By Bajrush Xhemaili

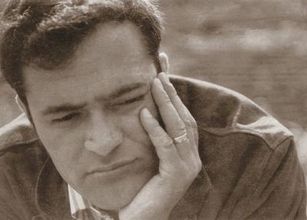

Memorie.al / I had heard and read so much about the esteemed professor Ukshin Hoti, but I had never had the chance to meet him. I met him for the first time in the “Dubrava” prison in Burimi (Istog). Initially, we saw each other from afar from the pavilion promenades. I was in Pavilion C-1 and he was in the reception pavilion. Even from this distance, we had no difficulty (since we were here) in distinguishing him: seven feet tall, broad-shouldered, slightly stooped and almost always with a haze of smoke around him, from his heavy smoking. Fate decreed that when they brought him to our pavilion, we would find ourselves in the same room, until a bed became available in the overcrowded rooms.

This intellectual with a wide range of knowledge in different fields and a rare depth of judgment, at first, left the impression of a gloomy and withdrawn man and not communicative. But, in fact, in the long discussions and polemics that we had with him in prison, he was very active, strict and uncompromising.

Another characteristic that was easily distinguished was that he was very worried about his family situation, which was burdened with numerous problems, in particular, he was saddened by the suffering of his three children, due to the separation from the two wives he had had. The extent of this pain was magnified even more, on the occasion of the visit that his son, Andin, paid him.

When he returned to the ward, after each visit, he commented on Andin’s mental and physical condition. He seemed to be in a bad mood, that he was slowly growing and that every day he was becoming more and more stubborn. He was extremely worried about him. But above all, his rebellious spirit attracted attention. His character did not allow an indifferent contemplation of all the injustices that were done to political prisoners, as well as ordinary ones, and he did not hesitate to go on a hunger strike for them.

Things got to the point that the prison superiors could no longer tolerate this incorrigible rebel. That is why they will transfer him to the Niš prison. There, he will then continue to run the prison in his own way, which was not ordinary from the point of view of those who make evil plans.

The letters he wrote to his sister Myrveta (now published and known to the general public), and his dignified attitude towards them, stirred the spirits of the prison superiors. And, undoubtedly, also the prison managers at the highest levels of the Serbian state. For this reason, they will transfer him to the Mitrovica Srem prison.

50 days of torture and solitude…!

In the prison of Mitrovica in Srem, one of the cruelest directors you can find in prisons, wherever they are, awaited him. For the tortures he had inflicted on Croatian political prisoners, it was said that he was also accused by the International Tribunal in The Hague. He organized the same bestial tortures for us Albanians to whom we had been transferred since April 30, 1998, and for those who had come later. Especially the group headed by Nait Hasani, and professor Ukshini will also be subjected to these tortures, for about fifty days in a row, for which they will keep him in solitary confinement.

Later, when we would meet in a common room, he would tell us about the cruelty that was done to him: “From the strong and uncontrolled falls, at first it seemed to me that one arm went then the other arm, later my back, my legs… I simply had the feeling, and I was convinced, that they had decided to kill me, by torturing me”.

And after all this, he would no longer be brought to a common room with us Albanian political prisoners, but would be placed in a place with other prisoners, for various ordinary crimes, with different nationalities. In fact, even though we were in complete isolation, he would have an easier time in society with us, than with those prisoners dominated by Serbian criminals, but who had a treatment where they were freer.

The news about the NATO attacks was given to us by Professor Ukshin

We were together (a total of 44 Albanian political prisoners), even two days after the start of the NATO bombing of Serbian targets, when Professor Ukshin was brought to our room, on which occasion he gave us the joyful news of that attack, so awaited by the Albanians. They will keep us there until April 26, 1999, when they will transfer us to the Niš prison, just as infamous as the one in Mitrovica and Srem. In Niš, the “explosion” will await us, composed of almost the entire potential of the guards of that prison.

The “explosion” is that method of torture, where the guards are lined up in two rows and the prisoner must pass through these two rows. The police shoot wherever, however, and as much as they want, until they are satisfied. It was a truly brutal beating, where, in addition to the usual kicks and rubber bats, simple sticks, baseball bats, and iron bars were also used during the beating. A lot of blood flowed and bones were broken. Woe to the one who fell! A prisoner had to risk himself even more to get him out of such a situation, because the falls did not stop. Many prisoners fainted.

