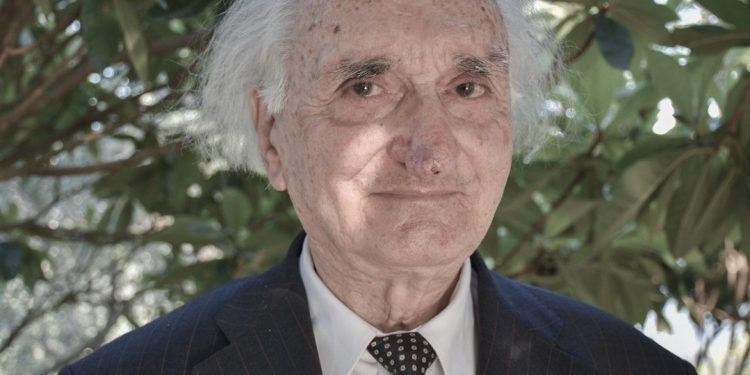

From Lek Pervizi

The first part

Memorie.al / That morning, as soon as the light had started to come out, in the four cyclopean barracks where my crew and I were interned, the deafening metallic bangs of the bags, the brass shells of the guns, which were hit with iron rods, sounded all at once. The deafening thunder spread through the gorge of Vjosa, terrifying the surrounding mountains and the fortress of Ali Pasha Tepelena, which cast its black shadow over the internment camp created nearby by the communist regime of Tirana. The convicts woke up dazed from that sleep, which at least gave them some peace from their daily torments. The roar of the can was accompanied by the hysterical calls of the person in charge of each barracks: – Wake up! Appeal! Get up fast! On appeal, on appeal!

This scene, which was repeated every day, also happened that morning at the beginning of December in barracks No. 1 where I was locked up with more than six hundred other innocent creatures. The crunch of the bag had brutally woken me from sleep. My heart was pounding. I did not hear without muttering some swearing among the dhams. Banal words of men, curses of women, and wails of children and complaints of old men could be heard from all sides.

A commotion was created that filled the space of the giant hangar, a great noise: fairies, cries and cries of the intenuems who had to get out and get off the two-story wooden frame that served as a bed. People had to come around to get out where the appeal was made. When their name was called, they had to answer “here” and pass in front of Captain Selfos, the terror of the camp. As long as the canga was silent, Pretashi, a large and responsible mountaineer from the barracks, who was also interned, continued to call out in his baritone voice:

– Quick, quick, everyone on call! All in appeal…in appeal!

Next to him stood Captain Selfo, short and stocky like a poorly carved oak stump. They dress him in police uniform, with a tuft of gray hair sticking out of his hat over his narrow, ruddy forehead. Under the nostrils of the press, there was a pair of mustaches like brushes, yellowed by tobacco smoke and the smoke of brandy. He was holding the appeal register.

His short fingers resembled the stoppers of vein bottles. Pretashi, close to him, like an electric pole, stood ready with a lantern in his hand, so that he could read the names lined up on the yellowed pages of the register. Because the three 40-watt lamps that hung from the trusses of the roof had no power to illuminate that cyclopean barracks.

The light of the lantern focused on the faces of the two characters. The internees moved in the darkness like a frog. The scene was worthy of Rembrandt’s brush. The captain was perched like a rooster on manure, resting on two bendy legs, inside a pair of boots with worn heels that had never been polished. A revolver hung at his side, like a cowboy in the movies.

He began to pronounce the names of the condemned, one after the other, as if they were the verses of Homer or Dante Alighieri, whose names he did not know nor their deeds. The one who heard the name should answer “here” and pass in front of Selfo, who gave him a disapproving look under his black and thick eyebrows.

– Mrika John! He called out the first name with that thick, crooked voice of his. It was the first name of the long list, with which the appeal in barracks No. 1 began.

