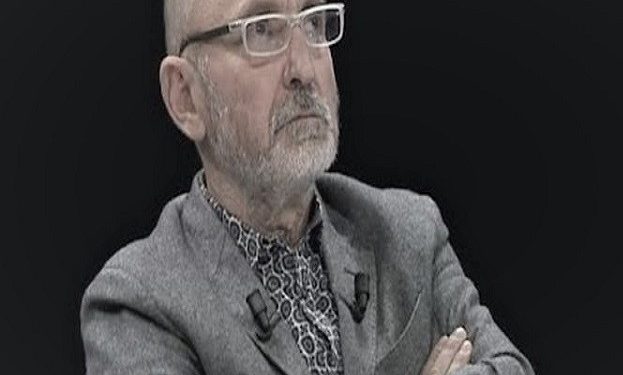

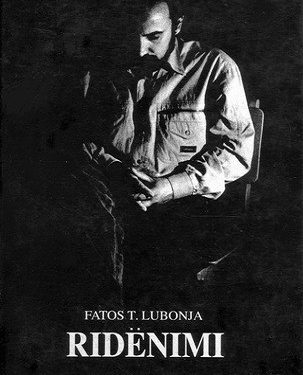

From Fatos Lubonja

The first part

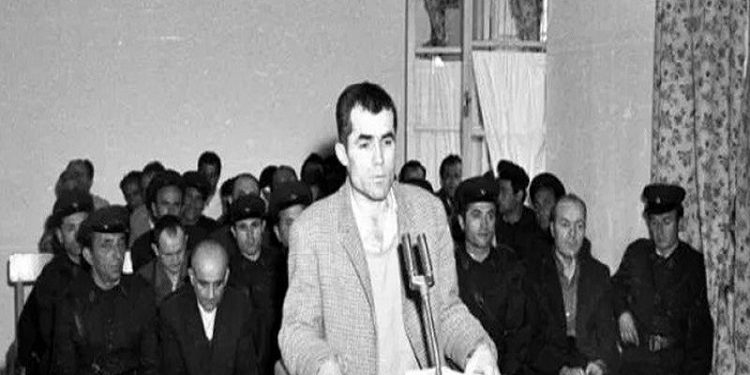

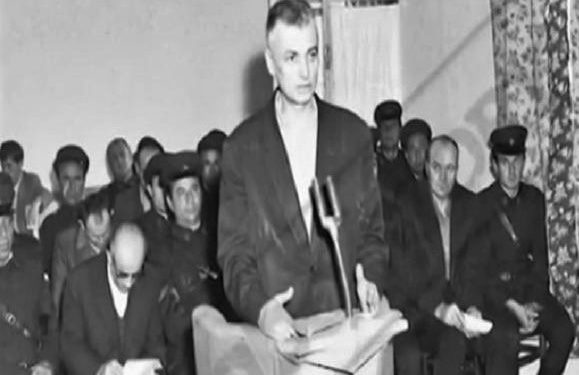

Memorie.al / Well-known writer, publicist, journalist and analyst. In 1975, when he had just completed his higher studies at the University of Tirana, at the Faculty of Natural Sciences (Physics department), he was arrested and sentenced by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, being accused of “agitation and propaganda, against popular power”, because during the inspection of the apartment, they found several diaries and notebooks with notes, where there were writings “against socialist realism and with hostile content”. Likewise, at that time his father, Todi Lubonja, (member of the Central Committee of PPSh and director of Albanian Radio-Television) was arrested, who was sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment and served his sentence in Burrel prison , until 1988, and then in exile, together with his wife Liri Lubonja and his other son, Agim. Meanwhile, Fatosi, while serving his sentence in Spaçi prison, in 1979, was arrested again, accused of being “part of a counter-revolutionary organization” which included Fadil Kokomani, Vangjel Lezho, Nuredin Skrapari, Beqir Alija, Vangjel Xhomo, Robert Vulkani, Dhimitër Stefa, Muho Bala, Petrit Orieti, etc., (where Kokomani and Lezho were sentenced to death and executed) and was re-sentenced again, spending nearly 17 years of his life in the camps and prisons of that regime. Fatos Lubonja, has been recognized by all his co-sufferers, former political prisoners, for his dignified attitude during the period of serving his sentence in camps and prisons, refusing to work in the Spaçi camp, which forced him the regime of that time, to lock him in Burrel prison, from where he was released in March of ’91, with the last contingent of political convicts, who were released from the camps and prisons of that regime. Since that time, Lubonja has been active in public life, not only as a publicist and writer, but also following with high intellectual passion, the political and social developments of the Albanian transition. Since 1994, together with a group of collaborators, he has published the cultural magazine “Perpjekja”, which has been appreciated both inside and outside Albania. For this, as well as for his intellectual commitment, he has been awarded many national and international prizes. After the 90s, Fatos Lubonja wrote the books: “The Great Flood”; “In the seventeenth year” and “Ridanimi”, etc., where some of them have been translated into other languages, abroad, while he is constantly present in the daily press, with various essays and articles, as well as an analyst of politics, etc., in the visual media. The writing that we have selected for publication is excerpted from his book, “Re-sentencing”, where it is about his re-sentence in the Spaçi camp.

