By Bashkim Trenova

Part fourteen

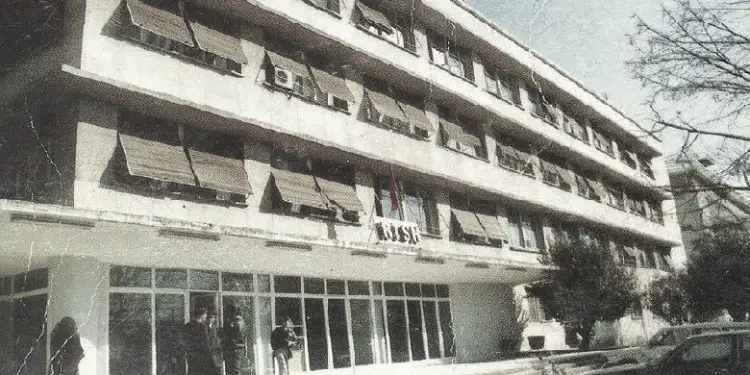

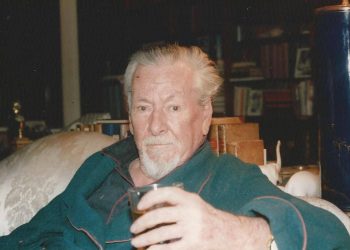

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed as a journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the war period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘People’s Voice’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances met some of the ‘reactionary families’ and their suckling’s, whom he described with a rare skill in a memoir book published in 2012, entitled’ Enemies of the people ‘and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

“Enemies of the people”

How was my colleague from Radio Tirana sentenced to 8 years in political prison?

The dictatorship also hit hard the families of the relatives of the person who had fled or had attempted to escape. Practically their lives were eventually ruined. By Decree no. 5912 of 1979, the People’s Assembly of Albania decided: “Internment and deportation may also be imposed against family members of persons fleeing inside or outside the country. “Family members are persons who, at the time of escape, lived with the fugitive, such as spouse, children, parents, brothers and sisters, as well as other persons who lived with him and were in his custody.” This entire monstrosity was therefore lawful, declared. The truth is that the dictatorship did not respect, in fact, even its laws. Its savagery was above the law, no matter how inhuman it was.

But let me get back to Glinka. His dream was killed and his life was crippled. He was arrested and charged with agitation and propaganda against popular power, which was not true at all. Glinka was a smart boy and he knew very well that after the shooting of his uncle and the imprisonment of his father, as the only weapon of protection, he had only complete silence in front of everyone and everything. He was arrested even though he was silent and only silent. Perhaps, according to the practice of the time, he should publicly condemn his uncle and father, as traitors and conspirators and not only that, but also testify against them. Glinka, for sure, has been silent here as well. This was the fatal silence for him. He, if I am not mistaken, was sentenced to 8 years in prison.

Meeting with the former colleague, after getting out of prison and visiting his house!

I met Glinka after she got out of jail. We met opposite each other on a small street in the beach of Durrës, where I had gone with my family to spend the summer holidays. I was already married and also had a daughter, Bora. I invited him to have a coffee together. He hesitated at first, and then admitted. He hesitated because he did not want to see us together and for me to have any consequences from meeting him. Glinka told me about prison life. As he told me, he had escaped alive, only thanks to his physical preparation, thanks to the barbells. In prison, gangs and individuals were created and manipulated by the official authorities, used to eliminate someone quietly, without trial. In the end, a report was drafted that presented the murder as “the result of a banal quarrel between imprisoned criminals”.

You had to either join a gang, or be very powerful yourself, Glinka told me. This testimony of his reminds me of him, every time on the small screen of the television I see a movie in which the events take place in prison premises, just like in his prison years. Glinka told me that after prison, he was not allowed to live in Tirana. He was located in Durrës. He invited me to his house. My wife, Desin, and I paid a visit. Glinka was also married. We met his wife, a resident of Durrës, a very good woman. She was worried that, being somewhat old, she probably would not have had the good fortune to have a child. Fate helped her and Glinka have a child, a girl it seems to me.

During that summer, Glinka came daily to the beach of Durrës. He left us his sun umbrella when the beach was over, to look for him again the next day. An old friend of mine looked at us both one day. According to him, as he later told me, I was being careless, waiting for Glinka in the apartment where I had decided to spend the summer holidays. Today I judge that he was not wrong with his advice. My enemy’s friend is my enemy! Glinka was an enemy of the Party and my friendship with him made me, automatically, an enemy of the Party. I neither was nor could I think I could be seen as an enemy of the Party. I just wanted to be human.

