By Adelina Gina

The third part

-“I cried for you like dead, I waited for you like alive”-

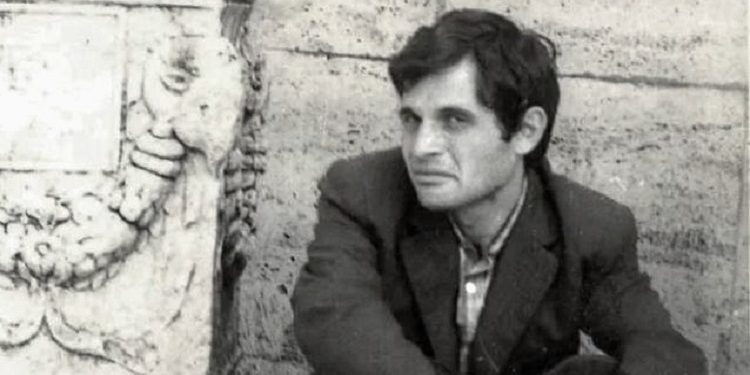

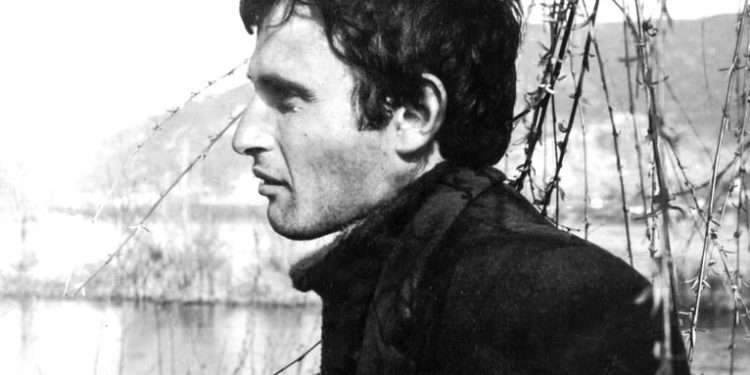

Memorie.al / Rescue Gina, graduated in Journalism at the University of Tirana, in 1974, playwright, screenwriter and librettist, in the early 70s, thanks to his extraordinary talent, his work, works and creativity, “shocked” the artistic institutions of Tirana, as; The People’s Theatre, the Opera and Ballet Theatre, the High Institute of Arts and the Albanian Radio-Television. He was one of the most sought-after chiefs and senior leaders of these institutions. In the time period 1971-1974, he left his mark, having collaborated closely with some of the most famous names of that time, such as: Mihallaq Luarasi, Kujtim Spahivogli, Pirro Mani, Mario Ashiku, Zhani Ciko, Nikolla Zoraqi and director Mevlan Shanaj and operator Pali Kuke. But the traces he left in these cultural and artistic institutions were unfortunately lost in the official silence of the communist regime?! In August 1974, Shpëtim Gina, lost his life in unexplained circumstances, drowning in two feet of water, in the river Drojë of Mamurras, (where he was performing the military choir together with other students), two days before, he had put a lightning sheet to the Chief of the General Staff of the Army! Was it really an accidental death, or was Shpëtim Gina eliminated by the State Security?! Why his “friend” who was with him until the last moments, declares that; “The body that was taken in the ambulance, wasn’t it Rescue?! Or the doctor of the military department of students, Mark N., who says: “We immediately went to the scene, but we did not find the body of Spetimi”?! And his family, why insists that; “They didn’t allow us to open the coffin before the burial when they brought it home and years later, we opened the grave in ‘Stalin City’, to bring it to Tirana, where we had moved as a family, those bones were not of Salvation, as they were missing. ..”?! Many questions, which have not yet received an answer! His sister, Adelina Gina graduated in journalism in the late 60s, in a book of hers entitled; ‘Where did you take Salvation’, published in the USA.

