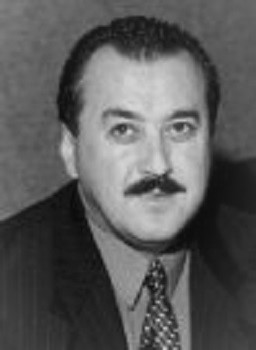

Dashnor Kaloçi

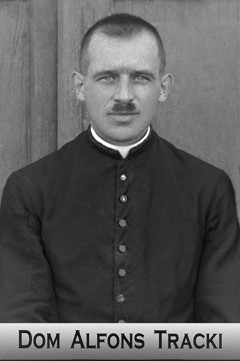

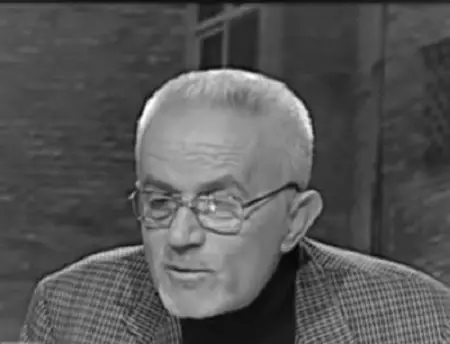

Memorie.al / On July 19, 1946, the “Bashkimi” newspaper of that time announced the decision of the Shkodra court, against 21 accused as: “War criminals and enemies of the people, participants in the Uprising of the Great Highlands”, where it was said that, Llesh Marashi, Don Alfons Tracki, Kolë Ashiku and Nikollë Preng Deda, were sentenced to death and by firing squad. Luigj Dushaj, the son of one of the convicts in this trial, testifies for Memorie.al, all that ordeal of torment and suffering that have accompanied him and his family, for years, during the period of the communist regime from 1945 until 1990. He does not even hesitate to mention the names of specific persons, as they tried to implicate him and include him in the trials against his friends, how he practiced painting illegally, through the centers and their sale in Tirana, until the fall of Stalin’s bust, in the middle of the city of Shkodra, in January 1990, together with Deda Kasnec, etc. After after that, in 1990, he emigrated abroad, to arrive r in Sweden, where he won political asylum, meanwhile he has opened the first exhibition with his works. For more, Luigj Dushaj, who came from Sweden, gets to know us in this interview.

Mr. Luigj, what was your father, Nikolle Preng Deda, up to the time he was arrested by the communists who had just come to power, and what was his connection with the other convicts of that trial?

Before the communists took power, for 3-4 years father was working as the mayor of Malësë i Madhe, based in Shkrel. Even today there are still many people alive who remember my father in that function and some of them have stopped me on the street and told me that; he called us and gathered us young people since 1938 and told us to be careful, that Albania could be endangered by Bolshevism. So, this shows that the father was against communism, since before the period of the occupation of Albania. Among other things, this was due to the fact that he had a lot of company with well-known intellectual people, such as Kolë Ashiku, and others, so they knew their business well. And starting from this, he participated in the organization of the anti-communist resistance, together with Prek Cal, Llesh Marashi and others, and in it, the first uprisings against that communist system, such as the Postriba Uprising, etc. Surely, the lack of organization and many other things led them to go to the mountain, since the communist regime in power had subdued the Great Highlands, a good part of it.

How old was your father at that time, i.e. in 1945, when the communists came to power, and did he have any influence in Malesia e Madhe, where he had once been mayor?

The father at that time was 36-37 years old and definitely had influence in many families of Malësi e Madhe. He had some friends; he had his own married sister there in Dragan, who kept him sheltered for 18 months, taking them out to eat and everything. I remember that it was said that he never accepted to have his food brought to him, unless they also brought him the newspaper.

Where did they find the newspaper?

They walked for several hours from Shkodra to Koplik, to deliver the newspaper to him. After 18 months and after many efforts and many sufferings. He was staying with Lek Mirukaj, a very good mountain family, with wonderful traditions. From time to time, the partisan forces at that time subjected him to various tortures and pressures, until a person from that house was strangled by beating him, his name was Gjon Lekë Mirukaj.

What happened after these pressures that were put on that family by the communist forces?

They went and said to my father: “Nikola, we do and will do everything for you all our lives. What do you think, should we take you somewhere across the border, run to Italy or somewhere else and get rid of this job”?

