By Prof. Dr. Përparim Kabo

Part one

The Bloody Hungarian Revolt, the Revolution of 1956

Gorbachev’s acceptance of the unification of the two Germanys on the 40th anniversary of the creation of the German Democratic Republic goes beyond a geopolitical assessment of the post-WWII era. It was not merely the acceptance of a union in the framework of an expanding global market, which, as Mikhail Gorbachev stated, “Did not conflict with the new policy’s (Perestroika) assessment of this fundamental issue.” But there are also two pivotal factors that play the main role in judging this event: the unification of two countries with opposing systems-capitalism in the Federal Republic of Germany and communism in the German Democratic Republic-and the latter’s shift to the side of NATO.

If we count down from 1989, we can go to 1968, when Soviet tanks militarily occupied Czechoslovakia, a member country of the Warsaw Pact, since “the sovereignty of communist countries was limited within a broader sovereignty, that of the socialist camp.” This intervention was based on the “Brezhnev Doctrine,” which stated: “When forces hostile to socialism try to turn the development of some socialist countries toward capitalism, it becomes not only a problem for the countries concerned, but a common problem for all socialist countries.”

This thesis was denounced 20 years later in 1988 by Gorbachev, but 12 years before 1968, specifically in October-November 1956, this militarist and anti-democratic doctrinal essence was used by Soviet forces to suppress the broad popular, political, and anti-Soviet movement in Hungary. Today, after 50 years, the return to this event goes beyond the narrow interest of the history of this country and this people, which since 1999 has been a member of NATO and since May 1, 2004, a member of the European Union.

It is a commemorative occasion, but the half-century time span allows one to judge and evaluate what that event was. Was it a revolution in the classical sense, because it sought to change the system, since communism was considered a system imposed on post-WWII Hungary, which paid this price because, at its end, as an ally of Nazi Germany, it found itself occupied by Soviet forces? Was it anti-Sovietism, as Hungary sought to become a neutral country and withdraw from the Warsaw Pact?

Was it a nationwide effort to shake off the ideology and policies imposed in all areas of life by the communist system brought to Hungary by the post-WWII occupier? Because it is a fact that communism, as an economic and social system, is an expression of the interruption of the proprietorial and institutional continuity of the historical progression of anthropology.

For it was a system that denatured human history, imposing a totalitarian political organization, a ferment of revolutionary enthusiasm that, subjectively and radically, for several decades, forcefully hindered human development by unnaturalizing property relations, collective and representative democracy, and the fundamental relations of society.

But it was also a reality imposed on those countries that had no ties to communism before World War II, while at its end, in global geopolitics, they remained zones of Soviet influence and were further institutionalized as communist states and satellites of the communist giant, after joining COMECON and the WARSAW PACT.

In this anti-Soviet and anti-communist popular effort were also Hungarian communists and their leaders, who after the XX Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and Khrushchev’s speech on the crimes of the Stalin era were included in what is known as the process of de-Stalinization. Of course, as in the former Soviet Union and Hungary, regarding this phenomenon with a tendency toward the democratization of life and more freedom and humanism within the same system, there was a regrouping of high-ranking communist leaders, some in favor of this process and others against it, into anti-Stalinists and pro-Stalinists.

At any rate, the broad Hungarian popular movement of October 23, 1956, first turned to the statue of Stalin near the Parliament building and pulled it from its pedestal, toppling it to the ground. Stalin’s boots remained on the pedestal. The Hungarians placed their national flag there without communist symbols, but only with the three colors: white, red, green.

It’s interesting. Even when the English soldiers pulled down and toppled the statue of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, the boots remained on the pedestal. The most expressive part of their savagery in human morphology as clothing. Those that embody the merciless oppression of people and nations. When the young Hungarians of 1956 rushed toward the Parliament, enthusiastic about the return of Gomulka in Poland, these liberal and anti-Soviet communist, Hungarian military officers also joined them, who tore the Soviet stars from their uniforms and joined the crowd as fellow patriots. The presence of Soviet garrisons, even though they were dislocated in areas outside the cities and lived a garrison life, could not be endured by the Hungarian people.

After all, the presence of a foreign army is an indicator of being possessed, and sovereignty and independence are delegated to the occupier. Historical debates have also focused on the view of this revolution from above, that is, how it was conceived in the Hungarian communist leadership of the time. The main assessments of the nature of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution that are still debated are: that it was a socialist and democratic revolution, which aimed to create a socialist society like in Yugoslavia, or a social-democratic society like in Sweden, or perhaps another kind of socialist system, a system controlled by the people and workers, and represented an original goal.

This view was popular among reformist communists and social democrats, but also among Trotskyists and others. Regardless of the specific profiles, these groups had in common their rejection of the Soviet system. There is a viewpoint that the massive uprising of 1956 is considered a spontaneous revolution, aimed at achieving political self-determination, including social contexts, particularly in terms of alignment with the states of Central Europe. This view was popular in Hungary, but also in the countries of this region.

