By Bashkim Trenova

Part nine

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the war period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘People’s Voice’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances met some of the ‘reactionary families’ and their sucklings, whom he described with a rare skill in a memoir book published in 2012, entitled’ Enemies of the people ‘and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

“Enemies of the people”

Students from Kosovo in our course at the Faculty of Philology

In our course we had seven or eight students coming from different cities of Kosovo. They had left Kosovo because as Albanians they were persecuted, denigrated and oppressed. Simply being Albanian ranked them on the side of opponents of the Belgrade regime, “affected” or with bad biographies. Albania was their dream. The reality was quite different. They fled Yugoslavia to escape persecution, so as not to be forced to report their relatives, friends and acquaintances to the police authorities. In Albania, for one reason or another, one of them testified in the courtroom against the “enemy”, who was none other than a friend or companion of their suffering.

Among the Kosovar students in our course, were also Ibrahim Ferizaj, Laho Gashi, Rrahman Berhani, Sabri Zeqiraj, etc. All of them, except Sabri Zeqiraj, graduated. Sabriu died, if I am not mistaken, in the second year of studies. He did not resist to the end. His health was deteriorating. He had crossed the ordeal of the island of Goli Otok, also known as the ‘Yugoslav gulak’, where the Belgrade regime imprisoned and isolated its most dangerous opponents. Their treatment in Goli Otok, as Sabriu told us, is reminiscent of that of the concentration camps set up by the Nazis during World War II. According to records referring to Vladimir Dedijer, the biographer of the then Yugoslav leader Tito, 3,800 people were left in Goli Otok. The prisoners of this camp have been subjected to physical and mental torture. In addition to killings and suicides, planned starvation has been implemented; there have been occasional outbreaks of dysentery and hepatitis. Nowhere on the island is there a cemetery for those who lost their lives there. Their bones are either hidden under white stones or ended up as food for fish.

Sabriu died at Tirana Hospital, if I am not mistaken, of hepatitis. Although he failed to pass the diploma exams, his photo is among others in the multi photo of our course made at the end of studies. We decided she would be by our side. We did not want to be “allies” with death, which cut the dream between Sabri, who did not allow him to be with us in the emotions of the last exams. Despite our desire, the photo of Sabri Zeqiraj, however, differs from the others. She is surrounded by a black ribbon, just as his busy life in the well was surrounded.

Agim Gjakova, Sulejman Krasniqi and Myrteza Bajraktari, students in Tirana

In the Faculty of History-Philology, during the years 1962-1966, there were Kosovar students, who attended other branches, besides that of History-Geography. Some of them studied Albanian Language and Literature, others went on to study English, etc. Among them was Agim Gjakova, who soon became famous through the publication of his poetic volumes. He looked proud and disrespectful. Sulejman Krasniqi and Myrteza Bajraktari also studied Albanian Language and Literature.

Suleiman was different from Agim, more robust, more energetic, and ubiquitous with his gurgling conversations. He was very young, he had tried the prison cell in Kosovo and, as if that was not enough, even after escaping from Kosovo, after spending 13 days in Tirana prison, he tasted the bitter taste of internment, labor camps in Seman and more than in the village “Shtyllas” in Levan of Fier. Suleiman also became quite famous with the publication of several historical novels, which deserved the attention and appreciation of the reader and were honored with high literary awards.

Through the press I learned that Agimi has returned to Kosovo. I also learned that Sulejmani, the “bulldozer” of actions we did together as students, was gripped by a partial paralysis. In this condition, very sensitive, almost forgotten even by friends, the “bulldozer”, wrote every day. He said there were still many literary projects. While the press finally remembered talking about Sulejmani, even calling him the “Albanian Balzac”, senior officials, as always, waited for him to die sadly to elevate his figure. “The soul of the great writer will always rest in the pantheon of knowledge of the Albanian nation”, declared among others the Albanian Prime Minister, Sali Berisha, on the day of the writer’s funeral. It’s weird! Why death often is expected to say a word of gratitude to people who deserve it? The dead do not hear. Then to whom do we say these always belated words? Why worry about being on time?

Myrteza Bajraktari, my neighbor, a student at the Faculty of History and Philology

Myrtezain, even though we were at the Faculty of History and Philology at the same time, I did not have the opportunity to know him as a student. I knew him as a neighbor. We lived just a few feet apart. He was the tenant to Shimi, a Tirana woman, who lived with her elderly mother-in-law and her three or four daughters. Her husband was a political prisoner, though he had never been involved in politics all his life! To make ends meet, Shimi, who worked as a cleaner in an eight-year school, rented out part of the house.