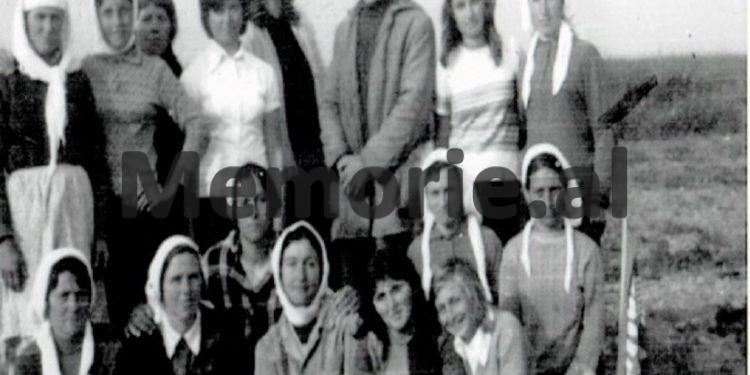

– Here, answered mother Mrika, my 70-year-old aunt, passing in front of the captain, followed by two nieces and a nephew, whose names were read. Mother Mrika, was the wife of Gjon Markagjon, the captain of Mirdita, we interned her as early as 1945 by the communist regime, after their houses were burned, looted and their property confiscated, as had happened to our family and other families of the same family rank. The recitation of the names continued with the same “poetic” rhythm.

The captain sometimes called the internees only by their first name without their last name, as if to relax from the long reading: Kel, Gjosho, Karlet, Pina, Marie, Suzana, Ded, Filé, Prena, Gjela, Dila, Zef, Nikoll , Tom, Selim, Ferid, Hasan, Hava, Bukurie, Dudie, Caje, Elena, Evgjen, Mark, Frrok, Llesh, Gjin, Zorka, Giuliana, Angelina, Mara, Nimçe, Zana, Age, Djella, etc., until a lighthouse when he called:

– Chest! Silence. No one answered.

– Chest Kadeli! Silence.

Capter got nervous and turned to Gjoka’s sister-in-law, Mrika:

– Why do not you answer? – He spoke angrily to the desolate woman who was standing in front of him bowed and with tears in her eyes.

– Yes…yes…Mr. Captain…Gjoka is sick tonight.

– Uh..uh! …So I’m dead…?! It’s good to become…one enemy…one less dog! Said Selfo, grimacing as he looked at the pale faces of the internees who had remained oblivious and powerless to the insolence of the captain. How was it possible to laugh and scold and insult a dead person?

Mrika left without saying a word. The appeal continued. Those who passed ran to their places to protect themselves from the cold. There were those who were touched by the vile behavior of the captain, whom they cursed. But in his presence, no one dared to say a word. There was no joking with him, of the hunchback and rope as he was. After a while it was my turn.

– Lek!

– Here! I answered and passed me. He gave me a blank look.

– Stop! He said, don’t show me those hands!

I spread my scarred hands in front of his eyes, twisting them. The wounds were bleeding. He looked at them, pursing his bulldog lips, addressing me:

– Look. The doctor is coming today. Yes, he didn’t give you a report, there at work with your friends. Do you understand? Come disappear!

I left, passing in front of Gjoka’s funeral, where I met his sister-in-law and a couple of his cousins, who were looking after him. Then I started my layers, where I snuggled up and warmed up a little. The cold was too bitter. The barracks looked like a large refrigerator. Gjoka had been dead for two days, but the women had kept him hidden there under the veil that the Mirditors called “postahe kmene”, made of goat’s fur, to benefit from the bread ration. Bread was the most precious thing in that camp, where people suffered and died of hunger. In his last agony, the deceased Gjok had asked for his ration. In those last moments, he kept the bread behind his chest, like a holy relic.

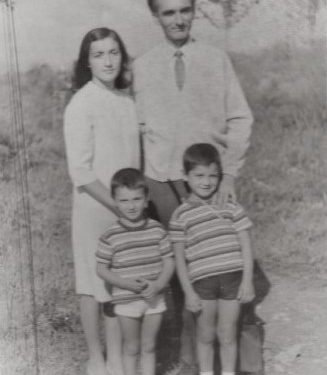

The internees were overwhelmed by the idea of a lack of food. Gjoka was neither the first nor the last to die of hunger, torture, hardship, cold and disease. In my mind, I remembered my ninety-year-old grandmother, my mother Mrikëa, who was called “Little Mother”, who had died in that camp, exhausted from suffering and illness, next to my young mother. How many other old men and women lost their lives in those miseries! Her death was even harder for me, because I wasn’t exiled yet, and I was held hostage all my life since I grew up with her boundless love.

