By Dr. Nikol Loka

Part fourteen

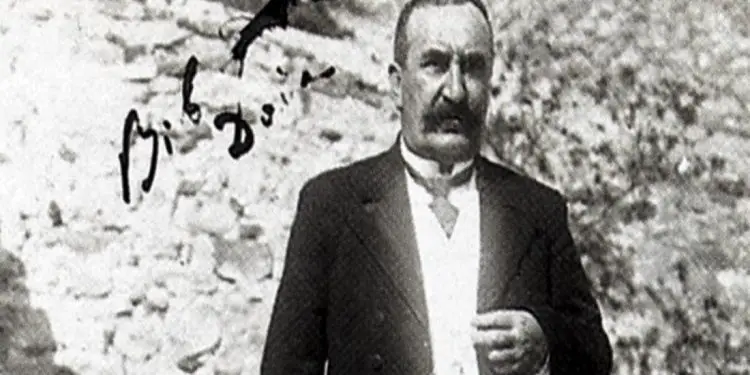

“PRENGA BIBE DODA, THE SHADOWS OF A CITIZENSHIP”

Memorie.al / The newest book “Prengë Bibë Doda, a phenomenon in Albanian political life”, by researcher Nikollë Loka, not only expands the scope of historical studies on Mirdita, the Door of Gjonmarkaj and the figure of the Mirdita Prince, Prengë Bibë Doda, but it is also a contribution to national historiography. The very rich archival material, the literature used or consulted, oral traditions, etc., make this book a real study treasure, giving the science of history a scientific monograph that enriches our knowledge of Mirdita, its captains, tradition, history etc. To study such an important and complex figure, as the figure of Prengë Biba Doda, is a high scientific responsibility that not everyone undertakes. Nikollë Loka, has done a great job of research and treatment by the professional researcher, giving us the portrait of the Prince and the general Mirditor, with the true contours. Dr. Loka has adhered to the end of the space and time, in which the multidimensional events and their protagonists have developed.

THE MONOGRAPH “ABOUT BIBË DODA, A PHENOMENON IN ALBANIAN POLITICAL LIFE”, A VALUABLE SCIENTIFIC STUDY THAT ENRICHS THE FUND OF OUR HISTORICAL STUDIES

(By Mr. Sc. Murat Ajvazi, March 2017, Switzerland)

The Sultan’s pardon

The aim of the attack of the Turkish troops on Mirdita was the destruction of the Doda family, with the aim of removing it from the political scene, since then the Ottomans would find it easy to implement centralization measures there as well. Thus, after occupying Oroshi for the second time, the authorities gave Prenga Biba Doda a two-month deadline to surrender. Since the Captain did not obey, they gave him a second ultimatum, where they informed him that; “If you don’t surrender before November 15, you will be declared an outlaw and your property will be sold.” (257)

Prenga continued to remain a fugitive in Mali e Shejti for several days, and then he went under the protection of his uncles, the Ajazs in Lure. Part of the time, he had also stayed in the big house of the Dodajs. (258)

On March 10, 1878, the Governor of Shkodra, Mustafa Pasha, leaves office and in his place, Porta e Larte, appoints Hysen Pasha, until then, commander of the military troops of Shkodra. (259)

With the new changes, Vienna felt that a solution might be required. On May 9, of that year, the Austro-Hungarian consul, Lippih, protested to Hysen Pasha, about the serious situation created in Mirdita. During the conversation, Valiu had shown refusal and had not created an opportunity for the Consul to ask him about his talks with Prengë Biba Doda. (260)

But the Austro-Hungarian consulate was aware of the indirect talks of the authorities with Biba Doda’s son. Valiu had turned to the Bishop of Lezha, Monsignor Malczinski, who recently returned from Rome, to his post, and to the Prefect of the Franciscan Mission of Epirus, Padre Mariano de Pamanuova, that with their help, they could run the new Captain of Mirdita, to submit and go to Shkodër. On this occasion, he was promised full amnesty, recognition of the rank of “Miri-Miran” and payment of the salary that belongs to this rank.

