Part one

Memorie.al / Hazis Ndreu, born in the city of Peshkopi, is one of the survivors of the Tepelenë internment camp. He spent 43 years in internment, starting at the age of 14 in Kuçovë, after his father fled to Yugoslavia, and continuing in Berat, Tepelenë, Bënçë, Myzeqe, Llakatund, Lubonjë, and Vlorë. His internment ended in 1990, but he endured the hardest years in the Tepelenë internment camp, where he recounts the tortures, persecutions, and sufferings of the internees through forced labor, punishments, penalties, filth, lack of food, clothing, medicine, and diseases like dysentery, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and bronchopneumonia. Due to the numerous illnesses and deaths in the camp, the command appointed Hazis as a medic and later as a camp nurse.

Mr. Hazis, what happened to you after your father fled?

Two of my uncles were killed. They were executed by the [Communist] Party, while my mother, sister, and I were interned in Kuçovë.

How old were you?

14 years old. Together with my mother, we were isolated in a cell in Peshkopi; then we were interned in Kuçovë. They housed us in some barracks, which the Italians had built for oil well exploitation. The police would call roll twice a day. We children did not go to work; the others worked in agriculture. They sowed wheat, and we ate cornbread. That’s how we lived, with only 400 grams of cornbread. We had nothing. When we were interned, we left with only the clothes on our backs. We only took a blanket. If you had any money, you could buy something, of course, with the command’s permission.

How long did you stay in Kuçovë?

We stayed for 3 months, and then we were housed in the castle of Berat, in rooms without doors and windows, abandoned from the war. Some were placed with families. In one room, two or three families together. If you got sick, you had to get a document from the Internal Affairs Branch to go to the hospital. The heads of families were obligated to report to the Internal Affairs Branch once a week.

Every Saturday, the police would call roll. In the spring of 1949, they transferred us to Tepelenë. Let me tell you about an accident. After we left Berat, a car went off the road and rolled down a cliff. The convoy stopped. We got down helping. What did we see? Women, men, children, elderly, were scattered in the bushes and brush, covered in dirt. In this accident, the Petrela couple died.

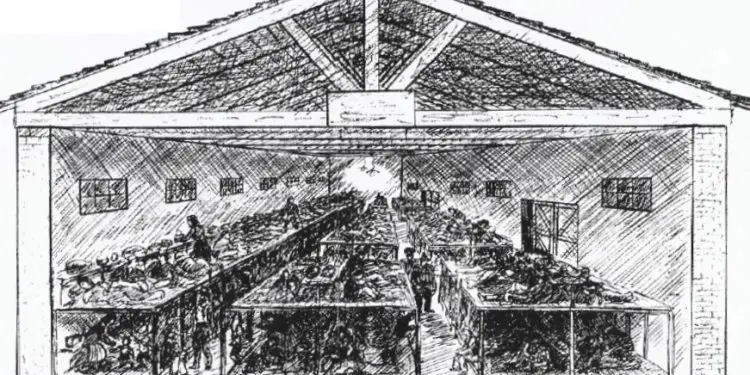

One of the children, 1 year old, was left in the bushes. I took him, and this is Seit Petrela, who is still alive today. When we went to Tepelenë, they housed us in the Italian barracks. We were so many that they couldn’t fit all of us. Some slept outside. There was no electric light. One lantern stood by the barrack door. This lantern was not to be turned off or taken with us. Control was so strict that roll was called three times a day. We got our bread in Tepelenë, cornbread. Nothing else.

There were no shops. Children from 14 years old and up were mobilized to work on the Veliqot-Memaliaj road. I don’t know where to begin. They would take the bread and boil it. Add water and add some greens, that are how we supplemented our food to eat. After 2-3 weeks, another convoy arrived. In Mirditë, an assassination had occurred. Bardhok Biba had been killed, and whatever the State Security had found, they brought the internees to Tepelenë. The camp’s number reached 3200 people.

How did you live, what did you do?

Only with 400 grams of bread. It wasn’t long before typhoid and dysentery broke out simultaneously. Death began in series. There was no ambulance and no medicine. An isolated place, forest, epidemic. A squad was created just to dig graves. It would go to dig 2-3 graves and then would be informed to dig another and another…! There were cases of 5-6 graves a day.

How high did the number of dead reach?

Who could think to count and register them? We were all hopeless. There wasn’t even talk of surviving or living beyond that hell. One day, Dr. Hazika came from the city. As soon as he saw the situation, he put his hands on his head and said: – “What can I do here? Cholera has broken out here!” He went to the command and told them: – “Send them to Gjirokastër, they can’t be treated here. Neither typhoid nor dysentery can be treated in the camp.” After the alarm raised by Dr. Hazika, some were taken to Gjirokastër, but in vain. Some died on the way, and some in the hospital.

Let me tell you an episode. A woman from Mirdita had 2 small twin children. She was tending to one, who was very sick. While she was tending to him, when she turned her head, she saw the other had died. She began to wail loudly, as Mirditores know how to wail. A trembling wail that would break your spirit. Then she stopped crying. When suddenly, what do I see! The other child was also passing away. She fell silent and began tearing her hair out. People gathered around her. They tried to calm her down. From crying, she started laughing…! She went mad!

Where did you live?

In the barracks. One barrack held 400 to 500 people, as needed. As soon as we were settled in the barracks, a new organization began. Each barrack had 3 companies. Each company had a person in charge, and each barrack had another person in charge, from among the internees. Wake-up and roll call was at 5 in the morning. Winter – summer.

Who conducted the roll call?

Roll call was conducted by the command, uniformed police, armed. We were obligated to come out of the door to be counted one by one. The police would call the name, and we would come out in order. If you were late, they would take you to the cell. After we came out, we went back inside. The workers would take their soup and line up before the command.

Accompanied by police, they would climb Mount Turhan to cut wood. One part would cut wood. The other part would load it on their backs. Whoever had a rope was fortunate. Some loaded it on their backs with wire. They brought it down from the mountain to a field. Each person had to produce half a cubic meter.

Did you work?

I worked what could I do, even though I was 14 years old! In the evening, we loaded wood to take to the city, to the Internal Affairs branch. It was an hour’s walk. The load was checked by the police. He determined how much you would load. Along the way, there would be a scream if someone fell. The police would come immediately and kick them. At that time, the police’s shoes had iron tips.

If someone was sick, those who were healthier would go behind and lighten their load. We young people were punished more because we couldn’t carry the wood. During work time, we neither ate nor drank. Barefoot, undressed. Late in the evening, we returned to the camp.

What about your mother, what did she do?

My mother, like many other mothers, died of tuberculosis. Today, she doesn’t even have a grave.

Were there no doctors and medicine?

There were doctors, but there was no medicine. A person sick with tuberculosis needs food and hygiene. We had neither one nor the other. We didn’t even have clothes to cover ourselves with. We had neither clothes to neither wear nor bread to eat. We took my mother to Gjirokastër, and she died there.

Who took the body?

If you died in Gjirokastër, the body was taken by the Gjirokastër command. When they died in the camp, we would take them to barrack no. 6, which was empty; we would mourn that night and then bury them. The graves of the Tepelenë Camp have been opened and closed three times. Initially, the cemetery was near the camp, then by the bridge, and finally near the river. The tractors that opened new land destroyed all the graves.

We had no right to ask for information or move around to see the graves of our people, because we were surrounded by barbed wire. Since there were many sick and many deaths, the command appointed one medic for each barrack. One of these medics was me. By watching, studying, within a very short time, with the help of the camp doctor, I became a nurse. Memorie.al