From Amik Kasaruho

Second part

Memorie.al / Amik Kasaruho were born in Tirana in 1932. His father, Qemal Kasaruho, was shot by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, after the bomb incident in the Soviet embassy in Tirana, in 1951. At the same time, when he was only 17 years old and a student at the high school in Tirana, Amiku was arrested and sentenced to 10 years in political prison, accused of agitation and propaganda, and by court decision, he was expelled from all schools in the country. After his release from prison, in the period 1956-1962, he lived in the city of Kavaja and then was interned with his family in the village of Gose i Kavaja, (where their family stayed until 1990, when the communist regime was collapsing). From 1956 to 1960, Amiku worked as a manual laborer in Elbasan, Lushnjë, Kavajë, then as a construction worker in Gosa, surveyor and as a construction technician in the State Construction Enterprise in Durrës. Meanwhile, during the 60s, he was also involved in translations, but his name was not included in the books and texts he translated. Only after the fall of the communist regime in the early 90s, it became possible to publish his writings and books. At the beginning of the 90s, he left Albania and after living for a long time in Italy (where he wrote several books), in 2009 he returned to Tirana, where for some time, he also served as an advisor to the President of the Republic. Also at this time, he also dealt with essays and translations. His books, such as “Anxiety of half a century”, (1997) “The price of a dream”, published in Italy (2000), “Between the sky and the prison”, “Escape from the fantasy of the gods” (Autobiographical novel), “Without grudges – Journalism of my life ” (2013), (which includes writings and interviews of the author, published in the Albanian press), have been translated into foreign languages and some have been honored with international awards. Likewise, Amik Kasoruho has also translated into Albanian works by foreign authors, such as: Pirandello, Isabel Allende, Harold Robbins, Patrick O’Brian, John Selby, etc. One of his last translations was “Atlas Revolt” by the well-known American writer and philosopher Ayn Rand. Kasaruho is the winner of the special jury prize in the Eks & Tra contest for immigrant women writers in 1999. In 2000, she received the “Civitas – Arberia 2000 Calabria” award for the maintenance of the Italian-Albanian arborist magazine “Katundi Ynë”. Kasoruho has been decorated by the President of the Republic with the title “Honour of the Nation”. He passed away on May 5, 2014, at the age of 82. The writing that we have selected here for publication is taken from his book “Anxiety of half a century”.

Continues from last issue

FRAGMENTS FROM THE ESSAY BOOK “A HALF-CENTURY ANXIETY”

The birth of a party or “Mortis Tua Vita Mea”!

Hundreds of houses were burned or razed to the ground. Thousands of people were shot in the provinces of Dibra and Mirdita, in Dukagjin, in Krujë, Mat, in Malësi i Madhe and in Central Albania. Just as many were exiled or imprisoned.

Small villages like Gradishta, Grabjani, Plugu, Llakatundi became synonymous with civilian death; whoever was sent there, except in very rare cases, never again had the opportunity to leave the sight. Tens and hundreds of families remained in these camps for more than 40 years: where the convicted people were interned, after half a century their grandchildren grew up. A continuation too tragic to believe!

Bedeni (in 1947), Maliqi (in 1948), Vlashuku (in the fifties), Spaçi (recently) and other places were Dachau, Mathausen, and Buchenwald of Socialist Albania. Those who managed to escape from these “work camps” called themselves lucky people.

The internal pressure, which was exerted in all directions, the persecutions against the opponents, the malicious attitude towards the simple people of religion and especially towards those of the Catholic Clergy, the limited and politically channeled artistic expressions, the censorship even of the thoughts, the fear: on these tracks the new state was moving.

Even in foreign policy, things were not going well. The West did not listen to recognize the government that was formed during the War. For such things, there have never been a lack of cases and diplomatic skirmishes, but the main reason why such a thing happened was Albania’s lack of credibility in international relations. As if the discrediting done to the allies during the war was not enough, immediately after the liberation, the arrests of Anglo-American “agents” began!