I met Glinka again when the Democratic Movement started. He came and met me at the “Democratic Renaissance”. With the fall of communism, Glinka was finally able to return to Tirana and start working again for the Albanian Radio-Television, no longer as a journalist, but as chief of staff. I do not remember how long he stayed in this post. I know that he continued to build the Tirana-Durrës road every day and vice versa. Was Glinka disappointed by the beginnings of democracy in Albania? I cannot say anything for sure. However, he left Albania like hundreds of thousands more, on the eve of democracy and like hundreds of thousands in the years of democracy. He settled in the United States.

In the fall of 2010, my wife and I went on vacation to Albena, Bulgaria. One evening in the lobby of the hotel, I was struck by the portrait and physique of a slightly gray man. He resembled Glinka incredibly. I told my wife, to see from there where maybe Glinka was real. “Hey, I said, is it Glinka?” Go and ask, she told me. I did not take this step for fear that I would disturb a complete stranger, for fear of being found like a loser in the hotel lobby. I did not think that Glinka had come to Albena from the USA to spend the holidays like me! This was also my last “meeting” with the real Glinka or, at least, with someone who could very well become his girlfriend.

The sad fate of my colleague, Enver Muça, from an anonymous letter!

From work, many others with whom I, Glinka, Berti, Dervishi, Arshini, Lulzimi or Bardhyl had worked, would be followed and left in the following years. He would be expelled from the Party and Enver Muça would be left unemployed for a while. He was even helped by a coincidence, which did not leave him unemployed for the rest of his life. The Party comrades did not want him to know that he had a wife, Violeta, a rare, very ill woman. She was living her last days. Enver also had a minor daughter, Edlira, whom he would have to care for as a father and mother.

Enver has a life as rich as it is miserable, full of humor and full of sadness. He studied abroad for several years, initially in Krasnodar, southern Russia, where from July 1959 until the end of 1961, he studied to pilot the MIG 19 military aircraft. He returned from Russia like all other students. Albanians, after the breakdown of relations between the two communist parties and our two countries. He stayed very little in Tirana, about 15 days. At the end of them, he went to China to continue his interrupted studies in the Soviet Union. In September or October 1966, when the ‘Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution’ had reached its peak, Enver returned to Tirana. The Chinese repatriated all foreign students.

After returning from China, Enver worked for some time in an office of the Central Committee of the Party. He, along with two or three others, had to translate into Chinese the report that Enver Hoxha would deliver at the next Labor Party Congress. This translation was made for Comrade Kan Shen, the Chinese Security Chief, who represented the Chinese Communist Party in this Congress. After this service, who does not know why he was left unfinished, Enver comes to the Foreign Radio, where he is appointed editor. I remember him in the early days of work, wearing a blue sweater, probably bought in China. We would soon realize that he was in an extraordinary, innate mood. The years he had spent in China had added a new baggage to this delicate but quite amusing, quite successful humor.

I remember when in our office in the newsroom, he imitated classical Chinese gymnastics with incredibly light and at the same time incredibly cut movements, of arms and legs and jumps in the air. He accompanied all this with a call in Chinese, which seemed to drop from his depths. I also cannot forget the lively imitation and comic elements from it, of the Russian Cossack dances at Agron’s wedding, in front of more than a hundred guests. Enver had remained the same, as in his high school years. I remember, years, many years ago, when I was still a high school student, one day Alfons Gurashi, coming in a military suit to the school yard. It was Enver’s military suit, who had gone to study aviation in the Soviet Union and had returned, perhaps with permission. Enver was with Alfonsi. It was a bold joke, but Enver would never miss it. He, despite the worries and tragedy of his life, would always remain such, a man of a brave and inexhaustible humor, for whom we needed so much in those years of dictatorship, but who himself brought misfortune .

How was Enver Muça stopped from going to China, as he was suspected of being a KGB agent?!

