From Bashkim Trenova

Part twenty-five

MYTH-MYSTICISM, VICTIMOMANIA, RACISM AND SERBONOSTALGIA

ALBANIANS ACCORDING TO THE SERBS

(THE EASTERN CRISIS AND THE BALKAN WARS)

Memorie.al/ “Serbs are descended from the Slavs, a large number of tribes that gave birth to the Slavic peoples. Knowledge about the origins of the history of the Slavs is modest and not so clear. Their name appears for the first time in the 6th century AD, when Byzantine writers start talking about the Slavs….”! (Dushan Bataković, Milan St. Protic, Nikola Samardžić, Aleksandër Fotic. History of the Serbian People. L’Age d’Homme. Lausanne. 2005. Pg. 3.)

Continues from last issue

Sava Andjelkovic – Lecturer at the University of Paris I-Sorbonne, in the Department of Slavic Studies:

The Battle of the Black Bird Field (Kosovo polje), near Pristina, on June 15, 1389, is deeply embedded in the consciousness of the Serbs. The outcome of the battle remained uncertain even after several months. At first, the Turks were stopped in their advance, which seemed to be a victory for the Christians, but very soon the heirs of Lazarus recognized the Turkish power and became its allies.

This historical event, which marked the beginning of the end of the medieval Serbian state, turned into a legend, becoming a metaphor for heroism and treachery, legality and illegality, sacrifice and the choice of the heavenly empire instead of the earthly one, which is really the central idea of the tradition related to Kosovo, present even today. The legend and the epic version of events were, of course, more seductive and powerful than the historical facts. Meanwhile, the Serbian public is anesthetized by continuous stories, according to which Kosovo has been lost for a long time. All of our Atlantean elite participate here in their own way:

No original text of a song about the battle of Kosovo, dating from the 15th century, has been preserved; the oldest document dates from 1530. Miloš’s heroism will be present in popular tradition only starting from the second half of the century all fifteen, as it seems thanks to Ottoman written sources (Popovic 1998: 42), which mention him for the first time under the name Bilish Kobila, as the treacherous assassin of the Turkish emperor. Vuk Karaxhic published in 1823 Fragments of various songs from Kosovo, a title which suggests that they were remnants of songs lost in their entirety.

All are in ten-syllable strings. The first narrates the arrival of the Turkish emperor Murat in Kosovo and the letter he addresses to Lazar, where he invites him to either surrender the country or faces him in battle. The second contains the curse that the prince gives to all the Serbs who would not come to fight in Kosovo. The third, central and essential, although quite short (63 lines), sings of the dinner given by the prince on the eve of the battle, uniting the main Serbian participants in the battle.

The fourth shows a vanguard charged with the task of assessing the numerical importance of the Turkish forces, and the fifth depicts the heroic behavior of the main heroes during the battle. These fragments, which Vuk Karadžići rewrote as he had heard them sung by his father in his childhood, were undoubtedly composed; in the form we know them today, from the end of the 18th century. Vuk Karadzic, who although collected many epic songs during his travels in the Balkans, never managed to find other storytellers capable of singing the same lyrics or at least variants of them. (1)

****

Slobodan Antonič – sociologist, political analyst, professor at the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade…:

Nikola Hajdin (former president of the Serbian Academy of Science and Arts-SANU): “these people should get used to the era when Kosovo was lost”.

Vladimir Kostic (current president of SANU): Kosovo is not ours – and this must be understood as soon as possible” that “neither de facto nor de jure is in the hands of Serbia” and that “in at this moment, the only political ingenuity with elements of dignity is to release Kosovo”.

Dubravka Stojanovic (for RFE): “Serbia cannot move forward until it has faced the fact that Kosovo is lost in the war.”

Biljana Srbljanovic (Blic): “There is no possibility that Kosovo is “ours”, that’s all”.

1 – Sava Andjelkovic. Les motifs du chant populaire Le Dîner du prince dans la piece de Ljubomir Simović. The Battle of Kosovo. (Motives of the popular song Prince’s Dinner in Ljubomir Simović’s play. Battle of Kosovo). Revue des Études Slaves. LXXXIV-1-2/2013. Pg. 9-24.

Alexei Kishjuhas (Danas): “Kosovo, practically, is independent and this is a reality.”

Snezana Chongradin (Danas): “Kosovo’s independence is the only acceptable compromise”.

Srdjan Dragojević (on Twitter): It’s stupid to follow me if you don’t agree with my postulates: 1-Kosovo is independent; 2-Genocide took place in Srebrenica”.