If Prenga would take this step, then on the basis of this submission, a further agreement could be put on the road, on his recognition as the head of the Mirditas and on the confirmation of the old autonomy of the country. “I,” the consul continues, “I would call it a victory, which should not be underestimated, but how difficult it is for Prenga to trust Valiu, without sufficient security, how difficult it is for him to do so.” I will follow very carefully the further development of the Mirdita case and I will use every appropriate opportunity to support the mutual reconciliation that is being prepared”. (261)

While the honorable situation with Mirdita continued, the High Gate was preparing for the next war with Montenegro. On November 21, 1877, the Montenegrin-Turkish war began again, and on this occasion, Prengë Bibi Doda, wrote to Prince Nicholas that; “The supporters were ready to take up arms.” (262)

The readiness of the Mirdita fighters to take advantage of every opportunity to expel the Turks from the region set Austrian diplomacy in motion, which was interested in the Montenegrins losing the war and the expansion of Slavic influence in the Albanian territories.

The Consul General of Austria, Lippih, who arrived from Vienna with fresh instructions, advised Prenga, with a contingent of Mirditas, to offer Turkey his help against the Montenegrins. (263)

With the intervention of the diplomats of the Great Powers, the High Gate announced the pardon of Prengë Bibë Doda and canceled the establishment of the Ottoman administration in Orosh. The Mirditas returned to their burnt houses, but did not surrender their weapons. (264)

After the official apology, on April 30, Prengë Bibë Doda wrote to Vali, that; “he was grateful for the pardon given to him by the Turkish authorities”. His apology was announced by the Foreign Minister of the Ottoman Empire, in the presence of the French Ambassador in Istanbul. However, the cessation of hostilities between the Mirditas and the Porta did not resolve the resulting conflict. The French consul thought that; “only by recognizing Prengë Bibë Doda, as the legitimate head of the Mirditas, the Porta can remove other temptations and compromises”. (265)

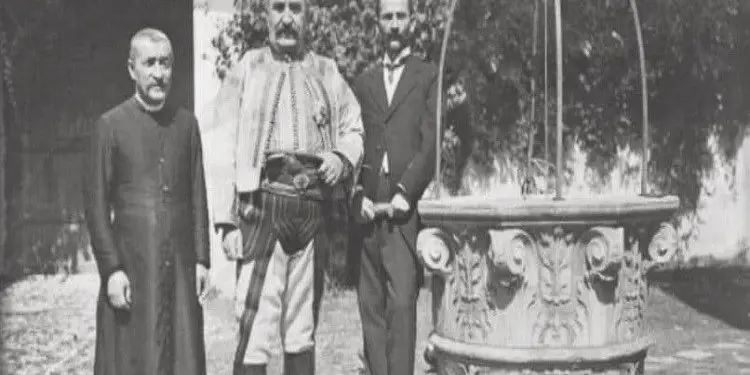

“With other compromises”, the French diplomat meant the destabilizing actions that could happen in the future under the instigation of external factors, mainly Serbian and Montenegrin. Meanwhile, after it was guaranteed that he was under the protection of the Great Powers, Prengë Bibë Doda, fell in Shkodër and was received by Valiu. On May 18, 1878, Prengë Pasha, accompanied by his cousin, Kapidan Gjon Marku, was received by the Governor of Shkodra, Hysen Pasha, with whom he had a short conversation and immediately returned the visit, which took place in a manner visible. (266)

The High Gate truly forgave Prenga, but did not recognize him as the Head of Mirdita, however, now that he was in Shkodra, the Province acted completely under his orders. This attitude of the authorities did not prevent the Captain from maintaining relations with the Mirdita chiefs and performing the functions of their traditional Chief, in accordance with the Mountain Canon. In those conditions, Mirdita continued to be self-governed by its leaders, remaining ungoverned by the authorities. The lack of a ruler who was recognized by the local population made the tribe even more independent from the High Gate. The people of Mirdita were determined not to have any relationship with the government without recognizing Prengë Biba Doda as their leader. So, without Prenga Biba Doda, the influence of the Ottoman state in Mirdita was almost non-existent.

