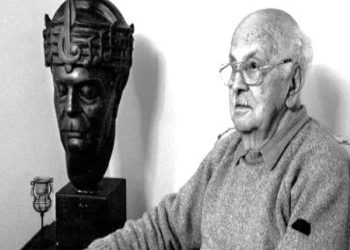

By Mehmet Mufti

Second part

Memorie.al / Mehmet Muftiu were born in Tirana in 1930. During the War period (1939-1944) as a participant in the Anti-Fascist National Liberation Movement, he was arrested, tortured and interned in the Nazi camp in Pristina. After his release from the camp, he returned to Tirana and was accepted into the ranks of the Communist Party of Albania and during the years 1950-53, he worked as a journalist in the central press. After writing a letter to the Central Committee of the ALP, denouncing as shameful the arrest of his colleague and friend, the writer Kasëm Trebeshina, his right to study at the “Maxim Gorky” Institute in Moscow was canceled, and he was expelled from the ranks of the APS are interned in the village of Shtyllas in Myzeqe. A temporary rehabilitation made it possible for Mehmeti to finish the Higher Pedagogical Institute “Aleksandër Xhuvani” in Tirana and to be employed as a teacher in remote villages in different districts. Based on this, in 1961 he managed to publish his first novel entitled “Leka”, but three years later, in 1964, the manuscript of the next novel “Skhrimtari” was considered reactionary and Mehmet was again removed from copyright and works as a cigarette seller for 26 years. With the collapse of the communist regime, after 1991, he appeared again with his writings in the daily press and managed to publish several books. Mehmet Muftiu passed away in 2019, at the age of 89. The text that we have selected for publication is taken from the novel “SkhrimtarI”, which is taken from lived events and is dedicated to his colleague and close friend, the dissident writer, Kasem Trebeshina.

Continues from last issue

FRAGMENTS FROM THE NOVEL “THE WRITER”

He had smiled lovingly at his friend and then looked at the jury. The president of the court, in support of the criminal procedure, had asked him to tell the truth and he had answered:

– I can only speak the truth!

The chairman started with the questions.

Besnik had responded with a certain arrogance and, among other things, had declared that he did not accept socialist realism as an artistic method, that there was only realism in literature, that the works of Soviet literature, with the exception of those of Gorky, Sholokhov, Mayakovsky and anyone else, they were worthless cards, that there was no contemporary Albanian literature, that Hyseni was a true poet, that his imprisonment was unjust and would be punished by posterity.

The president of the court interrupted him by ringing the bell and warned him:

– Answer only what we ask you! This is not a conference, but a trial.

He had waited arrogantly:

– This is the only way I know how to speak!

It seemed to him that a shiver had gone through the jury, that they had been surprised and that they had felt his strength and justice. The chairman had finished the questions. The hearing was over and Besnik had left the courtroom full of anger. His hands were shaking.

He had not answered Telhai and Mihaili simply, as before the beginning of the trial, but with strictness and nervousness. In those moments, he was sorry that Hyseni had not spoken in court, as was his habit, with nervousness, he had not vented at all, but his words had been few and restrained.

…Lonely there in the cell, shut, pressed and crushed by the thick concrete walls, by the turret with crossed bars, the heavy door, secured from the outside with large latches and padlocks, guarded all around by policemen, he was delving into himself to understand the causes of this dramatic reality, to understand the essence of his own character.

He felt alive inside the pathos he had during the war for liberation and thought that it would never fade until his death that he had given and would always give meaning to his life. Yes, he could not deny that there had been contradictions with the communists, with the comrades with whom he had fought, especially with some of them, who had become completely different from what they had been during the War.

But in these moments he thought that he had magnified some of their shortcomings and that, rather, there had been misunderstandings. He was almost completely convinced that he had devoted his life to communism with Ali and others. He remembered with great desire those events and those people who closely connected him with the Motherland and Socialism and said in an almost exalted voice: “I am a soldier of communism and I will remain so until death!”

He could not remember anything in his life that contradicted these words, and it seemed to him that he had never had them.

Footsteps were heard outside. The log moved. The guard shouted:

– Get out! Money!

Shaking off his thoughts, he left the dungeon and climbed the stairs.

The investigating colonel, a man of forty or so, short, narrow-faced, with sunken eyes, a cold and sharp gaze, a large nose, had a stern and ferocious appearance. He was given the news of Besnik’s arrest, when he was talking in the dungeon with a saboteur, that he had been parachuted and that, soon, he would appear in an open trial.

Sometimes with threats, sometimes with the cleverness of the fox, sometimes with witnesses, he had forced the saboteur to confess his crimes against the state and now he was sure that the trial would be successful, that the defendant would cause a reaction and the majority of the people would welcome his shooting.

As he finished the conversation with him, he came out satisfied, but as he approached the office, he changed. He remembered Besnik’s behavior at Hysen’s trial. He had never suspected that there was a boy in Albania who had such courage and was so foolish, to express himself so freely and with such arrogance. The investigator was convinced that Besnik proudly advertised his views to writers and young people.

…The investigator entered the examination room, sat down at the table and stood with his elbows resting on it, slightly hunched over, and squinting under his brows in a frightening and menacing manner.

Besnik appeared at the door. He entered as if he was not there in the Security office, the police almost did not follow him behind. His eyes looked calm, straight. The color of his face had not changed, he even looked relaxed. There was no sign of fear on his features. This angered the investigator, and as soon as the arrested person stopped in the middle of the room, he sternly ordered him:

– Sit there, mascara!

The arrested person sat next to the table, where they ordered him. He looked at the investigator and waited.

– What did you tell us like that in court?! – The investigator asked fiercely and added

– Open your mouth here, you are brave!