How did the father respond?

He told them: “I am absolutely not leaving Albania.” But I understand you very well, since the matter has come to this point, to kill you as a family, tell Bejto Fazli, said Nikola, that I surrender on one condition: Let’s go down to my sister, all together as we are, (because he has finished school with Beyto), let’s go eat and drink like brothers, but I don’t want you to tie me up to Shkodër”.

Did the communists accept the condition that your father imposed on them?

They have given him the word that we will not tie him, causing him to go calmly to the designated place, where father was sheltered. After that, they took my father and ate at my aunt’s house, then tied him up. At the time that they tied up the father, he pointed at them and said: “Bejto Fasllia, I have known them for a long time as unfaithful men; you promised me that I did not tie you up.” However, no one wanted to talk to anyone about his words and they finally took him, tied him up and brought him to Shkodra, where he stayed for several months in the interrogator barbarically torturing him. Then he was shot by court decision, with prosecutor Aranit Çela.

How old were you, do you remember these events of your father?

I remember that I was only 4 and a half years old, but I also remember when I entered the court barefoot, so much so that I am surprised even today how I entered and I remember it like now that he has been sentenced, together with Kola Ashiku, Llesh Marashin, Dom Alfons Trackin, Kel Abatin, etc. They were sentenced to a beautiful cinema that was then in Shkodër and that was burned down later. They tied them up and walked them to the “square”, (as we say in Shkodër to “Kafja e Madhe”), two by two they surrounded them with soldiers and policemen, taking them from the prison to the courtroom and vice versa. The next day, after the trial ended, (I remember it even today, that scene has never left my memory), it was July 17, 1946, when at 4:30 in the morning, we were sleeping outside, because they had also took the spoons of the house, laid with several layers because it was summer then, the automatic guns, the bullets of the rifles, somewhere behind the Catholic Cemetery in Shkodër.

Did you in your family understand why those rifles were at that time of the morning?

I was very young and I don’t remember very well, but I do remember that my mother and father’s mother stood up and shouted at the top of their lungs that they knew it was the guns that were killing those young men. I remember that time very well, when my father’s mother took me by the hand, that our house was not far from there, and she took me to the cemetery. There were those soldiers with rifles and my grandmother, crying loudly, wanted to enter her son, but they did not let her. She was a strong woman, I don’t even know how God gave her strength and she went inside and fell on top of her son, they grabbed her by the arm and pushing her with the barrels of the rifles, they also blinded her…! I will not forget this until I die. (Tears)

What happened to you and your family after your father was shot?

Ehhh, don’t ask, what did you sell me?! The persecution continued for almost 45 years, with me personally, with my mother, with my brothers, with my sister. Absolutely a huge spiritual, economic and all-round waste. Four orphans with nothing at home, absolutely no help, and no money, nothing at all. Because my father, even though he was mayor, was not a man who earned a lot of money, he was a simple man, an honest worker, an honest clerk, he built a small house in the “Skenderbeg” neighborhood ” in Shkodër and we lived for beauty, until my father was arrested. But even what we had was taken from us and our lives went away, like shaken and growing chicks, and for every year, the persecution increased because we were growing up and bearing this persecution on our backs.

What did you make a living with, where did your family members work?

The mother worked with a pickaxe in the nursery of the Forestry Enterprise on the outskirts of the city of Shkodra. Initially, Dr. Borja, (a very well-known doctor in Shkodër, who is known throughout Albania), brought him to work at the Civil Hospital in Shkodër, as a surgical nurse. They found out and a little later they fired her because she was so-and-so’s wife. They took him to the nursery of Pyjore with a pickaxe, there were three young girls who worked with them, they were wonderful girls and they were like our work to be persecuted and for that, they had put them in the pickaxe. They stayed close to their mother and she kept them close, as she advised them, that it is normal, they were young. He worked with a pickaxe and at that time, as far as I remember, they received 1,500 lek (old) in 15 days. But they also removed him from that nursery, because it was seen as a privilege, because it was close to the house, and they took him to Bushat. Nana has suffered a lot with four orphans and with my father’s 80-year-old mother, who pretended that she didn’t do any other work, only holding the photo of her son (my father, Nicholas) and saying: “How did you kill my son for nothing?” ?

Did you continue school…?