Allied military missions and even UNRRA were accused of having turned into nurseries of agents. Let’s add one more example to what was said in the previous chapter: Reshad Asllani, arrested in 1951 on charges of agitation and propaganda, was also accused of being an agent of the Americans when, in fact, he was only deputy director of the Agricultural School of Kavaja.

The last trigger was the Corfu incident. In the strait between Saranda and Corfu in Albanian territorial waters, English ships encountered several mines that caused casualties. The Albanian government responded to London’s protests, which disputed Albania’s failure to signal the danger, saying that the mines were placed by German troops during the war and that the British protests were intended to incite the “cold war”. This hard line continued even after the Hague Court condemned Albania to pay damages from this incident. This decision was not accepted and the British confiscated the gold of the National Bank of Tirana that they had found in Germany at the end of the war.

All this gave way to the propaganda that presented Albania at the center of Anglo-American imperialist goals and justified the countermeasures taken by Hoxha’s government, including the closing of the American and English diplomatic missions in Tirana.

The answer was not delayed: Albania was the only country that was not invited to the San Francisco Conference. An emblematic historical parallelism would be verified in 1990, when Albania would be the only European country that was not invited to participate in the Paris Conference. It was a vicious circle within which a people writhed in search of lost freedom.

Satisfied with empty spoons

And within a vicious circle, the economy also writhed.

In the fields, in 1945, nobody had harvested anything: a part of the land had remained uncultivated; a part of the products had been damaged by the war. But, even though it may seem strange, immediately after the end of the war, Albania had fewer problems of nozzles in goods of wide use than the neighboring countries. This was either because the conflict had not been as fierce as elsewhere (in Greece, for example), or because during the five years of fascist rule, a relative well-being had been observed. Wanting to treat a proud people better, Mussolini provided Albania with all that Italy lacked.

While in Italy many items were rationed, rationing was introduced in Albania only after liberation (and it would last more than fourteen years, proof of the weak state of the Albanian economy, at a time when the Marshall Plan was operating in the rest of Europe).

During the years of the fascist occupation, the trade recognized a development like never before; the village had produced not only for the needs of domestic consumption, but also to export to Italy, causing Italian gold to accumulate on this side of the Adriatic. Fertilized Kosovo had contributed with abundant harvests. Trade with the Greek and Yugoslav border areas was entirely in favor of the Albanians, due to the devaluation of the drachma and the dinar, also provoked by the German brand of occupation. In Albania, also due to the persistence of the government headed by Ibrahim Bicaku and especially as a result of the work of his Minister of Finance, Et’hem Cara (both of whom graduated in Germany), and those inflationary phenomena that devastated the economies of other neighboring countries.

In short, everything suggested that there were reserves in the Albanian territory that could meet the country’s needs for several years. But in 1945, the consensus came out differently, giving proof of how a country should not be administered. Albania, even though it had several oil-bearing layers, remained without electricity for almost three years after the war: in the big cities, the lights were turned off at 10 p.m. It was decided to freeze all food and manufacturing products. On the black market, a kilo of sugar cost as much as three days’ wages for a specialized worker.

Meat was even more expensive, when it could be found. Whoever lost the triska, did not have the right to receive another for the same period. Everyone’s life was so obsessed by the triska system that, at that time, there was a saying: “How are you doing, how are you? Do you have Triska with you? This is how the owner of the house addressed a casual friend, to whom he had no opportunity to put anything in front of him.

None of the government officials said even half a word about the causes that had led to such a problematic situation. Later, when the relations with Yugoslavia were cut, it started to be said that it was the Yugoslav policy that had absorbed all of Albania’s resources. And this was said by those who, with the government of Belgrade, had signed a pact of friendship and mutual assistance, a two-year trade agreement, a customs agreement and a monetary agreement: and all this was done at a time when the Yugoslav economic conditions were well known.

