By Zyhdi Morava

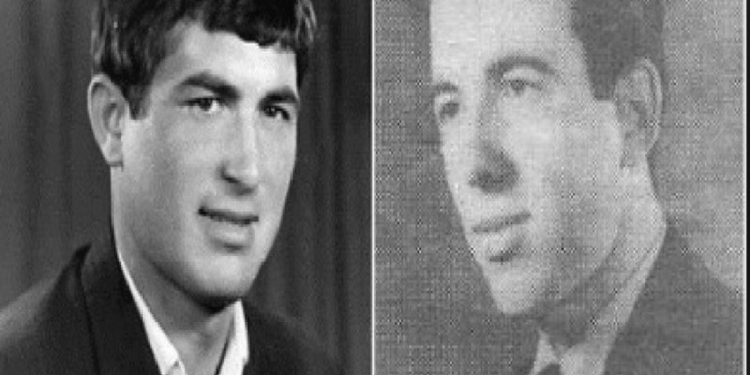

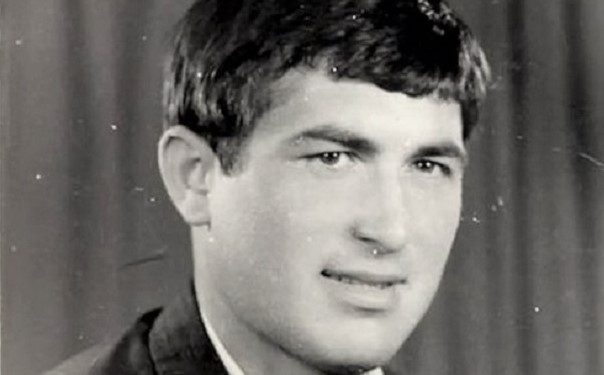

Memorie.al / Zyhdi Morava were born in the village of Grace in Devolli, on March 14, 1946. Although for biographical reasons he worked as a laborer, in his youth he found time to deal with writing and literature, together with a group friends known as young writers, which included: Bedri Myftari, Roland Gjoza, Ahmet Golemi, Kosta Dhamo, etc. At the beginning of the 70s, most of this group of young people were criticized and beaten for “foreign and liberal appearances” in their works, and for this reason, Zyhdi Morava was first exiled from Tirana, being sent as an agricultural worker to the village of Yrshek, on the outskirts of the capital. After a while, (in 1978), for the same reasons, he was arrested and sentenced to 8 years in prison, which he served in the Spaçi camp. After the overthrow of the communist regime, in addition to literary creativity, Morava engaged in the creation of independent trade unions and for several years he worked as a journalist and editor of the newspaper “Syndicalisti”. Likewise, after 1991, he published several books both in poetry and prose, and for some time he was the chairman of the League of Writers and Artists of Albania. The part that we are publishing in this article is taken from his memoirs, where he describes in a literary way the period of arrest of two poets originating from the village of Bërzeshte i Librazhdi, Genc Leka and Vilson Blloshmi, as well as the testimonies of his co-sufferer, Bedri Blloshmi, regarding the death sentence and shooting of Genci and Vilson, after they were accused of being “enemies of the people”!

THE SHROUD OF THE MOON

On the same day that they gave us the death sentence, each of us in our own cell, we were tied hands and feet and a spacesuit was placed on our heads. All these measures were taken so that we, overcome by despair, would not kill ourselves by hitting the wall with our heads or in some other way. And while we were sitting like that, huddled and bound, our mother and Genci’s mother, were rolling at the doors of the Court of Appeal, at that of the Supreme Court and finally, with almost extinguished hopes, like two rivers flowing under the ground of dryly, they stopped the flow at the large and heavy gate, which was guarded by armed soldiers of the Presidium of the People’s Assembly. And at the feet of the “gods” who had our lives in their hands, they threw their prayers from the mother, cried, mourned, asked for our lives to be spared.

Lord, they prayed in silence, great and loving God, fill THESE minds, to spare the lives of our sons.

And the answer came. But not from God. It came from THEM.

– “Your sons are dangerous enemies of the Party and the state. Those who wanted our death will be punished by death. Yes, our Party has a big heart. The Presidium of the People’s Assembly decided to spare Bedri Blloshmi’s life, to serve 25 years in prison.

When the death sentence was finally communicated to me, I remember that I felt the taste of it in my mouth, something between the taste of soil and grave. Again I found strength to ask:

– What about Bedriu?

– They took away death. Even worse. He will die in prison. He was sentenced to 25 years.

And they continued:

– Are you frowning?

Only then did I realize that I had smiled. Smile that my life gave me brother. Who has life, has hope.

They took us that same night. Better to say, at midnight. At first they took off my space suit. I turned my head as if to stretch my tired neck. Then they took off my chains and put handcuffs on my hands that were tied behind me. I saw Genci in the prison corridor. She was almost as weak as she was. His tearful eyes looked at me as if they were asking me for something, as if they were looking for salvation in me. They put on our shoes. I glanced at Bedri’s dungeon. He didn’t feel alive. Was he sleeping? How did he sleep that night, how…?! The moment they took us by the arms, Genci first and me after, I called out:

– Goodbye friends! Brother, goodbye!