I finished the 7-year school, and then my uncle intervened with a friend and enrolled me in Pedagogy. I headed the Pedagogical school and teachers took me to Lezhë. I stayed 3-4 years in Lezha as a teacher and then in Trashan in Zadrima, there I met Father Filip Mazrreku, a wonderful man, I learned a lot from him. But for 3-4 years I lived there, because they took me as a soldier. They did not allow me to touch a handgun there, absolutely not only to me but also to others. I returned to Shkodër after my two years in the army ended and I started looking for a job, because we didn’t have enough to live on.

They didn’t take you to education, where were you before the army?

It wasn’t even about a teacher, absolutely not, because the class war started. This is how my life continued until I left in the 90s, when I was fired 5 times. When they found out that he is the son of so-and-so, (that someone told, or through anonymous letters), they fired me. It happened to me that among these 5 times, that I was fired, I did not sign the payroll for up to 6 years at all.

How did you live, how did you make ends meet?!

I have conviction that God is great. I have always been interested in painting, I continued painting, but I had no opportunity to practice it. I started crocheting (handwork like women and girls), I secretly opened a hole in the door of the yard and every time the door was knocked, neither I, nor my wife, nor my son, never opened the door, without looking before who it was, that there was a fear that I might be arrested.

Where did you sell those centers you made?

With great difficulty. I also came to Tirana by bicycle, I brought the centers, I worked on several sets (sailboats, etc.) for several weeks in a row, with the greatest secrecy, because we were afraid that it would cause me to be put in prison. So in secret I managed to sell doily, (ships, garlic), but it was very difficult, as I, as a person, found it very difficult to tell someone do you want to buy some of these?! Let alone that selling on the street was prohibited.

How did you manage to sell them?

There wasn’t a store in Tirana that I didn’t stop the bike and, for example, I took the doily and put it in a cardboard folder and turned the cardboard sheet a little, so that the doily (which was that worked flower) looked a bit , I said: Do you have coffee? “No, they didn’t tell us” where the coffee was found at that time. They saw the center and said to me: “Wow, what is this?” Center, I told them. “Where did you find it bro, can you see how beautiful they are”. I have managed to sell hundreds of doily, because God helped me.

Apart from these private jobs, have you ever tried to work in a government job?

I also worked in government jobs, as there were good people who helped me even then, even though my father was shot. I must never forget there was a doctor, Dr. Sandër Ashta, a neuro-psychiatrist (whom I grew up with), he is now dead and I will never forget him. The only person, the hospital director in Neuropsychiatry, has personally put me to work twice, without any interest. The last time, after 6 years that they left me without a job, they put me somewhere in rehabilitation in Psychiatry, in the Neuropsychiatric Hospital in Shkodër, where I worked for 5 years. I then worked in Fushë-Arrëz as a designer, etc.

When you worked in government work, were there moments that provoked you?

When I was working as a designer in Fushë-Arrëz, I remember that they put a tailor in prison, his name was Kolec Traboini. I was called to the Internal Branch of Puka, urgently. I was in Shkodër and they informed me and told me; to come urgently, because the Head of the Internal Branch in Puke wants you. To be honest, I was very afraid to say why they are looking for me, but surely I said that someone showed me (the biography work) and they are calling me.

Why did they call you?

For the work of Kolec, that tailor they had arrested. They have put me under tremendous pressure. They wanted to include me in that dance, to prove that; Koleci insulted the Party and Enver, every time we were together in Fushë-Arrëz. Until the end, I was pressured by various people and then at the end, they told me: “Okay, whose are you?” I told him so and so. “Why did your father die”, they told me? I don’t know, he was killed by the government and I don’t know anything more, I told them and they released me after they saw that they couldn’t break me.

Based on your biography and family circumstances, did you find it difficult to start a family?

It has been difficult without question. I created a family, married a woman, thank God, I am very happy with her. She was a teacher then, she was in the city, and just because she married me, they took her away and took her to the villages.

Where did you work in the last years before the fall of the communist regime in Albania and how do you remember the movements that took place in the city of Shkodra at that time, such as the first mass at the Rrmaj Cemetery, the demonstrations for the removal of Stalin’s bust, etc.?

