By Prof. Dr. Kaliopi NASKA

Memorie.al / Ismail Qemali are a historical personality with a very rich and extremely complex political activity. This multifaceted activity spans a period of almost 60 years, packed with armed movements, parliamentary struggle, liberation uprisings, and turbulent “tides and ebbs” in which he was a very active participant in the fight, as an ideologist, leader, organizer, and diplomat. His activity and views are manifold. The concepts he held about state-building occupy an important place in his system of views.

To understand the basis of Ismail Qemali’s concepts on the form and administrative structure of the Albanian state, let us take a brief look at his formation and activity as an official in the Turkish administration, where he served for about 35 years.

STATE OFFICIAL IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

He began the chapter of his life as a state official in the administration of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul, where he soon distinguished himself as a person equipped with a broad culture, with deep and constructive erudition. The deepening of his studies in legal sciences and his intelligence all contributed to his rapid entry into the Ottoman administration and performance of various important functions as a governor, as the general secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and even as a state advisor.

During these years of varied state activity, he became familiar with the many sharp and difficult problems that required solutions or at least required a stance to be taken before the state and the public. These concerns, along with his cultural and ideological formation, pushed him to believe that the Ottoman Empire had to emerge from the tense situation in which it was immersed. To get out of this situation, he thought that the only doctrine that would pave the way for a solution was the application of Mithat Pasha’s doctrine, which was the most progressive for Turkey at the time.

The content of this doctrine led Ismail Qemali to connect with Mithat Pasha, who was the leader of the Ottoman liberal movement. In particular, he agreed with the essence of his ideas, which was the conviction that the Ottoman Empire could enter the path of progress and modernization through reforms and not through revolution.

Thus, he thought that the absolute system of the Sultan would be liquidated, which would be replaced by a constitutional regime without eliminating the royal crown, but by limiting the sovereign’s absolute power. He also agreed with the principle of decentralization of state administrative power in favor of the bourgeoisie and, in particular, of the many nationalities of the Empire, which would thus gain the right to provincial self-government within the framework of the Ottoman Empire.

So, as can be seen, Ismail Qemali aimed to achieve provincial self-government for the nationalities through the radical regulation of the Empire, and not by being interested only in the autonomy of one or the other nationality, but for all nationalities simultaneously, through the radical regulation of the Empire. Ismail Qemali not only adopted these ideas but tried to apply them during his career as an official of the Ottoman Empire, and some of them accompanied him in his role as the head of the first national state.

ISMAIL QEMALI’S LIBERAL VIEWS

Ismail Qemali became an enemy of Sultanic absolutism precisely from the perspective of these liberal views. This led him to participate in the drafting of the 1876 Constitution, or in the drafting of several memoranda sent to the Sublime Porte, opposing the Sultan’s absolute policy and exposing the decay of the conservative administrative system. All this activity helped Ismail Qemali understand the mechanism of state administration quite well.

The activity he developed in the Ottoman Empire as its functionary clearly showed that he was an illuminist and reformist activist, representing the interests of the liberal bourgeoisie of all nationalities. The great prestige he enjoyed in Turkey and in high diplomatic, patriotic, and intellectual circles of Europe, his liberal, democratic, and progressive sentiments, made him a well-known figure with authority, but also a dangerous enemy and a target for the anachronistic Ottoman autocracy, with which Ismail Qemali could not agree.

For decades until the end of the 19th century, Ismail Qemali distinguished himself as a militant of the Ottoman democratic-liberal movement, within which he thought the Albanian national issue would also find a solution. But at the beginning of the 20th century, when the Ottoman liberal movement entered the path of Turkish nationalism, which complicated the solution of national issues in the empire, Ismail Qemali, without abandoning his liberal view, detached the Albanian national liberation movement from the Ottoman liberal bourgeois movement and turned it into a separate issue.

With such political preparation and cultural horizon, he quickly became involved in the ranks of the Albanian national movement, actively participating in it, where he distinguished himself as a great politician, diplomat, and statesman, who was imbued with the traditions of the most progressive culture of his time and country, who assimilated everything good that the Albanian liberation movement had with arms and pen, and who followed this movement until its fortunate culmination.

The Albanian nation rightly considers him the main protagonist of the Assembly of Vlora which, on November 28, 1912, declared national independence. Regardless of his origin, due to his long-standing formation, he was molded as a democratic statesman, being elected as the head of the first Albanian government, thus becoming the main leader of the country’s political life in extraordinarily complicated and difficult moments that the reborn Albania went through during the critical period of intervention by the Great Powers and neighboring monarchies, which rushed to annihilate it.

THE FIRST FOUNDATIONS OF THE ALBANIAN STATE

The declaration of independence marked the beginning of a new historical stage that posed new and complicated tasks before the Albanian people and the leaders of the National Movement, who had undertaken the heavy burden of creating the independent state. The head (Chairman) and the government faced great tasks for organizing the state and establishing the state administration, ensuring the international recognition of Albania and its borders that included the areas inhabited by Albanians.

