By Hajro Hajra

The first part

Memorie.al / An authentic narrative, lived and unadorned, drawn from the carved, but not sleeping, memory of the Albanian who experienced the communist hell, but who managed to escape from that hell thanks to the resourcefulness and great faith that only by coming out of that purgatory, you can fight that icy winter, that infernal fog that had covered Albania from corner to corner, you will read in this article about Remzi Barolli, sentenced to 101 years in prison by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha.

Childhood village

Tresteniku, a small village in the district of Korça, where he was born, reminds Mr. Barolli of the village from which his ancestors had fled, a village which according to the notes of the Austrian lieutenant colonel Paul Joseph Mitesser, in 1784 had 60 houses (43 Albanian and 17 Roma and Armenians). That town, from which the great-grandfathers of Remzi Barolli were forcibly moved in the winter of 1877-1878, land with over one hundred and fifty thousand other Albanians from 600-700 settlements of the then Albanian lands, is located in the northernmost point of Albania Ethnic. That former Albanian town, today is a city in Serbia, has nearly fifty thousand inhabitants and there is probably not a single Albanian.

Even today, Mr. Barolli fondly remembers that Korçar village, where he spent his happy childhood. The days of his childhood had been the only days that he and his family had lived without any great worries, without the troubles that would follow, especially in the years of the brutal communist rule. It was the time of the regime of King Zog, whose figure Albanian historiography has evaluated in a very contradictory way: sometimes as a satrap who drank the blood of the people, sometimes as a dictator at the head of an anti-popular and anti-national regime, sometimes as a King who came to the Albanian throne with the help of his Slavic neighbors, sometimes as a traitor who sold Albania to Italy, sometimes as a statesman in whose time Albania, however, had made a progress, as much as a state could progress in that time of poverty and misery in the Balkans.

Barolli remembers the time of King Zog as a good period not only for the Barollis, but also for the entire Albanian people of Albania at that time. Although the Albanian state was faced with many problems, inherited from the long period of Turkish rule and accumulated during the few years of Albania becoming a state (although it was only a half-state), the people were shaking little by little from that oriental mold of the five-century Ottoman rule and was slowly returning to the West, to which it belonged.

The connections with America are ghastly for the Barollis

Kurbeti, this painful wound of our people, for many Albanians had been the only possible way to ensure their existence. The two uncles and Remziu’s father had also tried the bitter exilebread. The eldest uncle, Demiri, had taken the path of the Kurbat since 1914 and settled in America. Two years later, Remziu’s father, Rakipi, also took the road across the ocean, while in 1917, his other uncle, Murat, also came to America.

The Barolli brothers had worked in America for several years and, after having created some wealth, in 1928, that is, the year that Ahmet Zogu had proclaimed the Albanian Monarchy and was appointed King of the Albanians, they had decided to return to Albania. With the savings accumulated in America, they had bought a large estate, a third of which, after the war, would remain outside the borders of Albania, in Greece.

The Barollis were from those noble and generous families who were not only satisfied with their own well-being, but also cared for others, often even more than themselves. By working the land, they had provided a good life not only for their families, but also for many other fellow villagers and for a short time they would become one of the most respected families in the Korça District. As a member of such a prominent family, in 1932, Remzi’s uncle, Demiri, was appointed sub-prefect of the Korça District, while Rakipi’s father, a few years later, would serve as an officer in Zog’s army.

