By Niazi Nelaj

The first part

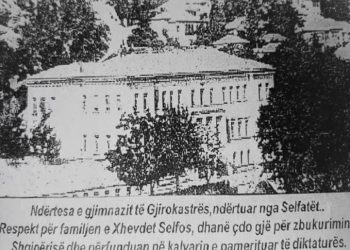

– At the Chinese Military Aviation School –

Memorie.al / Expelled from the Soviet School of Aviation, with dreams cut in half, part of the group of student pilots, who had studied for a year in the city of Bataysk, on January 8, 1962, after a “hell” cruise ”, with a cargo ship, we arrived at the center of China’s Third Military Aviation School in Chin Zhou City. It is located in the “Heart” of Manchuria; at that time there were about 200,000 inhabitants. Without any prominent industry. A city with 2-3 story buildings but paved roads. The terrain around the city was plain; next to it are the Western shores of the Yellow Sea. One of the values of this city was the fact that it was the center of China’s Third Military Aviation School. My going to this school and that city was a lucky chance. In the list of 7 students of our course, which included: Adem Çeça, Dhori Zhezha, Mihal Pano, Bashkim Agolli, Andrea Toli and Sherif Hajnaj (Bracki), my name, Niazi Nelaj, was included, quite by chance?

To me and my friends, from the subgroup, a light of hope was opened for the continuation of the flight program, where we had stopped it. At the same time, the selection of Manchuria, as a place of deployment, was a wise finding by our side and the host side, dictated by the conditions that were created after the termination of our country’s official relations with the Soviet Union.

Manchuria was not chosen by chance as the place where we would be educated in the field of military aviation. The geographical position and the harsh climate, without precipitation, similar to that of the North Caucasus, many sunny days and good horizontal visibility, allowed year-round flights. The terrain and weather conditions were suitable for the air training of foreign students. Manchuria is near “safe” countries such as: Mongolia, the Soviet Union, North Korea and the Yellow Sea. Any evasion of the case, by the pilots, which could have brought the plane close to the state border with these countries, did not constitute any serious danger for interstate relations at that time.

We had trained and lived in the conditions of Russia, in its vast spaces, where the winter is long and harsh and the summer is dry and short. Approximately, we found a similar climate in Chinese Manchuria. In Liao Ning province, where our city, the new settlement, was located, we found a continental climate, with temperatures down to -25 degrees Celsius, with cold and strong winds, without snowfall. Familiar with the Russian cold, it was judged that we would more easily cope with the low temperatures, which are characteristic of this Chinese region. There were also social and historical reasons which were on our side. Historically speaking, Manchuria, inserted as a safe “pocket” between several countries in the region and prosperous, has been under Japanese occupation for a long time.

For the sake of truth, the Japanese invaders had not only brought destruction and plunder to those lands, but also development and civilization. At other times, Russian and other nationalities had passed through Manchuria and fought or settled. However, the natives had also benefited from the floods in different ways. Thus, Manchuria, like the great ports of that country: Shanghai, Canton, Hong Kong, Port-Arthur, Can Gyan, etc., was one of the most developed regions and the people had the most elevated cultural level, in all Chinese spaces. . The city of Chin Zhou was indeed small, but the people were physically more developed and had higher development indicators. In Manchuria you could find people in every corner who spoke Russian.

The population of the Manchuria region, therefore also of Liao Ning province, where our city was located, belong to the Confucian religion and if we can say to one of the oldest and greatest dynasties of the Chinese Empire, that of the Han. There were many pagodas in the whole terrain; a sign of the rooting of Buddhism in the people.

As for the conditions for flying, in Manchuria they were like in all of China, but there were some facilities, which were in our favor. One eye was the lack of high mountains. The coastline, with all its bends, made it easier for us to visually orient ourselves from the air. From North-West to South-East, meandered several rivers, which, although not full of water, were clearly distinguishable, as characteristic landmarks, for pilots flying at medium altitudes, such as our work.

In that flat terrain, where the hills have to be “searched” with your eyes, the “small” rivers: Ta Ling Hë, Xiao Ling Hë, Hei Sui Hë, Vampa Hë, etc., seemed to scratch the land, taking alluvium with them and taking momentum, to pour into the Yellow Sea. The dense network of concrete airfields in the North-Eastern lowlands of China and the great distance of our deployment site from the “hot spots”, such as South Korea, Taiwan, Tibet, etc., were also in our favor. Perhaps, in defining Manchuria as our training and living region, the fact that the region was prosperous and markets for providing food were closer also influenced.

For the theoretical preparation and airplane training, the owners of the house had selected the best specialists, who were distinguished for outstanding theoretical-practical and pedagogical level. Since we came from a country known for high scientific levels of pedagogues and as instructors we had pilots with rare piloting techniques, the organizers of the Chinese aviation school took care to have the highest levels of their specialists work with us. They had given tests by training their pilots and made sure that there was no drop in levels.