I became even more acquainted with Myrteza Bajraktar when fate threw us both in Brussels. Both of our wives knew each other. Myrteza’s wife, Kimetja, had previously been a violin teacher at the “Kongresi i Permetit” School of Music in Tirana. My wife, Desi, was also a solfeggio teacher at this school. I, in fact, had known Kimeten before. When I would start working as a journalist at Radio Tirana, Kimetja was a violinist in the symphony orchestra of this institution, so we worked in the same institution.

In Albania, all Albanians who came from Yugoslavia were called “Kosovars”. In fact Myrtezai was not from Kosovo. He came to Albania from the Albanian territories of Macedonia, if I am not mistaken, from Gostivar. In Macedonia he had spent 7 years in the country’s prisons, because he had never agreed with the brutal oppression and discrimination against Albanians in this republic and throughout Yugoslavia. He was accused of being a “great Albanian” and an agent of the Albanian Security! After fleeing Macedonia, Myrtezai came to Albania, convinced that suffering and hell were beyond the border, where Albanians in their lands and homes were foreigners, citizens of the last category, without any rights, without any protection. , negrit of the last colony in twentieth century Europe. He was soon disappointed. As soon as he crossed the border and entered Albania, he was sent to the Seman concentration camp in Fier.

More than two hundred and twenty Kosovars were serving an absurd administrative sentence in this camp. They were forced by the communist regime, as well as Myrtezai, to suffer for years, to become “heroes” of the drainage canals, simply because they had dared to cross the “border” and come to their beloved homeland, Albania. They were administratively convicted, as Myrtezai was convicted, for illegal violation of the state border of the Republic of Albania! In fact, the paranoid regime of Enver Hoxha, isolated them for years from the rest of the population of the country, which was ordered, meanwhile, to beware of Kosovar emigration, which if not completely, almost completely treated as a contingent good of the Yugoslav agency, UDB!

Only ten years after he arrived in Albania, Myrteza was given the right to study at the University of Tirana where he graduated in the Department of Albanian Language and Literature. Myrtezai himself remembers the first day of his studies with the same sad humor. He was relatively old in those years, having spent his youth in prisons and concentration camps. When he entered the auditorium, the other students standing in front of him stood up in respect. They had thought that not a late student had entered the hall, but their professor! After completing his studies, Myrtezai started working at the Institute of Linguistics, but it was not said that his life flowed normally, even insofar as it can be called such the daily life of the citizens of an authoritarian, dictatorial country.

Myrtezai wrote a letter to Enver Hoxha about the mistreatment of Kosovars

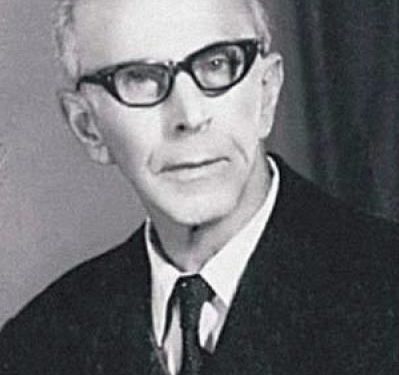

In a conversation I had here in Brussels with Myrtezai, he told me that he, seeing the injustices and mistreatment that was done in Kosovo to Kosovars as well as all Albanians who came from Macedonia, Montenegro and Presevo, had thought to wrote a letter to Enver Hoxha. He had also met Selman Riza, a prominent patriot and linguist from Kosovo, and had expressed his opinion. Myrtezai, pointing to me, laughed at his naivete. He thought then that Enver Hoxha was not aware, did not know the truth about the hostile reception and extreme mistreatment of hundreds of Kosovars in Albania. Selman Riza knew Enver Hoxha. They had worked together at the French Lyceum in Korça before the Second World War. He advised Myrtezai not to write his letter, because it was Enver Hoxha himself who had ordered this to be done with the Kosovar emigration to Albania, that Enver Hoxha was an unparalleled careerist, ready to kill everyone and sell everything.