The faithful answered simply:

– What I had written in the testimony here in the investigator. You knew what I was talking about.

The colonel shouted angrily and loudly:

– No, it wasn’t them, mascara! You expanded and embellished them. You say in court that you do not agree with the arrest of the defendant, that his arrest was unjust?! Who are you? Who asks you? Where are we?

– You knew that was my opinion – said the arrested simply.

– Look, looks, handsome! – the investigator revolted even worse. – He remembers that he is on the boulevard and is bragging to his friends like a rooster in manure. Here you are in the investigator. Are you clear?! I lift you from that chair, where you are sitting and move and stick you in that chair there!

He pointed to an iron chair embedded in the cement in the middle of the room and added:

– Here you measure the words like measuring the head with a pen. We will get your permission on what to do. You can see what Hyseni is. He is an adventurer, a vagabond, who betrays his wife and children and disturbs family peace. He is so arrogant that he remembers that he reached the sky with his hand. We will let him write poems that the blood of the martyrs was wasted, according to you; we will also send him to the West on a special plane. Let’s give him currency with us. Now he himself has regretted his foolishness, but it does him no good. I shed a tear like that.

Besnik frowned. When the investigator threatened him, he lowered his head and remained silent without objection. He thought that he should be obedient and that there was no chance to mess up any worse, but he decided to tell him later that he was not afraid of the iron chair. When the investigator told him that Hysen had cried, he was surprised, softened and spoke to him:

– Do you see that he is not an enemy?!

The investigator accused him:

– He lies, has a grudge against writers, revolts and doesn’t see clearly, why do you protect him and encourage him?! You are to blame! The investigator stared at him sternly, as if he had understood his secret intentions, and continued:

– You made the plan yesterday, you were well prepared. You threw it at us. The mascara was talking to us, as if it were Gjergj Dimitrov! Don’t worry; you will be punched in the head for what you did.

He opened the drawer and was taking out a paper to conduct the investigation of the arrested, when a policeman entered and said:

– The minister is looking for you on the phone.

…Left. He went to his office upstairs, picked up the phone and spoke in a soft, sweet voice:

– Order, fellow minister…!

– Did you get Besnik?

– As you order. Now I was asking him.

– What does it say?

– He is not impressed at all that we arrested him and his mind is blown. To me, he seems more dangerous than Hyseni, because he is aware of his path and something grinds inside him. I have certain information that his mouth does not fit comfortably.

– We also consulted with the Central Committee and decided to deport him to Shtyllas. He is wrong that there is no basis to rise against the Party. There, we believe, he will come to his senses.

– As you order, fellow minister – the colonel agreed.

He hung up the phone and went downstairs to the office. From those few words, he realized that the minister was not very angry with Besnik, that’s why his anger disappeared. It was softened by the conviction that those up there looked much deeper into the problem. He entered the interrogation room as if he were a different person. His movements weren’t so jerky, he didn’t look so wild. He sat down at the table, leaned back in his chair and said in a less rude voice:

– We will deport…! I don’t like you…! Llap.

– Good… – agreed Besnik coolly.

His face expressed neither sadness nor shock.

The investigator scolded him:

– You know that you have harmed us a lot. Shame on you. You are from a family of war. You yourself were a partisan. Western radio stations will explode.

– From this point of view, I admit that I made a mistake – said Besniku sincerely.

– So, think for a moment. You are not small. We raised the republic with blood and we defend it with blood, but your head smells. Go! Tomorrow we will start you.

The faithful got up to run away. When he came out, he stopped in the middle of the room and asked him in a soft voice:

– Can I say a word?!

– Yes – the colonel agreed.

– What is your name, please?

– Abaz – He barely answered through his teeth.

Besnik approached the table and spoke to him:

– Comrade Abaz, you should know that I was a communist and I have seen death with my own eyes since I was a child. As in this movable untied wooden chair, as in that immovable, bound iron chair, I am the same.

The investigator and the detainee looked into each other’s eyes without moving their eyelids. Then Colonel Abazi, who understood that these words were a response to the threat that he had made, shuddered and said:

– You have a strong head. Yes, she took you by the neck. Know from me.

The door of the dungeon was pulled back, closed, the latch pushed, and Besnik found himself alone again, between the thick walls, where a little light came from the small turret, between the crossed bars. The white spot of ray reflection was disappearing. Of course, the sun was setting.

He felt himself uneasy. Before, he did not guess that everything happened to him. Now he knew that he would be deported. He wandered into the dungeon trying to imagine life there, but he couldn’t. He had never seen how the internees lived in Albania. It was clear that his life was taking a completely different direction from the previous one.

…He thought that recently the world, the joy of children, seemed to him to be useless for a few moments. He considered many problems of society as idle and called himself a stranger among people. There were times when neither mother, nor the sun, nor all of nature pleased him. He hurried his steps, shocked by these thoughts, when the guard opened the window and asked:

– Why do you move like that?

– Isn’t it forbidden?! – asked the prisoner.

– No…! No…! – answered the guard and closed the window.

The faithful stayed. Thoughts raced through his head.

Now he was between the four walls, away from those things that seemed stale. Away from the people whose noise he once despised. They were up there, above him, in his life and had nothing to do with him. He felt pressure in his chest. He again imagined himself walking like a shadow through the streets of the city and repeating to himself the famous expression: “To live or not to live – That is the question.” He approached the tower and spoke to himself: “I want the sun! I want life! I want to hear voices of free people”!

I got scared. He turned his head so they wouldn’t hear him. Shut up. No one was near him. He was alone between the thick walls, separated from the world, and he was beginning a difficult life. Memorie.al