Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of Zef Luka from Shkodra, who in 1946 escaped from Albania to Greece, where he stayed for several years in the camps of political asylum seekers. His acquaintance with Alush Lleshanaku, training in an American-funded reconnaissance center on the outskirts of Rome, and parachuting down the mountains of Mirdita in 1949. All the vicissitudes of the “saboteur”, which became the horror of the State Security until 1953, where his name and activity for years was shown as in legends in the city of Shkodra and throughout the North of Albania, are made public according to memories that he has left written in the US, where he spent most of his life as a political immigrant until the fall of the communist regime.

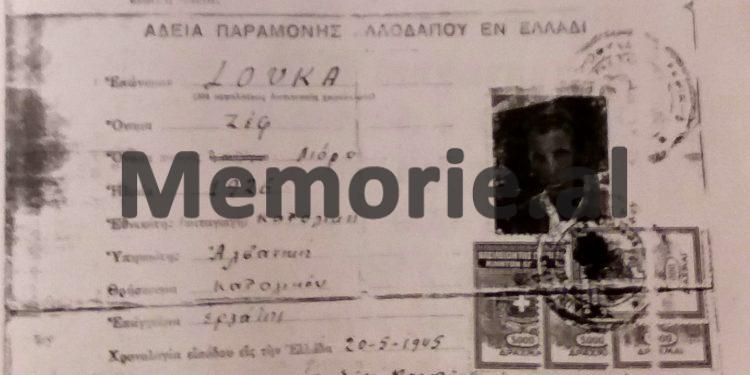

Together with the wild and bitter winter of December 1944 and January ’45, which had not been seen for a long time, most of the Albanians, at the end of those sad years, faced violence and genocide. never heard of. The newly arrived communist regime intensified its crackdown on its political opponents, with arrests, imprisonments, deportations and mass executions, which in a way had begun without ending the war. As a result of these reprisals and the uncertainty that reigned in the country due to the red terror, which became more and more fierce, the escapes of Albanians abroad increased greatly. Even in the South of the country, where the opportunities were a little bigger, there were massive departures towards the border with Greece, where the Communists and the Hellenistic nationalists continued to kill each other, due to the “accounts” still not closed since wartime. Among those Albanians who noticed the danger and the unknown road to the border with the neighboring state, in that icy early January of 1945 were some young people from Shkodra, who performed compulsory military service in a ward on the outskirts of the town of small of Delvina. The main organizer and leader of the group that was undertaking that dangerous adventure, where “playing with the head”, was Zef Luka, a young boy who had not yet turned 20. But were they able to cross the border and what was their future? Who was Zef Luka, what was his past and why did he and his friends embark on that extremely dangerous adventure? For all this, we know the unknown diary of Zef Luka, who after a series of vicissitudes in the camps of political asylum seekers in Greece, Yugoslavia, and Italy, as well as his adventure, wandering for three years in a row as a saboteur in the mountains and In northern Albania, in 1956, he finally settled in the United States, where he lived until a few years ago at a young age. From the diary of Zef Luka, which he has typed, we have selected for publication only a few parts, which he sent us shortly before he passed away to make them public in the press and we are giving them without no changes were made (only subheadings are editorial) and in the Geg dialect, as he wrote and experienced them half a century ago.

