By Aldo Renato Terrusi

The tenth part

Accueil

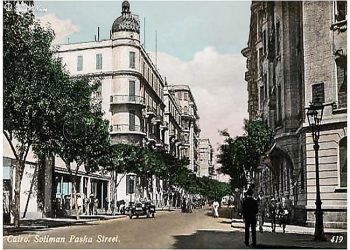

Memorie.al / Fiumicino Airport. Alitalia’s ‘MD 80’ plane is ready for flight. It’s Saturday, November 6, 1993. 11. 25am. The commander received approval. The flight attendants remind us once again to fasten the seat belt. The two engines are brought to maximum power, while the noise becomes muffled and deafening. Buttons and controls are tested one last time according to flight procedures, the brakes are released, the faster and faster movement begins, the acceleration slams the passengers into the back, the plane takes off. I feel an invisible force lifting me up that leaves me suspended in the void. I look around to see if the other passengers have the same feeling as me. Some read, some look out the window, some are indifferent, some barely sit still and some, frozen in their seats, let their fears show. With a wide change of direction, the plane rises in altitude and heads towards the radio beacon of Bari, then straight to Tirana, our destination.

Continues from last issue

The bank of Vlora was closed and patrolled, while the families of the employees moved to Llakatund, a village a few kilometers north of Vlora. Afterwards, Giuseppe was released and the bank started working again, but under the strict supervision of the Germans.

Petriti tells us that the counters, tables and chairs are those of the Italian period. We go upstairs where, many years ago, my family lived. Even though they were exactly the same and they had used them, with the same floors and even the same furniture, the rooms had already been converted into offices.

We enter the main living room in the center of the apartment, from the large window we can see the square of the fountain, and then we go out to the terrace, a witness of many events and vicissitudes.

It was a very sad period for Albania: on the one hand, the National Liberation Movement of Enver Hoxha was against the Government in charge of Zogu, on the other hand, the members of the “Balli Kombëtar” supported Zogu, cooperating with the Italians. Then taking into account that in that territory Italian, English and German troops also faced each other and irregular Yugoslav and Greek troops were gathered on the Albanian border, the situation created was, to say the least, chaotic. On September 20, 1944, Xhuzepe had gone to Tirana for a meeting with the directors of the Italian banks: it was necessary to decide the position that would be maintained in the new situation of the fierce conflict between the forces of the Albanian partisans and the German contingent, which still controlled Vlora.

It was night and Aurelia, always anxious, slept in her bedroom on the first floor of the bank. The waitress and the cook slept on the opposite side of the apartment. Aurelia heard Kri Kri, her white volpino dog, barking from the side of the house facing the bank’s inner courtyard. She heard someone’s footsteps on the terrace and started screaming, waking up the maids, who immediately ran to her. All they could see was the shadowy shadow of someone disappearing as it crossed the surrounding wall. Eugenia, who slept next to Aurelia’s room, didn’t even feel a thing.

The next morning it was discovered that the back door of the bank had been forced open, but nothing had been stolen. The one who suffered the worst was Tu Tuja, the Angora cat that had been stabbed, lying on the floor, meowing softly; only Aurelia’s loving care managed to save him. The Albanian partisans were starting to put pressure on the Italians. A few days later, while it was getting muggy outside, Aurelia was fixing the newborn’s clothes. She was alone, her husband had gone to the Italian Consulate which was not far away, the maids had gone out to do shopping; Eugenia had also run away, to Vitaliano’s house, because Emma was a little out of sorts. Aurelia heard footsteps and angry voices in Albanian and Italian coming from the inner stairs; managed to he recognized the voice of Alberto, who, as he had noticed the presence of the uninvited, was trying to protect the premises of the bank.

There was no one to help him: he could only run away or hide. She began to feel threatened. He decided to run away. Bare-legged and with a seven-month-old belly, he opened the first-floor window, climbed onto the frames, and then, clinging to the bars of the ground-floor window, managed to jump into the street. Holding his breath, he reached his parents’ house and raised the alarm. Relatives went there; the consulate and Giuseppe were notified. No trace of the miscreants. However, they had only taken the little money they had left in the sideboard drawers. The thieves, who were known to belong to the National Liberation Movement, were not able to ‘work’. The next day there was an internal investigation between the employees and the director. It was concluded that: one of the two Albanian employees had ‘forgotten’, as I said, to close the back door of the bank.