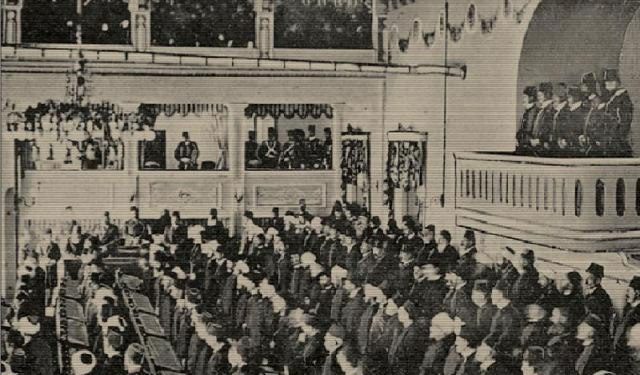

As early as December 1912, measures were taken to lay the first foundations of state organization, and the first legislative acts were approved, which were defined by the decisions of the National Assembly, which included delegates from all regions of Albania and objectively represented the will of the entire nation, becoming the highest organ of the Albanian state, the protector and expression of state sovereignty.

Therefore, its decisions had the value of constitutional laws that sanctioned the will of the Albanian people to secede from the Ottoman Empire and to create an independent state. Another body elected by the Assembly was the Pleqësi (Elders’ Council), whose competencies were not explicitly defined by the National Assembly, but the latter accepted the view that the Pleqësi was not a parliament or senate and did not have the right to dismiss ministers, but should be considered as a body for consultation and control over the government.

A KING WHO DOES NOT RULE

The National Assembly limited itself to the Declaration of Independence and the election of the government and the Pleqësi. It did not consider the issue of the form of government of the Albanian state. But it is known that the overwhelming majority of Renaissance activists, including the representatives who participated in the Vlora Assembly, thought that Albania should be born as a monarchical state, because they rightly or wrongly saw Monarchy, just as all the founders of the Balkan states, and even European ones, had seen it, as the consolidation of the national state.

In fact, all Balkan states were Monarchies. But the political personalities of the time differed in how they conceived Monarchy, absolute or parliamentary. Precisely in this context, Ismail Qemali appears with the most progressive views, not only for Albania but also for the Balkans, as he was for a constitutional Monarchy where, according to the principle, when power would be in the hands of the people’s representatives, the King would have the function of the head of state who “would reign but not rule.”

FOR THE ARRIVAL OF PRINCE WIED

His opinion was supported by government representatives and found approval in the government meeting, where the program of the commission that would present the Albanians’ requests to the Great Powers was approved. One of these requests specified the establishment of a constitutional monarchy in Albania with a king from European countries. Despite the presentation made by the Albanian commission to the Conference of Ambassadors in London, it did not make any official determination of the form of government.

It only specified that Albania was declared a sovereign, autonomous, and hereditary principality with a prince appointed by the Great Powers. Ismail Qemali and the patriots saw the appointment of a European king as the personification of rapid economic, political, and social development of the country. Therefore, Ismail Qemali, in his capacity as Chairman, insisted with the powers to expedite the appointment of the Prince, who, according to them, would ensure the stability of the national government and eliminate all internal difficulties, ensuring a new development for the country.

These were the reasons why Ismail Qemali and other patriots would value the arrival of Prince Wied in Albania as a positive factor that would influence the realization of national aspirations and lead the country towards national unity. But the development of events showed that Prince Wied could not be expected to act in Albania’s interests when these conflicted with the will of the Great Powers.

THE ADMINISTRATION, COURTS, GENDARMERIE…

Since the Conference of Ambassadors did not make a determination on the form of the state, the independent Albanian state was created as a state with a parliamentary system, the role of which was fulfilled by the National Assembly, which, even after ending its work, maintained its prerogatives as the highest organ of the state. But in the existing conditions, the National Assembly did not have the effective possibility to convene, and in reality, the government of Ismail Qemali, based on the power delegated to it by the Assembly, concentrated all state power in its hands, carrying out both administrative and legislative activity.

Although this activity was more limited due to the circumstances of the Balkan War, it is precisely these exceptional circumstances that explain why Ismail Qemali was unable to fully implement the principles of constitutional action, by not granting the Pleqësi the right to a deliberative vote, as the constitutional principle requires, and limiting this right only to a consultative vote.

Thus, Albania, from the end of 1912, had the elements of an independent state organization, such as the existence of a determined population in a determined territory and a public power that directs it. Ismail Qemali, in order to put the new Albanian state on organized foundations, together with the government took measures for the establishment of organizational structures, such as the establishment of the state administration, the organization of courts, the gendarmerie, the police, etc.

ALBANIA TO BE DIVIDED INTO THREE CANTONS

He had expressed his ideas about the method of organizing the country before the declaration of independence. At that time, foreseeing the difficulties that would be encountered in organizing a centralized power, he had expressed the opinion for the division of Albania into cantons, following the example of Switzerland. But on this issue, he showed an incorrect viewpoint, which stemmed from the fact that, having lived for decades away from Albania, he did not know the country well and gave great importance to the weight exerted on the internal life of the Albanian people by its regional and religious differences.