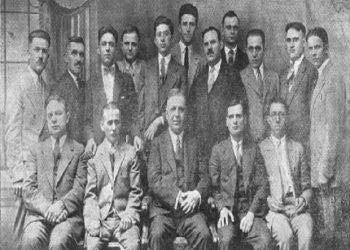

But Selfo was not the only camp executioner. He was followed by other comrades of the same mold, starting with the commander, Lieutenant Xhaferr Pogaçe, who could neither read nor write. His deputy, Marshal Syrjaj, of the secret office, very insidious and dangerous, and in turns the captains for each barracks: Koçiu, Tomi, Hyseni, Mihali, etc. Likewise, the sergeants who accompanied the internees in the mandatory work: Qaniu, Duro, Kamberi, Sako, and others. All the criminals in your region, one is better than the other. I listed their names so that they will remain forever branded.

I had run to my layers, where I hunkered down to escape the great cold. When I went to the appeal, due to the haste I had not thrown my old coat over my arms, so the cold had penetrated to my core. From there I could see the movements of people, and the place where Gjoka’s funeral was, a few dozen meters away.

I couldn’t sleep anymore because of the worry that the captain’s words about the doctor had caused me. Medical report! Damn work! Meanwhile, the short-legged captain, Selfo with the giant Pretash, had stopped in front of the burial place. They took a look at the body covered with a blanket and the people surrounding it, all of them elderly, who included most of the internees.

– To be buried this afternoon, did you hear? The captain had spoken before he left. The people had left haru. No one moved or spoke. Pretashi, behind the captain’s back, with his finger on his lips, signaled them not to object. Once they passed, the internees came to say their last goodbyes to their fellow sufferers. After all, their friend had escaped the sufferings and tortures of this earth and of Captain Selfos.

When the camp commander was informed, he postponed the burial until the next morning. Because even in barracks No. 4 an old woman from Kukës died. Four workers were assigned to open their graves on the bank of the Bênça River and to prepare the coffins for the transportation of the funerals. The graves of the internees were set above the Bênça Bridge, a couple of kilometers away, where they were transferred from the field in front of the camp, a year ago.

That field was filled to the brim with ravines, which had begun to open from the side of the mountain, at the foot of the road leading to Gjirokastër. The dictator himself spent one day there.

– What is this job? What are these graves of internees at the foot of the national road? They disappeared! Don’t miss one when I pass this way again!

In the transfer that was made to Ura e Bênça, many graves remained untransported, because the relatives of the dead were released or sent to other labor camps. For our grandmother, thank you for being our mother Mrika and some of our cousins, who took her relatives to Bênça. We were scattered without days for each other. As soon as the transfer of those few graves was finished, one put the bulldozer and the tractor into the field, to eradicate every sign of the grave and one planted it with oats. So most of the graves disappeared forever.

The wounds on our hands were caused when we were interned with our older brother Valentin and others; we were taken to a Special Department of the Ministry of the Interior. We were a group of 10 people, considered the sons of the most dangerous fugitives abroad. They had put us in a sheep shed so low that we had to move on crutches. Darwin would have liked this change of man into a four-legged animal, which suited his theory.

They forced us to work even when it was raining, but it was impossible. The guards, they were also forced to stay under the rain. Then they allowed us to light a big fire, around which we sat to tell them that we were porridge. A cold rain almost turned to snow. As we got dry on one side, we got wet on the other and vice versa.

Once the rain stopped, they started us straight into the forest, above the steep and rocky mountain, where we could barely climb. Under these circumstances, my hands were covered with some strange wounds. I couldn’t hold anything in my hand, not even an axe. My friends laughed.