Selman Riza told Myrteza that Enver Hoxha had invited him to join the Communist Party, telling him that now “it is time to make a career”. Professor Riza expelled him with the words «ik more shit»! These words, especially after he came to power, Enver Hoxha would never forget him, just as he would not forget everything he had done for Kosovo. Speaking about the life of Selman Riza, the researcher Behar Gjoka, said: “It may be a unique case in the world, in the East and in the West, and it is very bitter that within a period of 15 years, he has experienced imprisonment and internment by the fascists, the communists of Tirana after 1944, as well as the Yugoslavs, close ideological friends of the dictatorial power, which is established in the same year in Albania”.

I have known very little Professor Riza during the years when I was a student. I remember he was very “rebellious” about the time. I remember his response to the lightning bolts of some colleagues, who, by order from above, sought to crucify him. Actually, I do not remember much from this answer either, but I remember well the end of it, which ended with a “Ugh!”

Myrtezai’s arrest after the letter he sent to Enver!

Myrtezai did not listen to Professor Riza’s advice, he wrote his letter to Enver Hoxha. He did not send this letter to the dictator by ordinary mail. He gave it to a cousin of the dictator’s wife, Nexhmije Hoxha, a friend of his from Dibra with whom he had been an accomplice in Yugoslav prisons. He handed over the letter to Myrteza, the dictator himself. Professor Riza warned Myrtezai that if he wrote this letter, he would be arrested and so it happened.

Enver Hoxha was very interested in anonymous letters or fabricated as anonymous. He used these letters when he was interested in hitting both left and right, mercilessly, everything he saw as an obstacle to his rule. Dictator Hoxha was not at all interested in open, sincere letters written by honest people, patriots or even ordinary communists. These letters put him in an uncomfortable position. He was playing the card of ignorance of a reality or problem. Letters, like Myrteza’s, burned this card to him. Being paranoid, he also suspected that, through these letters, he was being provoked. The dictator could not allow himself to be provoked. That is why he, by fabricating the most absurd accusations, has severely condemned some of their perpetrators. The unconverted should have been considered lucky and thought that their letter had never reached Enver Hoxha, that they had hidden it from him. On the contrary, they too were met by the endless caravan of convicts of the dictatorship.

Myrtezai himself says that he did nothing, did not say a word against the regime or the dictator, he may have consulted someone else about the letter he intended to send him, but only that. That alone would be enough for someone to make the next denunciation and Myrtezai to be arrested and suffer, as in Yugoslavia, a few more years in prison. If I am not mistaken, in Macedonia he was imprisoned as an agent of the Albanian secret service, in Albania, the Albanian Security took care to spread to the public the version that he was an agent of the Yugoslav secret service, UDB. It was done, more or less, as well as with Professor Selman Riza. The communist regime of Tirana handed over to his Yugoslav allies and friends Professor Riza, who was wanted by them as a great Albanian “irredentist”. Professor Riza ended up in Yugoslav prisons. Then it would be official Tirana that would label this great patriot as an agent of the Yugoslavs!

State security forced a Kosovar to testify against Myrteza

Myrtezai was brought to trial by false witnesses, his friends, who had allegedly tortured him. One of them, a young poet of Kosovar origin, very talented, Albanian Security had prepared six typed pages, which he had to read in the courtroom. He began to read, but tears did not allow him to continue until the end. He was rushed out of the courtroom. His testimony became compromising to those who had commanded him. He was an unfortunate young man, without a job, without a home, who had tried to end his life. In this state he became a comfortable prey for State Security. In exchange for testifying about Myrtezain, he was provided with both a job and a home.

When the overthrow of communism in Albania began, Myrtezai found the opportunity to leave with his family, wife and three children, and sought political asylum in Switzerland. With the victory of democracy, he was appointed to work at the Albanian Embassy in Switzerland. He did not stay long in this post. He told me that one fine day, they had asked him from Tirana to spy on his colleagues. It was the same request made to him under the communist regimes in Yugoslavia and Albania. Then this kind of “service” was required in the name of communism, now in the name of democracy. The political system changed in Albania, but Myrtezai remained what he was. He never betrayed himself, his endless sacrifices and hardships, his years of imprisonment and exile. He refused to talk behind his back about his colleagues. All his life he had been pure and could not kick this life for any price, for any post or convenience. The consequences were not long in coming. He was thrown into the street. Being an employee of the Albanian Embassy, he had lost the status of political asylum in Switzerland, ie the right to stay in this country. Myrtezai returned to Albania to be unemployed, without any means of livelihood.