Porta gave no signs that it was moving towards a final reconciliation with Mirdita. On December 10, 1878, while I was there, Jusuf Sokoli was appointed. In connection with this development, the Austro-Hungarian consul in Shkodër informs Vienna: “I have the honor to announce the new receipt of your Excellency’s script, with 29 sequels, and the attached copy of the news of His Excellency Mr. Ambassador, Count Zichy with 9 successors No. 89: “On the sending to Mirdi of the kaymekam Jusuf Sokoli. I take permission to emphasize once again, as a response to Hysen Pasha’s telegraph addressed to the former Vizier Savfet Pasha, that allegedly “the requested measure did not contain any change of the “status quo”, because other times they had been sent to Mirdita, Turkish kaymekama and there, they had exercised that function.

The sending of Jusuf Sokol in itself contained a new thing, and therefore it changed the situation until now, why they had really been appointed kaymekama in Mirdita, but had never exercised their duty there. Until the death of Bibë Dodë Pasha, who was known by the Porta as the head of Mirdita (ie until 1867), no kaymekam had been appointed. After his death, and especially when Prengë Pasha was in Istanbul, they began to appoint him “pro forma”, among whom I have the honor to mention Hajdar Aga, Reshit Beu, Jusuf Efendi and Dervish Beu, but none of them exercised it function in Mirdita, because she never knew them, they were all, as I said, “in partibus infidelium”, whose biggest job was to get the salary; and of course the appointees were friends of the previous governors, who through that title, earned something like a tip for themselves.

How it came about that, after the return of Kapidan Pasha, more work was taken over, is not to be mentioned today. It is not only a political change of the “status quo” in Mirdita, but also a military change, why instead of the battalion that was in Kashnjet at the time of the Congress, he officially announced his dismissal, he always continues to keep it in that place and so, if possible, he has prepared such events, which create the impression of joint responsibility in the mistakes of Hysen Pasha”. (267)

Time proved that; even Jusuf Sokoli could not stay in Mirdita and took the spoils and ran away. Only the gendarmerie major, Dodë Gega, stayed in the country. (268)

Prengë Kola, the son of Kapidan Kola, who the English consul had brought with him from Cetina and who had received orders to go to Istanbul, was seen as a contender for the post of kaymekam. It is very possible that the Consul General of England, giving his hand to the Turkish government, aimed to bring out a competitor for Prengë Biba Doda, so that his Embassy would support him. This mirditas seems to have agreed with him, because as I have been told, he is very ambitious. (269)

The efforts to appoint Prengë Kola did not yield results and Mahmut Aga was appointed instead, but his appointment was frowned upon by most of the Mirditas and there was a risk that it would become the cause of some serious complications in the country. (270)

Regarding this name, the French Consul in Shkodër writes: “As a result of the appointment of a Turkish kajmekam and Kapidan Prengë Kola, as his advisor, a great disaster is reigning in Mirdita”. (271)

In 1879, the High Gate appointed Kapidan Kola, Muhav (Advisor to an Ottoman government). Kapidan Kola was the father of Prenga Kola and the son of Prenga Markola. Kola had no influence in Mirdita and in the first years of the Balkan crisis, he stayed in Montenegro, under the influence of Krajl Nikola. If we trust the security of the consular manager of France Mr. Pons, on the initiative of Mr. Fourniers, through Safvet, regarding the question about the mission of Jusuf Sokol in Mirdita, Hysen Pasha, had to deny it outright, because he still insists that; “The Kajmekams have governed in Mirdi before, and the appointment of the current one does not form a “status quo”.

