By Feti TUNUZLIU

ACADEMICIAN GAZMEND ZAJMI’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE DRAFT OF SOURCE ACTS FOR THE SOVEREIGNTY AND INDEPENDENCE OF KOSOVO –

Memorie.al / Academician Gazmend Zajmi belongs to the cream of the outstanding historical, national, scientific and university figures of Kosovo and abroad, of the second half of the 20th century, as a prominent lawyer and political scientist who left behind a precious national and state-building heritage. Coming from a Gjakova family with patriotic traditions, academician Zajmi was born in Krumë (Albania) 86 years ago, on June 20, 1936, and passed away at the age of 59, on March 10, 1995. He completed primary and secondary school in Prizren, while in Belgrade he graduated and obtained his master’s degree at the Faculty of Law and his doctorate at the Faculty of Political Sciences.

He held a range of positions. Among them, we highlight: President of the Kosovo Academy of Sciences and Arts (ASHAK); Rector of the University of Prishtina, Head of the Department of Political Science and Professor at the Faculty of Law of the University of Pristina; Judge and President of the District Court in Prizren, President of the Association of Universities of Yugoslavia; and member of the European Academy of Sciences in Salzburg (Austria).

In addition to his great contribution, he will be remembered for his dismissal from the position of Rector of the University of Prishtina in 1981 and his exclusion from the professorship of Law due to his failure to distance himself from the demands of students and pupils or, “from the Albanian anti-Yugoslav movement”, as it was said in Serbian journalism, as well as for his exclusion from the Communist League of Yugoslavia in 1984, because – having come into conflict with the ‘Document of Ideo-Political Differentiation’. Meanwhile, it was stated: “The action of ideological and political differentiation represents political sadism”! Furthermore, he will be remembered as an opponent of the termination of the Protocol of Cooperation between the University of Pristina and the University of Tirana, when he was Rector and co-initiator, co-author and signatory of the “Appeal 215 of Albanian Intellectuals”, which, among other things, also demanded the solution of political and national problems in Kosovo society.

Marking this anniversary, let us emphasize that academician Esat Stavileci (1942-2015), called academician Zajmi; “architect of political and legal thought, for Kosovo and on an international scale”. He claimed that; “no one better than him has argued the issue of Kosovo’s independence”. Therefore, “we have the views of scholar Gazmend Zajmi as a support”, for the “main arguments in favor of Kosovo’s independence”, he said. And these views and arguments, Prof. Stavileci summarized them in his authorial book: “The Kosovo Issue, in the Work of Gazmend Zajmi” (1997).

The work and imagery permeated with elaborate academic ideas, which shed light on political, legal, historical and national processes, the situation of national minorities and the position of languages and the autonomy of Yugoslav federalism, distinguish Prof. Zajmi as a thinker and visionary. Separately or in a broader framework, these ideas took their place in his creative opus, in: works, monographs, studies, articles, lectures, presentations, discussions and lectures. All together they reveal him as a scholar of his kind, second to none in constitutional law and the political system in Kosovo, which had become a hostage to reading and insomnia.

Otherwise, he had addressed the social, political and legal aspects of language equality in Kosovo, in the topic of his magistracy (1971) and the constitutional-legal protection and treatment of the languages of national minorities in Europe during the two world wars, in the topic of his doctoral thesis (1972). Therefore, his work is a point of reference for researchers. We will refer to them in the following, putting them in quotation marks.

Honoring the memory of Prof. Zajmi, let us say that he was among the direct protagonists of the dramatic political and constitutional developments, since the sensational year of 1968. Appreciated for his kindness and positive sense, he grasped things very quickly and was the voice that critically and with excessive courage revealed political demands: for self-determination, for the status of the Republic for Kosovo, for the status of the nation, for the Albanians and for the direct connection between Kosovo and the Federation, to be equal to the other republics. It goes without saying that these demands, which shocked many in the former Yugoslavia and caused confusion in neighboring countries, were substantiated with convincing scientific and historical evidence.

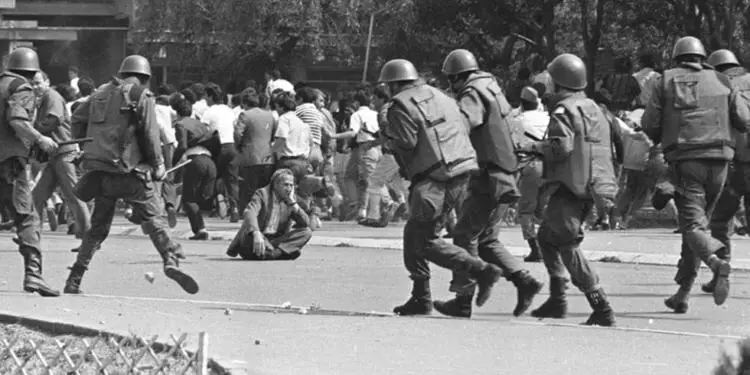

While disclosing ideas that deserve special attention, he took as a trigger the tangible social and political realities in Kosovo and the former Yugoslavia, from before the Second World War, until the decades of communism. With Prof. Zajmin, were listed: Fehmi Agani, Ali Hadri, Bardhyl Çaushi, Hajredin Hoxha, Syrja Pupovci, Ramadan Vraniqi, Dervish Rozhaja, Rezak Shala, etc. But, after the outright disregard of such demands by the Serbian and Yugoslav government and party authorities, Albanian students and pupils reflected, more clearly than ever. They exerted all their invincible courage and energy and organized demonstrations throughout Kosovo cities, but were ruthlessly suppressed by state violence.