Continues from last issue

I was at work. The newspaper where I worked is in the Ministry of Education and Culture. The district court is located near it. It is a building outdated by time. Ordinary trials are usually held there. There are always people who spend hours in court sessions, there are also petty thieves, prostitutes. The audience was like that the day Sadija and I went to court. She knew that on that day, the trial of two artists, Mihallaq Luarasi and Minush Jero, would take place. There were some ordinary guys in the hall, no artists at all. We sat down, behind us a woman was sobbing, she was the wife of Minushi, the playwright. The defendants, especially Mihallaqi, were yellow wax. Irakliu was the chairman, with the seal of ignorance on his face. The prosecutor, a blond, appeared to be an art connoisseur. He didn’t have a lawyer, because in a dictatorship, absurd things happen.

A few years ago, lawyers were removed. Mihallaq Luarasi, was accused of staging Minushi’s drama; “Brown Stains”, a revisionist work, and that he had browsed foreign literature, had seen revisionist scenography. He had studied in Hungary. To prove this, they brought as a witness the director of the

University Library, who was trembling. When Mihallaqi spoke, he said, among other things: “I know a talented young man who does not read in foreign languages, yet his work is of a foreign, expressionist current.” He tried to say the name, but the prosecutor stopped him: “We don’t need names.”

The trial continued with Minush Jeron and then the witnesses called. The session was adjourned. He cannot enter the next day. The news had spread, all the artists had filled the hall and the square in front of the court. We met at home, for the new year. I told him the incident. He wanted to defend you with that thesis when he talked about you. They didn’t let him reveal your name there, but he said it to the investigator. Salvation was silent. The Middle Ages, that was the Middle Ages. And as if to remove this evil, he told me: “I have done a lot of work with Venema”. It was another drama of his, which remained unfinished. In short, the drama was this:

From different countries of the world, specialists from different fields gather to experiment a socialist revolution on an island. During the course of events, the announcer announces that the steamer they were traveling on sank. The symbolism is clear, the socialist revolution failed. “Do you really believe that socialism will fail”? I asked him in surprise (it was 1973). “Yes, – he said. – Don’t you see what violence there is? And there is just as much economic poverty”! I was silent. To be honest, I didn’t think you would collapse, even after eighteen years, like it happened to us.

Shpetimi graduated from the faculty and started working in Radio-Television, in the editorial office of culture, as a screenwriter. He was enthusiastic, “we will make television films, feature films”. Salvation began to write scripts, collaborate with the director. The director was a young man, at that time he was married to a poetess, he was kind to us. Even when the girl was born, Salvation found her name. One night we took some food with us and went to his house. He has to cross three bridges; he had his house on the third.

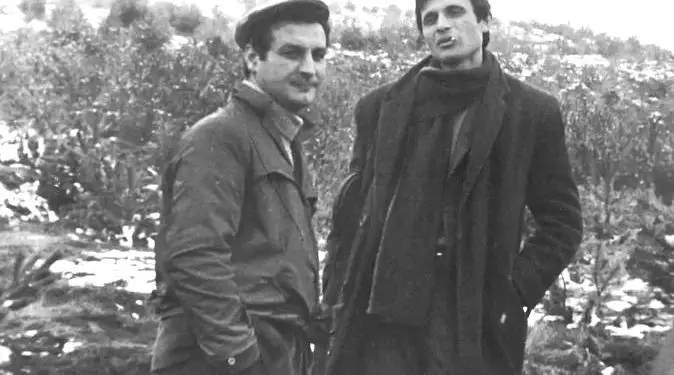

All joy awaited us and we enjoyed ourselves that night. Until recently, there was talk about Korça, where they would make a film. Spetimi talked about the script with enthusiasm, and this enthusiasm was transferred to us. Mevlani, the director, proposed to him that they should leave as soon as possible, that it had started snowing in Korça and that it is everywhere in the script. We laughed once. I knew Salveti and when he was good spiritually, when he felt loved and appreciated, he fell apart. That night I thought to myself: “Mevlani lucky dog, found a man”. That’s how they made the TV documentary “Korça”. It talked about the people of this city, about the snow, about the cleanliness of the premises, of the houses. Speaking of the textile workers, on whose breasts the birds sat, the announcer said: “And on them, the heavy hand of the leader.” Salvation had not told me anything about this before.

