From Vepror Hasani

The first part

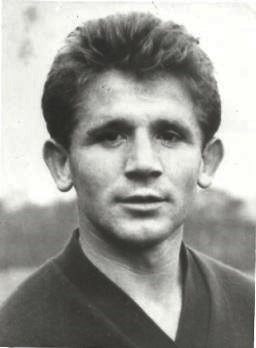

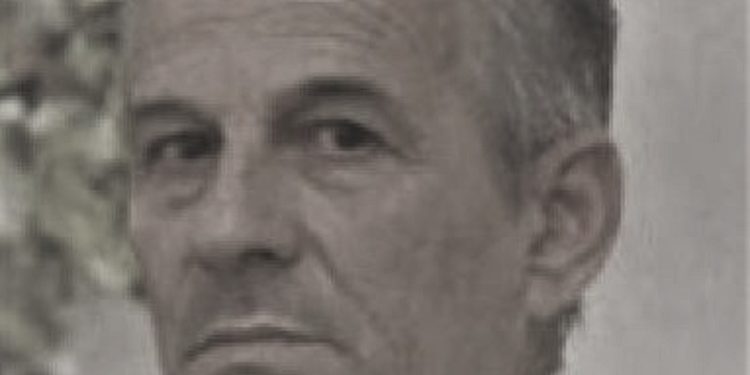

Memorie.al / We had let him meet in one of the bars in Korça. I saw that he was coming with his “Cadillac”, that’s what he called the bike, which he goes out with every day…! After we ordered, “Honored Master of Sports”, Teodor Vaso, decorated with the ‘Gold Medal’ – for outstanding merit in sports -, football player from 1957-1973 and coach from 1973 until today, started to tell me. Recounted one of his football stories: “Everything about my stay in the ‘Partizani’ team or not, was left in the hands of the generals…” he began to tell me.

“Ah, the barbed wire, I will never forget them”, says the “Deserved Master” of Sports, Theodhor Vaso, decorated with the “Gold Medal” – for outstanding merit in sports; football player from 1957-1973 and coach from 1973 until today…! “I don’t know why they stayed in my memory for so long. Maybe those barbed wires are my childhood. Barbed wire appeared to me every Sunday.

It was this day when I was running towards the sports corner of the city of Korça, where the matches between “Skënderbeu” and other teams of the country were taking place. At that time, the football field was called “the field”. They had called it that for the first time since 1925. That part of the field was surrounded by barbed wire. I stopped running only when I reached the wires.

As children, no one allowed us to enter, but we remained hopeful that someone would help us. In addition to the wires, field guards surrounded that territory and entering the “field” was difficult. It was like crossing the border. Every Sunday I was there two hours before the start of the match, but everything was depressing. At that time I was only 9 years old. It was 1950. I was sitting and waiting there. Not long before the start of the match, the adults appeared. They went straight in, no one stopped them. I looked at them with envy. I wanted to be an adult at that moment too. One of them would take a child by the hand and bring him inside. It was at this time that I also prayed: “Uncle take me with you, uncle take me too…”, but they only took any child they knew. I was still there. The torture of being behind bars on many occasions would follow me until the age of 16.”

My father

“My father didn’t come to sports because he had to work to support the family. After liberation, our economy started to collapse. We lived in the time of poverty, we ate corn bread. Our clothes were patched clothes and old shoes. I used to dress and opinga, because they lived more years. We postponed the shortage until today and tomorrow. My father regularly paid the taxes of the shop, where he sold chickpeas, while we had nothing left for ourselves. We lived doing economy in poverty. We shared the bread rations with this. Time passed by postponing the days one by one, anxiously waiting for what tomorrow would bring us. Can you imagine in what poverty we lived! In our house, it used to be when my brother or I had lost a button.

After that, my father also left the store, because we couldn’t do the taxes. He started working as a painter in a state enterprise. After that we started to feel better. We tried to pretend not to look poor. With all the poverty that oppressed us, we kept a pair of clothes for excuse as the eyes of our foreheads. At that time, when I looked at my father among men, my being became happy. The way it was dressed and how it was carried was pointed out to men at that time. For religious, family and national holidays or in case of death, there was only one costume: the one he wore when he wore the wedding crown in the church.

The cloth of the suit was a little lighter in color than the Republic hat, dark blue in color, when the light was not full it looked like black. He wore a field tie with thin red and black stripes. At that time, my father was one of the men who wore a tie and a suit. This way of dressing was left over from the time of pre-liberation. That I was thinking of all this in those moments standing behind the wires. I could only watch the game from there. At first I sat near the dressing rooms. They were located in the southeast corner of the old field, from where the players came out for warm-up and for the game.”

