From Liri Lubonja

Second part

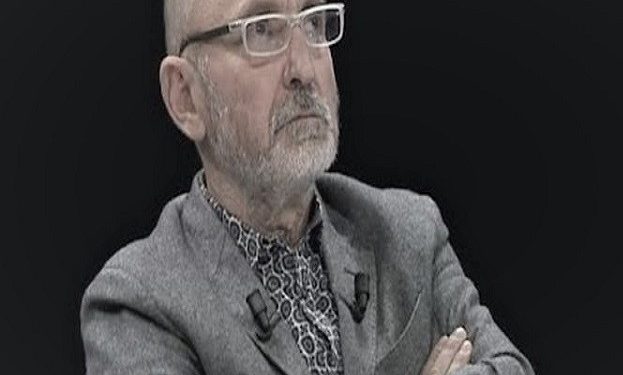

Memorie.al / Liri Lubonja, is the wife of the former political prisoner, Todi Lubonja, former Director of the Albanian Radio-Television, beaten “for liberalism” by Enver Hoxha in 1973-74 (after the 11th Festival National Song in RTSH), ending up in Burrel prison from 1974 to 1987 and also she is the mother of the well-known writer, publicist and journalist Fatos Lubonja, also a political prisoner, from 1974 to in 1991. Liri Lubonja has skilfully narrated in the book “Far from the people”, the vicissitudes, sufferings and persecution of her and the entire Lubonja family, during the years of exile. A woman who testifies to the suffering of women in the socialist system, for which she herself had fought.

Continues from last issue

FRAGMENTS FROM THE BOOK “FAR AND AMONG PEOPLE”

(Memories of exile 1973-1990)

Punished

In the 60s, I had read a book in Tirana, in Italian, “La morte civile”. “Citizen death” the author had called that phenomenon, which happened in socialist countries with cadres of the party or the state, who suffered and were punished by the party, described such a “death” of a woman in Romania.

Since then it had made a very deep impression on me, I had almost experienced that event as my own, maybe even because she was a woman. Such “deaths” had happened to us as well, but, with the exception of some acquaintances, which had hurt us, the others we had lived palely.

Why had this happened? Now I was often asking myself this question and it seemed to contain a sense of guilt and reproach. Was it some well-being and daily work that made us not deal with others? When the Deportation-Internship Commission was created, whose existence we learned only in 1974?!

From time to time we casually heard that the interned X or Y was working here or there, but it was added that his children were studying in schools and that they lived without responsibilities and without problems. On the surface this was a mild, even acceptable blow. But you haven’t really been like that.

That “death” of a living person was really absurd, ugly, and unacceptable. How did your relative turn into a stranger, never known? Here, he passed me on the sidewalk of the main street. Who knows why he had come to Lezha. When he approached, he not only did not look at me, but turned his head to the other side. You didn’t even have time to be surprised. Up to here?! As in fairy tales or fantastic stories, you had suddenly turned into an invisible being for those who did not want or were afraid to look at you.

The first people who didn’t recognize me were the office people, the intellectuals. I started not to recognize them either. How they looked to me, how miserable, writhing and suffering when they looked at me on the street from afar. I had no reason to wonder. Hadn’t I heard that refrain at the gate of the investigation: “Thank you is not for politics”. A woman convicted of theft, served her prison term and returned to our neighborhood.

With what kindness and cordiality all the neighbors met her, at a time when one of them was pushing 3-year-old Ana not to enter the house. In all that long way to go to the warehouse it happened that I didn’t even exchange a glance, let alone say hello to anyone. But that was better than having some curious eyes suddenly cast upon you.

They were newcomers to the city, to whom the Lezhian companion hurried to tell them that that woman there was the friend of…! One day, as I was very close to the observer, he came up to me and asked: – “Well, how I look like a zoo animal?” They didn’t expect it. They whispered something in shame and continued on their way.

