By Franco Benanti

The third part

Memorie.al / The Second World War had a powerful impact on Albanian lands as well. Much has been said about this by our historians, in the communist spirit. The generations before 1990, have learned this from textbooks, from the History of the Labor Party and the History of Albania, but very few eyes have been familiar with the alternative treatment made by historians and non-communist authors, inside and outside the country. In this regard, the book “La guerra piu lunga” by Franco Benanti, a former doctor in the Italian occupying army, in the Balkans and Albania, published by the house “Mursia” in Milan, is of great interest (first edition in 1966, followed by four reprints later).

Continues from the previous issue

Doctors, engineers, surveyors, industrial entrepreneurs, dentists, nurses, pharmacists, agronomists, veterinarians, etc., were mobilized in the service of the government, military commands or the National-Liberation Councils of the prefectures, for the needs of reconstruction from the war and construction. Those who objected were considered saboteurs and were punished with license revocation, 30 years in prison, or death.

The fifth law concerned the requisitioning of building materials (cement, iron, lime, cast iron), lubricating oils, pharmaceutical products, means of transport (horses, donkeys, bicycles, motorcycles, automobiles and spare parts), foodstuffs (flour, grain , sugar, fat etc) and everything else the army might need.

Practically everything was requisitioned. Within 15 days, the Albanian and foreign owners had to report to the authorities what they had and hand it over voluntarily. On December 20, 1945, the Minister of Economy, Medar Shtylla, ordered the appointment of state commissars and controllers near industrial factories.

The help of the Italians in the reconstruction

Within a short time, all major roads were opened to traffic, as well as bridges. Of the 3,200 linear meters of the bridge, 2,500 meters were repaired, thanks to the hands and minds of the Italians. Therefore, 55 Italian technicians were decorated with the “For Merit of Work” Order. Several hundred Italian soldiers were also activated at work, waiting to be repatriated. Bedri Spahiu, inaugurating a bridge near Tirana, declared that; “we have fought Italian fascism and not the Italian people”.

Kosovo occupied by Titists

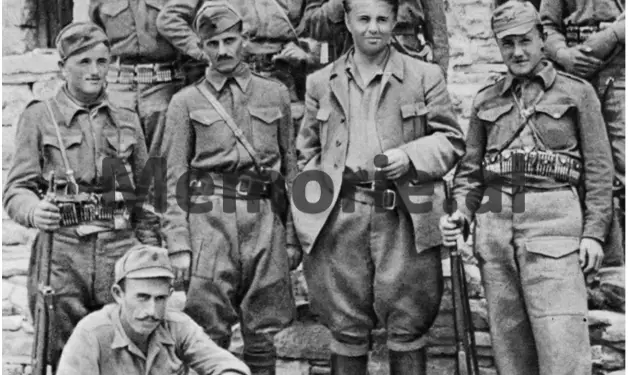

After the departure of the Germans, Kosovo was occupied by Tito’s army, which exercised real terror there. The Albanian irredentist movement in Kosovo, under the name “Besa Kombëtare”, under the leadership of several patriots, such as Ymer Berisha, Ejup Bunjaku, Haki Taha, Muharrem Bajraktari, etc., developed a powerful resistance, but was also bled by the Titists. Therefore, in 1945, Haki Taha killed Miladin Popovici in Pristina, in his office.

Many nationalists were arrested, shot on the spot, or brutally persecuted. In July 1945, Muharrem Bajraktari wrote, among other things: “At the end of the war, the peoples of the whole world won peace, while the Albanian nation, unfortunately, is suffering under an unparalleled terror, the victory of the communists. The government of Tirana, appointed by Tito, is an expression of the pan-Slavic will. The Albanian people are deprived of their rights and are being subjected to massacres”.

In the Korca hospital

I spent the first days of my service at the Korça hospital visiting Albanian partisans on an outpatient basis. The director of the hospital was Koço Lubonja, former doctor of the 20th Assault Brigade. He replaced Dr. Polena, who had gained a lot of respect in the city. Many civilian nurses were replaced by partisan girls, without any experience in this field. In the city, I met Italian colleagues. At that time, the section of the “Garibaldi” Committee, which protected the interests of the Italians, was created in Korça, headed by the former commissar of the “Antonio Gramshi” Battalion, Alfredo d’Angelo.

But he was arrested a few weeks later on ridiculous charges. I also went to the Catholic Mission of the city, which was run by priest Ernesto Cassinari. Through a UNRRA relief worker, I was finally able to get a letter with news of myself back home to Italy. Meanwhile, the situation of my compatriots in Albania was getting worse. According to the law no. 38, of February 1, 1945, the agreement with the National Bank of Albania, which was transformed into the Albanian State Bank and which absorbed the assets and liabilities of the Italian bank, was cancelled. The Italian staff was fired almost entirely.

