Part Two

Memorie.al / Hazis Ndreu, born in the city of Peshkopia, is one of the survivors of the Tepelena internment camp. He spent 43 years in internment, starting at the age of 14 in Kuçovë, following his father’s escape to Yugoslavia, and continuing in Berat, Tepelena, Bënça, Myzeqe, Llakatund, Lubonja, and Vlora. His internment ended in 1990, but he spent the most difficult years in the Tepelena internment camp, for which he recounts the tortures, persecutions, and suffering of the internees through work, punishments, sentences, poverty, and lack of food, clothes, medicine, and diseases such as dysentery, typhoid, tuberculosis, and bronchopneumonia. Due to the numerous diseases and deaths in the camp, the command appointed Hazis as a medical assistant (sanitar), and later as the camp nurse (infermier).

Continues from the previous issue

Can you recall any specific episode that made an impression on you as a nurse?

The doctor came once a week to the camp. During this time, we presented the list of the sick. The doctor gave the therapy, and we treated them until the next week arrived. When we had seriously ill patients, we informed the command, but the doctor might or might not come. Emergencies happened every day. But who cared about the internees? Therefore, there were deaths every day. And disease, of course! Dysentery, typhoid, tuberculosis, bronchopneumonia. In the Tepelena camp, I lived with death. I, who was supposed to save those people’s lives, was powerless.

I had nothing to offer them. Neither medicine, nor food, nor clothes, nor warmth, only air. But even the air in that dark gorge without lights was black. One night, a 12-year-old child, sick, was asking me for bread. Where was I supposed to find bread? He had already eaten his ration. After a long pause, he asked me: “Doctor, am I going to die?”! What was I to tell the boy who was only asking for bread?! Hunger was terror. I don’t know, I had medicine for the boy, but I didn’t have bread. Hunger caused devastation, and the boy died of starvation.

During your internment, did you maintain contact with your father who had escaped?

No, absolutely not. Even when we wrote a letter to our people, we had to hand it over to the command in an open envelope. Whether it arrived or not, we never found out. If you saw us at that time, you couldn’t distinguish us from the slaves we’ve seen in movies. To tell you honestly, I felt envy when I saw a documentary about the Auschwitz concentration camps. I saw prisoners there in uniform. We were terribly exposed.

Didn’t you have clothes?

No. We remained with the clothes we arrived in. And who would give us clothes? We worked, and the clothes tore. We patched them up, but they shredded again.

Didn’t your relatives in Dibër, Tirana, and elsewhere help you?

It was very difficult. Packages were registered. There were consequences for the person sending it. Most of the people in the camp had no one. In the camp, besides Albanians, there were also prisoners of war: Germans, Italians, and French. Among them, we had two German girls. After working for some time carrying wood, as there was only wood-related work in the Tepelena camp, one was brought in as a medic in the infirmary, while the other was put in the kitchen.

The one they brought to me was named Amri Shubert. Amri was naked. What were we to do? Together with the other medics, we took away a blanket. We made a formal record (proces-verbal) as if we had sent the blanket with a sick person to Gjirokastër. We dyed this blanket at night with onion leaves. The blanket changed color. We made a sack-like garment, like a cape, and dressed Amri in it. Not a day passed without something happening in the Tepelena camp. Those working in the Bënça mountains threw the logs into the river.

After throwing the logs into the river, they accompanied them to the bridge near the camp. There, they waited for them to pull them out of the river. Once, a log got stuck on the rocks. Someone pushed it with a stick, but in vain. Then the police officer forced the internee to enter the river. It was January, cold. The man who entered the river removed the log from the rocks, but when he came out of the water, shivering and trembling, he fainted. His clothes froze, his face too, his whole body. “He died,” everyone said. I told you, it was January and very cold.

Tepelena has a strong wind, as if it is the mother of the wind. His comrades cut some wood, made a stretcher (vig), and around 8 p.m., they brought him to the camp. They told me: “Open the morgue, he has died!” He had frozen. “Let’s take him to the kitchen to dry his clothes,” I said. So we put him near the fire. We were waiting for his clothes to dry to put him in the morgue. The camp had a large field, about 200 m in front of the kitchen. Everyone was waiting in the field. When I heard a gurgling in his throat.

Those standing near him said the dead man came back to life. They were more frightened than happy. No one approached him. I checked his pulse. “Don’t move him,” I told the people. I went to the pharmacy and got 3-4 caffeines for his heart. I quickly administered them, and his heart started working. That is how Kel Gripshi came back to life. In the morning, as soon as he opened his eyes, Keli was asking for bread. Since that time, only a small portion is still alive.

Only they can confirm how we went to work and when we returned from work in the evening. Only they can affirm how often they were ordered: “You must set off for Salari because a truck with wood has been left behind.” Imagine where Salari was? They set off, load the wood themselves, and arrive at the camp at dawn. They had worked all day, they had worked all night, and in the morning, they had to line up again before the command.