An agreement signed between the Bank of Italy and the Albanian Government, finalized in the direction of the local banking network, stipulated that a part of the employees had to be Albanian citizens. The ‘forgetful’ clerk, who had initially tried to blame others, was not to be fired: this was Enver’s order. The insurrection of the Albanian partisans reached great proportions and the Germans began to retreat.”

From one of Giuseppe’s many letters to his sister, Kiara:

“Vlora, 22/10/1944. We have been freed for almost ten days and the German bandits ran away with their tails between the saddles”.

“On November 29, the People’s Republic of Albania was announced with Enver Hoxha at the head. His partisans also liberated Tirana, thus strengthening the government established a month ago with the support of the communist groups of the National Liberation Movement.

The departure of foreign troops from Albania, without the participation of the Soviet communists, further strengthened Hoxha’s prestige.

By assuming the duties as president and Minister of National Defense in the Provisional Democratic Government of Albania, Hoxha became the almost legendary hero of a poor and backward country”.

We enter again and on the right is the room where I saw the light for the first time. The environment is quite well lit, not too big, unfurnished, with a window without curtains. While I flash casual smiles, I hide the emotion that makes my heart beat fast and the blood rush in my veins. I manage to wipe away a furtive tear in time. On the morning of January 4, 1945, after a little less than three hours of labor pains, relatives and friends gathered in the adjoining parlor heard my first cries. Anita and Bruna had a lot of work to do, because they had to provide and calm their grandparents, uncles and friends. Eugenia came out of the room and loudly declared: “He is a pretty boy, everything went well”!

Congratulations and congratulations from the relatives: Giuseppe became an heir! Immediate telegram to the municipality of Castellaneta to confirm the birth of Aldo Renato. Two months later I was baptized and the godfather was Piero Rovigati, the delegated administrator of AIPA and a close friend of the family. It was an almost secret ceremony, because the government was threatening war against the Italians and the surrounding atmosphere was decidedly oppressive.

A few days after the baptism, two inspectors from Enver’s government came to the bank and asked for the director and the cashier. They wanted to verify the account books. Father took them what they wanted. Both of them took a careless look, flipped quickly through the pages, confiscated everything they brought and left without even saying hello.

It was clear that the Italians, although apparently free, were actually prisoners of Enver’s government. And it didn’t take long when, at the end of March 1945, the Albanian police of the National Liberation Movement appeared at the bank with an arrest warrant for the director and cashier, countersigned by Hoxha. The charge was extortion of the property of the Albanian people. Both were taken to the nearest jail. After that, the regime organized a staged trial in which the only witnesses were precisely the officials dictated by Enver Hoxha. The trial, held behind closed doors, lasted almost a month, practically without like-minded defense lawyers: those of the office had only the role of mundane figurants. And those witnesses, Alkani and Balishi, failed to be efficient and managed to shake the body of the accusation. However, Balishi, against any evidence, openly accused the bank of embezzling the money.

From a statement by Enver, years later:

“After the capitulation of Fascist Italy in September 1943, the Nazi army took the Albanian gold deposited at the Bank of Italy in Rome. The representatives of the Foreign Ministry of Germany and those of the Albanian government reached, by means of a protocol signed in the spring of 1944, the recognition of this amount of gold by the Albanian state. As if this was not enough, in October 1944 the commander of the Hitlerite troops in Tirana took the gold that was left in the National Bank of Albania, declaring that he would deposit it in the branch of this bank in Shkodër…!

Although the prosecution demanded it, with the promise of a reward, no one else came forward against Giuseppe and his bank. No Italian testimony was accepted. Some Albanian friends were willing, but they were immediately accused of collaborationism and thus their mouths were closed. Giuseppe was sentenced to ten years in prison. Before they repatriated him, Melisi went to meet him in Vlora prison and told him that his hands were tied. The conversation was quite dramatic: Melissa, Giuseppe’s dear friend, was aware that he could not do anything to help him. Giuseppe, guessing that it was unlikely that he would be released, begged his friend to protect his son Aldo like a father and to help his wife Aurelia, in the difficulties she would face in Italy. Melis promised him that he would do everything his friend asked him; he even called it exactly his duty.

Neither the Bank of Italy, nor the International Red Cross, nor the Italian government, could and did not want to do anything. The responsibilities fell on many different authorities, but no one took them on. It was more appropriate to bury facts and people who could bring trouble to important positions of the Italian state. For his part, Enver Hoxha did not ask for better than that: he had fulfilled his personal revenge against Xzepe and his family. Many Italians and Albanians ended up in prison during that time, allowing the dictator a clear demonstration of power over his own people, who had just emerged, oppressed and divided, from internal and other wars.