Dejan Ilic (Pescanik): “I was more struck by Novak Djokovic’s exclusion from the tennis tournament in New York, than the possibility that Vucic signed Kosovo’s independence in Washington a few days ago.”

Bojana Maljevic (for H1): “Kosovo is independent, regardless of whether or not it has a seat in the UN.” (On Twitter); “The opposition lies to the people by saying that Kosovo has not ceased to be ours for a long time.”

Vladmir Arsenijević: “Is Kosovo really Serbian?” I wouldn’t say that. I think Antarctica is probably part of Serbia, but that doesn’t help me at all.

Bojan Toncic (Remarker): “Kosovo is not Serbian…”.

Gordana Susha (Danas): “… a phrase about the “most expensive Serbian word” (…) that pumps up and revives (…) a warmongering nationalist opus.” (1)

****

Slobodan Dukić – historian:

I remember well the days of my childhood and the fear of Albanians. “If you are not good, the Albanian will kidnap you”, my mother used to tell me threateningly. As soon as one of us saw a man with a chainsaw slung over his shoulder, he thought he was in “danger.” Then we all hid behind the bar overlooking that side, waiting for the saws, as the adults called them, to leave the corner of the street. I heard old people saying that “they” are for nothing but sawing wood, transporting coal, dirty work. Decades have passed and we still hear about Albanians that they are inferior beings. Aggressive fans in stadiums have turned tolerance towards neighbors into hatred. Blinded by hatred, he repeats the refrain: “Strike, massacre, so that the Albanian is annihilated”!

Thus, it cannot be said that the history of these relations is enmity. There were moments of conflict, but also of friendship. Since the Slavs came to the Balkans, they have lived with the Albanians. Together they belonged, as a part, to several large multinational states: Byzantium and the Ottoman Empire. There was no conflict until the 19th century. Neither the Serbian nor the Albanian people at that time intended to create large states.

Tensions in relations arise with the beginning of the creation of national states in the Balkan geographical space. The maps of these mega-states overlap and extend over the Albanian space. Albanians are late in creating their state. It was created only in the 20th century. But there are already nation-states that have appropriated their living space… The Albanian national movement appeared with the League of Prizren in 1878. It was a call for Albanians to unite and have a national program, which will lead to a single ethnic state. The intention to have a national idea and to lay the foundations of the state causes resistance in other Balkan nations. They see this as a project for a great Albania. (1)

1 – Slobodan Antonic: Nos lignes rouges – les enfants et le Kosovo. (Our red lines – children and Kosovo). Srbin.info. 26.09. 2021.

2 – Slobodan Dukić. Mali mit o testerasima i veliki o “Staroj Srbiji”. Un petit mythe sur les testeurs et un grand sur la “Vielle Serbie” – A small myth about the testers and a big one about “Old Serbia”. Pancevo-City. 26.02.2018.

****

Srđa Popović – political activist, one of the founders and leaders of the Otpor Student Movement:

And it seems to me now, when I look back at all this, that we have come full circle, and it seems to me that this policy of force has led to a complete defeat. And I dare say it, even though I know it’s not popular – Kosovo will never be part of Serbia again, except in case of a Third World War. (1)

****

Stanislav Sretenovic – professor at the Institute of Contemporary History:

The first attempts at regional cooperation resulted in the conclusion of bilateral agreements of friendship, defense alliance and military cooperation between the Balkan countries, with the aim of liberating and uniting their compatriots still under the tutelage of the Ottoman Empire. On the initiative of the Serbian prince Mihajlo Obrenović (Mikhail Obrénovitch), a series of agreements of this type were signed in the years 1866-1867.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the alliance made by Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria gave them the military victory against the Ottoman Empire and allowed them to expand the national territory, the formula so dear to the Balkan politicians of the time, “Balkan for the Balkan peoples”, rather it meant the hegemonic effort of this or that people of the region, the high dignitaries of the Church who bless murderers, promote criminals to sanctity, protect pedophiles, do not pay taxes, spread hatred towards other nations and religions. (1)

1 – Srdja Popovic. Osveta Kosovo. (Kosovo’s revenge). Radio Pescanik. 22.02.2008.

2 – Stanislav Sretenovic. À la recherche de l’Entente balkanique en Serbie: réflexions historico-politiques sur les années 1930 et 2000. (In search of the Balkan Entente in Serbia: historical-political reflections for the years 1930 and 2000). Anatoly. 1/2010. Pg. 71-86.