Love for the country prevailed over the difficulties

The Chinese are well-known in the field of reception and hospitality. Upon arriving at the Aviation School on January 8, 1962, the locals treated us to a fantastic welcome ceremony. We had never seen such a reception in our lives. Without further ado, below I will try to recall the way of organizing that presentation, which resembles the well-organized rallies of some political parties, nowadays. As they say in our country: “they were uprooted, with a knife and a machete”. Locals, military and civilians, lined up on both sides of the road leading to the school.

Many hosts were holding Chinese musical instruments. Characteristic gongs and some instruments of large sizes, strange in appearance and in the sounds they produced, dominated. When they rubbed against each other, they emitted a metallic sound that “pierced” into the brain. Others played other instruments, which we had not seen before. It didn’t matter the harmony of the sounds and the melody, it was enough to make noise. Among those who had come out to meet us, the young age dominated (I mean about 30 years old). Everyone was laughing, or it seemed to us that they were laughing, because their teeth were visible, more than the rest of us.

What shocked me was the uniform worn by those who welcomed us. We had seen and worn the uniforms of the Soviet, Albanian and other “friendly” soldiers and we were used to seeing soldiers who loved their uniforms and made sure they were as handsome as possible. Those who received us were dressed as they could and their uniforms looked like a mosaic, with strange colors and shapes! There I saw, for the first time, a “hybrid” uniform; half of the military was dressed in military uniform; the other half – in civilian clothes. I will try to be more specific in describing this.

In general, both military and civilian, their clothing was made of cotton. Khaki color dominated. Among the hosts, there were men, but also many women. In general, people, regardless of sex, were dressed in trousers and jackets. Soldiers wore hats with brims or hoods; civilians – as desired. Since it was cold, everyone had their heads covered, with something. Even we, who came from hot countries and had left Albania, at the end of November last year, with light clothes, in Beijing they provided us with some long coats, dark in color and we looked like dormitories.

Our coats were long, waist-length (about 25 cm. from the ground), warm, and made of a quality piece of cloth. They saved us from the cold of those bitter days. The clothing of military women caught my attention. None of them were pilots. They were wearing some sweatshirts, khakis, with a doku cover, knitted with a cotton layer inside, like those “fur coats” that our mothers used to knit by hand. Their sweaters were waist-length and kept them tucked in.

Their breasts were not visible from the outside and, at first sight, a novice, as we were in that country, found it difficult to know whether it was a man or a woman. I say this, based on the fact that military women kept their hair cut short, enough to cover the neck and, below the waist, wore pants; like men. If you observed them carefully (we gained the experience day by day by being among them), you could distinguish the man from the woman, just by the face. Women, in general, have a pale round face and do not paint their lips.

The pilots were wearing flight uniforms. In the set of their uniform, there was a sweatshirt, short, up to the waist, with a chain, and with a wide elastic at the end; with a large plush collar and breeches, which were tucked into ¾ boots. The sweater and kilt pants were made of leather; soft, warm and resistant to burning. The brief surprised me. The pilots wore ¾ leather boots, which went with the outfit. Some soldiers wore leather shoes, with necks, with thick rubber soles. There I saw some soldiers, who were wearing a kind of cloth shoes; black, velvet type on top and white, knitted and hard on the bottom. This type of clothing was favored by the climate of the region where rainfall was very rare and humidity in the environment was absent.

To shoes of this type, which were quite close to our slippers, the locals called them: “Puse”. I emphasize that these types of shoes were quite light and strong. They supplied us with such shoes, and later also us. There were also soldiers and civilians who had come to meet us, wearing lepitka (slippers). What surprised me was a kind of cape that some soldiers wore. They were woven from a kind of juke (hard, flexible grass), tied at the top and let loose at the bottom.

They resembled the shack that shepherds carry to keep them from getting wet, on our side, but the man who had thrown that swag gave the impression of a miller with hay. Interesting was the fact that such a cape did not let water in and was strong. I compared these types of capes to the fur of our shepherds, but they were made of grass, while the fur is made of wool from sheep, which must be selected from the best wool of the flock.

In addition to the low temperatures, from time to time, in the city we went to, as in the entire region, a cold wind blew, which “dried” your face and hands, if you had them exposed. To protect the lips from cracking, the Chinese put on their faces, white, nappa masks, like those worn by our sanitary workers or those who serve in commercial food establishments. The masks had laces, which were used to keep them closed, behind the face, in order to protect the skin. Such masks, then we also decided. They were indispensable, especially when we were forced to circulate in environments outside buildings.

That day, our hosts had come out, almost all equipped with this protective gear, and it was quite difficult to distinguish people from each other. Liao Ning Province, where we went, is near Inner Mongolia. To its West, is the Gobi Desert? The wind coming from the North-West brings with it fine sand particles, which gives the air a reddish color, visible to a sharp eye. The masks also served to protect the respiratory organs from this annoying and harmful dust.