Hysen Pasha, has given so many proofs of his hypocrisy, that one less, or more, does not lead to punishment. It is to be mourned the fact that as the High Gate, although a staunch opponent of the Turks, in 1876, Kola was put at the head of the movement in Mirdita. During the years of the movement, he left his son Prenga in Montenegro, who stayed there as Nicholas’s guardian until 1879. After the suppression of the uprising by the Turks, Kola stayed on the mountain, like many other Mirditas and together with them and under his leadership, Jusuf Sokoli was attacked in November 1878. “The captain of Mirdita, Kola”, – writes the Consul of France in Shkodër, has always been distinguished for his enmity against the Turks and until now, he has not agreed to submit to the Ottoman government. Finally, Hysen Pasha has set a price for his head. (272)

Valiu had called Dodë Gega and the leaders of the Mirditas, who were mercenaries of Turkey, and had made it clear to them that he wanted “to bring them 150 Mirditas, of 30 men for each flag, who should be brought alive or dead, Captain Kola”. (273)

The British consul, after obtaining permission from Ali Hajdar Pasha, summoned Kola to Shkodër. At the end of September of that year, Kola went to Shkodër in the morning to meet with the Consul. Here he found out that his son had been removed from Montenegro and had been ordered to go to Istanbul, as the Sultan was looking for him. Seeing that he was betrayed by the English Consul, on the night of October 5, without notifying anyone, Kola fled to Mirdita, to organize the resistance. (274)

The appointment of Kola as Muhavin of the kajmekam, Mehmet Aga, made quite an impression on the foreign consulates, accredited in Shkodër, on the residents of that city, as well as in Mirdita. The people of Mirdita thought that Kola was “sold”, while the foreign consuls, especially those of France and Austria, were indignant with the Governor, because he was not implementing the Berlin protocol for Mirdita. The appointment of Mehmet Aga as Kajmekam and Kolë Prenga, as his deputy, was seen as an attempt to subdue Mirdita and split the Albanian League. (275)

Regarding the situation created in the country, the magazine “La Guerre d’Orient” writes: “A telegram arrived in Istanbul, informing us that on May 7, the uprising was completely extinguished here. Is it true? What was the outcome of the dispute: This was rumored because the Mirditas did not follow and gave Turkis the usual help in the war against Montenegro. The opposition was provoked by the Sultan, who wanted to put me at the feet of the hereditary Chairman of the tribe of Gjomarkaj, a kajmekam”. (276)

From “friendship” to enmity with Montenegro

The Montenegrins did not like the Mirditas and saw them as an obstacle to the realization of their projects, to extend towards the Albanian lands, but the Mirditas did not like the Montenegrins either. The history of relations between them is full of wars, where the ancestors of Prengë Bibë Doda, in alliance with the Bushatllinjes, have attacked and subjugated this country several times, at the expense of the Sultan. In the subjugation of Montenegro, Kapidan Prengë Lleshi participated twice, in 1790 and 1795, and after him, Bibë Doda in 1852.

This is what is said in the chronicle of Mahmud Pasha’s death in 1796: “Fight, my dear ones! Take revenge for the Pasha who was left alone, because you were not there… O my brave mirditors, take revenge for your Pasha, because if you had been on the battlefield, he would not have been left alone… Before the mirditors of brave me! Make these traitors, who shed tears of blood, to take revenge for Pasha…”! (277)

The battles of the Albanians with the Montenegrins had also taken place in the pages of the European press. In the magazine “Leka”, an article from the magazine “La Guerre d’Orient” has been reprinted, where it is written: “In June 1876, the Mirditas opposed the mobilization to fight against Montenegro, as long as they did not have the son in charge of Biba Doda. “Mirdita, here’s Grisha to participate.” (278)

They declared that they were ready to send their contingent, as long as they returned the young man Prengë Doda. (279)

So the Mirditas were ready to fight for the Sultan, on the condition that their traditional self-government was respected. On the other hand, Austria made many efforts to remove Prenga from the influence of Montenegro. (280)

However, in April 1776, Prince Nicholas gave Prenga’s envoys 6,000 francs and ordered them to be quiet. (281)

In the absence of aid from any other country, the Mirditas were forced to reach out to the Montenegrins, being forced to knock on every door. The Montenegrins were helping the Mirditas in the war, because in the long run, they thought that war would end with the desolation of Mirdita, so they would benefit from the reduction of its fighting power.