****

Stasha Zajevic – peace activist and head of the “Women in Black” organization:

****

Vesna Pesic – sociologist, politician and diplomat:

The Serbian people, like all the other peoples of the Balkans, have built their identity on the feeling of revenge against the injustices done to them. Over the centuries he has been subject to an imperial administration, he has struggled to preserve his identity (language, religion), he has dreamed of a renewal of his lost medieval empire (2)

—

Revenge, according to the myth of Kosovo, derives from two perceptions that the Serbian people themselves have about it: the martyr and the heroic, the victim and the true victor. Revenge of the victim was the basis of the aspect of national identity chosen at a time when circumstances demanded that something be done to cure the “tragic condition” of the Serbian people. Speeches on “vain sacrifices”. (3)

1 – Stasha Zajevic. Lični problem Radmile Hrustanović. (Problème personal de Radmila Hrustanović – Personal problem of Radmila Hrustanović). Radio Peščanik. 26/10/2007.

2-Vesna Pesic. La Radiographie d’un nationalisme. Les racines serbes du conflit youugoslave. (The radiography of a nationalism. The Serbian roots of the Yugoslav conflict). Les éditions de l’Atelier. Les éditions ouvrières. Pg. 36.

3 – Right there. Pg. 37-38.

****

Vladan Jovanović – scientific associate, lecturer in specialized postgraduate programs in the field of mediation at the Faculty of Political Sciences in Belgrade, lecturer, etc.:

If we analyze the results of the Serbian historiography on the colonization of Kosovo, knowing that the ethnic structure of Kosovo had constantly changed in favor of the Albanians, we can conclude that the colonization, which took place between the two wars, was an attempt to correct “historical injustice”.

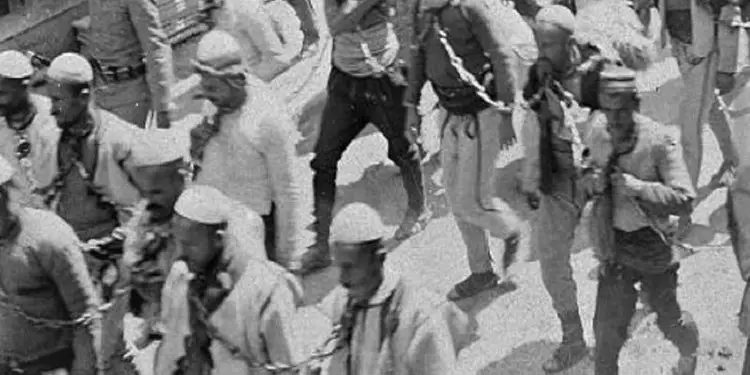

Displacement of “people of Turkish culture” – After the Great Eastern Crisis at the end of the 19th century, a large number of non-ethnic Turks, guided by their religious feelings, experienced the fall of the Ottoman Empire as their personal disaster, and therefore chose to emigrate to Turkey, seeing this country as their true homeland.

The Balkan Wars, the final decline of the Empire, World War I and the creation of the Yugoslav state accentuated these demographic changes. The predominant reasons for emigration were “religious fanaticism”, as it was called at the time, which forbade Turks to live under the rule of “infidels”, as well as family ties, fear of reprisals for participating in the war on the side of the enemy, but and hope for a better life in Turkey.

It is a fact that after the Berlin Congress of 1878, the Albanian issue did not stop developing and internationalizing. The Turkish authorities had serious problems with the Albanians of the Kosovo Province, while their tax collectors regularly avoided Drenica. On the eve of the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the so-called Young Turk regime offered Albanians very specific concessions in education and self-government.

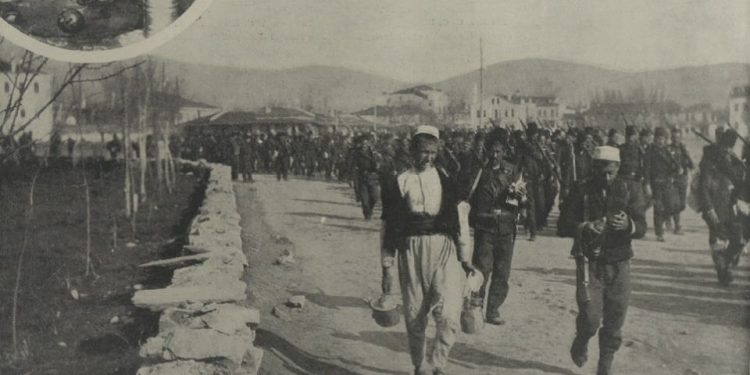

A few years later, the Serbian and Yugoslav states did not offer such concessions. On the contrary, they showed an unwillingness to abandon the irrationality of a myth, and to recognize the new reality. Five centuries passed and things were no longer the same in a demographic sense. The way the Serbian army entered Kosovo in 1912 (by war) seems to have cemented this epic path. (1)

—

If the results of the Serbian historiography on the colonization of Kosovo are analyzed, it can be seen that the colonization that took place between the two wars was an attempt to correct “historical injustice”, given the belief that the ethnic structure of Kosovo was constantly changing in favor of the Albanians from the end of the 17th century until 1912.