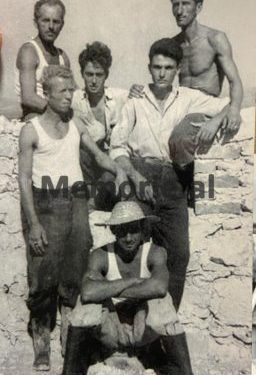

– Lek, yes, these are stigmata like Christ’s. You are becoming a saint…! Ora pro nobis….miserere nobis…! Pray for us, have mercy on us and save us from this hell… Saint Leka! It was really to laugh at the other person’s misfortune, which was me. In that hut, as I said, several fathers’ sons had gathered us, where, along with me and Valentin, there were: Viktor Dosti, Fatbardh Kupi, Tomorr Dine, Avni Agolli, Bexhet Ndreu, Abdurrahman Kaloshi, Reshit Mulleti, and about ten men mountain slopes.

Everyone laughed except me. I was worried. What is happening to me? Valentini tried to calm me down. He had military experience and had fought against the Germans. He knew the bad conditions of military life and what the wounds were. The commander of the department was a certain Sergeant Lulo. A grumpy and tough man. He had seen me not working and that I had rested the ax on the trunk of the oak that he had assigned me to cut down. He was angry.

– Hey, you prince over there, grab the ax and give it to your arms. It’s no longer the time of your general, when you were wandering around schools abroad!, – he called, pointing the machine gun at me.

– I’m dying, but they don’t wash my hands. Don’t look once! – I said, holding out my bloody hands. With all his nerves he approached, and when he saw the condition of his hands, he went away shaking his head, while muttering to himself, cursing Captain Selfon, who had brought him such an incompetent spree. The next day, Sergeant Lulo, escorted me to the camp himself, there in front of Capt. Selfos. I was tired and out of breath and threw the den of loot on the ground in front of the non-commissioned officers. Captain Selfo gave me a wild look, but Lulo didn’t let him speak:

– Listen, friend Selfo, I don’t need these sons of aristocrats and sons of morons and cripples. Do you understand or not? I need strong and healthy workers, who know how to use a spade and will not be wasted like this one, who does nothing! – Sergeant Lulo was venting, they are all angry.

And Captain Selfo, not bothered at all by Lulo’s words, frowned revealing those horse legs yellow from smoking. But seeing my bloody hands, he was surprised:

– Uh, uh!…What are these wounds?! Why did you leave them unconnected?

– With what? – I replied sharply.

– Listen, you son of the general, because I am in command here. March straight to the barracks; don’t play from there to save your skin…! Take the spoils and disappear!

I was assigned a night guard inside the barracks, together with a crippled mountaineer, Ded Pjetri, from Shkreli. For two months, no one bothers me. The wounds lay open and strangely bleeding, as in the slaps, on the backs of the hands, up to the pulse, and nowhere else on the body. No one knew and they gave him an explanation. Only an old man who was known as a popular doctor, a 70-year-old man from Kurbin, Ndrec Prenga, calmed me down.

– Don’t be upset that they have passed me in time. There is no cure for them, but its fine, I kept them in the sun. Do not tie or touch them. But from this evil, you have escaped from the work where your friends, tired and exhausted, fall victims, like the Deserted Chest. The old man was telling the truth. My physique could not withstand those hardships. The hand wounds were life-saving. Go and give an explanation! Pretashi, as the in charge of the barracks, participated in the meetings with the command. He, who was kept as a spy, had told me that it was for those wounds that had not disturbed me, but be careful, that he should go to the doctor. If the doctor didn’t give you a report, you have a bad job.

It had been three months since the doctor had appeared in the camp. People expressed wonder about my wounds, which had also affected my physical weakness. Women, when I happened to pass by them, showed me respect and their eyes shone with tears of compassion, for this young man they were so bad, a shadow of themselves. And the doctor was coming! I had received the order to show up for the medical visit. That was where my fate would be decided. If the doctor doesn’t give me a report, how would my situation be? I felt myself dying just thinking about that job. All my concern was focused on those wounds, and I had no idea how, I was physically sick. I saw them. Unshaven. With long hair and a pale and faded face.

Not at all aware of my condition. So they are plagued by a deep sadness, I sit and gather my legs and hands under the covers, where I had found some warmth. When lo and behold, the bell rang, alerting the workers for bread and a sip of tea. The kitchen was located about 100 meters away, across the field, between the barracks. Attack! Almost the majority, once they got the bread ration, ate it on the spot, with every sip of tea, staying all day with a dry stomach.

