By Reshat KRIPA

Part Fourteen

Memorie.al / Arbër was standing in his corner in the hall, awaiting the arrival of the plane that would take him to another world, and meditating. He meditated and dreamed of the road full of thistles and thorns through which his life had passed. He recalled the worries that had accompanied him for years. He had many passions. He wanted to become a lawyer, journalist, doctor, engineer, artist, writer, or whatever else might be possible. But fate had condemned him to reach none of the peaks he dreamed of. He encountered disappointment at every step of his life.

Continued from the previous issue

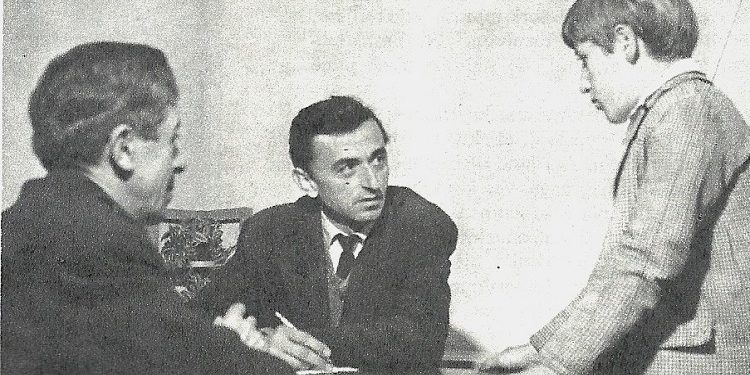

The democratic government approved a law that gave former Political Persecutees and Prisoners the right to pursue higher education without taking a preliminary entrance exam, as was usually done. The implementation of this law fell to the office where Arbër was director, but with the condition that it also received the approval of the Association of former Political Persecutees. Arbër was sitting in his office, reading a document. There was a knock on the door:

“Come in!” Arbër spoke.

Ibrahimi entered the office and stood there as if frozen.

“Where have you been, Ibrahimi, showing up so suddenly?” Arbër said in an ironic tone.

Ibrahimi did not speak.

“Speak, why are you silent?” Arbër continued. “Where did that lecturing of yours go, when you whistled before the organs of the State Security?”

According to the accounts of some other fellow prisoners, Ibrahimi had testified against them in court as well. He hadn’t stopped just with Arbër’s case. Becoming a witness had become his second profession.

“Forgive me,” he finally spoke. “I was forced to do it.”

“And for the others, were you forced?” Arbër interrupted him. “Enough with the nonsense, tell me why you came?”

“I want to continue my higher studies.”

“First, go get the approval of the Association of former Political Persecutees and Prisoners.”

“I went, and they didn’t accept me.”

“Then what do you want? Should I forgive you?”

“Precisely.”

“I cannot. Continue your life. Ask your conscience, and if it answers you, it means you are truly repentant. But this takes time and depends on your actions. Only then do you have the right to ask for something.”

Ibrahimi left with his head bowed.

Meanwhile, Arbër was continuing his second year of Law School via correspondence. He was, as always, at the top of the excellent student rankings. Blerina had been appointed director of the school where she graduated. They were a model family. God had also blessed them with a little boy named Sokol, after his grandfather. He had just turned three.

One evening, they were talking about current affairs. Arbër had been somewhat preoccupied for days. He had searched through the numerous documents his mother had left him, hoping to find a phone number for his grandfather, who was in America, but it was useless. His mother hadn’t corresponded with him for over thirty years. Except for the first ten years or so, when they occasionally exchanged a phone conversation, contact had been cut off. A secret order from the communist government had severed relations with relatives living abroad. Thus, his mother naturally couldn’t have a number.

Suddenly, the phone rang. Arbër picked up the receiver.

“Hello!”

A trembling voice spoke: “I am your grandfather; I am speaking to you from the United States.”

Arbër was shaken.

“Grandfather?”

He remained silent for a few minutes.

“I told you I am your grandfather, Shkëlzen,” the voice on the receiver repeated.

