By SIMON MIRAKAJ

Part thirteen

“Camps under the shadow of Tomorri, 44 years of internment”

– Memories –

Memorie.al / I put these memories down on paper after a long period of hesitation. This is probably because the subjects were always fresh in my mind, which followed me mercilessly during the years after the fall of communism. But there comes a moment – when time takes its course – and the images of horror and suffering came fading to me – almost the suffering passed into oblivion. Then I decided to repeat the most impressive events – first in my mind – until they took the form of these narratives. As dim as these accounts may seem – they create the idea of the harsh reality and misery of the camps.

Continues from last issue

We had the closest house, we all came and hugged each other and drank a glass of brandy and each went to the family.

What about now…?! Now straight to my sister, then to Gradisht, to Mojsi, Xina, Leka and Nan Palja, who we had as our nana. When Nan Palja saw us, she called Klora, the daughter of Pashuk Mirakaj, who was killed on the run in 1946.

“O Klora, the boys came”! – He put his hand on his heart. We quickly grabbed her and hugged her. She wiped her tears asking?

“Did you get released”?

“We were released.”

Now, after many years, a document has been released from the Archive of the Ministry of the Interior, when you look at it, you can’t escape emotions. That proof takes you back to those terrible years, where hard work and uncertainty about life appeared every day.

In addition to the appeal that we were forced to present two or three times a day, we were monitored every minute and second, in every movement, by their people. Every day we prayed to God to give us strength, so that we would not die. They declared in every meeting that; “They would make life boring for the enemies we have here.”

“I’d rather die in my arms, like men, than live like a reptile.” This was our prayer; you have to face a criminal state, which we had on top, as we were given sentences every five years.

To communicate the punishments, the Home Branch had appointed an officer of the Branch. Once they brought us a border officer, with the surname Shambro – he was from Krutja.

Later they appointed a police officer, Rexhep Çuko. When we returned from work that day, the appeal manager, Bakiu, comes to us and tells us:

“Come to the Council office because an officer from the Lushnja Branch has arrived. We got ready and made our way to the office, where the officer was waiting for us. We knew the reason of his coming, that we had fulfilled the eighth punishment, of repetition. We were not impressed, we knew that we were condemned for life by those criminals, but we believed that there is a God who will save us one day.

Sokol tells me, when we were approaching the office:

“He will ask us to sign that we received notification of the punishment, but we will not sign it.”

I tell him:

“Let’s sign it and not make trouble for ourselves, how we signed it and how we didn’t sign it, we have five of the penalties.” At these moments we went inside.

The officer took out a piece of paper and read:

“Sokol Pal Bib Mirakaj, your sentence is repeated for five years. Simon Pal Bib Mirakaj, your sentence is repeated for another five years. Sign here that I informed you”.

“You don’t sign” – said Sokoli, – no we don’t sign”, I told him and we left the office.

So in June 1989, we were re-sentenced again, with another five years. As I said, God is great and he saved us from these criminals, freeing us on July 4, 1989. We were freed after 44 years, of a very long and very difficult journey, completely innocent.

They called us “enemies”, but we were enemies of the injustice dictatorship that communism caused for 50 years, they were enemies of Freedom and Democracy. Every time has its heroes.

Please tell me:

“Have you heard that the other was sentenced for 44 years, without doing anything”?!

SECOND PART

LIFE AFTER THE DICTATORSHIP

The sea is my dream

A few days ago I had won my freedom, the right to move around Albania. My mind was stuck there, on one question, when will I see the sea… when?! I had seen the sea on the map – I knew that we have a coast of four hundred kilometers, but I had never touched its water, nor had I seen its immensity, I had heard that the water is salty; I had seen the sea in movie, the people who bathed lay on the sand.

I had read the novella “The Old Man and the Sea” by Hemingway, I had created an image of the sea and its beauty. And when I would touch his warmth? When would I lie on his lap?! I didn’t even know how to swim! I had washed myself in the canals, with water up to my knees. I had escaped the appeal of the police, now I only had one appeal, that of work. My sleep had been killed; I had a reflex to get up at five o’clock. I used to get the work plan from the brigadier, now they looked at us with a different eye. I say to my brother Sokol:

“I will leave for Durrës, I will go to the sea”.

“Okay, go; be careful, because you don’t even know how to swim well.”

“I’m going with the sea, I’ll introduce myself to you, and I’ll ask him if he accepts me…”!

“Remember operative Kosta Sillo, when we asked him for permission to go to Savër, he told us:

“Savra does not accept you…”!

“Take leave of the brigadier, don’t forget”!

Sokol told me:

“We were not given permits”!

I left the house and saw the brigadier handing out the work plan.

“Hey, – he told me…! – You weren’t for work today”, after seeing that I wasn’t dressed for work, I was wearing a pair of dock pants and a short-sleeved shirt.

“No, I came to ask for permission, for two days…”!

“What do you say Monçi, how much do you care”!