And my heart sank. I did not listen to his voice for the last time, my brother, my beloved, the good, the brave, the little one. From the surrounding cells, many voices answered me:

– Courage, Wilson!

And unrestrained, I screamed:

– Bedriiii…!

But Bedriu was silent. Why so, oh God, why? What happened to him?

(That night, Bedriu told me when we were in Spaç, that night I knew they would be taken. That’s why I had decided not to sleep. At least to say the last goodbye to Vili, the brother I loved so much. Yes I didn’t have the strength to resist. In the dinner plate, they had thrown sleeping pills, even in large doses. In the morning, when they were taking me out to the bathroom, trembling, I glanced at the place where my shoes should have been. Vilit. They were missing. They had run away with death. I fainted).

They put us in a car-jail. Mobile prison. Hermetically sealed. Genci and I were shoulder to shoulder. It trembled. Weak and scared I was in pain. I wanted to give him courage, but what should I say? Can a person be comforted on the verge of death? I occasionally felt him lean against me. This happened every time the car took a turn. I felt the warmth of that distraught body; I felt his life, that life that, after a while, would be extinguished like extinguishing a lighted match when we blow out after lighting a cigarette. Mine too. Why so? What bad did we do?

The auto-jail stopped. We were taken down by supporters. The first thing that caught my eye was Shkumbini. With a silvery glow stolen from the moon, it ran somewhat nervously and contemptuously, creating luminous scales where its flow met underwater rocks.

It was a summer night with a full moon, the night of July 17, 1977. I have never seen the moon more beautiful and brighter than that night. A wooden bridge connected the banks of the river. We passed over that bridge under which the Shkumbini flowed with a slight moan, as if it felt sorry for our young lives that were going to die out a little further.

I wanted to give him a gift for those beautiful days he gave me in summer, when I bathed in its cold waters, in autumn with the pale reflections of the trees in its stream, and in spring with the leafy green of the willows and grown turnips next to him. What should I give him? I had nothing.

In front of me are policemen from the firing squad. Behind me came Genci, silent as the moonlight. Behind him again policemen from the firing squad. I stopped opening just for a moment and very quickly took one shoe off my foot, which I threw unnoticed into the somewhat moaning and complaining flow of Shkumbin. From this, I was very happy. What else could I give you, my old friend, what else could I give you?

We left the bridge and the thick trees to climb a steep ascent, a newly opened path, among the bushes of mares, laurels and other wild trees from which, after the heat of the day, the aroma of the moist leaves of wild flowers bloomed under the bushes, where the sun could see them.

The barista with difficulty, hunched over, quieter than death. It was not easy for me either. In addition to the common throbbing with Genci, I had a bare foot. I was torn from the bushes and torn from the stones. But what did it matter? Aren’t we going to die soon?

They ordered us to stop somewhere, quite far from the river that flowed along the national road, at the stream of Firari. They placed us on the edge of a not so deep pit, which they seemed to have dug that very day. With their backs to her and facing the policemen who lined up with guns ready. The barrels of the rifles flashed in the moonlight and looked like snakes directed at us, cold and venomous.

– If a miracle happens! Genci whispered to me.

I looked at him softly and smiled.

– Squad, weapons ready!

The muzzles of the rifles were pointed at us like the eyes of monsters. How much and how beautifully that silent moon shone! What was the moon doing those moments? What about Diana? Could it be that she felt that I was leaving her for good and was pulling out her black hair and wet it in a low voice in her room, in our room?

– Squad, ready to fire!

What was that strange calm? How a bird not sing to rejoice at the shining moon did, how did a bird not crow?

Why didn’t the leaves of the bushes rustle? Does death come so silently?

We were approached by the prosecutor, the one who had sought our death with a strong desire and special persistence. He stopped next to Genci. He said:

– The last wish.

Genci raised his squinting eyes and answered in a broken voice:

– “I would like to entrust my little son to someone, for whom my soul will not be comfortable, but I cannot ask this of you, dirty and cursed murderer.”

I have never seen him braver. The prosecutor, as if deaf, came next to me and repeated in the same tone:

– Last wish.

– “You deserters, I told you, you deserters, who do not understand that you are shorter-lived than us, that you will kill us in a little while…”!

The prosecutor, always deaf even to my words, quietly left the space created between us and the firing squad, as if leaving the café. And cruelly came the order:

– Fire!

Which brought bullets to our bodies before the bullets? And we burst into the pit, as close as we had been in life, in spirit, and in dreams. By chance my hand touched Genci’s. She was shaking as if she had a cold. He sighed a little and was silent. The moonlight fell on my face. I have never seen it so abundant and so bright. A crack was heard. That shadow was the prosecutor who cast over Genci’s lifeless body.

I don’t know if he or the moon moved, but in its light I saw Diana walking barefoot on the shores of Shkumbin, her hair braided to her knees, calling my name. Beyond, at the big Bërzeshte maple tree, my mother was wiping with the corner of her headscarf, her eyes were saying something to the moonlight, which after another crack, turned into a shroud, wrapped me gently and threw me far, far away , in a place of no return that was called ‘SAHARA’, where the desert desert remained desert…! Memorie.al