What is noticeable from the available archival documentation is the intention to populate this area “with meritorious and nationally verified elements”, i.e. with war veterans, Chetniks, policemen, border guards, refugees and party activists, although some of the colonists were also retired government officials, failed merchants and adventurers.

From the point of view of the state, Yugoslav colonization was “the freest”; each emigrant family was given 10,000 dinars, while for example, at the same time each colonist in Canada received 160,000, in Prussia 120,000, in the Caucasus 90,000 dinars. This is why the people who immigrated to Kosovo, Metohija and Macedonia were overwhelmed with debt, which was partially resolved by the government led by Milan Stojadinović, by paying off most of their debts (80%).

Once settled, the colonists were exempted from state taxes for a period of 3-5 years, while the state provided free transportation and construction material. They were given mainly uncultivated state land, abandoned by the displaced (almost a quarter of the land fund was “property without owners”), and land that had been seized from the Albanian rebels – the Kachaks.

Only in the territory of the agrarian office of Peja there were almost 10,000 hectares of so-called kachaka land. The distribution of land on the basis of political criteria was not the only problem that made the colonists feel uneasy. They lived on unregistered lands, which have changed hands many times. This made them prime targets for blackmail, especially before municipal or parliamentary elections.

The Albanian peasants and the Turks of the city perceived the colonization as a national threat, while the local authorities, for their part, viewed the colonists with distrust. On the other hand, the colonists were a convenient tool to threaten the local population, Milorad Vujicic, then Minister of Internal Affairs, believed that Serbian colonists should only be settled in areas that were under heavy attack by armed Kakachs. A similar point of view was also held by Vasa Čubrilović, who proposed the colonization of the entire area bordering Albania. (1)

1 – Vladan Jovanovic. The colonization of Kosovo. (Colonization of Kosovo). Peščanik.net, 08.04. 2013.

—–

The League of Prizren (for the protection of the rights of the Albanian people) was a movement formed in the same year as a reaction to the decisions of the Treaty of Saint Stephen, which gave the lands inhabited by Albanians to the Slavic states. The basis of the idea of the program presented in Prizren is to merge the four provinces of the Ottoman Empire (Janina, Shkodra, Kosovo and Manastir) into a single Albanian province. Ljubodrag Dimić believes that the League was an instrument of Turkish foreign policy and that the mentioned programmatic document was a kind of territorial and ethnic concept of Greater Albania.

Simultaneously with the Conference of Ambassadors in London, in December 1912, which ended the First Balkan War and during which Albania was first declared an autonomous state under the Sultan, the Serbian army entered Albania. In Albanian historiography, this is considered the “first invasion” of the country by Serbia. In the textbooks of Serbian history, this “goal of the public state war” for the exit of Serbia to the Adriatic Sea through northern Albania, is not mentioned. He, as Dubravka Stojanović notes, is not even mentioned in the textbooks dealing with the First Balkan War.

1 – Vladan Jovanovic. The colonization of Kosovo. (Colonization of Kosovo). Peščanik.net, 08. 04. 2013.

Serbian diplomacy has unsuccessfully tried to convince Europe that the Albanians are not at all mature to have their own state and that Serbia’s withdrawal from the Albanian borders has closed one of the “vital directions of development”. At the same time, Serbian public opinion was saturated with negative stereotypes about Albanians.

This “logic of regional imperialism” includes Jovan Cvijic’s view of the “anti-ethnographic necessity” of Serbia’s exit to the Adriatic through Northern Albania, regardless of the Yugoslav population of those regions, which he considered a Serbo-Albanian amalgam the founder of Association of Serbian Doctors, “father of Serbian surgery” and politician Dr. In 1913, Vladan Gjorgjevič published the book “Arnautët ed Fuqitë e Medha”, which aimed to question before the great powers the capabilities of Albanians and thus the right to have their own state.

This was a form of intellectual support for the six-month Serbian military operation in northern Albania in 1912/13, aimed at providing Serbia with an outlet to the sea, Gjorgjevic begins with the anthropological dissection: “The typical Arnaut is thin and small , there is something gypsy, Phoenician about him”. He then presents the aforementioned legend of prehistoric predatory humans. (pg. 7).