“Forgive me, grandpa, forgive me!” Arbër began to speak. “I didn’t expect this. I’ve been trying to contact you for a long time, but I couldn’t. I am your grandson, Arbër. How are you, grandpa?”

“Well, my son, well. The conversation I’m having with you, your voice, is giving me unimaginable pleasure. I’ve been waiting for this day for years, and finally, it has come. May you be happy, my son!”

The conversation continued for a long time. The grandfather told Arbër how he managed to connect with him. Through the escapees who had gone to America, he had learned about the fate of his son-in-law, Sokol, about Afërdita’s stand, about her son, his engagement to Blerina…! After the democratic changes, he had met other Albanians who had gone there and asked them. Finally, he had inquired at the Albanian Embassy in Washington and had not left them until they found Arbër’s phone number. In the end, he had told him that despite his great age, almost ninety, he would come to Albania. He wanted to see his beloved homeland and his dear people one more time. It was longing that drove him.

The day of arrival came. Arbër, Blerina, and little Sokol went to the airport, located in the northwest of the capital. Along with them was one of Arbër’s fellow prisoners, who had been a friend and classmate of Shkëlzen’s. His name was Dritan. Arbër wondered if he would be able to recognize his grandfather. In the photographs his mother had left him, he was a young man, but now he would see an elderly man. He had prepared a sign, decorated with a bunch of flowers and inscribed with: “Welcome Grandpa Shkëlzen, Welcome!”

The plane arrived. The impatience was great. Minutes passed, and the grandfather was nowhere to be seen. Finally, the passengers began to disembark. Among them, he distinguished a man dressed in a chic black suit, with a tie and a fedora (republicë) on his head.

“That must be him,” Arbër thought.

He stepped forward, raised the sign, and cried: “Grandpa!”

The grandfather paused, looked at Arbër, opened his arms, and said: “Come, my son, come embrace your grandfather!”

They jumped into each other’s arms. They couldn’t pull away. He also embraced Blerina and took little Sokol in his arms, lifting him high, and said: “You are the future of the homeland!”

“And won’t you meet with me?” asked Dritan, who was standing nearby. Shkëlzen looked at him from head to toe. They were both the same age.

“Don’t you recognize me?” Dritan asked again.

“If my memory has not failed, you are my friend, Dritan, you are my classmate,” Shkëlzen said in a voice trembling with emotion.

They hugged. He never thought he would meet his old friend on the day of his arrival in Albania.

They left. Throughout the journey, the conversation did not stop. Two days later, Arbër hosted a lunch in honor of his grandfather. Known personalities of the city participated. Shkëlzen had completed his higher studies and had managed to become president of an electronic company. Thus, the conversation was of a high level.

Arbër took his regular leave and toured almost all of Albania with his grandfather. They also visited the cemetery, where he placed wreaths of flowers. The grandfather was thrilled. He proposed to his grandson that they apply for family reunification so he could obtain American citizenship. Arbër accepted.

The grandfather went to the United States Embassy and discussed the matter. They showed him the documents they needed to fill out. The formalities were completed. The Embassy announced that Arbër had to travel with his family to the United States to be equipped with a “green card.”

A month later, the grandfather, the grandson, and his family set off for the United States of America. Arbër stayed for a month, just long enough to get the “green card.” He couldn’t stay longer. The homeland was calling him. There were the graves of his parents, his job, and his friends – in short, his life.

Three more years passed. The country was plunged into chaos from which it was difficult to escape. Entire crowds of people were seen taking to the streets of the cities, shouting and screaming. In their faces, one saw nothing but a bestial savagery.

Cries for overthrow were heard. Burning and destruction were seen everywhere. Crowds of people were forced to abandon their homeland, some by boat, some by car, and some on foot. The murders of people serving in state organs were not few, and, surprisingly, the shouts heard after them were:

“The government killed them! The government killed them!”

Arbër watched and meditated. Why? Why would the government kill its own people? Why this savagery in the faces of the crowd? Who caused it? He recalled the thousands killed, the tens of thousands imprisoned and interned, and he had never seen such hatred, such savagery in them.