This policy, to give almost everything without receiving anything, not to consider the needs of the people even when it comes to vital needs, slowly led to the creation of an absurd and self-destructive mindset that, after a few years, would force Albania to trade with different countries of the world, causing the denigrating impoverishment of its own people. In July 1991, on the occasion of the visit of the American Secretary of State, James Baker to Tirana, a banner read: “Give us our daily bread today”! After 45 years since the war ended, there was no bread in Albania! Well, at the beginning of the eighties (or at the end of the seventies?) a South American institute, which was removed as an arbiter of the standard of living of different nations, gave Albania the first prize! There was no way to invent a more cruel irony, a more mocking insult and a more humiliating lie!

In return, the Yugoslav “brothers” helped to build the country’s first railway, made with out-of-use materials, some of which, as a production date, bore that of 1910! The earthworks and the construction of the route or the concreting of the bridges were carried out by the Albanian youth, with voluntary work. Barefoot, naked, with picks and shovels, those enthusiastic young people signed with blood and sweat this “great gift to the Albanian people from Marshall Tito’s Yugoslavia”.

The big words, the evaluations that didn’t cost a second, the praises without stability, and the endless slogans were the reward for what he worked and produced.

The broom and the axe

The policy aimed at leveling rewards and encouraging sloppiness was also directed at artists. Enver Hoxha was well aware of Fishta’s genius, Konica’s sharp insight and deep culture, as well as many other intellectuals, but the country had to focus its attention only on him. But Hoxha’s egocentrism is only a partial explanation; Fishta in his poem “Lahuta e Malësësi” had proclaimed the autochthonous character of the Albanian population in the lands of ancient Illyria and had shown that the source of all subsequent misfortunes of Albania had been Serbian nationalism. Discrimination against Fishta is also related to the Serbian political factor.

The good relations with the federation of Yugoslav states imposed guarantees from the Albanian side. Condemning Fishta’s work and erasing him from the nation’s memory, accusing him of being a fascist (his appointment as a member of the Italian Academy in 1940 served as a trigger), was one of the many favors he so devotedly offered to the Yugoslavs Enver Hoxha. If for the Yugoslavs this attitude was a small concession for the package of concessions claimed by them, for the history of the Albanian culture, it was a dishonorable and shameful tribute. No one could mention Fishta anymore and Hoxha breathed freely: once again he had earned the sympathy of the Slavs. In the fifties, the writer Mark Ndoja was expelled from the Writers’ Union and later imprisoned, because he had proposed the rehabilitation of the great poet.

But Fishta was not only a talented writer, outstanding linguist, sharp journalist and a valuable public social figure: first of all he was a priest and moreover a priest of the Catholic Church. In his person, the entire Catholic Clergy, who had played such a big role in the formation of Albanian culture, was attacked. Dozens of church people’s names were erased from Albania’s history with a sweeping past. This was another step towards shame.

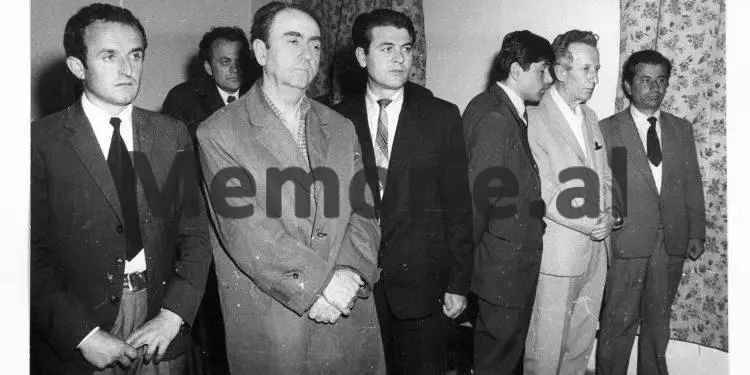

Intellectuals, who were preparing to found an opposition party, the Social Democratic Party, were also tried and sentenced. Those who were not shot were sent to prisons for many years. Among them were Gjergj Kokoshi (Minister of Education immediately after liberation), Suad Asllani (lawyer), Sami Qeribashi (intellectual), Musine Kokalari (writer) and many others. Their trial remained an example of the supremacy of those who, having firmly rooted principles, do not recognize the supremacy of brute force.