The above political demands, which this resourceful scholar pondered, had a rapid positive effect. Here are some achievements: in 1969, the Constitutional Law for Kosovo was adopted (replacing the Statute); the name Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, (replacing it; “Kosovo and Metohia”); the Albanian language was legalized as an official language, the use of the national flag was allowed; in 1970, the University of Prishtina was founded. In 1971, constitutional changes expanded and equalized Kosovo with other republics, especially in economic policy. In 1972, amendments to the Constitutional Law of Kosovo strengthened the constitutional position of Kosovo in the federation. In 1974, the Constitution of the Autonomous Socialist Province of Kosovo was adopted, in 1975; the ASHAK (Kosovo Academy of Sciences and Arts) was founded.

Regarding these achievements, the professor of constitutional law and political system, had a negative stance on the thesis that; – “Kosovo is part of Serbia”. Kosovo was not part of Serbia, but as a political-territorial identity of its own, with its own constitution, it was a constitutive unit – a federal unit of the multinational Federation of Yugoslavia and only as such, based on the constitutional presumption of the common interest of Kosovo and Serbia, it was; “corpus seperatum”, with its own political and constitutional sovereignty, was also within Serbia”, he explained. In function of this concept, his scientific credo brought to the attention of the public its original legal-historical argument, claiming that: “The constitutive basis for the establishment of Kosovo, within the Republic of Serbia, is the Prizren Resolution of 1945, which as such was sent with the Constitutional Declaration of Kosovo, according to the principle; “Lex posterior derogate lex prior”.

But, the year 1981 came. Demonstrations reappeared in Kosovo. And with a dynamic and energetic character, Prof. Gazmendi supported the youth, for their determination. The demands were repeated: “Kosovo Republic”, “Republic, now with hatred, now with war”, etc. Unfortunately, these demonstrations would also be brutally suppressed by the bloody Serbian-Yugoslav state. For official Belgrade, academic Zajmi specified several options for dealing with the Albanian issue: the first, through “renouncing the continuous territory of the Albanian ethnic majority in Yugoslavia that would lead to unification with Albania after the Second World War”; the second – through “the constitution of the Albanian Republic in the continuous territory of the Albanian ethnic majority, within the Federation of Yugoslavia; the third – through “the status of the republic of Kosovo”.

But, as a counter-response to the demonstrations of ‘81, in ‘89, Serbia’s anti-constitutional amendments followed, “to bind Kosovo (but also Vojvodina) into the links of the structure of Serbia, before the possible dismemberment (demembryony) of Yugoslavia”, noted academic Zajmi. He had formal and substantive remarks regarding the substance of strengthening decision-making in the Assembly of Kosovo. “The consent for the constitutional amendments of the Socialist Republic (March 23, 1989) did not even exist,” he emphasized. This paradox, “could also be confirmed by the minutes of the meeting of the Assembly of Kosovo, when the existence of a quorum for work or for making decisions was not even ascertained,” according to him…!

With the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia, this profound personality in deeds and thoughts insisted that Kosovo and the Albanian people in the territory of the former Yugoslavia be “subjects of deciding on their own historical destiny, in new historical circumstances, according to the principle of national self-determination”. However, the opposite happened. The initiative to collapse Kosovo’s autonomy, namely the suspension of Kosovo’s legal and political subjectivity as a federal unit in the former Yugoslavia, which was strengthened with the issuance of several Serbian laws (1990), according to him, increased “the moderation of the option of Kosovo’s independence compared to the option of territorial unification of Albania, Kosovo and other lands of the Albanian ethnic-territorial majority in the Balkans”.

In this vein, his sharp pen expressed political foresight: “if any major project on long-term stability in the Balkans were to be drafted, it is certain that the problem of the principled solution of the Albanian question, with objective ethnic and demographic criteria, would occupy a central place in it”, he wrote. He was the man who put forward the thesis of the “subjective polycentrism of the Albanian nation” in the 1990s. “The subjective polycentrism of the Albanian nation in the Balkans, at this stage of developments in Europe, is not a factor of national division but on the contrary, in inherited conditions of geopolitical divisions of the nation, it is a factor of the rise of national subjectivity, national integration and processes of national unification”, he judged.

As for the information of the readers, let us just mention in passing how the role and influence of academic Gazmend Zajmi was positioned (with irony!) during the process of constitutional changes in the Serbian press of the time. “It is known that he was very active, as a professional advisor and consultant” even in the last constitutional reviews and sent as an activist to various municipal centers (even on television screens, he was seen in the Aktiv of Gjakova), therefore it is not surprising that the opposition to the constitutional changes was so strong and persistent”, it was said in the Serbian press.