Prenga knew these intentions, so when the Montenegrin-Turkish war began, he kept Mirdita out of the conflict, the Mirditas did not move and left the Turkish army alone, in the rear. After the decision of the Great Powers to give the Albanian territories to Montenegro, the Mirditas, regardless of the reservations they had about the attitude that had been taken towards their uprising, joined the other Albanian forces. The formation of a certain national consciousness will have been a factor for this attitude.

The Austrian consul, Lippih, thought differently, according to which; “one of the reasons that pushed Prengë Bibë Doda to accept the rapprochement with the Albanian League, was the concern he was feeling, because the High Gate in those days was insisting on replacing the authority of the Mirdita Kapidan, with a governmental mydir”. (282)

This fact would not serve to bring the Head of Mirdita closer to the Ottoman authorities, on the contrary, it would further distance him. The developments of the events themselves had laid the need for the unification of the Albanian factor and Mirdita could not stand aside in this process. When the chiefs of Hoti, Gruda and Kelmendi, as well as many Catholics of Shkodra, went and asked him to be put in charge of them, the Captain, before giving the word, wanted to see what the benefits would be his and himself from this commitment. (283)

Of course, Prenga, as a politician, wanted to derive benefits from this new movement of his, but the readiness shown for war against the Montenegrins proves that there was never a “honeymoon” between Mirdita and Montenegro and before the benefits from the cooperation with the Montenegrins, for him it was better a smaller benefit, but which included Mirdita, in the Albanian movement.

In the conditions of the Head’s readiness to fight against the Montenegrins, the dedication issued by the Sub-committee of Shkodra was strongly felt in Mirdita. The Assembly of Shpal, on April 27, 1880, decided that Mirdita would contribute a contingent of 2,500 men under arms. The first contingent of 800 fighters left the next day, April 28, and belonged to the bajraks of Orosh, Spač and Kuzhnen. On May 4, the second contingent also left. The Mirdites gathered in Kallmet for a short break and, dressed in national costume, demonstratively entered Shkodër, as if there were no invaders in that city.

After resting for two days in Shkodër, on May 6, they left Kastrati, crossed by boat from Hani i Hoti pier and from there, entered Tuz. With the arrival of the Mirditas in that city, the Albanian insurgent forces numbered 12 thousand people and were already ready to forcefully oppose the intention of the representatives of the Powers of the Congress of Berlin. (284) Memorie.al

- Kolona Çekald, Consul of France in Shkodër-Dukës Dekaz, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Paris, Shkodër, October 26, 1877, Albania in the years of the Albanian League of Prizren, volume I

- Fatos Mehdi Daci, Big men of Dodaj, Tirana 2011, p.54

- AIH, Vj.30-68 (HHStA, PA, A, No.19), Report of the Austro-Hungarian Consul in Shkodër, Lippich to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Count Andrassy in Vienna regarding the situation on the borders of the Ottoman Empire with Mali e Zi, Shkodër on March 11, 1878, see p, see Albanian League of Prizren in Austro-Hungarian documents, Volume I, “Albanica” publications, Tirana-Prishtina 2008, p..33.

- AIH, Vj.30-75 (HHSTA, PA,A, No.43) Report of Consul Lippih from Shkodra to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Austria-Hungary, about the situation in Mirdita, Shkodër, on May 11, 1878, see Albanian League of Prizren in Austro-Hungarian documents, Volume I, “Albanica” publications, Tirana-Prishtina 2008, p.78

- HHStA-PA-Vj.30-75, Report of the Austro-Hungarian Consul in Shkodër Lippih to the Minister of Foreign Affairs Ahrental in Vienna, Shkodër on May 11, 1878, see the Albanian League of Prizren in the Austro-Hungarian documents, Volume I, publications “Albanica”, Tirana-Pristina 2008, p.78-79

- Column Çekald, Consul of France in Shkodër-Dukes Dekaz, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Paris, Shkodër, November 27, 1877, Ligor Mile, Albanian League of Prizren in French documents, vol. I-II, Tirana: 1978-1979

- Column Çekald, Consul of France in Shkodër-Dukes Dekaz, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Paris, Shkodër, December 20, 1877, Ligor Mile, Albanian League of Prizren in French documents, vol. I-II, Tirana: 1978-1979