Later, it was the turn of the so-called “Malik group”, a group of engineers and technicians, accused of sabotaging the works of draining the Maliq swamp, works that progressed slowly only thanks to the organizational incompetence of the state.

All over the country, files from military courts were browsed to “prove” the guilt of the defendants. Engineers Kujtim Beqiraj, Sulo Klosi and Andrea Xega, lawyers Baltazar Benusi, Haki Karapici, Asllan Ypi, clerics Donat Kurti, Vinçens Prennushi and Pjetër Meshkalla, doctors Irfan fell to the blows of socialist justice. Pustina, Aqif Hysenbegasi and Ahmet Sadedini, professors Anton Deda, Foto Bala and Ali Cungu, poets and writers Arshi Pipa, Kudret Kokoshi, Pjetër Gjini, Mustafa Greblleshi and Dhimitër Pasko, economists Pjerin Guraziu, Skënder Cikla and Qemal Kasaruho, to mention only some of that endless line of names that, saved from a guilty oblivion, would constitute the pride of a free and grateful Albania towards its sons who suffered for a better future. God’s ways are endless: the history of Albania and the turn that has started these last month’s prove this.

Sword of Damocles

All the manifestations of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (read anti-cultural) were imported to Albania for the deep satisfaction of the one who discovers that he has a collective drug in his hands. Macbeth had killed his own sleep. Enver Hoxha would kill the sleep of others. In the early 70s, he directed his anger against the XI Radio-Television Song Festival. On the pretext that a path had been left for the bourgeoisization of socialist realism music, he dismissed, expelled from the party and arrested two members of the Central Committee, Fadil Paçram and Todi Lubonjë.

After them, climbing higher in the hierarchy of the propaganda apparatus was Ramiz Alia, who headed the ideological sector of the party. He escaped by a hair, it was said, thanks to the intervention of Hoxha’s wife, Nexhmija. If this is a good thing for the Albanian people, it will be possible to say only in the future. The fact is that, later, during our days, Ramiz Alia would be at the head of the party when the demonstrations in the city squares would be verified and the student movement for democracy would begin.

The economy was not catching up. In order not to admit that this was related to the harmful effects of the regime, even in this case it was found who should go for dog fat. He met Abdyl Këllez, member of the Political Bureau, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance; Koço Theodhosit, member of the Central Committee and Minister of Mining Industry and many other leaders of economic institutions. Even the Army was no longer a guarantee for the ruling class.

There were many, almost too many, those officers who had studied in the military schools and academies of the USSR. Therefore, in the ranks of the army, the ax of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat fell, and Beqir Balluku, member of the Political Bureau, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defense, General Petrit Dume, member of the Central Committee, Deputy Minister of Defense, General Hito Çako, were executed director of the Political Directorate of the Army, as well as dozens of other generals and officers were arrested.

These drastic measures were presented as a response of the Party to the conspiracy organized by the enemies of socialism in the field of culture, economy and the army.

For some time, Enver Hoxha would not feel the instinct of revenge.

In all spheres and sectors of political and social life, excluding members of the Political Bureau, the leveling of values went further. Everyone had to do manual labor for a wage that no longer burdened the state but was, in theory, tied to productive capacity. This, they said, was done in order not to lose ties with the working class. Calluses, whether in the hands of a minister or a violinist, would serve the cause of socialism. It did not matter that this month turned into a period of supplementary holidays at the expense of enterprises and agricultural cooperatives, which paid for work that was not done.