The show just aired. I was worried. At the entrance of the Radio-Television building, he was talking to a group of cameramen. I pulled him by the arm: ‘You’re in your right mind, but what was that: the heavy hand of the leader’?! “They didn’t catch it,” he said, “they gave it away”! ‘Yes, they can catch him later,’ I said. “You don’t live in fear,” he said. The show was liked, no one mentioned the “heavy hand”. At that time, he wrote the script for the city of oil workers, Kuçova. Both of these scripts gave him wings to write the script “Berati”. Those days when they were shooting for Berat, he took the whole group to his fathers in the evening. They slept and ate there. Our city is close to Berat. “My father is an artist, – he said. – To understand what kind of film we have made, we have to see his attitude. If he sheds tears, then we are fine. Don’t forget to start a conversation on a medical topic, because he likes medicine, he reads a lot of medical literature.”

Berat, his hometown, is two thousand five hundred years old. The Salvation scenario did not begin with the snowy Tomori mountain and the striped Shpirag, nor with the Osum river, which winds through the middle of the city. It started with the castle and the different names of the city, over time. The film had light, space. The city of a thousand windows, Berat has many windows and they are placed one above the other. It communicates not only through the alleys, but also through the windows. I saw the movie in the studio and I liked it. On the day it was to be broadcast, I was in Gjirokastra, it was October, and the Folkloristic Festival always took place at this time, because Enveri had the date of birth and Gjirokastra was his birthplace. I had gone from the newspaper to write. I was eagerly waiting for the hour when it would be televised. Instead, something else was given.

I called them the next day. “They stopped him, – this was his first apology. – We will talk when you come.” My arms were cut off. When I returned to Tirana, meetings began on television, they rejected the script “Berati”. Like all his writings, humanity and tenderness stood out there. But it was a crazy time, which only fabricated other scenarios, with enemies and saboteurs. The creativity of Salvation was far from this spirit. With that purity of hers, she seemed to be mocking this soup that was being cooked and so; “she was struck in the tender flesh, in the eyes, in the limbs, wherever she might live.” This phrase is of Salvation, so he had noted, above the manuscript of the “Berati” script, after the meeting. In those long meetings, Salvation suddenly happens not only without friends, but also among artists. How to protect “Berat”?! They were tearing him to pieces…!

“What is this, that people are begging from each other”?! There was a very human scene, the women give and take from each other, through the window, a pan, a rolling pin. “Why are we so poor”?! he said discussing the director. Even about the war part, there were arguments. There was a small scene where an old woman says: “In war, we warm ourselves with the fire of burnt houses, in peace, we wash our clothes with their ashes.” It is pacifist, against the war. “The Germans have burned a house in Berat, they are burning all of Berat,” Shpëtimi noted in the notes of the meeting. At the meeting, only one stood up to defend him. It was Ana.

This is how their acquaintance began. She was a charming girl, blonde, with dark brown eyes, red lips, but a little short. At that time, she was thin in body. She was done with philosophy, she was smart, which was noticeable at first glance. Her family was closely connected to the government. She had only one brother, mother and father. At that time, Salvation had not yet talked about this relationship, I don’t know the reason! He finished his internship and was preparing for the choir. I forwarded it. He would stay at home for a month. He was always happy, when he went home, he felt good, he loved Mira and Petrit very much and tried to make them happy.

Especially after his mother’s death, he was very careful with them. Mira had entered a temporary job, in the civil registry office. He had school in the evening, because he changed it when his mother was alive. Now that he was alone, he was consumed by the house, that’s why his father arranged for him to work. As always, with that spirit of sacrifice for us, she had collected the money to give to Shpetimi when he went to the choir and a part to spend when he came home. They “had a real party,” he told me later.

Salvation had told Mira that he loved Anna, he had talked to her about her and she was happy, that’s how Mira is built, she is happy for others, as if she were herself. In fact, when Ana went to our town to meet Shpeti, Mira had fixed the house, but she hadn’t laid the good carpet yet. When Ana came home, the first thing they did was lay out the carpet. They both laid him with Salvation. He said, “I don’t want Mira to be upset. When she comes, she must think you found her laid. That’s the way she likes it.”