At the end of December 1944, they arrested the administrative director of the “Italstrada” company, Tommaso Leonardi, whom a military court, without giving him the opportunity to defend himself, sentenced by firing squad. At the time of the murder, in May 1945, they did not even allow the service of the priest. A few weeks later, they arrested the engineers Andrea Tarasconi and Mario Cati, who were also shot, one night after the trial, and buried somewhere near Berat. The criminals took the expensive things, even the corpses, even the golden teeth.

Engineer Simoncini, manager of a construction site in Shijak, brothers Giuseppe and Renato Fassina, Mario Grossi and Giovanni Cantelli, owners of transport parks, had a similar fate. This situation encouraged efforts for a solution, for the repatriation of Italians. The “Garibaldi” committee accelerated the reaching of an agreement between the Albanian and Italian governments.

On March 9, 1945, the Undersecretary of War, Mario Palermo, came to Tirana and signed with Enver Hoxha an agreement for the repatriation of Italians. Among the latter, there were also 300 medical workers, who removed the black olives, all that time of terror, persecution and violence by the Albanian authorities.

Also 20 thousand soldiers, who had to board the ship in the ports of Durrës and Vlora. A group of sick women and children were airlifted. But, about 800 Italians were kept to serve still, in the reconstruction of the country, working without breathing, with extended hours even on holidays, for months.

Agrarian Reform and the fight against illiteracy

The government confiscated the lands of large farmers, such as; Vërlac, Biçak, Vrioni, Vlora and Resuli. He would immediately give these lands to the poor peasants, to use them until the Agrarian Reform took place. The old agreements between the owners and tenants, as well as the arrears, were cancelled. The reform law came out on August 29, 1945. But the land given to the peasants remained the property of the state, since the peasant had no rights to sell it, buy it, and give it to anyone else, for use.

Meanwhile, the government came down hard on the kulaks, the rich peasants who tried to disrupt the affairs of the reform, calling them saboteurs. Ten partisan brigades were involved in the “calming” of the situation, read: the physical annihilation of 2,000 kulaks. It is understood that despite the government’s incentives for work, the yield fell to such a degree that famine struck, so the government took grain from Yugoslavia, about 25,000 tons.

Another problem was illiteracy, which involved 80% of the population. In the entire country, there were at that time only 643 primary schools and 11 secondary schools. In 1946, the number increased correspondingly to 1097. 512 new schools were built, “with voluntary contribution” from the people. Teachers were trained by fast courses and by correspondence.

The conditions of the teachers were very bad. I remember a teacher in Korçë, who suffered from heart disease; they forced him to teach during the day in Korçë, in the afternoon in Drenova and in the evening in Boboshticë. To the teachers’ complaints to the minister, he responded by labeling them as; “parasites, simulants, lazy”. Illiteracy disappeared twenty years later.

Epidemic of typhoid fever

One night in March, a partisan of the 5th Division, serving on the shores of Lake Ohrid, was brought to the hospital. He had a high fever and blunted reflexes. The lab confirmed that he had petechial typhus. This disease had broken out a long time ago in Montenegro, Yugoslavia, where the 5th Division had also operated. After the first case, many other cases appeared, among the Albanian and Italian partisans.

The Albanian doctor Gaqo Ballauri, who dealt with these patients, got infected himself and died in the middle of April. The epidemic also spread to the population of Korca. The government asked for help from the Allies and from the Yugoslavs. The latter sent several anti-typhoid units and disinfection tools. Some young Albanians were initially trained for this job.

Yugoslav advisers set up the institutions in Albania

The Yugoslavs influenced the General Staff of the Albanian Army, its operational-tactical plans and brought the military manuals. A team of political governance of the Yugoslav Army organized the party structures in the Albanian Army. Through Vojo Srzentic, the Yugoslavs organized the state administration, various ministries, finance and economy, as well as all state services, according to the Yugoslav model.

They also helped in setting up military and civil courts. Major Tominsek dealt with this case, bringing his experience gained in the Soviet courts, Ljubyanka prison and other Muscovites. Finally, the Yugoslavs helped draft the constitution and prepare the elections. As a result, Enver Hoxha’s government received every directive, instruction, plan, program and manual from the Yugoslav government.

I was a witness when in Korça, a convoy of 400 “enemies of the people” passed, going to work on draining the Maliq swamp. Among them were former members of nationalist parties, such as ‘Balli Kombëtar’, ‘Legaliteti’, etc., as well as a group of German soldiers who could not leave Korça. Another 6,000 people were sent to build the road; Kukës-Peshkopi, in the north of the country. In addition to political convicts, the government also sent thousands of young people, as shareholders, to these types of jobs.

