By Ahmet Bushati

Part fifty-seven

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

For no more than three months, in the wonderful camp of Berat

Matish Çefa, one of my best friends then and later, had been brought to that camp, the prison of Vlona. He had been arrested in 1950, in a village in Lushnja, where, together with his sister, he was serving as a teacher. If I were asked to give the name of a person who had been the most enthusiastic about his imprisonment, without a doubt I would single out that of Matish Çefa, and also, if there was a person who, without exception, knew and loved a prison like that of Vlona, in this case, it would again be the prisoner Matish Çefa. There were countless peasant prisoners with their shortened names, such as “Xake” and “Zaçe”, “Lipe”, “Muço”, “Nase”

“Bame” etc., most of whom were from the areas of Vlona and Mallakastra, all of whom, like Tishi himself, were prisoners with whom he would spend the most time and with whom he would also get to know and get to know us.

In prison, so to speak, Tishi had found himself. He felt quite comfortable there and, frankly, he did not want to leave it, not to mention having served enough years to justify his claim to be an anti-communist and a good Albanian. So, I, knowing that Tishi had been imprisoned two or three years after me, to tease him, would ask him ironically: “Tishi, how many years in prison did you serve?” and Tishi, with his mouth open as he went from one corner to the other, would answer me, waving his outstretched hand towards me: “Hey, Ahmet Bushati, you should know that I am not leaving here without you, even if it takes a year”!

On one of my last days, I would ask Tishi: “Tishi, now I am asking you seriously, would you want to be released after serving so many years in prison, as you have done so far”? And Tishi, more seriously than ever before, would answer me: “If I swear to you, Ahmet, that without serving at least two or three more years, I do not want to be released.” As other students in that camp, besides those from Shkodra that we have had the opportunity to mention, we also had the names of Tanush Frashëri and Vili Hysenbegasi, from Korçë, the brothers, Besnik and Reshat Krypës, as well as Klito Lames, from Vloë, Myrteza Baboçi from Gjinokastret, whom we will affectionately call “Baboç”!

From Vloë was also another student, Agim Bino, an honest and very determined boy, who had been arrested while trying to escape to Yugoslavia, by swimming across Lake Shkodra. This Agim’s sister was the wife of Delo Balili, one of Mehmet Shehu’s two deputy ministers. When Delo Balili came to command the camp, he would send an officer to bring Agim to meet him and he (Agim) for his part would refuse to meet with him, in the most categorical way, as a communist and a “Security” officer, who was his brother-in-law.

The stork “Sahip Bey”, friend of all prisoners!

In that camp of Shtyllas, we would finally have a stork, who, as they hatch late in the summer, had neither the age nor the strength to migrate with other storks before autumn, and thus remained under the loving protection of all the prisoners of the camp. Everyone loved that stork and called him “Sahip Bey”, baptized so affectionately by Dr. Isufi, who every evening would take him to his small room, next to the infirmary, and feed him like a child, often with a boiled egg, so precious for the possibilities of a camp. As long as the prisoners would stay inside the camp, Sahip Bey would not leave him. When in the morning, when we would leave for work, “Sahip Bey” would be put in charge of us, so that with flights and short breaks, he would constantly lead us all the way.

While the prisoners were working, “Sahip Bey” would move from one brigade to another and at the end of the working day, he would return to the camp with us, not to leave until the next day, when he would again accompany the prisoners to work. That stork was so accustomed to the closed life of the prisoners and, in their company, that he would never feel in himself the instinct of his kind, for a free and wandering life. To everyone’s regret, one day Sahip Bey would mysteriously break one of his legs. On that occasion, the prisoners would ask with pain: “Who broke Sahip Bey’s leg”?! But the author of that cruel crime would never be found alive!

Doctor Isufi would be very worried about his friend’s damaged leg and would seriously do what a surgeon would do for an injured loved one. Day and night he would treat “Sahip Bey’s” leg in his room and occasionally change the bandages. Eventually “Sahip Bey” could not live any longer and Dr. Isufi, moved as he was by his untimely loss, would dedicate a long “elegy” to “Sahip Bey” with moving notes, inspired by his deep sorrow, and in which case, with intelligence and talent, he had managed to combine the pain for the stork with the pain for the people, hinting that just as “Sahip Bey” lost his life, a people, undeservedly, had lost their freedom!

Around mid-September, as if following a decision made by the political prisoners, all the camp spies who wanted to beat or kill their acquaintances were “picked up” during the free time of an afternoon. And it happened that one afternoon, after the prisoners had returned from work, several dozen camp spies were beaten or killed in a concentrated action. It was also funny to see the prisoners – “assassins”, who, with a stick or knife in their hands – (the knives were secretly made from large nails, with which they were fastened to their armor) – run after the spies, who, in a panic, tried to escape by dodging through the crowd of other prisoners, many of whom would deliberately block their way.