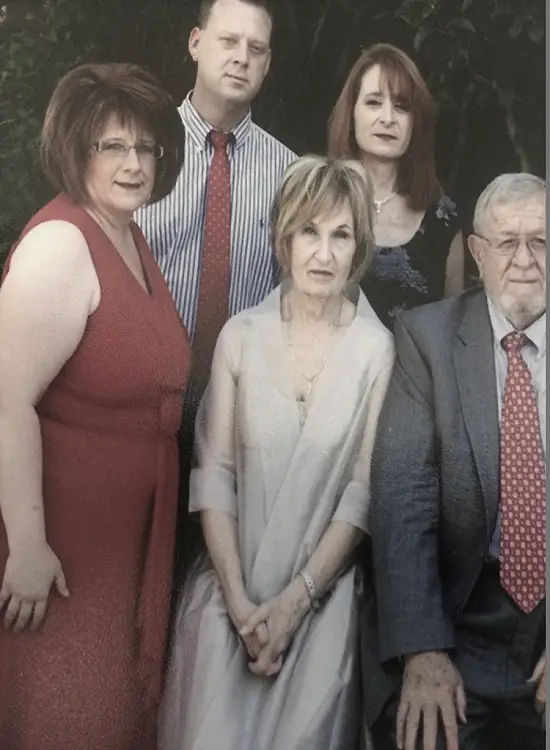

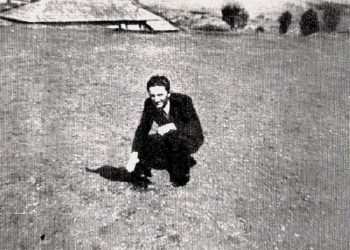

Exactly at the time when the Barolli family was getting lucky, Remziu was born (February 23, 1930), one of the five sons of Rakip and Aishe Barolli. Childhood and early youth are the only two periods of life that Remziu spent in Albania. One, that of childhood, one of the happiest spent in the Motherland and the other, the period that begins in late childhood and ends in early youth, one of the darkest of his life. Today, this gray-haired man remembers those two different eras of his life like this: – ‘When I was a child, I felt like a mountain bird, flying freely and, flying, dreaming of conquering the world…! However, there came another day, one of those that are never forgotten for the living, a curse of the devil was unleashed on all my people and plunged them into an endless darkness’!

The beginning of vicissitudes

The period of a part of the war, of that War that one quarter of people called liberating and others conquering, the Barolli somehow survived, although the omens of a storm against them had appeared from its beginning. During that war, the Barolians were lined up on the side of those forces fighting for an ethnic Albania, which would extend to its natural borders, for a western democratic Albania, for a strong economic Albania. The ordeal for the Barolli had begun before November 29, 1944, the day when half-Albania was “liberated”. It was January 1944. A cold winter day. Although Korça and its surroundings have a mountainous Mediterranean climate, that winter was wilder than usual. The “liberation forces” that were in pursuit of traitorous gangs, as they called those who disagreed with the establishment of the communist red order in Albania, were even more ferocious and more feverish.

In the morning of that frosty January day, communist partisans knocked on Rakip Barolli’s door. Those sad crises in the Ag of that day had been heavy, especially for Rakip’s six children, (five boys and one girl), the eldest of whom was only 15 years old. Those uninvited guests didn’t last long: they had forcibly grabbed Rakip and dragged him out of the backyard. They hadn’t taken more than 20 steps from the courtyard door and heard three gunshots…! When the people of the house came out after a few moments, they found Rakip drowned in blood near the door of the courtyard. This was just the beginning of a tragedy that was knocking on the doors of the Barols.

The Barolli family, and not only her, were living with the anxiety of waiting for what tomorrow would bring. They seemed to foresee a great storm at that time full of surprises. Word had begun to circulate about their collaboration with the “enemies”. Their lives were becoming more and more precarious. Movements had begun to be limited. At every step they felt endangered. Thus, the life of Remziu, who had just turned fourteen and who, although he was very smart and due to the circumstances had managed to finish only three classes of school, was entering that phase which he himself describes as the darkest part of his life.

The arrest of Aisha’s mother

Those were the days on the eve of the “liberation” of Albania. The long-suffering Albanian people were hoping that with the end of the War, good days would come for them as well. That long-awaited day, which, ironically, coincided not coincidentally with the day of the liberation of the former Yugoslavia, was welcomed by some Albanians with joy, but that day that should have marked the beginning of a new season, was marking the beginning of a long winter.

Only 9 months had passed since that terrible day, when the communists had killed Remzi’s father. In October of the same year, the same people in uniform knocked on the door of the Barollinje. Remziu’s mother, mother Aishja, had delayed until she had opened the door and, after she had opened the door, so frightened, because she was worried about the little children, the people in uniforms had rushed in like wild beasts:

– You are hiding someone inside, that’s why you didn’t want to open the door, – they had told her and then, after making a mess of the house looking for the “enemies” sheltered there, they had taken mother Aisha with them, accusing her of hiding enemies of the people in her house (although at the time of the search, there was no one in the house, except for her and her six children).

That October day for Remziu’s mother had been the last in that house. Although she had reached a very old age, she had never set foot on the threshold of that house again, because after her arrest, her children had been kicked out of the house and her house had been confiscated, just as the “people’s power” had done with many houses of “enemies of the people”.

Accused of hiding the enemies of the people in her house, she was sentenced to 10 years in prison. After 10 years of serving his sentence, he would be accused of another crime, which would be followed by another and so on…!

