From Nafi Çegrani

Part One

Memory and Personal Mission

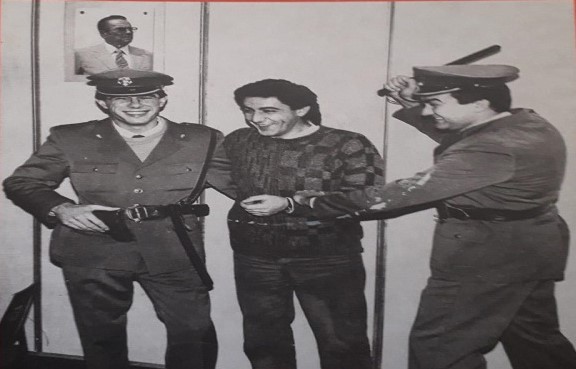

Memorie.al / From my youth, when I served as an operative official in the Yugoslav SDB (State Security Service, or UDB), in 1972, I felt a peculiar sense of responsibility. It wasn’t just the job that obligated me to collect and analyze secret information; it was the feeling that every document, every hidden report, constituted an important part of my people’s history. Every file marked with “Top Secret” was like a window into the past that few dared to open. At the time, I didn’t fully grasp its moral significance. But as months and years passed, as I read the reports on the political activities, persecutions, and violations of the rights of Albanians, I began to understand that history is made up not only of what we have experienced ourselves but also of what must remain alive for future generations.

History is a bridge connecting the past and the future, and I, although an ordinary operative official, felt part of it. In the dusty archives, among the carefully numbered files, I found information about the fate of the Cham people, who lived under silence and occupation, but also about Kosovo, which was experiencing a strict Titoist regime. Every document was a secret history, a testimony that could not be allowed to fade into the darkness of bureaucracy. As I analyzed them, my mind struggled to connect the dots: a report on the confiscation of property, another on minority rights violations, another on fabricated arrests-all these together formed a painful, yet compelling, picture requiring action.

For me, the collection of this information was not merely an operative job; it was a moral and historical duty. Every fact I discovered, every file I flipped through, imposed a responsibility on me: to write, to document, to not allow the truth to be hidden. It was a kind of silent vow-a vow to history and to my nation.

Today, as I write these lines, I feel that strong responsibility again. This narrative is not simply a personal memory; it is an effort to bring the hidden to light and to restore to the collective consciousness what was once forbidden to mention. Every file, every note, and every report that I held in my hand now gains meaning in this narrative-a call to bear witness, to remember, and to preserve the silent truths for future generations.

As I begin this writing journey, I feel a strong connection with every Albanian who has fought for their rights, with every people who have carried the aspirations for freedom, justice, and dignity in their soul and mind. This is my introduction, but also my personal mission-to write what has been hidden under the dust of the archives, to give history and the nation a sincere mirror of the past, the truth, and hope.

The Archives of the Yugoslav Intelligence Service

The archives of the Yugoslav intelligence Service were more than a treasure trove of information; they were windows into the secret, from which one could view the hidden world of power and the people struggling to survive. Every file was coded, stamped with signs that signaled its danger and importance: “Top Secret,” “Internal Use,” or “Publication Not Allowed.” In the early years of my service, I felt like I was just a silent custodian of documents, but I quickly realized that every note, every report, carried historical weight.

Among the numerous files, I encountered reports describing the situation in Chameria. These were operative notes on the expropriation of property, arrests, and the violence exerted by the Greek administration against the Albanian Chams. A 1944 report described the violent exodus of families, the burning of homes, and the confiscation of land. Another 1950 report described the remaining efforts to integrate economically and socially under conditions of occupation. Every sentence written there seemed dry, bureaucratic, but for me, it was a silent light of truth-a testimony of a pain that could not be extinguished.

Similarly, the archives contained reports on Kosovo, where the Titoist regime exerted strict control over the political and cultural life of the Albanians. A 1971 file noted the surveillance of intellectuals who expressed opinions about Albanian rights and at least three cases of political arrests. Another report spoke of the infiltration of service agents into Albanian educational and cultural organizations, overseeing any activity suspected of being “against the state order.”

Every document, every note I analyzed, made me understand that history is not just what is written in books, but also what is kept silent within the archives. For me, these documents were not merely operative reports; they were a mirror of a painful reality, but also a call to action. My mind connected the events in Chameria with the fate of Kosovo: both were parts of a greater history, of a fragmented, stolen, and often forgotten Albanian nation.

And as I glanced through report after report, a vision arose in me-that it was the duty not only of mine but of every conscious Albanian, to preserve this history, to document the truths, and to try to influence the collective consciousness. This feeling also formed my determination to use the information in the service of the public good and national history.

Thus, the secret archives became more than a treasure trove of information; they became a way to understand the depth of pain, the absent justice, and the immense duty of the individual who confronts the secrecy of the past. They taught me that the smallest document can serve as a guiding light to understand the fate of a people and that every secret file contained a part of the nation’s soul that needed to be preserved.

Chameria: The Silent Testimony of Exile

Chameria, the silent land under occupation, always remained on my mind as I flipped through the secret archives. The documents preserved by the Yugoslav services about Chameria were not simply operative reports; they were testimonies of a silent pain, of a people denied the right to exist in their own land.

A 1944 report described in detail the violent exodus of Cham families from their villages: burnt houses, confiscated lands, and a systematic attempt to extinguish the identity of a people. Another 1951 report described the arrests of young people trying to organize economically and educationally, and the surveillance of families who remained. Every sentence I read pained me; these were not just statistics, but broken lives, extinguished hope, and stories demanding to be heard.