Before the game

“I stood behind the wires and watched from there how many people entered and exited. Only I, (like many other children) could not enter. I watched with envy how the workers of the field, the employees of the “Skënderbeu” club, the judges, the officials, the policemen, the mayor, the police chief and many others moved so freely inside the “field”. Only I wasn’t there. But that was not all. There were days when I felt much worse. This happened in the first game of the season. In such cases, I saw how a group of boys and girls with flowers in their hands entered the “field” to give flowers to the referees and players. In these cases, I thought: “How come I don’t have this luck too.”

The children who brought flowers were selected. This surprised me. I was one of the best students in my classes and had started to show my talent in playing football and in athletics. Why my name did not make any impression! I had an irresistible desire to bring flowers to the players, to touch them with my hands, and then when I left the “field” to tell my friends what they had told me, and what I had told them. I was dreaming. It was no small thing to be inside the “field”, especially when some of the players went out to warm up and were waiting for their other friends to come.

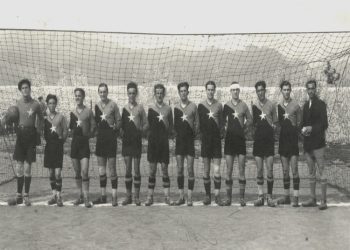

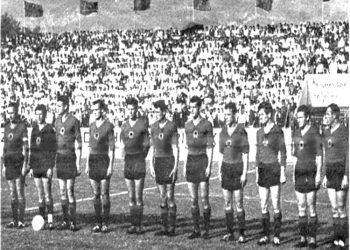

This was a special moment: calls were heard, greetings were heard, noise was made, movements were increased, football players met their rivals, companions, locals, referees, etc. It was a very beautiful thing. After the warm-up, the players put the finishing touches on the match uniform and lined up in two columns, with the 3 referees of the game, they went down the playing field, because the “field” was 5-6 meters below the level of the square in front of the dressing room. Only the first whistle of the “referee” whistle, as we Korcarians called the referee at that time, extinguished that tempting rumble. After that, the emotions started. Blessed is he who crossed the barbed wire.”

Match

“I kept standing behind the wire. Being present at the start of the match was even more beautiful. Every time there were chances for goals, or when our team scored, then from the crowd surrounding the ellipse-shaped field erupted a roar that created the sensation of a hurricane. The roar could be heard in every corner of the city, for its undulating echo spread across the plain, struck the hillsides near the city, and only after a certain time did everything fall silent. Only if you were inside the “field” could you see the “giants” up close, that’s what I called those people who played football. For me, the passes, tricks, crosses and especially the shots that sometimes ended up in the goal seemed a real miracle.

We made “matches”, that’s what we called the matches between mahalla and mahalla for the border areas. We played with a cloth ball, because we looked at rubber balls and leather balls with binoculars. We fashioned the balls from strips of old booty the width of a finger. We took the loot secretly from the lady of the house. The ribbons wrapped around a booty that formed the core. To make it compact and to strengthen it, we tightened it tightly. We made a special connection to make it spherical. Many of the boys were engaged in this craft. There came a moment when I was forced to join the dance. I was already one of the kids who stood out in football and athletics, but I always thought that no one noticed my talent. Maybe they didn’t care.”

Infancy

“When I was not yet 16 years old, I started working as a waiter at the “Republika” bar. The bar was not very busy. It was almost empty all day. One afternoon in June, two men came to the bar. They turned to me and said: We have come for you, if you accept, we ask you to represent our company in our athletics championship. Deep from the soul, a spark broke out that electrified the whole being, excited my cedar. It was the first challenge in life: a banco – test of my sports skills. I led the 800 m race with adults at the age of 16. The athlete Pandi Nika caught me and passed me in the last 5 meters. I crossed the finish line, falling to the ground, but picked myself up quickly. I was surprised. Coaches, athletes and sports fans flocked to me.

Pandi came last, took my hand and said: “You took the title of champion from me”, – then he laughed and continued, – we will see each other in the national championship. It had been surprising to everyone how a teenager could lead the race to the end. After that, in 1957, I took part in the national youth athletics championship. However, my mind remained on football. I always remembered the matches behind the barbed wire. That same year, I started to study in Tirana at the “7 November” Polytechnic. It was Tirana that would give me the name I still have today. However, every time I go back to my childhood memories, I don’t know why I see barbed wire. Maybe they have remained as a part of my life”./Memorie.al

The next issue follows