Subsequent requests for forgiveness were ignored every time, the Albanian state with the advent of the communist dictatorship closed in on itself like a hedgehog. Over the years, many Italians were forgiven and returned to Italy, but not Giuseppe. I only have a vague memory of my eti, behind the bars of the Vlora prison, and of myself as a child, next to my mother with my hands outstretched towards him. From there, after a few days, we were put on a ship to Italy. I never saw him again.

The family of the caretaker of the building, to whom we briefly explained the reason for our unexpected visit, before greeting us, treated us to a small party, treating us to food and refreshments. We politely wish them a good stay, leaving a very generous tip to both the caretaker and the guard on duty. The villa next door, which was to the left of the bank, is where my grandparents, Vitaliano and Emma, lived together with their sister Ida and her son Domenikon.

We knock on the door and they come to open it for us all curious. Toli explains the reason for our visit. The hospitality is very cordial and friendly and a mutual sympathy is immediately created between us, especially when we tell them, through Toli, that we lived in this same house 50 years ago. The villa is very modest, almost dilapidated. We tour all the spaces from start to finish: the dark and good kitchen in the living room, with the fireplace, the winding wooden spiral staircase that leads to the two upper rooms, in one of which my mother and I lived for several months when we left the bank before we were transferred with the whole family to Tirana.

A photo gram blooms in my memory: the fireplace of the living room was the object of my mock-up projects.

One thing particularly attracted me. It was a mysterious, metallic, very heavy, Gothic arch-shaped, red and blue object that stood out very nicely on the upper side of the chimney. One day, with the fireplace extinguished, I clambered over a chair to grab that much-desired object, with great effort I scrambled to retrieve it, but it overturned and fell to the floor causing a great crash. Grandma came immediately and found me still standing on the chair, while the object that had been a mortar shell rested on the broken floor tiles. What was inside was spread all around: nails, screws, washers, twine, etc. It was a decommissioned piece of war junk that Domenico, my fourteen-year-old cousin, had found and then carefully painted and finally filled with all his treasures…, black that touched it!

From that day, despite Domenico’s complaints, the bomb became my favorite toy. The dilapidated furniture we see is probably the same from that time. Everything seems to have remained as it was many years ago, except for the secret closet under the stairs, where a pistol was walled up to prevent the Germans from taking it during their raids, or accusing the family of terrorism and espionage, with possible consequences I think. Now instead of this niche is a niche with a sign. As we leave the apartment, we also take a look at the uncultivated yard and the dry well. Daja remembers that in that place, to escape trouble, they threw away two rifles and two swords immediately after September 18, 1943. We leave with the same cordial and ceremonial greetings of the occasion.

“Come visit us again”.

“Maybe someday, who knows…”!

We head to what used to be the Italian Consulate of Vlora, a massive building that stood out in dark color; the main door of which was equipped with a graceful portico in the classical style and which was currently uninhabited. The old prison, defunct for years, is located just opposite. It is a modest two-story light-colored building with large cracks in the exterior walls. The green wooden gate is locked with chains; on its sides are the windows of the guard post. Petriti shows us the barred windows on the upper floor: all the cells were there.

“In this prison in 1945, all the bank officials ended up, including the director your father, the cashier and many others. Even before they were sentenced, they had been imprisoned and beaten in a single cell, she cried. After a few years, they were separated and so I ended up in his cell with two other Italians whose names I can’t remember. That same year they sent us all to Burrel”.

Uncle asks Petrit to take us to the easternmost side of the country, where great-grandmother’s house used to be. On the way there we see a very large square with a large and beautiful mosque in the center. Around it there are modest houses with worn and damaged walls. We go to one of them and knock. After a few seconds, a voice is heard in Albanian, incomprehensible even to Petrit himself. We wait. The door opens slowly and an old woman appears, dressed in peasant clothes, fat, uncombed, sleepy, who starts talking to Petrit.

After a few moments he lets us in and lets us tour the house. A hut with two small rooms, one serving as a living room and bedroom and the other adapted for a kitchen with an adjacent bathroom. They were both seized by a pungent odor coming from the nearby sewer. We greet the old woman and quickly leave that depressing place. In front of that house is a small hill, which Xhakomoja says is the site of the Old Catholic cemetery destroyed by the partisans in 1943, in which Lilino’s body was buried. Memorie.al

The next issue follows