He will spend most of his life, from 1944 to 1990, in prison and exile. Even when he was released (it was the time when the movements for the overthrow of communism had started), he requested to be kept in prison, because he had nowhere to go. All the Barrollites, those who had escaped alive, were homeless. Even those of her family from her father’s side had suffered like the Barolli, so her only refuge was the prison, where she had spent almost half a century and where she had become so acclimatized that she could not leave it.

It was the first time in Aisha’s mother’s life that a request in her favor was approved. It was the first time they had offered him shelter and not kicked him out of prison.

Looking for a roof over your head

The day they handcuffed Aisha’s mother (it was a cold autumn day, with a torrential rain and a piercing wind, Remzi Barrolli remembers today that day, which he can never forget), Her six toads had kicked them out of the house saying: – Go away, there is no place for you in Albania!

They had been ordered to vacate the house without being given any time to find a solution. And what solution could those remaining filikas find alone, without the support and without the help of anyone. It was that day when the endless sufferings of Remziu and the other children of Rakip and Aisha Barolli would begin, sufferings that even today Remziu remembers with sadness. Confused and shocked by the unexpected, left on the big road, the children did not know what to do. They had gone to seek shelter from acquaintances and relatives, but no one wanted to open the door for them.

They had no courage, because they could suffer like Rakip Barrolli, who was executed at the door of the house, or like mother Aishja, who was handcuffed and thrown in an unknown direction. After a few days of wandering, they were settled with a cousin. In order not to be noticed, they were forced to remain confined day and night in that house. Since Remziu was very lively (his friends nicknamed him ‘Furtuna’) and it was difficult for him to stay inside, one day he went out and, that day, thanks to the “vigilance” of the loyal sons of the party, they investigated him and they had reported to the police. The police did not arrest the children, but they were threatened that if they were arrested again, evil would eat them.

At the time when the 6 children were wandering around the villages of Korça to seek shelter, the police and the Albanian army were looking for other Barolians. It was the time when the partisan communists were euphorically celebrating the “liberation” of Albania. And, while they were celebrating, they were pursued by enemy “gangs”, some of which they would capture and after a formal trial “in the name of the people”, or without a trial at all, they would be sentenced to the most severe, including many death sentences. They would also capture Remzi’s three uncles: Demir, Murat and Kamber. The first one would be killed in prison after 4 years of serving his sentence, while the other two would end their lives in prison. Murat died in prison after serving a 30-year sentence, and Kamberi, also in prison, after serving a 35-year sentence.

The children kept looking for shelter, but where to go, who to risk…?! They had decided to go to my uncle. He had just seen them, he was terrified of fear: – They can kill us all; – he had told them very worried and wanted to expel them.

– My uncle’s wife was a wonderful woman, a very brave woman, – Remziu confesses. She took us, took us inside, with all the great fear that uncle had.

Even there they had been forced to stay illegally. They had waited until they had been discovered and again they had strained to take the world in their eyes. Before the police came, the grandmother had taken them from their uncle’s house and taken them to a village 5 km away near Pogradec, to her two sisters who were married to two brothers.

Voluntary work

Even there the attitude was not safe, especially for the “uncomfortable” Remzi. A few months later, he was interned and sent to work in the so-called youth action for the construction of the Kukës-Peshkopi road, whose work had begun in 1946. Even though he was exiled, working in a “volunteer” action, he was deceived by the hope that the persecution of him and his brothers and sisters, who continued to stay illegally with his grandmother’s sisters, would stop.

After a couple of years of working for the construction of that road, together with other “volunteer” shareholders, most of whom were from “enemy” families and where the living and working conditions were very difficult, Remziun (also the son of a family “enemy”) send him to another work action, this time in the construction of the Peqin-Elbasan railway (completed on December 22, 1950).

Even in this youth action, Remziu and the other activists were removing the black olives, because the conditions in which they worked for the opening of the railway track and for the performance of other works were miserable. In addition to working with primitive tools, the shareholders had certain high work rates, which they were obliged to fulfill.

While Remzi Barolli was doing mandatory work in youth actions, other Barolli were being arrested one after another. In addition to the five brothers and sister, many of Remzi’s cousins, close and distant, all of the Barolli family, will be imprisoned, but other families, who had any kind of kinship with the Barollis, will not be spared either. Remziu, who had just turned twenty years old, was living a collective life among “actionists” from different districts of Albania, interned in labor camps. There, Remzi Barolli received notifications about the arrest of a relative almost every day, so he felt more and more isolated from the world. Memorie.al

The next issue follows