In 1966, the Democratic Front (actually the Central Committee of the ALP) addressed a call to state cadres to leave the city “voluntarily” and go to the villages, where they would contribute to their development. After the initial voluntary period (of course everyone raised their hand in approval), it was the party that determined who had to leave the city and, in many cases, with their families. This was another way to remove from places with responsibility all those who had a tendency to think more than what was allowed.

The fight against bureaucratic, this disease of Albania, recognized several phases. But always after each wave of “reforms”, the administrative apparatus grew even more. These purges, even though they sometimes had no political character (even though the first to leave would be those who had some “blemish on their biography”), were meant to make the state administration more flexible. But this was inflated again, in the name of a wider distribution of responsibilities. It was therefore not the result of the will to heal a sick organism: the real purpose of these “reforms” was to keep uncertainty alive. Staff turnover could affect anyone. The sword of Damocles had found a place in Hoxha’s arsenal. The party, officially, was concerned and did its job to avoid the bourgeoisification of civil servants.

Cultural impoverishment

A rich spiritual letter can encourage the desire to make changes. Indoctrination, therefore, should not exclude anything: not even the songs of light music. Albanians should have danced listening to the praises of the Party and Hoxha; accompanied by the melody of a foxtrot, they would learn how much the friendship between the peasants and the working class had strengthened as a result of the marriage of a distinguished milkmaid to a tractor driver. The notes of the waltz were accompanied by praises directed at Tirana, which would become more and more beautiful with its new mechanical offices and neon lights. To weave these texts, all the poets of the regime were put into competition.

The hardest blow to the arts was given by the decisions of the IV Plenum of the Central Committee in 1973. Writers were forgotten or arrested: Mehmet Muftiu, Petro Marko, Mark Ndoja, Ibrahim Uruçi, Bilal Xhaferri, Minush Jero, Kapllan Resuli, Kasëm Trebeshina, directors Mihallaq Luarasi, Kujtim Spahivogli, architect and painter Maks Velo, painter Edison Gjergo, bass Lukë Kaçaj, actors Edi Luarasi, Justina Alia, singers Sherif Merdani, Besnik Taraneshi, critic Vasil Melo and many others.

Even Ismail Kadare, the most important writer formed in the school of socialist realism, became a victim of the system that had supported him, proving the tightening of the walrus of that literary school. He had to modify the book ‘Dimri i madh’, to highlight the figure of Enver Hoxha, even managing to change the title of the work, which in the first edition was called ‘Winter of great loneliness’, to reference to the situation created after the breakup with the Soviet Union.

The translations by Latin authors, made by Guljelm Deda and Mark Dema, were never published, just like Pirandello’s novel for a year, Trilusa’s poems or Blasko Ibanez’s novels, translated by the author of these series. Pashko Gjeçi had to wait years to see “Divine Comedy” published in Albanian. From the classicist Henrik Lacaj’s translations, not much was published. Vasil Gjymshana, interrupted the work he had started, because the censorship crippled the writings of Voltaire that he was translating.

Robert Shvarc, one of the best translators of the last 35 years, was threatened in the district Party Committee with prosecution if he did not immediately withdraw from circulation the typewritten manuscript of his translation, ‘The Arch of Triumph’ of Remark. Apart from the poets and writers of the past, the poet Lasgush Poradeci, perhaps the sweetest and most refined poet of all times, was condemned to oblivion; the witty and original novelist Mitrush Kuteli; Arshi Pipa, poet of the last generation, critic who penetrated the essence of phenomena with vigor and honesty; Branko Merxhani; valuable and courageous journalist of the 30s.

Magazines that had made a fundamental contribution to the cultural, linguistic and philosophical life were indexed: Leka, Hylli i Drita, Illyria, Njeju, Fryma, Albanian Effort, Albania, Kritika, Demokracia, Bleta. Almost all the books that had contributed to the development of the country were withdrawn from the public libraries. Memorie.al