A prisoner who had not actually been a spy, but a former communist, was hit on the head with a large brick by a large Tropojan, but who nevertheless escaped with his life. A few spies escaped without being beaten or stabbed, who at that time had not been shot outside, and I remember that one of them, who had once been an officer and later the chairman of the council, a rather well-groomed man from the Berat district, with a mustache that extended to the sides with a point, and who even in the summer would not take off the military boots of the former officer from his feet, and who in the evening, accompanied by two permanent people, would run up and down the camp square dozens of times. For such a haughty, not proud attitude, – as he himself must have believed – he would have removed everyone’s warning, to his detriment.

The day after the “action”, Sunday morning, while I was walking quickly through the camp yard, for some reason, the sight of this man cooking something outside made me say to myself: “It seems this man wasn’t on the list”! And to my surprise, at that very moment, a tall, thin villager came up behind him, who, with a short, thick stick in his hand, began to hit him hard and fast on the head, quickly knocking him unconscious to the ground. Those of us who happened to be there thought that he had been taken for a ride, and someone even said that the person who beat him had been a fellow villager of his, with whom he had a score to settle. Finally, even though we weren’t interested in his fate, we would accidentally hear that the man hadn’t died, that he was still in the hospital, and we thought about it all.

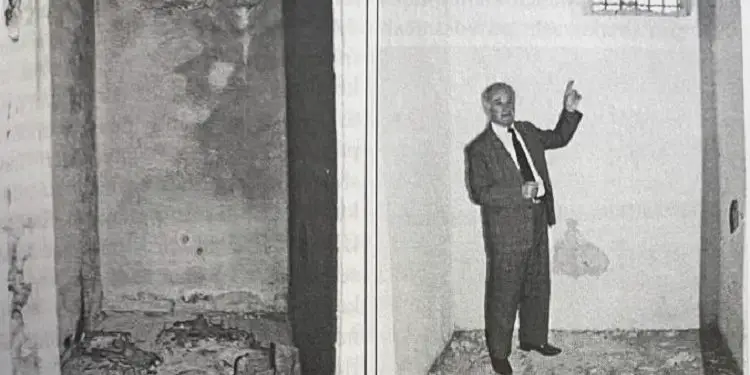

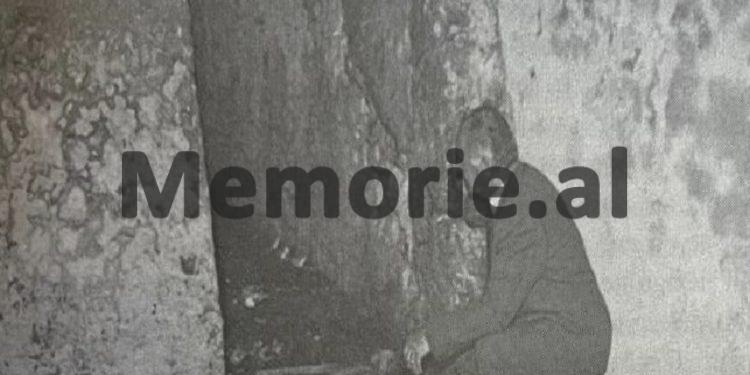

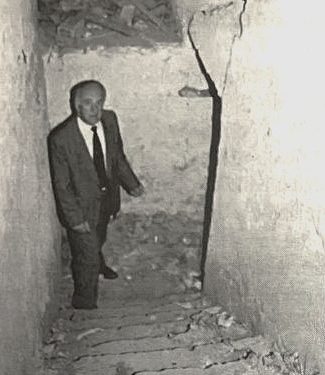

The beatings of the spies, the discovery by the command of a tunnel that a group of prisoners had dug inside the bunker, right under their sleeping place, as well as the courageous opposition by some prisoners to Lieutenant Adem -who during those days had been brought to us once as a commissar- caused a fairly unbridled terror to erupt in the camp. Going outside the bunker was absolutely forbidden. With the exception of fifteen to twenty seriously ill patients in the infirmary, the other sick people could not rest in the camp. If a sick person stayed in the camp on his own initiative, a tree would surely fall on him. They also took away some of the dishes we had been cooking with for four years in the camps, as well as other containers where we kept food, so much so that some prisoners, not knowing where to put the water, would throw it in their boots and, on a rainy day, go to work barefoot.