“Thank you! – I left. I went out into the street waiting for some vehicle. The bus came to Gurëz, it also stopped in front of Gjaza, where I lived. It arrived at eight o’clock, it was a bad bus that seemed to be giving up, I went up and took a seat. It seemed to me that everyone was looking at me. At ten o’clock we arrived in Lushnje, I went to the train station, cut the ticket and sat on a bench waiting.

I had seen the train for the first time, when I was working in the hills of Dushku, to travel by train, it was the first time. I heard the sound of the siren, I saw people rushing to get on, and there were many people, probably going to the beach: it was July, very hot. The train started, I was sitting in the corridor, at the window, I wanted to watch.

Here is Rrogozhina! A few got off, the train started again.

“And now,” I asked someone nearby, “where do you stop”?

“Stops in Kavaja”.

“Which station is closest to the sea, Golem’s?” Please when we are close, can you show me?’

“Of course”.

I took out a ‘DS’ (Durrës Special) cigarette, offered it to the passenger who was going to help me, he said:

“Thank you, but I don’t turn it on; we’re getting closer to the Golem.”

“Ooo, here’s the sea” I shouted.

“You have never been to the sea”? – asked the passenger who was next to me. Without turning my head, I said: “No”.

“Excuse me, haven’t you gotten out of jail”?

“No, from exile,” I told him.

“I am thankful that you have been released, I also have my uncle behind me in prison… and meanwhile the train stopped…!

“Get off,” he told me, “this is the Golem, be careful when you cross the road from the cars.”

“Goodbye”! – We said hello.

What about now?! I crossed the road, I saw people heading towards the sea and I was walking behind them. After five minutes, I reached the beach. The beach was full, the blue sea stretched before me, endless. I walked on the sand and, at the end of it, I sat contemplating it. I took off my sneakers, pulled my pants up to my knees, and went into the sea.

I lost my mind, went out and sat down again, lit a cigarette and watched its smoke disappear into the hot air. I watched people lying on towels, others bathing. A voice from inside addressed the beachgoers.

“Hey, do you know that I see the sea for the first time”?!

I put out the cigarette and went back into the sea, on its shore. I filled my fists with water, washed his face, put some water on his lips, but it was salty. I went a little deeper, until the water was up to my knees, and I walked in the water. I sat for two hours, contemplating, got dressed and went out on the street, to the train station, to return from where I had come. The dream of seeing the sea came true at the age of 44!

Gjaze, July 12, 1989.

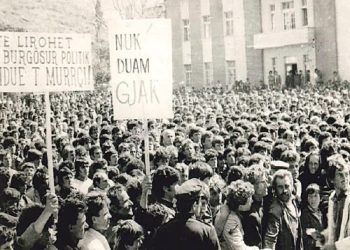

The fall of the dictator’s bust

-February 20, 1991-

33 years have passed since that day, a day which will hardly fade from our memory. It had been a while since we had gained our freedom, better to say, the chains had been untied from our hands and feet. That you cannot be free, when you have neither property nor home, we were both taken from us, and our lives were taken from us. We had won something, we would no longer appeal, and we would no longer ask the operative for permission to go to the city or, to the sister and brothers, who were in another internment camp.

We went to work every day, we worked until lunch, we couldn’t stay longer, we didn’t get tired, and the days didn’t resemble each other. Dictatorships were collapsing, the handheld radio accompanied us every day, keeping us up to date with events, and we listened to the news. We were aware of the events of the overthrow of communism, which had caused so many tragedies.

From 1:30 p.m., I left with my brother Sokol to Deda’s, where we found the brothers Dine, Tomorri and Sazan, as well as Pal Kazi, Frida Sadedini, who lived with the Markagjones.

As soon as we said goodbye, Frida took out the cards, prepared the poker table. We played poker, to kill time once in a while, we played with pennies, ½ ALL grains, and the excitement of the game was like playing with millions. On one tour, I didn’t join the game and was watching the game, when from 2:30 p.m., I heard the children shouting: “Uncle Enver was thrown.” I immediately came out, the children were shouting loudly: “They threw the bust of uncle Enver”.

I entered the room: “Turn on the radio to listen to the news that the dictator’s monument has been torn down.” The Albanian Radio-Television journalist, Alfons Gurashi, broadcast the moments of the fall, the game was certainly interrupted, an unprecedented joy, unrepeated emotions. We left Deda, for home. We were listening to the news.

At 18.00 we turned on the TV, Alfons Gurashi or someone else had filmed the fall of the monument, we were stunned, watching the crowd of people near the monument who threw the rope around his neck and dragged him away. At the moment they threw the rope, we prayed to God:

“God saved those people”, – because we were afraid that when it fell, no one would die. The monument was covered by people riding on it and dragged by the car. We celebrated with a delicious dinner, wiping away tears of joy.

I remembered the words of the late Deda, who on a walk we were taking together, taking the pipe out of his mouth, said to me: “Simon has dropped a metal, a metal monument has been dragged, not communism”.

Today, after 33 years in democracy, despite some achievements, his statement seems prophetic to me. Memorie.al

The next issue follows