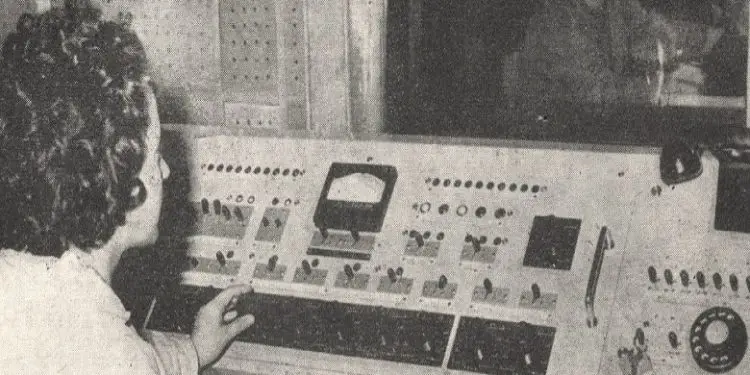

Enver did not stay long as a journalist. He could not stay long in a job. After the Foreign Radio, he moved to the Albanian Radio Television as a tele controller. From life as a telecommuter, I remember one of his trips to Finland, where he went to shoot the football match between our national team and the local one. When he returned, I asked him about his impressions of Finland. “If there is paradise in heaven, Enver told me, on earth it is in Finland?” Such an assertion was quite dangerous for the time, because it praised a capitalist country, which as such should definitely only be filled with incurable wounds like unemployment, poverty or misery of the popular masses, etc., etc.

Even as a telecommuter, Enver did not last long. Sometime in 1974 or 1975, he went to the Foreign Ministry to make the necessary preparations, having been appointed diplomat at the Albanian Embassy in Beijing. When they had two days left to go to Beijing, they called him and said, “Enver!”You will not go to China.” He anxiously goes to Foreign Minister Nesti Nase, and asks him, why would he not go to China? The answer of the minister was: “Do you believe me, Enver that I do not even know the reason why you do not go to China”?! And who knows, Enver asked in a muffled voice?! The Minister pointed to the offices of the Central Committee of the Party, which at that time were located opposite the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Here, in the Central Committee of the Party, an anonymous letter had arrived, stating that 14 years ago, when he was in the Soviet Union, he had a friend of a Russian officer, who was suspected of being a KGB officer. So Enver had entered the circle of suspects as a possible agent of the Soviets.

Anonymous letters could be such, but at the time they could also be improvised as such. If the Party needed them, such a letter was irrefutable proof, effective enough to destroy life, career and dreams. To understand the importance of anonymous letters, when such a thing was needed, suffice it to mention, that the dictator himself had declared that he began the working day by reading them!

Later Enver will also be included in the circle of possible Chinese intelligence agents. In fact, he has an incident with a Chinese spy, which he handed over to the relevant Chinese authorities. For this he was received and thanked by the Chinese Prime Minister himself, Chu En Lai in China and by the Minister of Education in Tirana, Thoma Dejlana, who thanked him on behalf of Enver Hoxha. Now in Tirana, thanksgiving was turning into accusations. Enver will also be included in the circle of potential agents of the UDB, the Yugoslav secret service, because one of his uncles had been for many years the Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs in Skopje, the capital of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. So, if the Albanian Prime Minister, Mehmet Shehu, was accused of being a pole agent and he paid for it with his life, Enver would be suspected of being a pole agent, whom he would also pay dearly in life, and maybe he would have paid as well. With life, if this were to be judged by the “gods” of the dictatorship of the proletariat, who did not cease to “produce” agents and poli agents. However, these belong to a later time, which we will talk about.

The dismissal of Enver Muçë, because he had humorously kept the minister!

After the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Enver started working as a journalist in the magazine “In the service of the people”, which was published by the Ministry of Internal Affairs. To occupy this job, I think he helped Agron Çobani. Agron’s brother-in-law, Feçor Shehu, was Minister of Internal Affairs. One of his conversations with Feçori made Enver start working “In the service of the people”. Here he was accepted as the Labor Party candidate. The internship, i.e., the test to be accepted as a member of the Party, Enver would perform in the Tirana Branch of the Interior, which was a branch of the Ministry of Interior in the capital. He would never pass this “test.” By the end of May 1982, Enver was expelled from the Party and fired. The criticism and accusations leveled at him on this occasion were both grotesque and banal, but enough to bring a man to the ground by the end of his life.

The Minister of Interior, Feçor Shehu, liked Enver’s humor as much as anyone who knew him. His humor was irresistible, incomparable. Since Enver was also his brother-in-law’s friend, Feçori had invited him to the table on some occasion, where they had returned a glass. Who would not have wanted to be in Enver’s place, at a table with his minister? And, after all, would Enver or anyone else have dared to refuse an invitation from the minister? Well, all those who would like to be in Enver’s place, stood up at the meeting of the organization of the Party of the Internal Branch of Tirana, to accuse him that with his humor, he had amused the minister, who was not enemy, but that would be declared a sunny day enemy!