In other files, I found reports on the efforts of the Albanian Chams to preserve their traditions, language, and national identity. The Greek administration and local power structures viewed these efforts as a threat, exerting daily controls and violence. A 1960 report noted: “Any cultural activity of the Albanian Chams may be a source of instability. Every effort for national formation must be kept under control; it is forbidden.” These words, written on bureaucratic paper, were for me proof of an injustice I could not ignore.

Every document I flipped through made me realize that violence and persecution were not just isolated moments but part of a system aiming to extinguish the identity of a people. This knowledge deepened my consciousness as an Albanian and made me understand that the history of Chameria could not be forgotten. It was the history of a nation that had suffered but could not be extinguished by silence.

My reflections on these documents were profound: Every note, every report, every list of persecuted families was a call to document the truth and to preserve historical memory. As I read about the burning of homes and the confiscation of land, I thought about the fate of the generations who had endured this pain and the responsibility we had to tell their story.

This consciousness drove me to create a vision for action: to write, to analyze, and to bring to light those truths that had remained hidden in the archives for decades. Chameria, through its painful silence, taught me that history is alive, that every secret document is a part of a nation’s soul, and that the duty of the intellectual and citizen is to preserve this soul for the future.

Kosovo: The Controlled Territory

Kosovo, just like Chameria, was a territory where history and violence clashed every day, but in a more sophisticated, secret, and controlled manner. The archives of the Yugoslav Intelligence Service revealed a bitter reality: the Titoist regime exerted strict control over every political, cultural, and educational activity of the Albanians.

A 1971 file described the surveillance of Albanian intellectuals who publicly expressed themselves about the rights of their people. The notes reported on secret meetings, critical expressions, and discussions in university environments, which the regime viewed as a threat to the state order. Some of them were arrested without a fair trial, faced fabricated processes, and were convicted for actions “against the state order.”

Another 1974 report described the infiltration of agents into Albanian cultural associations and educational organizations. Every activity related to the Albanian language, history, and culture was under constant surveillance. The documents showed that the regime used fear, blackmail, and threats to keep under control every voice seeking to document the truth about the fate of Kosovo.

Reading these reports, I felt a deep connection between the fate of Kosovo and the fate of Chameria. Both territories were part of a larger history of the fragmentation of the Albanian nation, where power and violence sought to extinguish the people’s identity and aspirations. My consciousness, nourished by the experience in the archives, made me understand that every small report, every secret document, had historical weight and that morality demanded that the truth not be allowed to be hidden.

A concrete case that left deep traces on me was the report on a Professor at the University of Pristina, who had organized a lecture on the history of Albanians and the importance of preserving the language. The report described it as “hostile activity” and suggested his arrest. For me, this was more than a bureaucratic note-it was proof of the persecution of knowledge and culture, which clashed with a universal right to learn and to teach others.

The Kosovo archives taught me every day that survival was not just a physical matter, but also a moral one. Albanian intellectuals, teachers, scholars, and ordinary citizens fought to preserve their identity, to document the truth, and to transmit history, despite the threats. This silent struggle to survive was a continuation of the pain of Chameria and showed that the history of the Albanian nation could not be separated from both territories: one had remained occupied outside the borders, the other under regime pressure.

My reflection on these documents was clear: the defense of rights, the preservation of identity, and the duty to document the truth are moral obligations. The history of Kosovo and Chameria taught me that every Albanian, regardless of the circumstances, has the responsibility to keep the historical memory alive and to act for the future.

Philosophical and Moral Reflection: The Law of Murphy

As I flipped through endless files and reports, I began to understand that the secret archives were not simply a treasure trove of information, but a window to reflect on the nature of history, rights, and morality. Every document preserved there taught me that the individual, although seemingly small against power and systematic pressure, had a decisive role in preserving memory and historical truth.

This understanding led me toward the concept of “Murphy’s Law,” a simple yet powerful principle: every righteous action, every attempt to document and preserve the truth, benefits humanity and future generations. In this sense, the responsibility of the individual does not end in silence or fear but in moral action, despite threats and risks.

The archives for Chameria and Kosovo gave me clear examples: violence and persecution could not extinguish the aspirations for freedom, identity, and justice. The Cham people and the citizens of Kosovo, through their sacrifices and courage, showed me that history is not written only by the obvious victors but also by those who document and keep the truth alive. For me, every seized file was a silent lesson on moral responsibility: writing is not a luxury; it is a duty.

The philosophical analysis also taught me that history has many layers: what appears what is officially documented, and what is kept secret. It is the individual’s duty to bring to light what has been hidden, respecting the truth and connecting it with the moral and human consequences. Every report on the violence in Chameria, every note on the persecution in Kosovo, was not just information-it was a call to conscience.

From this analysis also arises a deep conviction: the individual, who acts with dignity and conscience, even when alone against a large system, becomes a bridge between the past and the future. The moral duty is to document, to write, and to transmit the truths, to keep identity and history alive. In this way, the action of an individual is not simply personal; it contributes to the common good, to the recognition and acknowledgment of the history of a fragmented nation.

The humanist reflection also brings the question: What will remain after us? What will future generations inherit? The answer from the archives and personal experience is clear: what remain is the documented truth and the preserved memory, a wealth that cannot be trampled by fear or violence. This is the mission of the individual and the moral truth that guides every writing and every effort to preserve history.

During my years of service in the SDB, there were moments when fear tried to replace moral conviction. The heads of the UDB often reminded me that any step towards publishing secrets could lead to severe consequences: sealed prisons, isolation, and facing unprecedented repression. But as I looked at the files and documents for Chameria and Kosovo, I felt a duty that transcended personal fear-a call to act with dignity and responsibility. / Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue