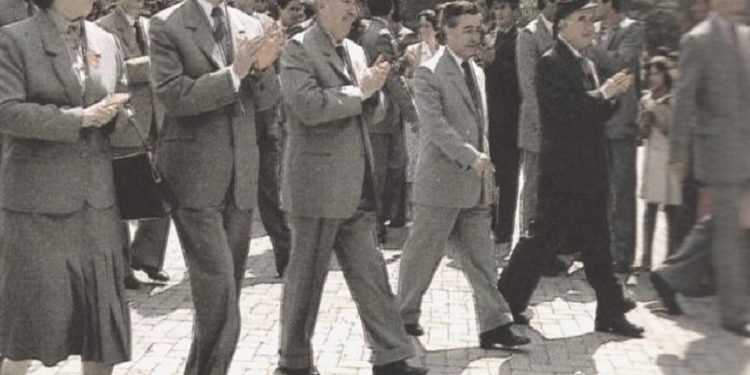

Surprises, I could say, started happening around the years ‘89-’90, a time when movements began that would later bring pluralism, and the situation was no longer as it was before—no longer as calm. I recall now a case when we went to Shkodra, after the killings of April 2, 1991. Dritëro Agolli was traveling with us. Before we set off, Ramiz told us: “In case someone there reacts with insults, slurs, or anything else, none of us should react.”

After we went to Shkodra, to the homes of the families of those killed, we headed to the “Migjeni” theater where a speech was held about Fishta. When we finished there and went outside to get into the car, about 20-30 people who were outside, as soon as they saw him, started insulting Ramiz. He did not get into the car but started walking toward them, while Dritëro was pulling him by his jacket:

“Where are you going?” he said.

“Go, leave me alone,” Ramiz replied and continued walking toward them.

They immediately retreated, while Ramiz greeted them and shook their hands. Thus, the situation calmed down. Meanwhile, the next day, on some of the front pages of the newspapers, it was written that Ramiz had been insulted and pelted with bricks and stones by the people of Shkodra.

Being a driver for a leader, naturally you get to know some aspects of his character, his “habits” as they are called. What were those of Ramiz that he displayed during the journey?

I think others, the people of that system, rarely had the character and culture of Ramiz. He was very cultured, very honest, very simple, and had a subtle sense of humor. His wife, Semiramis, the daughter of Professor Xhuvari, as well as the children and sons-in-law, were the same. He preferred to listen to music; he went out neither for hunting nor for fishing. He often played tennis and ping-pong. He did not smoke or drink alcohol at all, so he was a man of high morals, with a disciplined character and without vices.

You are telling me he was a man of much humor; do you remember any of his jokes or witticisms during the time you accompanied him?

I remember once as we were waiting for him to come down from the stairs of the house (residence) where he lived, and the guard at the guard booth had fallen asleep. He approached him, tapped on the glass, tap-tap tap-tap, and when he woke up startled, fearing he would be criticized, Ramiz said to him: “Careful, the minister is coming behind me!” (Following behind was Hekuran Isai, the Minister of Interior).

Another time, traffic lights had been installed there by the Ministry of Defense. Hekuran Isai was also in the car. We were returning from the Palace of Culture when the red light came on. I stopped. Hekuran said: “Go, go, these aren’t for us.” Immediately Ramiz reacted: “Hekuran is right, these aren’t for us, and they are for the car.”

Was he silent when traveling, or did he like to talk?

When we traveled, he was a person who loved conversation. And so, traveling with him was like traveling with an ordinary companion or friend. Thus, he had no complexes at all.

And what was the last trip with him?

I followed him many times after, even up to about two months before he was sentenced to prison. In fact, even when he had left office, and on the last day they moved him out of the residence after he resigned, on the day I took him home. I took him to his mother-in-law’s house, because he did not have a house. He stayed with his daughter and in-laws for two years. Although it may seem strange to you today, they took nothing from the state; they did not accept or allow it for themselves, because they were people of principles and ideals, and above all, they respected the law.

They paid for everything with their own money, from water, electricity, food, etc. The only thing he could get for free was the service, which came to the house. Everything was paid for with a receipt book; I paid them. There was even a young cook once who wasted food, and Ramiz replaced her with another, Feride, about whom he used to say: “How well Feride manages us, she keeps our costs low.”

To be the driver for the First Secretary at that time, or the President later, you must have had a good salary, I assume. How were you paid?

Ah, what can I tell you, nothing – a normal salary of seven thousand five hundred and fifty lek. In fact, if you compare it to the previous salary I had as a driver with the “Skoda,” it was smaller, because I used to get twelve thousand or thirteen thousand lek. Simply, when Enver died and Ramiz then became the First Secretary, I received a work suit once every two years. Memorie.al