Zef Luka’s diary

May 9, 1945

We often talked to Shkodra residents who were soldiers in Delvina to escape (escape), but we did not schedule the day after we expected the situation to change. Hamit Sait Toshi, was from the village of Vilgarë in Ana e Malit, on the border with Yugoslavia. His mother was called File. She had married sisters in Ulcinj as well as a brother. Hamiti was brave and loyal and knew my father when he went shopping to sell something. Hamiti and I had left on Sunday, May 16, 1945, when it was a day of freedom from 1 pm to 8 pm. We will meet you at 1 pm at the Crown of Delvina. Hamiti tells me that Osman Dervishi, who was an officer, is also coming. I said: Hamid, I do not trust Osman. He said: Do you believe in me? Osmani has problems, he has an enemy in the Brigade. This helps us get some weapons out. At the Delvina Crown we had 12 hand grenades hidden. When the army was free-flowing, reconnaissance teams were on patrol not to leave the army. So they wanted to cross the Bistrica Bridge, the pedestrian one, which was heavily guarded before the appeal was made at eight o’clock in the evening. At this time comes Osmani, who had brought his machine gun and the “Beretë” revolver that he gave to Hamid. I was left with 12 hand grenades that I had tied in a handkerchief, so I was left unsatisfied and defenseless. Before I got dressed for Cronus, I told my friend Angjelin Zojzi that: I’m leaving. There I also saw Fofon with friends. I gave her a napoleon of gold that I had after you didn’t think we were going to live in Greece. Fofo started with this, while I continued on my way, crossing the road without a road until we came to the Bistrica Bridge, that is, to the one that was a wooden pedestal, narrow enough for only one man to walk.

Escape from Delvina to Greece

We walked all night, passing Konispol and Bamadat, modern villa villages. It was said that all families had their people in the US helping them. We followed the road and crossed the Bistrica River, tying our hands. A little further on we heard some sheep crowns, we jumped up and asked the shepherd: Is Greece or Albania here? But he did not respond with a single word. You walk down the path, we see that the spies were very far from each other. In a corner of the mountain we see an old woman with a goat, who gave us her son to escort us to the Greek border post. We followed the path on a narrow path that went downhill. On a bush we stopped with a hanger that loaf of bread (eggs) that had given us a piece that we had met by chance on the way. It didn’t take long for a patrol of more than 7 people to climb in our direction. We only saw your feet. If we had not stopped by the hangar, we would have killed them. God saved us. When we approached the post of the Greek border, we said to Osman: You go inside first, if they are communists, kill them, and we are being killed outside. Osman came out to the window of that tower and called us. When I approached the guard at the door, I saw that he had the royal crown of Greece on his hat. When the inside we couldn’t eat because it was our throat, we drank only a little Tamil. Our legs were so bloody that I could barely walk. They put us in three mules and we left Kakavije for Delvinaqi. There was a car road and we were taken to Duljana, where for a week the Greeks and the English interrogated us, from the day we left, until that day.

In Ioannina, for six months

In the surroundings of Ioannina there were barracks without doors and without windows, which were called: Strate Pedon. We slept among the cards that were used for bedding. For the hangar, we didn’t know what was left of the army cauldron. The Korçars, who had fled the 15th Brigade, worked for the state salary and sacrificed there. Ioannina was a beautiful city and brought me the merchandise of Shkodra: the castle, the lake with a small island in between which was called Mesopotamia. The climate was the same as in Shkodra. The city of Ali Pasha Tepelena. The Greeks sang the kanga; Ali Pasha wears the kamena, gives navata. I.e. Ali Pasha sleeps and is not afraid of anyone. There I was called by Jani Dhamanti, who was the mayor of Northern Epirus. Later I felt that he had been killed by Albanian spies. Ali Nivica’s family and brother and cousin also lived there. Seidi Baja, Haki Gaba, Bardhok Gjeta, Xhaferr Luka, Veledin Bobi and his brother, who killed him later when he left the field by the Greeks in Albania. Muço Çaprati from Vlonet and Selim Daci, who was a cell officer of the 15th Assault Brigade in Delvinë, also arrived later. Tahir Reçi, Isuf Luma and Hasan Spata also come there. They collected cigarette butts in the city and sports fields, thawed them and drank them with çibuk. To make me safer, they took us to the Ioannina prison. In Athens and Piraeus, especially on the Red Road (Adhos Kocinja), door-to-door and neighborhood-to-neighborhood fighting was fought between the EDES and the AEM.