Completing the years of imprisonment by a political prisoner during those days did not mean that he would certainly make his way home. There were some cases when prisoners, on the day of their release, went straight into exile. For the perpetrators of the beatings of the spies, those who had attempted to open a tunnel, as well as for those who had opposed Lieutenant Adem, small tin dungeons were quickly constructed, no more than 70 centimeters high, inside which those imprisoned would suffocate like pigs from the heat and thirst. Among others, several of our friends were also put inside those dungeons, such as Mark Prela, a member of our board, Abdulla Nela, Koço, etc. That terror on the eve of my release would cause us to lose all the bronze and ceramic objects that we had found deep in the ground during the works to open the canal and that we had been guarding very carefully for months.

The ceramic objects, often painted, would consist of cups and bowls of various sizes and shapes, which for more than two thousand years had miraculously preserved their dark color and bright glaze. We had found and preserved clasps (brooches) and other ornaments made of bronze, as well as many coins, also made of bronze. One of the most precious objects would be a gold earring, as well as another, a glass-like object, in a wonderful sky color. Finally, in miniature, we would have cast in bronze the figure of a warrior holding a sword in one hand, which symbolized protection and war, and in the other an ear of grain, which of course symbolized life and peace.

We had planned and even designated the location so that on the day of my release, my fellow prisoners would take those objects with them when they went to work and hide them at their place of work, under a cart of dirt. After they returned to the camp, I was released, and at night, I would go to get them. Unfortunately, this would not be possible, because those very valuable objects, although we had wrapped them up and taken them out onto the roof, to save them from the reprisals of those days, would happen to be caught by some policeman, who during the search must have discovered them and quietly took them for himself.

I was released by the thread of a penny!

During the four years in the camps, I had gained about four months of time, so, to complete the seven years of my sentence, I would not wait for January 20, 1955, but I would be released on September 23, 1954, but as I said above, it was not known whether I would be released or not! As in my opinion and that of my friends in general, there was a greater possibility that I would go into exile, which is what I also informed the country about, Thabit, Thabit Rus, was interned a few days earlier, exactly the day he was completing his prison sentence. The prison command had a designated officer who was responsible for the release of prisoners, and as a rule, the day before, the prisoners who were to be released were informed by him that they should remain in the camp the next day, waiting for the officer in question to bring them a certificate of association, valid as an identity document, until they received their passports.

Since I was not notified of my release until the day before September 23, the chance of being released no longer existed, however, I decided to do my part, not to gain anything, but as a reaction to the despair that my family would experience on that occasion. Since the afternoon of September 22, I separated one by one from all my camp comrades. Including many ordinary prisoners, and especially from some of them, with whom, as it were, brotherly we had shared the difficult life of the camp. When on the morning of my last day – shortly after dawn, the prisoners left for work, the whistle of the duty officer was heard in the camp, notifying the prisoners remaining in the camp to appear for the appeal. A small group of sick old men – completely exhausted – slowly and as if staggering out of the infirmary and took a place on the side of a small canal, next to their infirmary.

The justification that I was serving my sentence that day was completely insufficient for the duty officer, who immediately began to make a big fuss and threaten me a lot for the initiative I had taken. For this, the parole officer was also called, who, although he did not belong to the category of bad officers among us, did not know what would happen to me and, without any bad intention, seemed to be playing with me. Thus, sometimes he would remind me of my origin; “Bushati” and my not good political stance in the camp, and quickly turn back laughing and telling me that; “You are young and you will go home”. When he would repeat this last, the group of sick old men, – most of them our mountain people – still not leaving there, would congratulate the officer, as if with gratitude and regret: “Hey, you have a good mouth”! However unintentional that officer’s play with words was, it once became unbearable for me and towards the end, I said to him angrily: “If you know anything, tell me, whether I am released or not, and nothing else, that’s enough for now”! He left it at that and left as if with a kind of smile on his face.

My case, as it seemed, had not yet received a final answer from the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Tirana, which in those days, apparently, wanted to ask about every prisoner who was serving his sentence. After a while, I was taken out of the camp and, accompanied by a policeman, I was taken to a bricklayer who was a prisoner, who wanted me to prepare mortar for plastering a small reed hut that would serve as a barbershop for the camp policemen. “Since I am serving my sentence today, I will not do any manual work,” I told him, as an ordinary prisoner, and continued: “You can tell these two policemen,” – one who was guarding us, the other the head of the guards, who was still standing there – “so that they can bring you another one in my place,” while he, who was looking at me for the first time in the face, would answer me with regret: “No, brother, the girl is going home, because this work is easy” – and began to prepare the mortar himself.