Enver came to the “Voice of the People” editorial office to meet me in those days; I believe the most difficult of his life. He knew that neither I nor anyone else could help him, yet he wanted to talk to someone, to show that he was completely innocent, just as he really was. Then I saw him on a case on the street, near the “Voice of the People”. He pretended not to see me. This was the unwritten rule, followed by others before him, which would be followed by Agron Çobani and me later, although not in the same circumstances as them. This was done so as not to embarrass friends and acquaintances, not to endanger them by exposing them as friends of the enemy! Then I accepted this “ignorance” from Enver, I did not try to speak to him, or to say at least “good morning”, or to greet him without words, just with a nod. Years later, in the meetings with Enver, I always remembered this case, this denaturation of humanity.

Enver himself, in the conversations I had with him afterwards, told me that he, when he left the meeting of the Party organization, was sitting somewhere completely alone, with only one thought in his head, suicide. He even loaded the pistol and put its muzzle in his head. “I did not think of anything, Enver told me, neither his wife, nor his daughter, nor himself.” If he did not commit suicide, he did it alone, because that would give “arguments” to those who accused him, to “prove” that they were right in their accusations! He lived to prove even so, that he was innocent.

To prove his innocence or even his devotion to the Party and the dictator, Enver immediately burned dozens of books, photographs and various souvenirs, which he had brought from the Soviet Union. To show that he was “partisan” and not an enemy of the Party, he bought the complete work of the dictator, ie 19 works on different pages of which, although he had not even read them, underlined different phrases, or wrote on the side with a pen red: “Correct! How beautiful … Very well … wonderfully expressed”, etc., etc. These, says Enver, I did “so that when they arrested me, during the search, they would find these notes and think how much he” loved the Party and comrade Enver “! At the same time, Enver took care to highlight in his home library, Chinese books, and photos with Albanian and Chinese leaders. We were in the “honeymoon” of Albanian-Chinese friendship. When it was over, Enver had to burn them too. The Communist Party of Albania would denounce Mao Zedong and the Communist Party of China as traitors. Preserving them posed the same danger as preserving postcards or souvenirs from the Soviet Union.

Surprisingly, after three or four months without a job, Zef Lokja, a candidate for the Central Committee and director of the Tirana Directorate at the Ministry of Interior, helps Enver to get a job. His wife worked as a chief of staff at the Fruit and Vegetable Company. She hired Enver as a storekeeper in a fruit and vegetable warehouse. Enver was lucky! Now he had a salary to keep his breath alive, to feed his daughter, even though he was a man with two professions, with two foreign languages, with work experience as a journalist, etc., etc. Enver worked here from August or September 1982 to 1991. This was one of the most difficult periods for Albanians. In the market in these years everything was missing. People lined up at two or three in the morning to buy something. When the market door opened, the crowd rushed in, knocking down elderly people and mothers with children, to buy ten eggs. They were more valuable than a human life.

With the beginnings of democracy Enver changed his name placed on the front door of the apartment where he lived. Instead of “Enver Muça”, he decided “Enver Muti”. It was the same revenge against the dictator, who was also called Enver. Even during the dictatorship, Enver Muça made fun of “Enver Mutin”. He also provoked a friend of his, calling him by name and adding after “Muti”. When he was angry, Enver said to him: “What do you have? You also call me Enver Muti”, but where did he keep the other one shouting “Enver Muti”!

With the establishment of democracy, Enver worked for some time in SHIK (National Intelligence Service), then left there himself and opened a brewery, which he called “Tek Gota” as in the famous novel “The Good Soldier Schweik” by Hashek. He returned to SHIK, from where he retired. Edlira’s only daughter is far away, in Greece. He lives alone with his wife, Nora, a strong, courageous woman, life partner and irreplaceable humor companion in the years of endless worries.

The other colleague of the Radio, Zefi, who, like Enver, suffered from an anonymous letter!

Enver Muça was not the only one of my friends and colleagues at Radio Tirana, whose life began to take a different direction from an anonymous letter. Even, before Enver, it is Zef Gjoni, who feels hit as a result of an anonymous letter.

Zefi was a man without many words, but with many human feelings, very friendly. We worked with him in the East Editorial Office. Here on Radio, he met and fell in love with a technical, agile, tall girl. Everything was rosy for Zefi, until one day he was waved in front of an anonymous letter, in which he was accused of hiding something from the biography of his family or tribal circle. Here everything was rolled back. I was in Uznova, Berat at that time. From a letter sent to me by Enver Muça, I learned about his departure. “Zefi, wrote Enver, left Radio, in Shkodra. I was very sorry, but …”! He was fired from the Radio and sent, as far as I can remember, as a teacher to a lost village in the north. Love, career, plans to build a healthy family in the capital, for a quiet life, all crumbled under the weight of this letter. Memorie.al

The next issue follows