In another perspective, the Hungarian uprising of 50 years ago is considered a liberal and anarchist socialist revolution, which aimed to create a new kind of society, modeling the country on the Hungary of workers’ councils. This view was widespread among liberal communists, communist councils, anarchists, and some Trotskyists. There is a viewpoint that it was a parliamentary democracy revolution, with the main goals being the establishment of political independence from the Soviet Union, in close cooperation with Western Europe and the USA, to bring back parliamentary capitalism in the form of Western Europe.

This assessment has popularity in the USA and much less spread in Hungary and Central Europe. Such a judgment is the product of the clash of arguments from the two main sides of the Cold War period, the Soviet Union and the USA. The part of historiography that clings to this definition is overwhelmed by the thesis that a front of organizations was heavily supported by the CIA until the mid-1960s.

Finally, it cannot be left unmentioned that Russian and Chinese communist historiography, which has considered this effort of the Hungarian people as a clerical and fascist effort, with the aim of re-establishing a “Horthist” government or a government with a political arc, with the aim of creating a semi-feudal system and a capitalist economy.

In support of this completely wrong and radically subjective judgment, other communist parties also came out at the time, including the Party of Labour of Albania, and especially its high leadership, which did not hesitate to strike to death every symptom from its very beginnings, not just to change the system, but also the smallest purposeful and sincere impulse for a departure from Stalinist aggression and brutality, for a more democratic and humanist spirit within the communist system of the dictatorship of the proletariat itself.

The judgment of 1956 on this anniversary is possible to be made as freed from ideological and emotional burdens, but also from censorship and self-censorship, which prevent some bitter truths from coming to light, which as occult mechanisms may have manipulated the dissatisfaction of the Hungarians, who at that time took to the streets and ended up under bullets, artillery shells, and aerial bombardments, as if they were not a dissatisfied and demanding people, but an enemy army on the front line, where such a match makes sense. In this line of reasoning, it is acceptable to say that in the moral aspect, the bloody suppression of this battle, which had as its main missioned “a freer and more democratic society,” is a shame of the mid-20th century.

The blood and ideal of the Hungarian people warned of the social-imperialist nature of the Soviet Union, and ultimately showed that the imperial nature and interests of the USSR had not changed from those of the former Russia of the Tsars. The new geopolitics of the post-World War II era, accepted not simply as a change of borders, but as a change of systems, in a cold post-arithmetic, showed the West, at that time, that the calculation of the war winners had not been made correctly and the tolerance of Soviet influence had been a folly with epochal costs for humanity.

The experiment with communism in many countries in Europe and elsewhere resulted in a waste of time, energy, human lives, funds, and investments. As if to say, for decades they walked on rails that seemed to help the train move, but which in fact were getting further and further apart, and the world, sooner or later, would have to go off the rails, because communism and capitalism could not coexist. The events of 1956 in Hungary warned of such a thing, but it was too late, as the relationships had been established and written in Tehran and Yalta.

Hungary of 1956 and the events packed with a strange dynamic showed that the victory of World War II had not been complete, because fascism was destroyed, but after it, communism, which is just as totalitarian, expanded. They showed that the war was won, but peace was not, because the created relationships were conflictual for the fundamental problems of human freedom, such as property, the democratic system of representation, school education, the relationship with land, and relations with religious belief.

Therefore, in summary, it is fair to say that the Hungarian popular revolt of 1956, carried out from below, as an all-inclusive movement of anthropological masses-students, workers, peasants, military personnel, writers, officials, and intellectuals in general, unions, and people of religious faith, etc.- with the aim of returning to the former pre-communist system, represents a popular revolution. This massive movement was inspired by the Hungarian revolution of 1848.

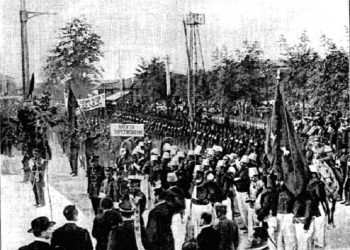

The mass of Hungarian students who first took to the streets, under the example of what had happened in Poland in June 1956, in the Poznań workers’ revolt, a preparation that had been going on for several weeks, culminated on October 23, by marching to the statue of the poet Sandor Petőfi and the Polish general, Jozef Bem, a hero of the 1848 Hungarian revolt.

The reference to this revolution is also related to the national consciousness of the Hungarian people, since with it, the creation of a Hungary integrated as a territory and with an independent state and institutional system within the Austrian Empire of the time was achieved. As if to say, that revolution and the two or three decades that followed, built the Hungarian state and nation, so any attempt to take away this independence and this sovereignty could not fail to touch the feelings of the Hungarian people and could not pass without a popular reaction and opposition, regardless of the cost.