FRAGMENT FROM THE BOOK “REVIVAL”

The word “shooting” was overused in prison camps and applied somewhat emotionally, since the stories that were told the most there were those of trials that had ended in death-shooting. But when I heard it in the courtroom, it sounded different. It appeared to me with the concreteness of an iron and murderous thing: I felt its terror penetrate to my core and shake my body.

I had heard dozens of stories about the court appearances of those for whom the prosecutor had sought the death penalty. In most cases, fainting and the expression of deep remorse prevailed, which had already begun with the break in the investigator. Then came the cases of those who had resisted all the tortures of the investigator, but were broken, after they were given the death penalty.

Fewer were the cases of broken ones in the investigator who, after hearing the death claim, denied guilt. And, finally, the rarest cases were the cases of those who had denied in the interrogator and continued to deny until the end.

I had always been intrigued by these stories because standing in the face of death seemed to me to be the greatest test a person can go through in life. But who’s proof, of spiritual strength or insensitivity?- I often asked myself since, not infrequently, the most delicate and sensitive ones had shown themselves to be the most fragile…!

Now that I was actually living one of these trials, these kinds of thoughts, like the word “shooting” heard in prisons, had no echo in my soul. Whatever Fadili or Vangjeli said, I would only be able to judge after everything was over.

* * *

The next day, the door of my cell was opened at around eight-thirty-nine in the morning…! “At last”! I said to myself. Now the irons fit me just for shape. When I entered the hall, I found at the end of it, the first curious and more than half of ours. There were also Fadili and Vangjeli. Soon we all did.

We were waiting in silence. The jury came in, but, surprisingly, it didn’t have the grace of delivering a verdict. The chairman, without much ceremony, turned to Fadili and said:

– Fadil Kokomani!

Fadili got up and remained waiting.

– The last word – added the chairman.

It seems that even Fadili did not expect this.

– I told him yesterday what I had to say – he answered.

– Okay, that was the defense. The jury tried the case and now, before making the decision, it wants the last word. What do you want from the court?

– I bear no moral, historical responsibility – were Fadili’s last words.

The chairman, as if this came out of the scheme, nevertheless said to Sadik: – Mark it!

– Xhafer Xhomo, – he then addressed Xhafa.

– I only ask for justice – Xhafa said flatly. It seemed to me a found word. – Gospel Lezho. – I demand justice in the measure of punishment – said Vangjeli, playing to the end the stone of hope.

– Beqir Alia.

– I believe that the jury will decide as fairly as possible.

– Fatos Lubonja.

– I want justice.

– Dimitar Stefa.

– I want justice.

– Muho Bala.

– I want justice.

– Petrit Orieti.

– I want justice.

– Robert Vulkani.

– Justice – said Roberti, with a voice more meek than the others.

– The jury retires to make the decision – said the chairman and came out in front of the five.

They took us and took us back to the cell.

* * *

After some two or three hours, the cell door was opened again. Again they put the irons on me, and again I took the same route, which I had taken so often during those nine days.

As I went down the stairs to the door of the tunnel bridge, I saw Xhafa being brought from below. This meeting was happening to me for the first time, because until that day, when they brought us to the courtroom, we never bumped into each other on the stairs.

I was surprised when I saw him with his eyes sideways up at a point on the ceiling, while his body was shaking as if he was getting winded. It seemed that without the support of the accompanying policeman, he could not climb those stairs.