Professor Ukshin’s turn also came. In that chaos, at first those who were carrying as much as they could did not notice him. But when one of them realized that it was the professor, he shouted happily: “Look, look! The professor is back!” And he fell on him even harder than before. When the professor heard that ironic remark, as he was hunched in a defensive position, he straightened up and walked forward proudly and stoically, facing all those blows! That night they would beat us several times in a row and divide us into two large rooms. The professor was placed in the other room.

Then they would torture us several times over the next two days and two nights, until the morning of April 29, when they would order us to get ready for a new transfer. The prisoner never knows when and where he will be transferred. He is constantly haunted by curiosity accompanied by fear that he will have it worse than before. This enigma, what would happen to us in those extremely dramatic circumstances, when Serbia was making its last convulsions, had a very heavy weight on our heads. Even more so, the fact that it had only been three nights since they had brought us to Niš. Where are they taking us?!

Just like in Mitrovica Srem, here too, they tied our hands behind our backs, each one separately, and then they tied us all together with a long chain, which they also reinforced with bus seats. The transfer was not only for those of us who had come from Mitrovica Srem, but for all those political prisoners who had been in the infamous Niš prison. Three buses were filled with prisoners.

Professor Ukshin was one chair in front of me, but we did not manage to exchange a single word on the way, because not only were we not allowed to speak, but we also had to keep our heads so low that we could not see anything, otherwise cruel beatings would follow. Later that day, the riddle was solved: we arrived at the “Dubrava” prison, exactly one day before the one-year anniversary of our removal from this prison.

We all knew: they had brought us there for our own harm.

The return to Dubrava surprised everyone. We all gave some possible version of why we had been returned there. We all knew one thing: we had been brought there for our own harm. A year ago, from here they had distributed us to various prisons throughout Serbia, with the excuse that there was no safety for us in Dubrava, and now they returned and gathered us there, in the greatest possible insecurity, at a time when the KLA was much stronger than a year ago, NATO was attacking incessantly from the air and, at that time, when the Serbian army was committing the greatest crimes against the Albanian population.

In fact, we knew that after our transfer from Dubrava, instead of prisoners they had brought Serbian paramilitaries, specifically Arkan’s “Tigers”. Whereas, before we returned to, they had removed them. And in this regard, the Serbian bloodthirsty had made their calculations meticulously. Seeing that the Serbian military base, the strongest in the Dukagjini Plain, centered in the Dubrava prison directorate, had also come to be bombed, they had brought us so that, in the event of a bombardment, the paramilitaries would not suffer, but the prisoners. We felt this danger, but we had nothing to do, except wait for everything to happen to us.

In these circumstances, we were undoubtedly tense even though we were in Kosovo. Professor Ukshini had one more reason, to feel bad spiritually, because he had one more enigma: how would he manage to return to his family after his release, or to a safe place, or simply where would he be able to continue his life after prison?

He, like the rest of us, had no way of knowing anything about his family and relatives. Even from the little information I managed to get from an ordinary prisoner who worked in the kitchen, we were unable to form even a superficial picture of the situation.

From those small letters, even more dangerous to get to me, we could understand that a fierce war was being waged, from the air and from the ground and that many Albanians had been displaced and many had been killed and massacred. I told the professor and those I trusted, but this news worried and made the professor even more nervous.

“I have definitely decided on a job: I will go straight to my Kruša, and that’s it! From the day we returned, he had only 18 days left until his release and every day that approached he was more worried. How, and where to shock him?! Finally he told us: “I have definitely decided on a job: I will go straight to my Kruša, and that’s it”!

The moment of his release came suddenly. The exact time is not known in prison, because it is not allowed to keep a watch, but it must have been between 10 and 11 o’clock, on Sunday morning (!!!), May 16, 1999, that is, one day before the deadline. The fact that he was released on Sunday was surprising.

By no means is it allowed, nor has it ever happened, for anyone to be released on Sundays. If someone’s release date falls on a Sunday, then that prisoner is released for a day before. Something like this happened to me when I was first released from Pozharavac prison, where instead of being released on Sunday, October 14, 1990, I was released on Saturday, October 13.