“We won’t go to work anymore,” some women said. “You will go,” the command ordered. “No,” the women said, “we will all die here and we won’t go! We have worked all day, we have worked all night, and we have no strength left!” Because they resisted, they were tied up and left in the middle of the square. Some were put in solitary confinement (birucë). They were left in front of the command all day.

Did you ever try to leave the camp?

No, never! I didn’t know any route. I didn’t know where to go. I couldn’t walk even one kilometer outside the camp. Once a sign had fallen, and a police officer told us: “Did you knock it down?” “We didn’t knock it down,” we told him. He took both of us and put us in solitary confinement. While sitting there in the dark, we noticed that someone was hanging by her hands. This was Shega Frashëri. For as long as we were there, we took turns sitting down and holding her on our backs.

Was she alive?

Yes! They had hung her by her hands. The officer who had hung her knew how long she could resist. When he opened the door, we let her down. When he saw us, he told us: “You here?! Out now!” I want to talk about the help given by the doctors who came to the camp. They were free people. Initially, we had Doctor Hazika, then Doctor Lluka Dhimolea. I was very young and didn’t know much. As I grew, I learned from them. I often told the doctor: “Assign this diagnosis, because if we don’t keep him here, he will die working.”

We saved people through Doctor Dhimolea. On the surface, he seemed very harsh, but in fact, with what he did, he eased our wounds and helped us a lot. When I told him; “Doctor, assign this diagnosis so he doesn’t have to go to work,” he accepted.

Why did you do this?

To save them from the suffering of work, even for one day, so they could recover. They were beaten so badly that they brought them to the infirmary on a stretcher. That is what happened to Hasimeja. She suffered from epilepsy (sëmundja e tokës). While going to work, she had an epileptic seizure on the way. The police officers, because she broke the line, kicked her. An epileptic person cannot hear while in crisis. They left her there. The others continued on their way. After coming to, the sick woman could no longer get up; she had been beaten so badly.

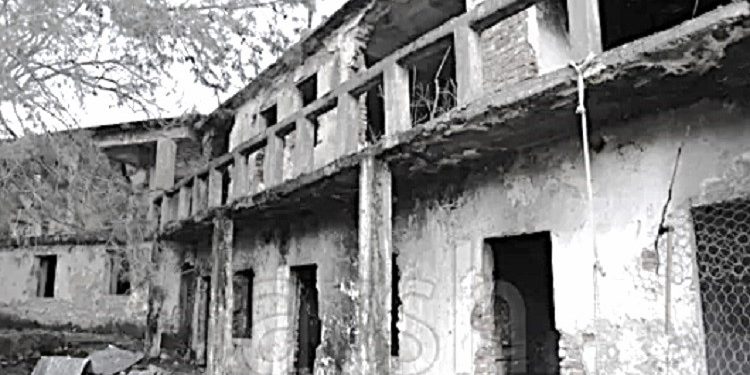

They took her and brought her to the infirmary. Her whole body was covered in hematomas. I was surprised and scared. “What kind of illness is this?” The one who brought her to me said: “The sergeant.” I understood. Revolted, I went to the command and told them: “Figure it out, because I can’t do anything for Hasimeja. Either send her to Gjirokastër, or leave her here to die.” Thank God that in 1954, the Tepelena camp was closed.

Can you single out any story that left an impression on you?

I return again to the Tepelena camp, where none of us ever thought we would get out alive.

Why?

Death every day. Without food, without drink. Hard, tiring work. 20-year-old boys looked like finished old men. When we saw death every day, we thought we would die too. One day, an Italian told me: “Save the Major, because tomorrow the police officers have sworn to kill him.” And I told the Major; “Don’t go out to work tomorrow! Tell them you are sick.” But the Major, an officer of great culture and with an enviable character, told me: “How can I lie? I am not sick!”

“I am telling you that you are sick, and tell the police officers the same. Your states will ask for you and take you with them. Save yourselves for us. When you leave, tell them what happened here.” – “They will call me a liar,” the Italian replied. – “If I survive, no one will believe me if I tell them what is happening here today, as it is unbelievable. When I leave here, no one will believe me. If I speak, they will say he is crazy.”

In Tepelena, the most terrifying thing was the loss of the graves. Three times we buried and exhumed the dead. In the end, all the graves were lost.

Did it not cross your mind to have a romantic relationship (bëje dashuri) with the German nurse?

We had forgotten what we were. Whether we were human beings or logs. Under those conditions, with the treatment we had, with the life we led, we had lost everything. The only thing left to us was solidarity. We called all the women sisters, and they called us brothers. The thought of such an act did not cross anyone’s mind. It was an absurdity to even consider such a thing. / Memorie.al