Since he introduced the Serbian factor into his story, Gjorgjevic was quick to describe the mutual influences in a black-and-white frame. Thus, the Albanians allegedly took the custom of brotherhood from the Serbs, “but they corrupted it, because while the Serbian brother considers his brother’s wife as his sister, the Arnaut can marry his brother’s wife who is still alive, and in Arnautluk people for a very small insult they kill each other…”! (pp. 9-10). Similarly, according to him, the armed uprisings of Albanians against the Turkish government did not break out for freedom-loving motives, but “only to avoid paying no taxes…and not to hand over the weapons they need so much to kill each other” (p. 41).

Gjorgjevic very diligently traces the prejudices about the insidious and capricious Arnaut. After the outbreak of the First Balkan War, 60,000 Albanians “with the rifles that were given by Serbia and Montenegro, crossed over to the side of the Turks and fought against both Serbian states, in their wild, insidious and treacherous way” (p. 41).

The Arnauts are presented as “bad shooters in frontal combat”, but very accurate in ambushes, which also alludes to their stealth (p.113). They “pretend to be dead, only to brutally kill some Serbian officer behind their backs.” Of course, then the officer catches all those traitors and tries them according to the law of war”! (p. 42).

The withdrawal of the Serbian army from the North of Albania in 1915 was not met with any sympathy from the local population, but there was also no organized resistance due to internal anarchy. In fact, at the same time there were six different armies in the Albanian territory. When the offensive of the Central Powers began in the fall of 1915, the organization of the Kachak groups intensified. (1)

—

1 – Vladan Jovanovic. Overview of the history of the Srbije/Yugoslavia relationship of Albania. (An overview of the history of relations between Serbia/Yugoslavia and Albania). Pesçanik.net, 7.11.2014.

With the help of paradoxes and dramaturgical twists, Gjorgjevic elaborates the image of “arnaut morality”! According to his version, the wounded Albanians did not stop their cruelty even in the Serbian hospitals, where one of them “with the teeth of a beast tore off a piece of the cheek of a merciful sister”. Gjorgjevic then points out: “And Austria-Hungary wants to make a state out of these beasts?” Good luck!” (page 43).

A very suitable topic for discrediting the Albanians was their customary right and blood feud, “which is not considered a crime, but a sacred duty”. At one point, Gjorgjevici says that over 70% of male deaths among Albanians come from blood feuds and that for them it was a shame to die in bed (p. 47).

Moreover, “in the Arnaut language there are no words for beloved and beloved”, he concludes pathetically (p. 115).

Writing about the savagery and anarchy of the Albanians, he mocks the bad farmers, who do not know how to make sheep’s cheese, who have not even heard of deep plowing and fertilization (p. 76). Gjorgjevic’s description of the armed Albanian, with mocking tones and failed stylistic figures, brings him to the brink of the absurd: although they have rifles, Albanians are completely untalented in hunting and fishing, and thanks to their innate backwardness they destroy beech forests pastures do it. (page 79).

To the remark of one of the travel writers, according to which in front of every Arnaut tower there is a horse’s head embedded in a wooden pillar, Gjorgjevic adds: “Thank God that there are no human heads on those pillars!” (p. 102). “Beautiful civilization!” shouts Gjorgjeviči, reminding the readers that Albanians, unlike Serbs, still eat with their fingers, that they are lice-ridden and do not change their clothes, and that “there is only one toilet in all of Arnautlluk” (p. 103 ).

The Russian consul in Prizren, Ivan Jastrebov, supported this aggressive stereotype with his impressions of the savagery of “liars” and “tricksters” Albanians, for whom theft was not a sin, but a “born vice” (p. 121). In his exaggerations and generalizations, the Russian consul loses his sense of proportion, but he does not worry when he writes that Albanians: “look like animals with human faces”, “they all go out naked”, “they are all notorious robbers and murderers” (p. 104 .-109).

With a strong sense of drama, Gjorgjevic leaves the issue of women for last. The Albanian woman is a “half-blood” without the right of inheritance, for whose murder the payment is twice as small as for the murder of a man. In addition, if she is barren, she leaves, while the man expects her to “carry wood, cook food, bake bread and sew dresses” (pp. 114-115). But Albanian women also have the other side, the bloodthirsty one: “these wild Arnauts always have to resort to blood feuds. This habit turns even tamed women into bloodsucking beasts, drinking human blood” (p. 107). Memorie.al

The next issue follows