In 1989, I was working in the Psychiatric Hospital of Shkodra, when that job slowly began to crack. I was in Tirana that day (with sale doily), that mass was held in Vorret e Rmajt by Dom Simon Jubani, I think it was Christmas night or the night before. That’s when I understood that that work is over, so that’s all there was to that regime. In my opinion, the biggest and first spark was in Shkodër, with the fall of Stalin’s bust, where I was one of the main ones, with Dede Kasnec, Flamur Elbasan, Rin Monajka, Gjergj Livadh and others (that he didn’t mention all of them), who were imprisoned and brutally tortured.

How do you remember that event?

Tracts were issued on January 13, 1990, the night before, tracts were issued from my house and Dede Kasneci came to collect them together with his nephew, Viktor Kasneci, if I’m not mistaken. I was active as much as I could, whatever happened, but in the 90s, that job was closed. Then he continued in Kavajë, the students in Tirana and so on.

When and how did you leave Slovenia?

In 1990, as soon as the first passports were issued, sometime from the beginning of the summer of that year, I couldn’t take it anymore and I sold the house in Shkodër for 1000 dollars and fled with my wife and children to Berlin, from Berlin to Sweden. The whole journey after some adventures, which were not easy at all, was the 90’s then and there were many problems, because immigrants from Eastern Europe continued to come to Western countries. We went by ferry to Trelemorje (it is the southernmost city of Sweden), and there we cried with great fear, since we did not have a visa, we had a visa until Germany. After we got off the ferry, I immediately went to the police and asked for political asylum. After I told them all the reasons that motivated me to go there, the Swedes helped me, fulfilling all the conditions, just as they lived.

And do you work as a painter there?

I worked about 60 works from old Shkodra. I was the happiest man in the world, when the exhibition opened in Sweden, it was not the problem of money, but the problem was that I felt that I had won, since my father was killed, but not the talent.

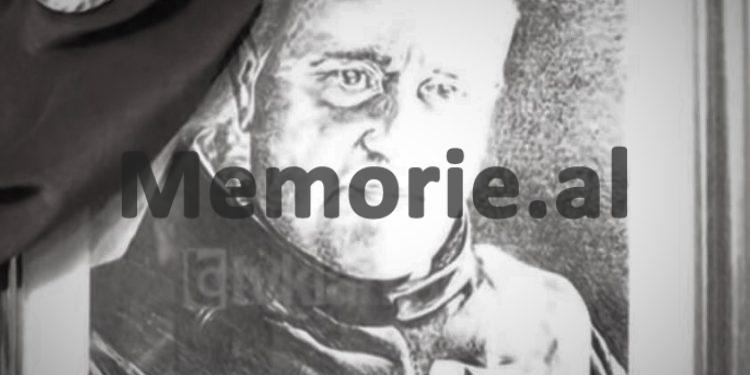

In the conversation we had before starting this interview, you told me that you own a medal that dates back to 1925, the “Medal of Merit”, donated by Pope Pio the 11th, Father Gjergj Fishta. How did it fall into your hands and why is this passion for this figure?

Since I was little, I was educated with the sayings and verses of these poets, by my mother, by my older sister, and so I continued until it seems as if I wrote Fishta myself with my own hand. I loved fishta and I love it so much that I opened an exhibition there with the Swedish albanologists, at the Franciscan building in Shkodër. A few years ago, I proposed to one of those Franciscans that we could do something for Fishta. “With all my heart”, he told me. There were as many materials as you want and something very beautiful came out. I remember in the “square” in Shkodër, I was with two invitations in hand and we wanted to give them to a friend. I called him, behind me was a young man, whom I had never seen, and he called me. Order it I said. “Can you give me an invitation too”, he told me? Yes, with all pleasure, I told him. Anyone who wants to can come.

You didn’t know him?

No, I didn’t know him at all and that’s why I said: but who are you, because I don’t know you? “I – he said – am so-and-so, surnamed Zojzi”, a very good family in Shkodër, grandfather after grandfather. He told me: “I want to give you this medal of Fishta, which was given to him by the Pope in 1925. Let’s meet today at 5 in the afternoon, so I can bring it.” When he said these words to me, my body trembled and I said to myself, how is it possible that the Fishta medal fell into my hand?!

How did you think about this medal, so rare and of great value, will you keep it or…?!

For me, it is important that this medal, when the time comes, be there where it deserves. Memorie.al