The Intervention…

On November 4, 1956, the plan that had been changing for a few days began to move. Within the Presidium of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the hardline faction of Molotov and the followers of the harsh Stalinist line had won. Khrushchev and Zhukov, who were initially reserved about a broad intervention, believing in a possible management from within, were defeated in the vote that took place in the high forum of the Soviet leadership of the time. The second Soviet intervention, completely different from the first on October 23, 1956, was broader and was based on a combination of all land and air forces. The Soviets brought 6,000 tanks to penetrate the urban areas. The intervention was motivated on the basis of the responsibility of the Warsaw Pact and with the approval of the Kadar government, which was formed on November 3.

While the Hungarian army was in an uncontrolled resistance, this role was played by the classes that resisted, organized by the councils, and for this reason the industrial areas and the workers of Budapest would be the first to be hit by Soviet artillery and aviation.

These actions continued in an improvised manner until the workers’ councils called for a ceasefire on November 10. From November 10-19, the workers’ councils negotiated directly with the Soviet occupying forces. While they achieved the release of many political prisoners, they did not achieve their goal of the departure of the Soviet forces.

Not only was the main request-withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact-not realized, but it was proven that this treaty could also occupy militarily, even though the member countries of this military and political pact controlled by the Soviet Union did not supply troops for the military intervention. The post-arithmetic of the event speaks better with the numbers.

Thousands were arrested, imprisoned, and deported by Soviet troops to prisons in the Soviet Union, many of whom without any proper documentation that could prove their participation in the clashes with Soviet troops. 200,000 people fled to Austria and Yugoslavia. 26,000 were brought to trial by the Kadar government and 13,000 were imprisoned.

In CIA documents from 1960, approximately 1,200 executions are reported, although Hungarian authorities estimate around 350 executions. Sporadic armed resistance continued until mid-1957, causing a substantial hindrance to the country’s economy. As of November 8, almost all of Budapest was under control.

Janos Kadar became Prime Minister of the “revolutionary government of workers and peasants” and General Secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party, which was renamed the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party. Many Hungarians joined the reorganized party, which was cleansed, and every new admission was made under the supervision of the Presidium Committee of the Soviet Communist Party, led by Malenkov and Suslov.

After 1956, the Soviets tried to dismantle the Hungarian army, accompanied by a political purge and indoctrination. In May 1957, the Soviet Union reached its troop level in Hungary, and by treaty, Hungary accepted the Soviet presence on a permanent basis. Imre Nagy, the heroic man of this revolution, along with his inner circle and some high-ranking former leaders who were shot, found asylum in the Yugoslav embassy when Soviet forces descended on Budapest.

After being assured by the Soviets and the Kadar government of a safe passage out of the country, Nagy and his group left the embassy on November 22 and went to Romania. He returned to Budapest in 1958. Nagy was executed along with Pal Maleter and Miklos Gimes, after a secret trial in June 1958. Their bodies were placed in an unknown grave in a municipal cemetery outside Budapest.

In 1989, after the fall of the Kadar government, Nagy’s body was reburied with full honors. From 1963, many of the political prisoners of 1956 were released. During the Soviet attack in 1956, Cardinal Mindszenty was granted political asylum in the US embassy, where he lived for 15 years, refusing to leave Hungary, although the government changed his 1949 treason charge. Due to his weakening health and the constant request of the Vatican, he finally left the embassy and went to Austria in September 1971.

Today his tomb is in the Esztergom Cathedral, a city not far from Budapest, which was originally the first capital of Hungary. (The author of this article, in the summer of 1992, for the first time, but also on every occasion he visits this cathedral about 140 meters high, has knelt at the tomb of Mindszenty, whom he had first met as a name in the distorted history that was taught in our schools during the time of communism in Albania).

It should be kept in mind that the Hungarians, since the creation of the Hungarian state in the year 1000, have been Roman Catholics and linked to the Vatican. Such an affiliation in European civilization did not please Russian Orthodoxy, which in the 19th century had more than once intervened to interrupt the historical course of Hungary. Therefore, the 1956 intervention could not have been immunized from this historical pathogen in the Russian-Orthodox subconscious and sub-psychology. After the fall of communism, the Republic of Hungary on the 33rd anniversary of the events of 1956, in 1989, declared October 23 as a National Holiday of Hungary. This act contains the message that those events have as their super-value the interests of the nation and its progress.

It joined two other celebrations that of August 20, the formation of the Hungarian states in the year 1000, and March 15, which evokes 1848, the bourgeois democratic revolution of Lajos Kossuth. For Hungarians, the homeland, freedom, and the rights of Hungarians are above all else; for them, they are always ready to take to the streets, as they proved a few weeks ago, even in the face of a lack of sincerity from the Prime Minister.