Now Myrtezai is a living collection of diseases, the hospital beds are as “familiar” with him as the bed of the small apartment where he lives here, near the Ijzer metro station in Brussels. There does not appear to be any hostage, grievance, or curse on his life, nor on those who crippled him. I have seen him from time to time in Albanian rallies. Completely gray, he speaks as the honorary president of this or that association, reading a letter, which shakes him tightly with his hands, which tremble. We rarely drink coffee together at the Metropol, in the center of Brussels. Again it is the hands that betray his Olympic calm. They hardly obey; they hardly own the cup of coffee. Myrtezai is not upset. He, always noble, laughs as if caught in guilt without wanting to blame the real culprits, those who being the real and fiercest enemies of the people and of Albania treated him as an enemy.

Among the “enemies of the people”, our classmate, Haxhi Tuçi

In addition to Myrteza, a few years after graduation, one of our classmates, Haxhi Tuçi, joined the ranks of “enemies”.

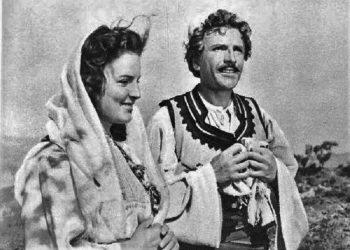

Haxhiu was one of the seven children of the couple Sabri and Maria Tuçi. Sabriu had graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts “Fidias” in Rome. In Italy he was acquainted and in love with Marie, whom I had the opportunity to meet once when some classmates paid a visit to Haxhiu’s house. Then she left me the impression of a beautiful and dignified woman, somewhat silent. I did not have the opportunity to meet Sabri. I knew him as one of the most famous Albanian sculptors of the time, I knew him through the works he had exhibited at the Art Gallery in Tirana or elsewhere.

In the late ’60s of the last century, the dictatorship arrested Haxhiu’s uncle and his mother Marien, who was accused of “agitation and propaganda” against the government and as an agent of Italian imperialism! This is where the tragedy of the Tuçi family begins. Sabriu does not raise his head until the day he died of pain.

Haxhiu was the first of the boys in the course to get married. Charming guy with athletic body, candid to naivety, quite sociable, he very quickly became a father, the first father of the course. His family was hit after Maria’s arrest. I happened to be near him once by chance on the street in Durrës Beach, during those years. He passed by and pretended not to see me, continued to leave quickly. This is how all the friends, benefactors and comrades behaved during the years of dictatorship, who did not want to endanger others even with a greeting, with a “how are you?”.

In the summer of 2010, I met in Tirana Shyqyri Vlashi, a former student of our History-Geography course. Shyqyriu was originally from a small town near Durrës, where Haxhiu lived. We had not seen each other for years. The thought is sometimes capricious. I do not know how, as soon as I saw Shyqyri, I remembered how in the first or second year of studies, Haxhiu wrote love letters to him. I remembered how much trouble these two letters caused them. I asked Shyqyri if he knew anything about Haxhi Tuçi, how he was, how his life had gone, what he was doing? “Haxhiu is dead,” he told me bluntly. He was probably the first of his classmates to die! He was too fragile, too sensitive. His body, his heart could not bear the weight of the pain for long.

In an interview given by his older sister Vojsava to the Albanian press in 2009, he says: “We children, after the death of our beloved father, after the advent of democracy, went to Italy, to Mama, who had suffered without cause and wanted to die in her birthplace.” Where is Haxhiu’s grave, next to his father, Sabri, in Durrës, Albania or near the grave of his mother Maries, in Italy? I do not know.

During my student years, I kept the same diary. I browsed it to see if Haxhiu was not “there”. I had a retrospective meeting with him. On August 22, 1964, I wrote in my diary: “After a few hours of exercise at night, you return to dinner, tired and very hungry. Put in front of a plate of «soup»…! Some of us could even eat a couple of tablespoons of that kind of dish. Someone of us threw an onion and divided it into six parts, I mean equal. In fact one piece was cut slightly larger than the others. Haxhiu intervenes and makes me give that piece, since I do not touch that kind of “dish” at all. Otherwise I would have to eat dry bread, while now… ”! These notes belong to the time when we, as students, did the 45-day military training in Korça, to prepare as reserve officers.

I also have two postcards from Haxhiu in my small archive, one from 1966 where he wishes me a Happy New Year and a “good start to my new job” and the other from 1968, through which he wishes me a Happy New Year again by added: “I also wish you to learn to read and write in order to make correspondence. I kiss you-Haxhiu”. We did not have the opportunity to correspond in subsequent years. Haxhiu was silent forever before his death! Memorie.al

The next issue follows