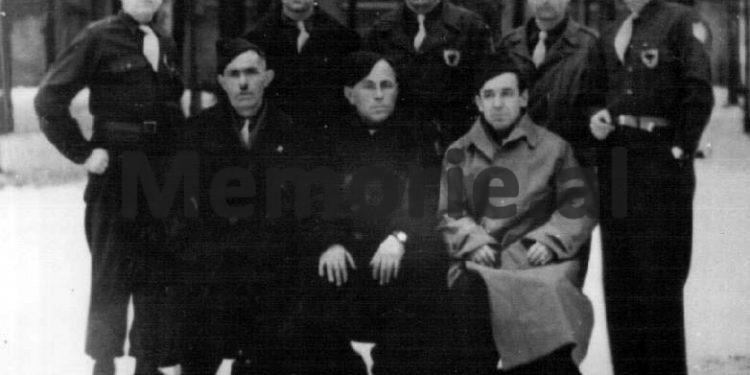

In the camp of Crete and Athens until 1947

From the Iraklion camp in Crete, where we stayed until March 1947, we set off for the Athens Bridge at the Haxhi Qiriakon camp. That camp was located on top of a hill near the Piraeus harbor. The Greek navy was nearby. On the same day, the Greek newspaper “Athens” published a news item stating that in the town of Jera Pjetra in Crete, Greek communists had killed 12 Kosovars. Following the incident, the Greek government withdrew all migrants on the island. Again in March 1947 we are in the Haxhi Qiriakon camp in Piraeus. In a room on the second floor, we were: Muharrem Bajraktari with his son, Fiqëri Dine with son and brother, Hysni Dema, Professor Miftar Spahija, Abaz Ermeni, Tako Baqi and Alush Lleshanaku. General Preng Pervizi had a room with himself a camp and came to us only when he had an inspection. (Perviz lived in the middle of Athens, in the hotel “Bancion”, he stayed in the cafe “Janatis” on Omonia Kantes street in the center of Athens). On the first floor lived Asllan Zeneli with his nephew, Ramazan Cena, Dem Ali Pozhari, Bik Pazari with his brother, Dedë Pepa, Lek Martini and Pal Marku. Dauti, who was from Tirana, performed the duty of a cook. The camp was filled with those who came from Crete. There were also many German women with children who were married to Greeks who had been taken prisoner of war in Germany. For days, Muharrem Bajraktari used to walk around the camp, which was surrounded by small pines, and talk to himself where you could feel him 10 steps away. Hazis Bicaku also lived there with a son, whom the British Intelligence Service was questioning about an officer who had parachuted into Albania to help the communists. But Haziz had surrendered to the Germans. In that camp I met Alush Lleshanaku, who was born in 1913, in the village of Bradashesh in Elbasan, and after graduating from the Normal School in that city, he became a teacher. His father was called Shuaip.