When he introduced her, he said: “The best sister in the world. Only one thing I don’t know is that she moves like an ordinary person among ordinary people”, and hugged her tightly. Mira liked Anna, let her never insult anyone, and when it comes to feelings she says: “But why interfere, he knows it himself.” She has a habit: she will never hurt anyone; she is very delicate. This is where they mature as characters, this is where they part with me and my father. Last night, the next day Shpëtimi was to leave for Tirana, father was sick. There was pain in the kidneys. They were both told to take him to the hospital, but neither Shpetimi nor Mira wanted to. “What if there is nothing important, how can we be ashamed”, they said among themselves, since they thought that the father, being the wonder, might not be objective.

“I’m peeing blood,” the father told him. Only then did they take him to the hospital. The doctors laid him down. The rescue, the next day, went to the hospital. They didn’t let him in. “I’m leaving,” he said from the window. “Have a good trip!”, said the father, and so they parted. He came to Tirana and together we started trying to prevent him from going to the choir.

“I can’t stand it. I’ll cut my hair, I’ll dress as a soldier, I’ll train, I can’t”. Talked to H.P., the editor of a military magazine. He proposed to write a script for them and for this to stay in Tirana. We were both when he met her to get the answer. Salvation talked to him; I waited a little further. When he came, his face had changed. How today I remember those words; “They don’t want to keep me here, in Tirana. I don’t know the reason, I’m racking my brain, but I can’t find it.” Who were they?

It was about the Ministry of Internal Affairs, about its deputy minister, to whom the man from the magazine had addressed to remove Shpteim from the choir. I didn’t pay attention then, I passed them easily, but later I came back to these words who knows how many times. We started our efforts at the military hospital. Since he had undergone two facial paralyses, we asked to issue a report to postpone military service.

On one of these days, I met Anna. I took the Lapraka bus, it was about ten o’clock, there were few people on the bus. I was dressed in black; I still hadn’t gotten over my mother’s mourning. A blonde passed me. I don’t know why I thought it wasn’t her, now he had told me about her but I hadn’t seen her yet. At the station he was waiting sitting on the side of the road, the blonde passed him. I met Shpetim, he called: “Come Ana.” This dog. I don’t know what I felt. We shook hands. We had to call someone. We entered a small post office, located near the poplar road that leads to the hospital.

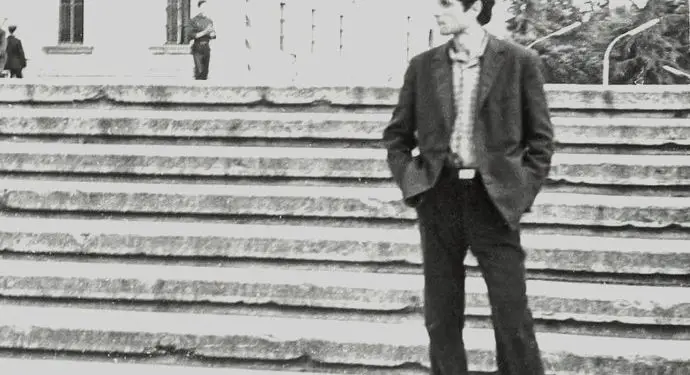

Ana waited for us outside. “Where did you find this”? I told him. He filled his eyes with tears, did not speak. He cut his face. I don’t even know, but for him, maybe I would like a star, super beauty, while she was and short, I don’t know how I felt. Maybe disappointed. Later, she told me this conversation between them. “I didn’t like Adelina. Do you think she’s better than me?” “If you’re going to stay with me, don’t even touch her with a feather,” he told me, and he was so determined. I realized what a place you mourned him. And shut up!” Our efforts were in vain. He was not exempted from military service, only that he received a medical report for limited service. That morning I walked him to the train. Zbori took place in Mamurras. He had a bag of books and a play he was thinking of presenting in August, when a contest had been announced, a pair of gray pants, a pink checkered top, and a change of clothes.