How was it possible that only five years after the establishment of democratic power, the people would rise up against it?! People whispered that the loss of money they had deposited in some phantom firms had caused this revolt. But then why weren’t they rising up against these firms but attacking the government?

News circulated in the city. A grand demonstration would take place in its main square. Exalted crowds rushed toward the square. It was completely full, as never before. Arbër stood in one corner of it. He had gone to see what would happen.

The rally began. Resuli appeared on the podium and started speaking. He spoke and spoke, pouring out endless vitriol against the government. Suddenly, the democrat had returned to his origins. Arbër couldn’t listen anymore. He covered his ears with his hands.

Resuli spoke while the days spent in the Security cells flashed before Arbër’s eyes. The events passed in the forced labor camps, and above all, the end of his friend Xhavit. The first days of the great overthrow came to mind. He hadn’t seen the savagery then in the faces of its participants that was now seen in the faces of the rebels.

Recalling this scene, Arbër asked:

“Are there murderers among us? Who are they?”

The answer was definitive: “Yes.” They were the investigators and former employees of the State Security. They were the heartless prosecutors and judges who carried hundreds and thousands of people killed or died in prisons on their consciences, whose graves were not even known. They were the spies of Mersini’s type, waiting for the opportunity to bury other people again. This was because justice had not acted!

With the overthrow of the dictator’s monument, which had happened six years earlier, they thought they had overthrown the system it represented, but in reality, they had only overthrown the bronze of that monument, and its spirit they had left free to roam the country and prepare other catastrophes like the one happening those days.

But there was another kind of murderer, more dangerous and more criminal than the first! They were the two-faced ones, who, although dressed in the garb of a democrat, were waiting for the next day to stab the fragile democracy being built in the back! They could be found everywhere. They could be found in the government, in parliament, in the justice system, in political parties, in associations. Instead of deserved punishment, they now roamed freely, pouring poison into people’s consciences. One of these was Resuli.

They strained their voices, shouting: “We are innocent! The overthrown system was to blame!”

As if it was not for these unprincipled people who had kept that system alive for almost half a century. And Arbër asked himself:

“Who then was the culprit for all this disaster that had covered the country?! Who was the culprit? Could it be us, who paid with our lives?!”

He recalled a sentence from Giovanni Sartori, who wrote in his book, “The Theory of Democracy Revisited”: “People who have never known dictatorship and tyranny find it easy to indulge in rhetoric about freedom, completely forgetting the simple and terrible reality of genuine oppression, where it truly exists!”

At this time, the announcement from the American Embassy was published, requesting the departure of all its citizens from Albania. It announced that all American citizens in Albania should gather in the capital, as it would provide airplanes for their departure.

A phone call rang in Arbër’s house. It was his grandfather, who had heard the embassy’s news and was informing him to leave with them. He had also discussed this with the American Ambassador to Albania. Arbër decided. He would leave. A day earlier, he went to the cemetery and bowed before the graves.

“Father, Mother, forgive me! I am abandoning you! I am abandoning the homeland too! But I am forced to. I promise I will return again.”

He met Petrit and entrusted the graves to his care. He promised he would keep his promise.

He set off for the airport.

The loudspeaker spoke in Albanian and English:

“All passengers on the Tirana – New York line, please board the plane.”

Arbër hesitated.

“Arbër, why are you thinking?” Blerina asked.

“At this moment, my whole life, yours, and our son’s flashes before my eyes, and I don’t know if we have chosen the right path to leave…?”

“Why this hesitation?”

“Because of the state in which we are abandoning the homeland, when its reins are being taken over by the very people who were its gravediggers, while those who fought and sacrificed for this day have been left at the mercy of those who, until yesterday, clamored for the dictator and whose hands were calloused from cheering for him!

Someone might tell me that I should stay to confront them, but I see it is useless. Wolves do not let the sheep graze freely, and my eyes hurt when I see wolves leading the state!”

The three of them took their assigned seats. It didn’t take long for the plane to depart.

“Goodbye, or rather, farewell, my dear homeland!” said Arbër.

“Farewell! One day we will return again,” Blerina replied. But will they return? Memorie.al