Otherwise, there were: the Constitutional Declaration of Kosovo (July 2, 1990), the Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo (September 7, 1990) and the Resolution on the Independence and State Sovereignty of Kosovo (October 18, 1991), those formal legal-political projections of Kosovo’s independence, which contradicted the amendments to the Constitution of Serbia, of March 23, 1989). Articulated also in the Letter of the Government of the Republic of Kosovo, of December 1991, the reasons for Kosovo’s sovereignty were not convinced even by the Peace Conference and the Baden-Württemberg Commission. They left the issue of Kosovo out of the discussion, left it as a challenge for nationalities and groups and under the tutelage of Serbia.

Meanwhile, academician Zajmi brilliantly stated that “there is no objective legality and no common social-psychological framework for these two separate ethnic-territorial individualities, Serbia and Kosovo, completely different in terms of their ethnic composition, to be or be put under the power of one of their ethnicities, even if the power of one ethnic Serb were not at all distinguished by its current ethnocratic brutality”. Here, when Serbia talked about Kosovo, as its internal issue and they were equal from a constitutional perspective, “how can the political fate of one people be the internal issue of another people”, asked academician Zajmi.

With his intellectual skill, he brought to the attention of the public the assessment that; “The Federation took upon itself not only the continuation of injustice towards the Albanian nation in the Balkans, but it also took upon itself the fundamental nucleus of high instability” and neatly concluded: “the artificiality of a new state creature may also be linked to the injustices in the foundations of that state creature, just as the injustices in its foundations convey to the Federation its artificial character”. These problems surrounding the federation intensified dramatically in part of the Yugoslav space, after Serbia and Montenegro declared the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1992).

Prof. Zajmi’s professional objections are endless, attributed to the Serbian thesis that; – fundamental freedoms and human rights constitute the crucial spectrum of the Kosovo issue. This visionary personality warned that these lead to the “risk of war breaking out”, as will happen (1998/99) three years after his death (1995), because, according to him, the Kosovo issue is expressed by “the ethnic, historical, political and international character of Kosovo, its independence and its position”. As an integral part of the Albanian issue, Prof. Zajmi recommended that the Kosovo issue should be understood through “the relations between the Serbian nation and the Albanian nation in the Balkans, as two of the great nations in Balkan relations, with no less weight than the relations of other peoples in the Balkans, for peace, stability and cooperation in this part of Southeastern Europe”.

He identified “pivotal axes” that outline the individuality and independence of Kosovo, as emblematic values. The first: “the national demographic-territorial reality of the Albanian people of Kosovo”; the second: “the complex historical, geographical, structural-national and political individuality of Kosovo”; the third: the individuality and equality of national collectives for independence” and the fourth: “the political and democratic will of the people of Kosovo, for independence”. Thus, Kosovo is avoiding any kind of connection with the Serbian state. “Academician Gazmend Zajmi is the first intellectual in the ethnic lands to mention the “occupying” notion of the Serbian state towards Kosovo, in his works of a legal-political nature”, claims Prof. Dr. Osman Ismajli, a former student and colleague of Prof. Zajmi.

I recall that the pearls of this rare academic profile, throughout the mission with the main theme of Kosovo’s statehood, radiate his triple contribution, which accompanied the drafting of the source acts of Kosovo’s political self-determination, for sovereignty and independence. Expressed in laconic and exhaustive language, these could perhaps be summarized as follows: The first contribution refers to – his authorship for the drafting of the text which he titled: “Constitutional Declaration for Kosovo, as an independent and equal unit, within the framework of the federation (confederation) of Yugoslavia”, which became synonymous with his name. This act, which he had first promoted on June 14, 1990, at the Assembly of ASHAK, remained confidential for two weeks, until July 2, 1990, when 111 delegates of the Assembly of Kosovo approved it, at the entrance to this closed facility.

This Declaration, among other things, “expresses and proclaims the original constitutional position of the population of Kosovo and of this Assembly, as an act of political self-determination within the framework of Yugoslavia”. The second contribution refers to the protagonism of academic Zajmi, being considered the leader of the group of intellectuals, because under his scientific and pragmatic care, the draft Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo was drafted, which was secretly approved by 112 legal and legitimate delegates of the Assembly of Kosovo, on September 7, 1990 in Kaçanik. With this monumental work, the long-awaited foundation of the state of Kosovo and the Albanian nation in Kosovo was realized. The intellectual halo and the Kosovar society considered it as; a high expertise in state-making that aspired to build the future of society, headed by a consolidated state.

The third and final contribution refers to the question devised by academician Gazmend Zajmi, put on the ballot of the secret all-people referendum, held from 26-30 September 1991, which brought the Resolution on the independence and state sovereignty of Kosovo, on 18 October 1991 with the “yes” of 87.01% of the voters of the Kosovo population. And finally: these three historical documents, as if they sounded like a response of legal, political and democratic hues, of the representatives and Albanian people of Kosovo, to the war visas torn by Milosevic, anticipated on 28 June 1989, at the gathering of Serbs in Gazimestan, where the 600th anniversary of the “Battle of Kosovo” was celebrated. Memorie.al