The war is over, but not for us!

On the night of May 9, 1945, we heard about the end of the war with Germany. Out of joy, I gathered with two Italian friends, Bellodi, Costa and Fischioni, at the latter’s house. The hope for repatriation now seemed more feasible. But a month passed and nothing new.

I continued to work at the hospital, non-stop. One day I went to the office of Dr. Lubonja and I begged him to give me permission to go to Tirana one day, to inquire why my letters were not going to the family. I saw that he did not like to give me permission. I persisted and he finally gave me permission, warning me that I might not be seen with good eyes. From who? I would learn this very quickly.

In the capital, I met other Italian friends, Professor Lozzi, Major Augi, Riccard Masnata, Moffa, Eugenio Condorelli, Italo Viti, Semproni, Armenio Caliri, Domenico Caruso and Vincenzo Castiglione. We talked about our common plight; the return to the homeland. I met several authorities, including the Director of Health, Dr. Sherif Klos, whom I met in March 1944, near the Sheper Command, and Colonel Beqir Balluku, the commander of the Second Assault Brigade.

He had become Deputy Chief of the General Staff and was covered with stars and decorations. In the outfit he was wearing, he looked like a porter of a luxury hotel in the West. My questions were answered in general terms. I returned to Korça, heartbroken. To my surprise, the director quickly called me to the office and informed me of my transfer, near the Berat hospital. The next day I went to Berat, where I met other Italian colleagues. On July 20, I was urgently requested in Delvina, where a malaria epidemic had occurred, with many deaths.

We hoped that the Italian consular mission headed by Turcati, which arrived on July 28, would do something for us. Hoxha’s agreement with Palermo had left us specialists in Albania with forced labor. Poorly paid, with no possibility of contact with the families, with whom they were separated many years ago, with no possibility of sending them any financial aid. As soon as he arrived, 800 Italian soldiers, who had been suspended in Vlora and put into forced labor, left for Italy.

It was now the turn of civilians to be repatriated. But the authorities brought out hundreds of obstacles, such as numerous interviews, with representatives of various ministries, with the Prosecutor’s Office, the Directorate of Finance, the Police, the General Staff of the Army, etc. Although the legal deadlines were ten, or 15 days, a mistake in one link was enough for everything to be repeated from the beginning.

Another star came out. For the necessary specialists, they should bring from Italy a specialist with the same qualification, for replacement. But hearing what was happening in Albania, which Italian would come to work in Albania? Thus, about a thousand Italians should still stay in Albania.

As for those Italians who were in prison, or in the interrogator, it was difficult to escape them. Lawyers who demanded that trial and detention deadlines be respected were threatened by the presidents of the courts, with unpleasant consequences for them. Many lawyers were arrested and sentenced. Meanwhile, the arrests of other Italians continued.

A new law on war taxes 1939-1944 (no. 37 of June 13, 1945) also weighed heavily on Italian entrepreneurs. The tax was 15% for smaller businesses, or 100,000 francs, and 80% for large businesses. or 4,000,000 francs. The assignment of the type of business was completely arbitrary.

For example, the Gambardella brothers had a shipping agency. The first time they were taxed with 90,000 Albanian francs. One brother went to Italy to collect the required money, while the other remained a hostage here. The amount was collected from the Albanian military mission in Bari. But the authorities took this quick liquidation as a financial opportunity for the brothers, so they taxed them again with 2,200,000 francs, still holding one brother hostage. The money could not be paid and the brother remained under arrest.

Elections for the constitutional assembly

As I said, I went to Delvina, where the XVth Brigade was in a miserable condition, due to malaria. Near Delvina is Saranda, a picturesque town, facing the island of Corfu? When you are there, you have the impression of freedom, because of the proximity of the Greek land.

In 1945, thousands of Albanians swam across the sea to escape to Greece. But, when the border police managed to catch them, the court sentenced them not as border violators, but as Greek monarcho-fascist agents. This was a way to hide the real motive of the escape.

South of Saranda, or on the Pal plain, there was a forced labor camp, which I saw with my own eyes, at the end of October 1945. There must have been about three thousand people there. The camp was surrounded by guards with machine guns. After 12 hours of work, people lay down to sleep on some boards, without any covering. Many prisoners suffered from scurvy, starvation, dysentery and general exhaustion.

I want to underline that, since 1945, forced labor camps would become a very important institution of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime. The implementation of the five-year plans would be carried out by slave labor, of real political opponents, or invented by the regime.

With the sacrifices of countless citizens, the swamps were drained and the land reclaimed, mines were opened and many industrial and residential works were built. This regime, before our eyes, was committing the same crimes as it once did in Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Mauthausen. Well, this regime was praised by some political circles in the world. Memorie.al

The next issue follows