- Column Çekald, Consul of France in Shkodër, Vedington, Minister of Foreign Affairs of France, Shkodër 4 May 1878, Albania in the years of the Albanian League of Prizren, volume I

- Albania in the years of the Albanian League of Prizren, volume I

- AIH, Vj. 30-3-367 (HHStA, PA, A, Fk. 344-345, Report of the Austro-Hungarian consul in Shkodër Lippih to the Ambassador of Austria-Hungary in Istanbul, Count Zicchy about the situation in the Albanian provinces, Shkodër 24 May 1878, p .88-89

- Lippih, the Austro-Hungarian consul in Shkoder addressed to the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Vienna, Shkoder, 10 – XII – 1878, taken from “Leka”, cultural monthly magazine, No. VII-XII, year 1939, special issue Prizren League , p.192-193

- Instructions of Minister Andrassy sent to the Austro-Hungarian consul in Shkodër Lippih, Tiszabod 24-XII-1878, taken from “Leka”, cultural monthly magazine, No. VII-XII, year 1939, special number League of Prizren, 202

- Le Re, Consul of France in Shkodër, Furnia, Ambassador of France in Istanbul. Shkodër on October 5, 1879, AIH, French Documents, Vol.21, fi.353r-357v.

- Le Re, Consul of France in Shkodër, Vedington, Foreign Minister of France, October 25, 1879, AIH, French Documents, Vol.21, fi.353r-357v.

- Le Re, Consul of France in Shkodër, to Weddington, Foreign Minister of France, November 14, 1879, AIH, French Documents, Vol.21,fi.353r-357v

- Lë Re, Consul of France in Shkodër, Vedington Foreign Minister of France, November 14, 1879, HHStA-Pa-Vj-1.11, No.1, Report of the Consul of Austria-Hungary Lippih sent to Baron Henrich Von Haymerle, Shkodër on December 14 1880

- Report of Lë Re, Consul of France in Shkodër sent to Furnies, Ambassador of France in Istanbul, Shkodër on April 12, 1879, AIH, French documents, Vol.21, p.353r-357v. 274. Report of Le Re, Consul of France in Shkodër sent to Furnies, Ambassador of France in Istanbul, Shkodër on April 12, 1879, AIH, French Documents, Vol.21, p.353r-357v.

- HHStA-Pa-Vj-1.11, No.1, Report of the Austro-Hungarian Consul Lippih sent to Baron Henrich Von Haymerle, Shkodër on December 14, 1880

- La Guerre d’Orient in Europe e in Asia, No. 4 p. 35, taken from “Leka”, monthly cultural magazine, No.VII-XII, year 1939, special issue Lidhja e Prizren, press “Zonja e Papërlyeme”, p.202 277. Haycynthe Hecquard, History and description of Upper Albania , p.443

- La Guerre d’Orient in Europe e in Asia, No. 4 p. 35, taken from “Leka”, cultural monthly magazine, No.VII-XII, year 1939, special issue Lidhja e Prizren, print, “Zonja e Papërlyeme”, p. 202

- Column Çekald, Consul of France in Shkodër-Dukës Dekaz, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Paris, Shkodër, July 14, 1876, Albania in the years of the Albanian League of Prizren, volume I

- Column Çekald, Consul of France in Shkodër-Dukës Dekaz, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Paris, Shkodër March 8, 1877, Albania in the years of the Albanian League of Prizren, volume I

- Kolona Çekald, Consul of France in Shkodër-Dukes Dekaz, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Paris, Shkodër, April 5, 1877, Ligor Mile, Albanian League of Prizren in French documents, vol. I-II, Tirana: 1978-1979

- Report of Lippih, Austro-Hungarian Consul in Shkodër, No. 65 addressed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Vienna, Shkodër, July 18, 1878, Albania in the years of the Albanian League of Prizren, volume I

- AMAE CPC Consulate of France in Shkodër, volume 22, p.81r-84r

- Eqrem Bej Vlora, Kujtime,…p.p.163