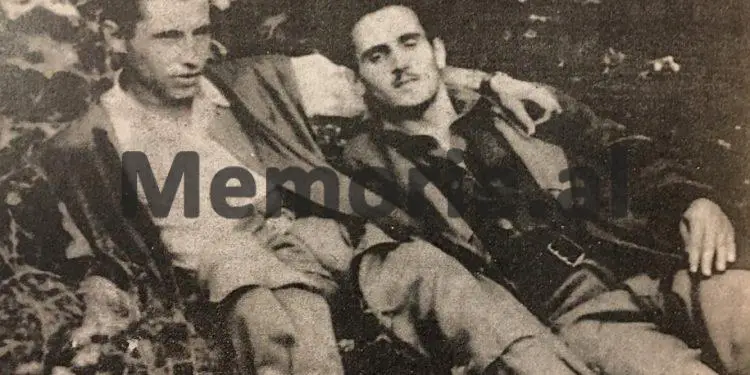

Conversation with Lleshanaku to land in Albania

I told Alushi: “We are sorry for the youth of Shkodra and the communists who were your students, when” Zani i Popullit “in December 1944, wrote that you fell into an ambush and drowned in Dri and that they found your automatic in the trap.” Alushi always led us to do gymnastics. When the police officer came at 9 o’clock, you presented a small list of young people, together with Alushi, to give us permission to go and be left at sea. One day on the beach, Alushi tells me: “Zef, if I had to work in Albania with a parachute, would you come with me?” How come Alush, I answer, we all waited that day, and I promised him. One day I ask him: Alush, what did you do to Enver Hoxha with him? He told me: “You had to put him in a cage and walk all over Albania, but not kill him so that they could see their mistake.”

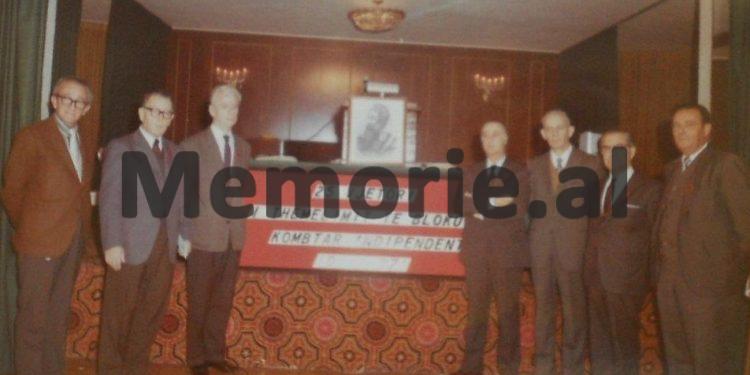

At the Santa Fara camp in Italy

March 1949

With a Greek transport ship we depart from Piraeus to Bari (Italy), to the Iro Santa Fara camp. As soon as we arrived, they provided us with an index card and a book check. At this time, Eduart Liço comes from Romet and takes pictures of us in the camp. This was sent by the Independent National Bloc. It was a transit camp that included: the “Free Albania” Committee, as well as the National Independent Bloc, which was outside the committee. These attracted groups of volunteers who were sent to Albania. The first group was that of Et’hem Chako, the third who was captured alive. Later, they were killed one after the other in Llogora on the Albanian coast. Later, Hamit Toshi (Saiti) told me that he was going to Albania voluntarily, but without Osman Dervishi. “Yes you,” he told me. I replied: I am with Alush Lleshanaku because I promised him that in Greece. This is how the three friends we had escaped from the Greeks were harmed. Osman Dervishi emigrated to Australia, while Besim Kusi, in the camp, had a room of his own and worked as a tailor. One day he called me and said: “Zef, I felt you wanted to go to Albania” ?! When I said, “Yes,” he replied, “Don’t be fooled,” and he told me the story with the miller who put on the general’s clothes and was killed first in the war. When he was on the verge of death, two soldiers who were nearby said, “The bullet hit them in the head.” Mullisi, giving up the ghost, said: “The one who stayed at the mill was the leader”.