In the row I also noticed some female soldiers, with long braided hair, with two branches, which hung down to their hips. Even the presence of long, braided hair was one of the distinguishing signs to understand that you had a girl in front of you; single. Married women, as a rule, kept their hair short. Without departing from the way of haircut, men preferred the ‘polubox’ haircut, according to the sailor’s haircut. Hair should not stick out of the hats. I emphasize that, in the report of women’s likability, based on the length of their hair, the most preferred were those with long, braided hair. The Chinese were dominated by straight, rough, wire-like hair of black color. The gray eye was rarely seen. I’m not just talking about the people who lived in the military town.

When we saw that crowd of people, in its strange diversity, I got the feeling that the organizers of the “spectacle” had mobilized whoever they found on the road and brought them there to honor us. Today, after almost 60 years, when you see how, against the lists, school students and their teachers, or administration employees are mobilized under the threat of losing their jobs, to participate in electoral rallies, against their will. it occurs to me to draw a historical parallel between the events of that time, in distant Manchuria, with today’s developments in our country.

I can say that Chineseness is not only in China. But Chineseness neither starts nor ends here. In that interesting reception, but not only there, I was impressed by something, which I had not seen, neither in my country, nor in Russia. Everyone who welcomed us was laughing. They had large, white teeth that protruded from their lips.

Almost everyone was happy and happy with our departure. At first we didn’t understand the connection between a Chinese man’s fake smiles, with his eyes moving from left to right without saying anything. Later we learned and understood the meaning of this typical expression “Chineseness”. Now it occurs to me that at that time and at that age I did not want to know that the “demonstrators” were ordered to behave in that way.

What surprised me even more was the absence of flowers in that grand ceremony. I didn’t notice anyone holding flowers in their hands. The organizers had taken care, in detail, to create the most comfortable, warm and friendly but also illusory environment for us. We came from friendly Albania and were student pilots, expelled from the Soviet Aviation School.

Both qualities we had could not be appreciated and respected. Each participant held a musical, wind instrument or one of those characteristic gongs that only made metallic noise, which soon became unbearable for us. The noise pollution caused by those original musical instruments was unprecedented. The absence of flowers in that grand ceremony was perhaps a matter of ritual or conflicted with the rules of military life. I never understood that!

The festive ceremony lasted 10-15 minutes. We marched, with a free step, but with our heads held high, like “heroes”, between two rows of locals, accompanied by the enthusiastic cheers of the hosts. Perhaps in that city, people saw for the first time, so close, people who came from Europe; people whose skin color was white and whose nose was big. If we add here that we came from a “revisionist” country, as it was considered, at that time – the Soviet Union, to a “Marxist-Leninist” country such as China.

The cheers echoed the pure and unbreakable friendship between our two countries and our two peoples; they wished long life, very long, (10,000 years of life) or, as they articulated in their language (Van Sui), Chairman Mao Zedong, the leader of China and the whole world. They shouted in Chinese and for the leader of our party and people – Enver Hoxha. A group of Chinese, in the choir, sang a song which, at that time, was very popular, especially in military environments. The lyrics of that song, as far as I remember, were like this:

“Hey son,

Let’s believe,

Kuçanto makes his pocket,

Here it is, the next day,

Hello son,

Hey, where’s the Yenmin…!

Others sang a more moderate song, with musicality and a patriotic accent. As far as I remember, after so many years, the lyrics of the song were like this:

“I swear to Tjengjin, I swear to Tjengjin,

You have my heart,

Whoa, ni jao tan sh…!

We entered the grounds of the Aviation School. All that tumult of people, noisy and as if “grown”, on the asphalt, as if by magic, was bandaged. The noise stopped and the people dispersed, going about their business. For us 20-year-olds, who were coming from a long cruise and a train journey, in lower class carriages, from those of the first journey; from the South of the country, from Canton, to Beijing, the ordeal of waiting and annoying ceremonies, there was no one.

The High Hierarch of the Third School of Chinese Aviation and those of the city garrison led us in a “dignified” presentation of the environments where we would learn; in the rooms where we would sleep and in the food block. We saw the classrooms, the canteen, the dormitory and the laboratories. In every place we went, we found happy people, who were laughing for some reason, and we encountered Asian-type warmth, with pronounced Chinese nuances.

In the surroundings where we were going to sleep, we found what was beyond our wildest imagination, which we would never want. Even I, the peasant, who grew up in the village, in very difficult conditions, without even the slightest comfort, was impressed by that way of life. Some senior officers of the school among them and its commander himself made us company and introduced us to the living conditions. We were in a living room, which served as an anteroom to the living room. Seven Albanian students, for pilots and 5-6 senior Chinese officers. Memorie.al

The next issue follows