When I entered the courtroom, I saw that it was packed with civilians, from those who had assisted in yesterday’s hearing. I had no worries about how much the court would give me, the 20 years requested by the prosecutor. I didn’t have any hope for Fadil either. The only concern was the hope that Vangjeli would not return alive.

At last the chief and those following behind him entered with a more solemn appearance. We all stood up.

The chairman began to read:

DECISION

IN THE NAME OF THE PEOPLE

The Supreme Court composed of:

Sofokli Kongo, CHAIRMAN – member of the Supreme Court with members: Met Rreli, Assistant Judge – member of the Supreme Court,

Luftulla Ceka, Assistant Judge – member of the Supreme Court, assisted by the Secretary, Sadik Memo, with the participation of the prosecutor, Skënder Breca, on May 10, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18, 1979 took into consideration in the court session behind closed doors criminal case No. 4 that belongs to the defendants:

- FADIL KOKOMANI, son of Hysen and Hatixha, born in 1933, born in Durrës, resident in Tirana, by social origin, middle-class citizen, by social status, clerk, journalist, with higher education, divorced, has one child, excluded from the Party, with Albanian nationality and citizenship, convicted twice for crimes against the state, serving his sentence in the Re-education Department No. 303 Spaç, arrested on 23.2.1979.

- VANGJEL LEZHO, son of Dhimitri and Emilija, born in 1932, born in Fier, resident in Tirana, by social origin, middle-class citizen, by social status, clerk, journalist, married, has one child, excluded from the Party, with nationality Albanian citizen, convicted twice for crimes against the state, serving his sentence in the Re-Education Ward No. 303 Spaç, arrested on 23.2.1979.

- XHAFERR XHOMO, son of Hasan and Myzafera, born in 1932, born in Leskovik, Kolonje, resident in Tirana, social origin rich peasant, bachelor, social status civil servant, zoo-veterinarian, highly educated, unmarried, unorganized, with Albanian nationality and citizenship, convicted once for crimes against the state, serving his sentence in the Re-Education Ward No. 303 Spaç, arrested on 23.2.1979.

- FATOS LUBONJA, son of Tod and Liria, born in 1951, born and resident in Tirana, social origin senior civil servant, social status civil servant, highly educated, married, has two children, unorganized, with nationality Albanian citizen, convicted once for agitation and propaganda against the popular government, serving his sentence in the Re-education Department No. 303 Spaç, arrested on 23.2.1979.

- BEQIR ALIA, son of Ali and Merjeme, born in 1927, born in Shkodër, resident in Fier, social origin middle-class merchant, social status civil servant, geological engineer, highly educated, married, with two children, expelled from the Party, with Albanian nationality and citizenship, convicted once for crimes against the state, serving the sentence in the Reeducation Department No. 303 Spaç, arrested on 23.2.1979.

- MUHO BALA, the son of Adem and Bedria, born in 1932, born and resident in the village of Golem in the district of Shkodra, with social origins as a poor peasant, with social status as a worker, with incomplete secondary education, unmarried, has a child, expelled from the Party, convicted once for crimes against the state, serving his sentence in the Re-Education Ward No. 303 Spaç, arrested on 23.2.1979.

- DHIMITIR STEFA, son of Nikola and Vasillo, born in 1934, born in the village of Grazhdan in the district of Saranda, resident in Fier, by social origin a poor peasant, by social status civil servant, geological engineer, with higher education, unmarried, without children, unorganized, of Greek nationality, with Albanian citizenship, convicted once for crimes against the state, arrested on 23.2.1979, serving his sentence in the Department of Reeducation No. 303 Spac.

- NUREDIN SKRAPARI, son of Nuredin and Xhevria, born in 1943, born in Lushnje, resident of Stalin City, by social origin a rich peasant, classified as a kulak, social status civil servant, geological engineer, with higher education, unorganized, with Albanian nationality and citizenship, convicted once for crimes against the state, serving his sentence in the Reeducation Department No. 30 Spaç, arrested on 23.2.1979.

- ROBERT VULLKANI, son of Sotiri and Merop, born in 1934, born and resident in Tirana, social origin worker, social status civil servant, journalist, highly educated, divorced, has one child, expelled from the Party, with Albanian nationality and citizenship, convicted once for crimes against the state, serving the sentence in the Department of Reeducation No. 303 Spaç, arrested on 23.2.1979.