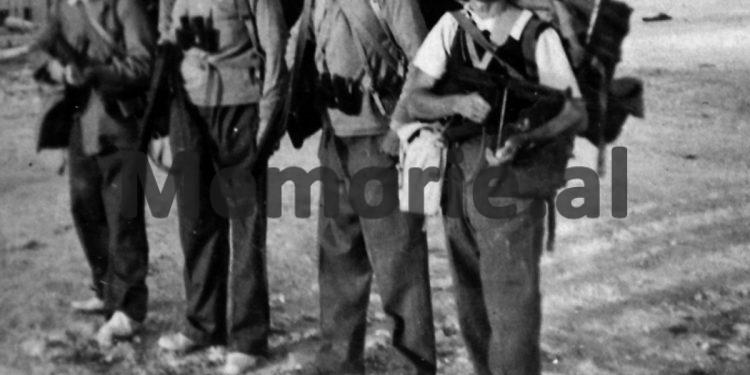

Military training at the Monte Masala camp

The camp doorkeeper informs me that a person was looking for me at the door. When I go out, I see a person in a black car, a watch and a thick gold bracelet. He asks me: “What’s your name?”, I say, Zef Luka. He told me: “Tell your friends to come to the ‘Delle Nacioni’ hotel in Via Lungo Mare Bari.” As we went there, they shot us in a hall, they called our names and gave us all 40 thousand lire. As soon as it got dark, they put us in a truck and drove straight to Golfo di Taranto, a military fort in Monte Masala. The truck was accompanied from behind by a person called Conte Carpio. At this meeting, Pal Mark of Puke, though I called him, did not come. In Monte Mesla we found: Gjon Gjinaj, Pashko Letaj, Kol Çuni, Kol Bib Mirakaj, Alush Lleshanaku and Xhevdet Blloshmi. The group of Mirdita and Shkodra consisted of Kol Çuni, Gjon Gjinaj, Pjetër Gjoci, Bardhok Gjeta, Ndue Frisku, Mirash Marku, Nikoll Marku, Pashko Letaj, and Zef Luka. The group from Elbasan consisted of Alush Lleshanaku, Halil Hoxha, Rexhep Kaso, Zenel Cela, Nuri Plaka, Abedin Xhango, and the third group of the same district from Xhevdet Blloshmi, Shyqëri Biçaku, Isa Kallo, and Kamber Alla. Kol Çuni was qualified for radio, as in German times he had served as a radio operator. But Alush Lleshanaku also taught radio. He taught us how to parachute and how to shoot a gun. In December 1949, we were dressed as sailors and taken from Monte Mesala-Taranto by bus to Rome, to Frascati, Via Violeta, Villa Rossa. Ismail Vërlaci, Gjon Marka Gjoni, Ndue Gjo Marku, Lin Shkreli, Xhaferr Deva and Ernest Koliqi came here once a week. The first group to fall in Albania was that of Mirdita and Shkodra. One day Ernest Koliqi called me separately and said: “I know your father and when I found him, I have nothing to say to him. If you don’t feel able to go, tell me to stop here and get a scholarship to the school. ” I said: No because I have given the floor to Alushi since Greece. Luigj Ferri was in charge of the groups. One day I laughed at him and asked, “Why don’t you let me parachute, what should I do?” And if you laugh, he tells me, “Come and tell me.”

continues tomorrow

Zef Luka’s activity in the archives of the State Security

Zef Luka’s activity and anti-communist activity in Albania is not only reflected in the pages of his diary, but he has also been documented in many numerous archival reports and materials of the State Security, which followed him step by step. His anti-communist activities have also been featured in several books by former State Security officers and senior officials, such as Mark Dodani (“The Silent Front”), Themi Bare (“Provocations, Conspiracy, Failures”), Rakip Beqaj, (“The Enemy Activity of the Albanian Catholic Clergy, 1943-1971”), etc., published before the 1990s, during the communist regime of Enver Hoxha. According to Injac Saraçi from Shkodra (who also prefaced Zef Luka’s memoirs) in a document from the archives of the Ministry of Interior (File 51, Year 1949, p. 109), among other things, it is written: “You are afraid that when to land in Albania, groups of saboteurs could be killed by the people and its Security Forces, said Gjon Gjinaj, from the Vatican various exponents came to give them courage before leaving. Thus, Gjon Gjinaj emphasized: “The day before, on December 27, 1949, the Italian officer of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Karobi, came, accompanied by a Vatican priest, who blessed us so that God would save us from every evil. On December 28 of that year, the saboteur group led by Gjon Gjinaj was preparing to leave for Albania, accompanied by Karobi, De Angelo and three pilots. At the time of departure, the group had met with an American who had talked to Karobi, Gjon Gjinaj and Kol Çuni. Explaining how they were thrown on Albanian soil, saboteur Gjon Gjinaj explained: “We left Rome for Bari. When we duel from Shkodra, Karobi told us: “Get ready. “When the green light comes on, you have to jump.” So we started jumping one after the other: the first Pashko Letaj, the second Ndue Frisku, the third Kole Çuni, the fourth Zef Luka, the fifth Pjetër Gjoci, the sixth Mirash Marku, the seventh Bardhok Gjeta, the eighth Nikoll Nika and. We had landed in the forests of Komi, in the province of Mirdita”.