In this, the existence of local autonomies in some regions that had existed, and which the Ottoman Empire had not been able to destroy, seems to have influenced him. He thought these autonomies could be exploited for the benefit of the modern state. He retained this idea even after the declaration of independence and tried to reflect it in the drafting of the Provisional Statute (Kanuni i Përtashëm) of the civil administration of the Albanian state. According to Ismail Qemali, Albania would be divided into three cantons, with capitals Shkodra, Durrës, and Vlora, which would be governed respectively by Preng Bibë Doda, Esat Pasha Toptani, and Ismail Qemali.

He reinforced his cantonal idea, especially in the speech he gave at the popular rally in Vlora on October 21, 1913, where he emphasized that every region (canton) should be governed according to its specific characteristics. “From this,” he stressed, “it follows that the Lab will be Lab, the Geg will be Geg, and the Tosk will be Tosk, and each will work only for Labëria, for Gegëria, and Toskëria, but all with Albanian ideals will work as Albanians and will be killed as Albanians for Albania, drawing strength from the progress of their own region.”

NO TO THE DIVISION OF ALBANIA INTO CANTONS

But the regional specificities that Ismail Qemali provided were not a reason for division into cantons. In some Western countries, there was some degree of local administrative autonomy, but this had nothing to do with the cantons in Switzerland, which were divided according to linguistic, religious, and local specificities. It is known that Albania within the borders of 1913 consisted, in its overwhelming majority, of a simple Albanian population. Therefore, such a system applied in a state with a heterogeneous national composition like Switzerland could not be applied in a state with such ethnic homogeneity as Albania.

Such a circumstance was not unknown to Ismail Qemali. The proposal made by him for the division of Albania into cantons at this time did not align with the task facing the Albanian state, for the strengthening of its administration and centralization. This was not the way to preserve the national “unity” of Albania and its independence. As time showed even then, Albania’s independence could only be secured in the struggle against separatism, which had been sown by feudal cliques supported by the Great Powers and neighboring states. The disappearance of separatist powers and the establishment of centralized governance was the only way for the economic, social, and political progress of Albania. National interests required it to remain one and undivided, even from an administrative point of view.

This is the reason why his idea was not accepted by many government members, including distinguished patriots, and even his close collaborators, such as Luigj Gurakuqi, Petro Poga, Pandeli Cale, etc. They opposed the division of the country into cantons, calling it a “harmful measure for the unity and survival of our nation.”

They rightly emphasized that in order to strengthen the nation, the division between regions should not be deepened; on the contrary, they should be closely connected to each other and administered from a single center. Ismail Qemali took the criticisms made on this issue into account, and even more so, showed that he was not fully convinced of the superiority of cantonal organization for the country’s conditions. Consequently, his cantonal idea was not included in the “Provisional Statute” (Kanuni i Përtashëm) and was not reflected in the laws that the Vlora government began to proclaim and implement.

THE “PROVISIONAL STATUTE” AND THE NEW LAWS

After many discussions were held on the directions that the administration’s organization would take, the proclamation of the “Provisional Statute” (Kanuni i Përtashëm), which we mentioned above, by the Provisional Government in November 1913, was of particular importance, as was the law defining the new administrative division of the country. The Statute would regulate in detail the administrative division and the competencies of the local bodies. This determined a normative act based on the principle of administrative centralization of the country according to the model of European states.

At its foundation was placed the principle of creating a central administration. According to the Statute, Albania was divided into prefectures, which represented the highest local unit, and these, in turn, into sub-prefectures and regions. From the norms contained in the Statute, it emerged that power in Albania would be concentrated in the hands of the Vlora Government. The laws issued by the government for the organization of the local administration levels constituted an important step since they differed from the Turkish imperial administration, due to the fact that they gave the Albanian state, to some extent, the physiognomy of a modern state in form and content with a centralized progressive administration.

Such laws that differed from previous legislation were, for example; the exclusion of state organs’ intervention in the affairs of justice, or the partial separation of state institutions from religious ones. New acts were also issued, such as on the method of inheritance division, etc. Despite the fact that the law on territorial administrative division was not fully implemented, because the Vlora Government remained in power only two months after its approval, it represented a serious effort to establish a local administration based on relatively democratic criteria, insofar as the functioning of elected bodies, albeit with limited competencies, was foreseen.

To this effort by the Chairman and his government to provide the country with suitable and modern structures, other measures must be added, such as designating the Albanian language as the official language, the opening of schools, etc. In conclusion, we can say that the contribution made by Ismail Qemali and the government in approving the important acts of the Statute for the organization of the central state apparatus and the organization of local administration bodies, helped complete the full physiognomy of the organized and independent Albanian state, both at the center and at the local level. He and his government laid new foundations for local administration in the country. / Memorie.al

![“They have given her [the permission], but if possible, they should revoke it, as I believe it shouldn’t have been granted. I don’t know what she’s up to now…” / Enver Hoxha’s letter uncovered regarding a martyr’s mother seeking to visit Turkey.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Dok-1-350x250.jpg)