Kanotiere had bought them yellow, while he asked me to find them dark, because the helbets there could not stay as white as he would like. Salvation was very clean and he washed his clothes with care. So, I found blue underwear. “There they give them white, he said, but I want them in color”. I had bought something to eat on the way. Rescue always had a good appetite, ate a lot and was so elegant. I stood on the platform until the train left. And I slowly went back to work.

June is beautiful in Tirana with that bright summer sun, but without its intense heat. There are chestnut and linden trees on both sides of the road and the air smells of honey. Every day I went to work, edited, wrote an article, went out with Sadija, we worked together. I often had dinner with her. She had two children like light, I loved them, I especially loved Artan. He was very charming and apparently, he loved me too. Even though her husband was the head of the League of Writers and Artists and she was a journalist herself, she worked all day for the family.

I remember those simple dinners. Even the mayor was poor like everyone in Albania. I remember that when they got the new house, to the map, they transported the spoils at night. In order to fix it, Sadija found some of her husband’s cousins, who make some simple cabinets, bought an aunt’s carpet, it was big for the corridor, but Dritëroi’s studio was left with a simple carpet and those wooden shelves. board, but there were many books. There were always guests and brandy. There were times when Sadija, who tried to stop drinking, took the glass from him, twisted her face and drank it herself. “It’s good for my throat,” he justified himself. There were nights when he was late and she anxiously waited on the balcony smoking a cigarette. Sometimes, Sadija would also bring me a glass of brandy. Dritroi lost his shyness and read us a poem he had just created.

Once, when I got sick, I stayed with them. Sadija brought me the doctor. Apparently, he liked me and came to see me twice a day. Xexheja was waiting for him well, the elders want to treat him well with the doctors. One day, Driteroi met the doctor on the stairs. She looked at the flowers he was holding and said: “You still haven’t healed Adelina”?! The doctor did not appear again. When Sadija went to Ohrid for five days, she left me and my sister to take care of the boy and Dritëroi. In those days he was the most exemplary man I have ever seen. He came early in the evening, locked himself in the studio, came out to eat dinner in the kitchen. One day, Sadija ran out of money and she asked me shyly from the household money, I could hardly contain my laughter.

It was July, it was the army holiday, Artani where had he gone. When we remembered, he was nowhere to be found. Sadie’s sister and I were also worried where we didn’t ask for her. We finally found him sliding down the steps of the Palace of Culture. He was dressed from head to toe. We grabbed him by the arms. “You black man, I’ll give you a beating, so you’ll remember it for the rest of your life,” I told him angrily. “Okay, he said, how are you going to beat me separately, or both at once?” I lost my temper, I laughed. We cleaned it up quickly, I didn’t want his father to find out. Jokingly, I told him Dritëroi said that I will make a book and I will call it “Notes from the house of the president of the League of Writers and Artists” and I will publish it in the West. “Yes, Dritëroi said, you are a good journalist, for scandal columns” and he would say seriously. I would add: “And I’ll get the Nobel Prize.”

After a few days I would leave for Shkodër with a service. As every year, the Children’s Music Festival would take place at this time. I was covering art and culture issues in the newspaper, so I was going to write an article. Two retired teachers also worked in the newspaper for two hours a day, dealing with the arrangements of newspaper collections. That day, I was invited to have a coffee. I willingly agreed. They were good people and they loved me. Inside the department there is a small cafe where you can drink coffee and eat breakfast on foot. They ordered coffee and leaned against the counter.

I realized that they had something to tell me. One of them, Uncle Aristidhi, I had as a savings bank, because I gave the money, I saved to him to keep for me. When he needed them, he spent them and replaced them again. He told me: “We have a request. To give you some of the money you have with me and to buy colored dresses, you take off the black ones, we can’t look at you like this.” “Black begets black,” said the other. It had been two years since my mother’s death, I was used to this outfit, maybe I didn’t do it out of habit, but what a feeling, maybe I really thought I was doing it for her. They were right, because I was young. /Memorie.al

The next issue follows