After lunch, they took me back to the camp and told me to take my belongings out, without telling me whether I would be sent to internment or released! In fact, both prison and internment had, by then, become, so to speak, a thing for us, as we learned who we were, as well as the probability that it would happen, while release, as something not so much for us, as something vague, therefore not very tangible and real, and consequently, not credible, especially given the circumstances that had recently been created and, to be realized, as if it would wait for another time. If I was somehow suffering from a kind of anxiety, which could more likely have been pity for the family, I cannot say that I felt seriously worried, because of the dilemma of home-internment, as I was very prepared for the worst. Maybe I was experiencing that state, which, in order to be properly happy, needed a final communication, whatever it was.

With my luggage on my back, I left the camp that seemed to me to be completely lifeless. They told me to take my luggage outside, somewhere near the large gate of the camp, and to climb the hill myself, where the command was located. At first I was not moving, waiting for the policeman to come, who, according to the rules, was supposed to put handcuffs on my hands and accompany me to the top. The policeman had turned his back on me and, after a few minutes, when he saw that I was still standing there, he spoke to me as if in surprise: “Go up, what are you waiting for”!? I was surprised to see myself with my hands untied and without a policeman by my side, and as I walked up the hill, I occasionally turned my head back to see if the policeman was really coming! After waiting a while in the command corridor, a policeman told me to enter the office of Commander Kamber Halili, where besides him, there was also a man with a large body and face, an employee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Tirana, who, assuming the pose of an important person, would speak to me coldly and, as if in disbelief:

“You must have thought of it, haven’t you?” – while Kamber Halili, like a sorrowful woman and with the smile of a good man, was writing me the certificate of release. I first shook hands with Kamber Halili and then with the other one and left. Only then did I realize how unprepared I had been for the release! I was descending the hill, as if unfocused on anything, with an indeterminate feeling that was neither joy nor longing, and perhaps more like an emptiness that still did not allow me to gather my mind properly. I had already been prepared for internment. Many of my fellow prisoners, when I was parting from them, had told me: “Ishalla is going home, but the chances are not. We are sorry for your family, Ahmet, but we know about you”! There would have been prisoners like Isuf Vrioni and others who would have given me orders for the particular internments, with whom they believed I was joining on that occasion.

The idea that I was going home, while my friends were staying inside, no matter how naive it may seem, made me avoid concentrating, both on one occasion and on another, proving that my soul, after seven years in prison, had become its hostage. Seven years of youth, seven years of great suffering, but also of an indescribable patriotic enthusiasm. Seven years without freedom and family, but with friends, without whom I was seeing myself, especially that day, which were enough for me to have no concrete idea of the life that awaited me!

Before throwing the bundle of loot on my back, I looked towards the camp, where I saw no prisoners and nothing. I was walking as if on a lost foot, along the barbed wire fence and about ten or fifteen meters before its end, on my right, I saw for the first time the metal dungeons, placed like a cage in a row, one after the other, inside which dozens of brave boys, convicted of the events we mentioned above, had been burning like in an oven for several days, among whom were some of our friends, such as; Mark Prela, Abdulla Nela, Koço, etc. Without thinking about anything, I dropped the bundle I had on my back to the ground and without even looking at the tall policeman with a machine gun in front of me, who was shouting that; “he would kill me if I didn’t leave immediately”, – I did my thing, calling out as loud as I could: “Mark, Abdulla, Koço, I’m Ahmeti, I’m going, goodbye, goodbye to the others too”.

Hodo Sokoli, my friend, knowing in advance the day of my release, had arranged that on that day, he would come to Shtyllas with food and some loot, where his brother, Brahim, was interned. After he had finished his work, related to what he had brought his brother from Shkodra, he did not leave there, waiting to join me. After we met and hugged like friends who had been friends since childhood, he left for Fier-Shegan, to carry out a small job, before I arrived there, to then continue the road to Shkodra together. After less than an hour, I, like Hodo before me, found a carriage to Fier-Shegan and as we walked a couple of kilometers away, deep in the field, suddenly my eyes vaguely discerned the crowd of prisoners returning from work, a crowd that from a great distance, seemed like a black thing, like a small, compact mass that moved slowly and, as if swaying slightly.

It wouldn’t take more than a moment and in the most spontaneous way, an oil would burst out of me, which for at least three or four minutes, no amount of effort on my part would stop it, just as not even the painful prayers of the two teenagers, the owners of the carriage, who were touched by my condition, had stopped the carriage, and asked me: “What have you done, brother, what have you done, brother”? while I, in silence and despair, seemed to ask myself with wonder and regret: “How was it possible that she took people, a part of whom I had been for years until the morning of that day, and returned without me”?!…Memorie.al