They had not yet returned to the barracks when the work bag fell. All those who were able to work, from the age of 15 to 60, still with their clothes soaked from the previous day’s rain, were forced to appear in front of the offices, for the job appeal, woe to the one who was absent. The appeal was made by the almighty captain Selfo himself, who also shared the work. Some for wood. Some for stone slabs. Others for mining poles.

From morning to night, without schedule and without rest, and without food. Was it raining or not snowing? This is how the workers were sent as a horde of people, men and women, to be tortured and tormented as the communist party and government had decided, with the aim of subduing them, exhausting them, turning them into slaves and working animals, and to lose the name and honor of their families, to turn them into living beings of no value, nothing.

With the departure of the workers, the barracks became empty and remained with women with small children, old men and women, some sick, like my work, and some dead, like Gjok Kadeli and that old woman from Kuksia. Not a week went by without one or two of us being interned.

So, around Gjoka’s funeral, several elderly women were gathered, who were weeping softly. The command had stopped the wailing of the women as was the custom. In this case, they had left someone to guard against any captors. The mourning was stopped, because in their words, the mourning Albanian women made a biography of the deceased, but also mentioned the sufferings that he suffered during prisons and exiles from the communist regime, as shown in the following example that I have memorized:

« ….We have received a government without emea

Half male and half female,

On the tip of the tongue is the root,

Burn his back and cut down the tree.

Who is killing and imprisoning men,

Interns people with turds,

Interns our families,

Old and old, children and nana,

Woe to the Albanians, what has he found?

I suffer a lot and I take a lot!

……………………

Enver Hoxha be damned,

Elderly and children in the stack camp!

Men and women, mothers, children,

Like cattle locked in a wire,

As in the ear, where cholera falls,

Children and old people die like flies,

To be buried by the lights,

You have filled this earth with graves,

On the banks of the streams they were completely lost,

The government really hounds.

Or Enver has no faith and no God!

May you be cursed for life and death?

Curse the desolate nannies,

For the children who lost their lives!

These death elegies were whispered by women, and contained in their verses expressions denouncing the terror that was exercised on innocent human beings. The sun was rising over the mountains and the day was breaking, when the laborers set out for their grueling work. That day, the sky was clear and the weather was beautiful, but it was very cold. Everything had frozen, even the hearts of the poor internees, under the weight of the camp’s terror and misery. Then the sun began to pour its hot rays through the windows that gave light to the barracks.

A window was directly above me, and I took advantage of it by feeding my body with those warm, life-giving rays of light, turning my back to absorb their heat. From that window I glanced at Ali Pasha’s castle, under whose black shadow laid the camp. Later I will draw a pencil drawing on a piece of paper. I returned my wounded hands to the sun’s rays, as old man Ndrec Prenga told me. The wounds seemed to burn, and some bore blood like pinholes. As soon as one dried up, the other one opened. Something really strange. Among these thoughts, except when the cleaning bag, which was worn by women with children under five years of age, who did not take them out to work? They had to clean the barracks.

– Cleaning! Pretashi called, walking through the corridors between the scaffolding. He called the women assigned to that job by name: File, Drane, Zorka, Vidra, Zoja, Prena, Milka, Djella, others. Her one complained, the other protested Cursing Word. Pretashi was nervous. The women laughed. In the end, everyone agreed and the cleaning began with big pine brooms, after they had sprinkled the land with water. There was the sound of brooms rubbing against the concrete floor, accompanied by the cries of the reeds playing inside the barracks because they couldn’t get out of the cold. Some elders were gathered around the lifeless body of their suffering friend. Gjok Kadeli was the youngest among them, but the frequent tortures he had suffered, the hardships, the hunger, the cold, made him suffer until he died prematurely.

The command did not interfere in these ghanas and allowed the internees to perform the funeral rite, but in silence. Rather, it was the women who were engaged in that work. Gjoka’s funeral had been placed in a shack they had built with wood, the workers who were assigned to open the grave. The corpse was covered with a couple of meters of white meringue, which in such cases was given by the command. Memorie.al

The next issue follows