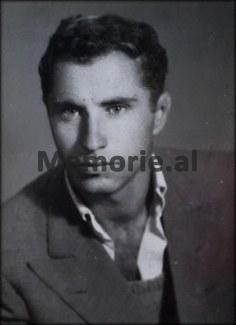

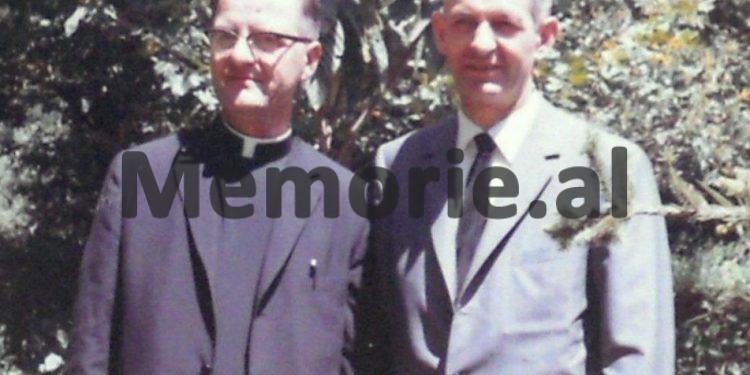

Who is Zef Luka?

From the Jesuit College to refugee camps in Greece and Italy

The author of these memoirs, Zef Luka, was born in 1926 in an old Shkodra merchant family, where his father, Loroja, and uncle, Ludovik, were known as ardent supporters of Luigj Gurakuqi. Zefi was educated in the religious colleges of the Franciscans and Jesuits in his hometown, and just a few months after the end of the war, on March 8, 1945, he was called up for compulsory military service in the southern town of Delvina… Dissatisfied with the newly arrived communist regime, Zefi and some of his comrades, mostly from Shkodra, organized an escape to Greece. In the Hellenic state, he and his comrades initially faced a miserable life in political refugee camps, from which they occasionally fled, doing other hard work to earn something. During that time, when Zefi stayed in the camps of political asylum seekers in Greece, he also met many Albanians, well-known anti-communist exponents. One of them was Alush Lleshanaku, who entered and left with secret missions in Albania. In March 1949, Zefi left Greece and settled in Italy, where he was given the opportunity to pursue higher education. According to Lleshanaku, Zefi joined the ranks of Albanians, who were trained by foreign intelligence in several training centers, and on December 26, 1949, along with nine other Albanians, he parachuted into the mountains of Mirdita. For two years, he and his comrades wandered through the mountains under the constant pursuit of State Security and pursuit forces, trying to organize an armed resistance to the communist regime in force. During those years, in the whole city of Shkodra, the name of Zef Luka became a legend. From that time on, but also many years later, it was said that he had several times managed to break into his home in the city, under the noses of the Security people who were following him on foot. On August 20, 1951, Zefi and several other comrades were forced to cross into Yugoslavia, where he was arrested by the UDB for his anti-communist activities and in defense of the national flag. After suffering some time in prison, in June ’52 he was interned in Sabaç. On October 5, 1954, after being released from exile, Zefi returned to Italy, where he remained until 1956 when he was granted the right to immigrate to the United States. From that year, Zefi lived and worked in Cleveland, Ohio, where he wrote his memoirs about that distant time filled with endless vicissitudes./Memorie.al