…Adults, although not so easily, with cold logic had an easier time, but what happened to Ana who, by nature, was a very sensitive, loving child, associated with people, especially children? When Ana could understand that inside the nursery, the caretaker treated her like all the children, and outside, like all the citizens. With shouts of joy, Ana, in the middle of the street or in the store, would let her go from behind, calling Teta…, but the aunt on the street was even more alienated when Ana was with us!

This was also the case with his friends, when they were accompanied by their parents. And Ana found evil in her mother and grandmother, who ran to catch her and then hold her tightly by the hand. He would get angry, get wild, start crying and bite our hand to let him go.

He also cursed us: “Grandma Keche Mandaleche” or “Mami Keche Mandaleche”. It saddened us, but what could we do? Only when we arrived home, she calmed down, asked for forgiveness for cursing us, turned into a loving and good child, not knowing that we too were condemned like her.

When Xija, the nursery school caretaker, said to me: “You’re a little girl”, I didn’t understand. Not because of the dialect, but because that kind of “nymi”, that is, it was about lice, I had almost forgotten it. Although I tried to find the cause, I couldn’t. Outside of the nursery, Ana did not associate with any children. It didn’t even occur to me that this knot could easily be made right there.

It seems that I continued to idealize these institutions, where parents sent their children out of necessity. In the old daycare center, where Syri was the director, this was an episode, but when Ana moved to the new daycare center, to director Drania, it turned into a trauma for Ana, and darkened our lives as well. That’s why I’m writing about it.

The night before, Zana, by order of the caretaker, had spent an hour cleaning Ana’s head. A state of tension, nervousness and disgust had taken over us. The next day I went down with Anna. It was a cold February day. I was in a hurry because I had to go to the Shengjin warehouse.

At the entrance of the nursery, the headmistress was waiting with authority and seriousness. He ruffled Ana’s hair and with a big sigh said to me: – “I don’t accept it, it’s impure”. I told her how I had the job, but she arrogantly replied that she didn’t need it and closed the door.

I headed to the station and on the bus, holding Ana tightly, who was crying, repeating: “There is no Ana mola”, for the first time, after all that had happened to us, I cried. That lack of empathy towards Anna had touched me deeply. How was it possible that such people dealt with children and hurt them in that way?

I told the workers what had happened to me. Jupi quickly lit a fire, next to which we sat Ana, who continued to cry and said: “Ana has no moths”. They took it well and repeated: “No, no, Ana has no moths”. Then Jupi went and bought him a chocolate in town. At 12 o’clock, they told me: – “Go home. Even if Abdullai comes, we tell him.” If the world didn’t have such good people, how would it be!

* * *

Ana

Ana went from nursery school to kindergarten. …But the older he got, the more troubled and complicated his life became. This had nothing to do with the great, constant deprivations he was growing up with. It was a more subtle, more painful disturbance that touched, poisoned the child’s soul, the pure and joyful world, and turned it into occasional traumatic shocks. Father, then grandfather and Mimi (Gimi) ran away and did not return.

Little Anna couldn’t explain it. He kept asking: – Where are they, why don’t they come? – In Tirana, at work – we answered; and she repeated to Tetis: – “Dad is in Rana, grandfather is in Rana, Mimi is in Rana…”! When from the kitchen window, from where he could see “the world around him”, he did not see the hospital’s horse for a couple of days, which usually grazed in the enclosure with railings, he called out to Tet with regret: – “The horse has gone to Rana”.

When he grew up a bit, he began to ask with concern – Grandma, how is my father? I, without any hesitation, immediately and forcefully told him: – Very good, for you it is the best in the world. Enjoyed and calmed down.

… One day Ana came from the garden worried and irritated. Her face was filled with despair and surprise. “Why, daddy Tosi, he is German”? “How cans daddy Tosi be German, isn’t he my son? Is the grandmother German?”