Someone entered our room and announced that my uncle Uka was going home and that the supervisor (“nadzorniku”) of our ward, Branku, had come with the supervisor of Ward C-1 to take him out of prison. This meant a high-level and unusual escort. In fact, judging by the words of a guard, who was almost the only one who still behaved correctly with some of us who had been in Dubrava for years, a special meeting was held regarding the date and manner of the professor’s release and there was a long debate about what to do with him. Otherwise, there is no way to explain what he said, when 3-4 days before his day was due of leaving prison, he says: “Well, professor, we have decided to release you, let him go wherever he wants.”

“I just want to say goodbye to you with one word: Goodbye!”

As soon as I received the news that he was being released from prison, I quickly decided to go and say goodbye to him, because when the guards arrive to take the prisoner, they don’t allow you to say goodbye to him as you wish. I also knew that during the goodbye there would be a crowd. We had a wall between the rooms. I also invited Nait Hasan and we went into his room. He had been in the room walking and listening to the comments of his “cellmates”.

As soon as I entered the room, more to give him courage, in the room, more to tell him that; it seems it’s a good sign that they came on Sunday to release you, since this must be the insistence of the International Red Cross and, for sure, your sister Myrvetja also came with them. In fact, I told him something that we wanted to do, and that we had said before.

In any case, this had a positive effect on his mood in those moments of anxiety, for all of us. And we immediately said goodbye. As soon as someone wanted to say goodbye to him, he said: “No, I don’t want to say goodbye to anyone anymore, because I don’t want to take this as a separation, since soon, you will all come, so I want to greet you only with a goodbye”.

This was understood as his attempt to give us courage. We then left the room and until departure he was alone with the “cellmates” of his room. After a few minutes, the respected professor Ukshin Hoti, accompanied by two supervisors, would head towards the prison exit doors. And we never saw him again.

In fact, ordinary prisoners who worked outside would tell us that they had seen the professor, even when he had gone outside the prison walls. Nothing more. After a few days, word spread that the International Red Cross had supposedly tracked him all the way to Italy, and we were all overjoyed that he had finally escaped from the clutches of the criminal regime, the man that Kosovo needed so much.

In fact, we believed this untruth so much that when NATO bombed the prison on May 19, we wondered how the professor had not managed to inform certain international circles that we, the Albanian prisoners, were now in prison, and not the Serbian paramilitaries. We could not have known that once he had gone beyond the prison walls, the professor would lose all trace and no one would know anything about him, so much as to assume that he was alive.

And, really, where could Ukshin Hoti be?

When we were transferred to Lipjan prison (after the Dubrava massacre), an ordinary Albanian prisoner, who was cleaning the corridor and toilets of our pavilion, one day, around June 5, 1999, comes and tells me in secret, from the others: “I heard two guards saying to each other: Oh, the army killed him, he just left 300 meters from the prison”! Then, he adds that the guards did not notice him, where he had eavesdropped. Therefore, it cannot be taken as a provocation against him.

Videotape – similarities and conjectures

Exactly about 300 meters from the prison, around September 1999, a corpse was found. This could also be a coincidence. But, Ukshin’s brother and son-in-law had recorded (filmed) this corpse with a camera. They came to my house, so that while watching the videotape, I could tell them something that I didn’t remember any clothes that the professor was wearing. And, surprisingly, a lot of it matched the clothes that Ukshin Hoti had in prison. Again, it could be a coincidence, but the shoes that I saw on the videotape were similar, if not identical, to Ukshin Hoti’s.

The jeans could also have been the same. They reminded me of a case I knew very well, when a prisoner had given a pair to the professor a few days before he was released from prison. The body I saw on the videotape had a characteristic sweater, just like the professor had and wore.

The only garment that I don’t remember resembling his clothes was a leather jacket. The length of the body was also similar, if not the same, as the professor’s. Ukshin Hoti’s brother, Afrimi, told me that he was also concerned about one issue regarding the body: the body of his other brother Ragip, who had already been found earlier, had his head cut off.

This coincidence of the body also without a head, found and filmed 300 meters from the prison, worried him immensely. Could this be a special signal!!! With all these assumptions, conjectures and coincidences, which close the paths to hope, there are also voices in our information media, which give us encouragement that one day the professor will return to Kosovo, which he loved so much and did so much for. I hope that these, which are said and written in various information media, in favor of his return, become reality as soon as possible. Kosovo needs Ukshin Hoti. Undoubtedly, it needs him a lot. / Memorie.al