- PETRIT ORIETI, the son of Fuati and Darovija, born in 1941, born in the village of Gusmar in Tepelena, resident in Tirana, of social origin, a poor peasant, with a social status of a worker, with an education of two middle classes, unmarried, has no child, unorganized, with Albanian nationality and citizenship, convicted ten times for theft of socialist, civic property, unworthy behavior in society and once for agitation and propaganda against the state, serving the sentence in the Re-Education Department No. 303 Spaç, arrested on 23.2.1979.

Next, he began to count the charges and punishments that the prosecutor had requested for us, as well as what we had requested in the last word. They were things that had been repeated so much that the words passed me by without leaving any trace. However, I was curious to see how the court’s analysis would differ from the prosecutor’s because, according to custom, it should be a little more lenient. But the chairman continued to read:

… From the examined evidence it was fully proven that the defendants…being old enemies of the party and the state, politically degenerate people…grouped in a counter-revolutionary organization, which aimed to overthrow the people’s power … Its organizers, inspirers and leaders were the defendants Fadil Kokomani and Vangjel Lezho.

… Both these raging enemies…

My hope that Vangjeli could be separated from Fadili was fading from turn to turn. Their names were always together, never even apart, as the prosecutor had sometimes decided, singling out Fadil as the main inspirer.

When half of the reading of the decision was over, I no longer had any hope for Vangjeli. The text of the decision was a copy of the indictment. Even the Gospel was lost. There was nothing more to hear. However, when he got to the word “DECIDE”, I again called to his attention.

… To declare the defendants Fadil Kokomani, Vangjel Lezho guilty for the crime of creating an organization… to declare the other defendants guilty for participating in an organization… on the basis of the relevant provisions of the Criminal Code, they are sentenced as follows .

Fadil Kokomani…shot to death…

Vangjel Lezho…shot to death.

Then our sentences that started with 23 years for Xhafa and ended with 16 years for Robert.

The chairman rested both hands on the table and glanced at us. It seemed as if something had been left unsaid. He felt like that for a moment and then ran away to the head of the jury without speaking.

The police quickly began taking us one by one back to our cells. They started from the last row. We would leave Fadil and Vangjeli there, since, since yesterday, they left them both for the end.

The first one they took was Petrit, who was in the last row. Leaving the door, he turned his head to Fadili and Vangjeli and said:

– Fadil, Vangjel, don’t be upset!

This spoken in that grave silence and horror, sounded like a challenge.

I had a few moments to stay there with Fadil and Vangjeli.

The first thing I did was eyeball the two. Vangjeli had remained as if frozen and contracted all over, with a blackened face to the point of horror. He glared at me with unusual strength and concentration. There was in those eyes and in the whole appearance a surprise mixed with an indescribable fear, there was also disappointment for the hope I had given him that he might remain alive.

Then he looked at Fadili. To my surprise, Fadili had a very light face, lightened by the tensions and nightmares of death. He looked eye to eye with Vangjeli and smiled at him. Vangjeli did not react to her at all.

Meanwhile, the police were coming to take me. Vangeli looked back at me. We were very close to each other and face to face. He once again poked my eyes in the eye sockets. This time, the persistence of his gaze in my eyes seemed to me that he wanted to convey to me not only the horror and fear of death, but also the surprise and pain he felt.

It seemed to me something more. As if through that look, he was in a hurry to convey to me the trust for the girl and for the woman, the trust that we would not forget them on the day of freedom, about which we had talked so much and not only that. It seemed to me that through the gates of his eyes, he wanted to pour his very life into me.

I turned my head to Fadili once more. His face remained calm, without any sign of terror. He smiled lovingly at Vangjeli again.

That smile and that clarity remained an enigma to me. It seemed to me that she also expressed some relief from the fear of not going to the grave without his friend, as if he was happy that, at least, he would not experience the horror of death alone.

But along with the monstrous human selfishness, in that expression, it was also felt that he loved Vangjeli in those moments more than ever, as if he looked at him with compassion and love like a little brother, a little scared before the dark goal they were heading towards; as if he felt a responsibility to help her finish the path they had started together and which had now reached its most difficult stage.

Ten days after the decision, on a Monday morning, they opened the door and told me to take what I had in the dresser. I was finally escaping from that cell that had crushed me so much. Memorie.al

The next issue follows