Ana listened and tried to believe this and not what her best friend from kindergarten had told her when they had a fight. Ana’s friend, Gresa, really opened work for us. After a few days, he added “enemy”, “prison”, etc. to the insult “German”. Ana had to get used to it, familiarize herself with the “Germans”, otherwise she would have had a hard time.

We did our best, with a kind of nonchalance, smiling when he complained, to tell the girls that we were not impressed, we didn’t ask about those insults. Another route I used was unsuccessful. I was talking to Anna that there were good Germans; even some of them came to Albania for work, as friends. Ana opened her eyes and turned to Tetis – “Whoa, what does grandma say, shameful words”.(?!)

You have to know what was happening in the garden to understand these reactions. One day Ana didn’t want to go to the kindergarten anymore and she told me the reason. “Ms. Reti always makes me German”, he told me that day. “Why does my grandmother never assign me to recite poems”? He asked with interest. We answered that not all children recite poems, but Ana was not convinced by this, so she continued to insist: “Me, me, why don’t I recite”? Ana was right not to believe.

… But how heavy and painful the visits and separations in prisons were for Anna. In July 1975, he met his grandfather in Burrel. We had gone all four. Ana was constantly chirping, reciting and singing songs to her grandfather, while the numb Teti, even though she was being driven by many cars, only answered with “yes” or “no”. We finished the meeting and when we said goodbye, to part, Ana cried loudly. He did not separate from Todi, he pulled him by the sleeve and told him “Come home with us”!

How he was waiting for the meetings with his father. He watched him from afar as he approached the big iron gate, he clapped his hands with joy, shouting: “Daddy came”. – Passed then in his arms through the counter. What about Tethys? She sat on her knees in a corner and neither spoke nor moved. Was he afraid of the soldiers and policemen who were around? Then dad for him was so abstract. She was only one month old when Fatosi was arrested. Our calls, Anna’s criticisms did not move her from the corner she had occupied.

In separation, only Ana shed tears. They were tears of pain, but surprisingly beautiful. They did not flow down her cheeks, like a stream, but came out like plumes from her eyes and, as she kept her head down, they fell one after the other on the ground. He didn’t speak there, but on the way he asked with the naivety of a child: – “Why doesn’t daddy come with us, won’t those uncles let him?” Then he himself came to the confusion that they couldn’t be “uncle” for him, so he asked: “Don’t those officers let him?”

On October 20, 1976, Ana, who was not yet 4 years old, passed her first big test: She walked down from Spaçi to Rreps. It was 7 km. Ana walked hand in hand with her grandmother, asked about the color of the river, which, because it collected garbage, came as if in ocher color, she recited and asked with fear: “Will the night come?” The lump on mom’s neck was satisfied. “This is how we always come, without a car”, he said. In Rreps, Ana’s questions for the night increased, but, finally, a car that came with troops from Oroshi took us up to Shpal. There we sat on the side of the road and waited. The girls, tired, fell asleep.

A traveler took off his jacket and covered them. Another car, coming down from Fushë-Arrëzi, picked us up and drove us to Mati Bridge. It was night when we left for Lezha. The next day in the garden. Ana did not move from the chair and did not play with the other children: “My soles hurt”, she complained to the teacher. The soles of our feet hurt us and not Anna. Playing with each other, Teti threatened Ana: – “I will put you in prison”. – So Teti went to prison! When we asked her what she meant by prison, Ana answered: – “Why don’t you know”? We answered that we didn’t know, but she shook her head and said: – “Oh, what are you”!

Once I laughed sitting with Ana at the place where “Stop” was written, in front of the big gate of the Burrel prison. A “Zis” truck arrived and Ana asked: – “What are the meals here in grandfather’s prison?” They took them there to dad by truck. For the first time, Ana talked about her father’s and grandfather’s prison. It was growing, getting big, as he liked to say. Now Ana no longer talked about “Rana” and “work” for dad and grandpa, but asked insistently: – “What’s wrong with dad?” Why did they put them there”? The grandmother always answered, briefly, firmly: They have not done anything. Memorie.al

The next issue follows