By Bashkim Trenova

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the war period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘People’s Voice’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances became acquainted with some of the ‘reactionary families’ and their sucklings, whom he described with a rare skill in a book of memoirs published in 2012, entitled’ Enemies of the people ‘and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

“Enemies of the people”

The troubles for Kristo Frashëri would not end with the War. For the regime, Kristo Frashëri had shown, not in one case that he was incorrigible, that he should be “re-educated”! He was removed from Tirana and taken to distant Përmet, in the southeast of Albania. There, for five years, he remained isolated from scientific life and contacts with his benevolent friends. Kristo Frashëri’s troubles are not over even today, as I am writing these lines, when he is 90 years old.

Professor Kristo Frashëri, a prominent patriot and a great rebel even in democracy

Prof. Frashëri has a scientific production that covers a period of 70 years. He has published research articles, historical papers, documentary volumes and scientific monographs, which deal with events, personalities and processes of the history of Albania. Despite his age, he still continues to make an active contribution in addressing many past or present problems. In my view he always remains an outstanding historian and a great patriot. He also remains an incorrigible “rebel” even in the years of democracy.

Following the interview given by Professor Kristo Frashëri in January 2010 on the TV show “Opinion” “Klan” I was glad to see him testify, regardless of age, an enviable strength and clarity of thought. His last words saddened me. Professor Frashëri closed the interview by saying that his eyesight was weakening. He still had plenty of projects, but needed someone to help him with his work. He lived alone. A woman who served him also paid with his pension. He could not share that small pension with anyone who could offer him an auxiliary service in his scientific work. The Academy of Sciences once paid someone for this purpose. Not currently. This means that objectively he has been deprived of the right to give his incomparable and irreplaceable contribution to Albanian historiography. This is because he is always himself, he speaks his language, he does not know how to do “big politics”, and he does not want to die as a mercenary.

Professor Frashëri has been honored with the title “Honor of the Nation” by the President of the Republic of Albania. This “Honor of the Nation” in the TV Klan show requires the least, to help not him personally, but Albanian science. At the end of the show, he even thinks that he did not exaggerate with his request and addresses the host of this show with the words: “If you want, these last words wait in the montage, do not transmit them”. One day when Professor Frashëri will leave us, surely, from the left and from the right, from scientific institutions and independent associations, they will hurry to show how great he was, how close they were to him they. In short, the hypocrisy ceremony will be repeated.

In our course we did not have any students with “biographical stains” or, as it was said, “Affected”. In fact, during the dictatorship, no member of what was known as “declassed families” had the right to pursue higher university studies. The students of the University of Tirana were chosen from among the families associated with the regime, communist families or families, who had not manifested any opposition, any dissatisfaction, however distant, towards the communist regime or Dictator Enver Hoxha.

My long bets that became a problem in college!

Although there were no enemy students or, more precisely with such backgrounds, declassed or shady in biography, the class war was not forgotten in the University, the “enemy” was not forgotten because, as the Party said: “The most dangerous enemy is the one who is forgotten”. Thus in the University, the “enemy” was defeated by fighting what were called “foreign bourgeois performances”, “foreign micro-bourgeois psychology”, “decadent fashion and tastes”, “influences of Western art and culture”, etc. of this nature. I remember the professor of psychology, Thoma Miçolliu, a round man, short, with his hair combed aside, Hitler style. I was in my first or second year of college. I liked to carry long basses. I kept them this way without even thinking about the bourgeoisie or the proletariat, without asking at all whether this was how I reflected a bourgeois or proletarian psychology. The Party and Thoma Miçolliu did not think so. He was one of the most active communists of the Faculty.

Even my bets had not escaped Micolli’s vigilance. Several times in the lecture hall he addressed me, as if with a laugh, with the request to wait for them. I passed his requests with a laugh. This “verbal battle” continued until the threshold of the exam season. Before taking the psychology exam, Professor Miçolliu addressed me, again in the lecture hall, in front of the students of some courses with the words: “Will you cut those basets, or do you want to cut yourself in the exam”. I had to choose between exam and bets; I chose to cut the bets.

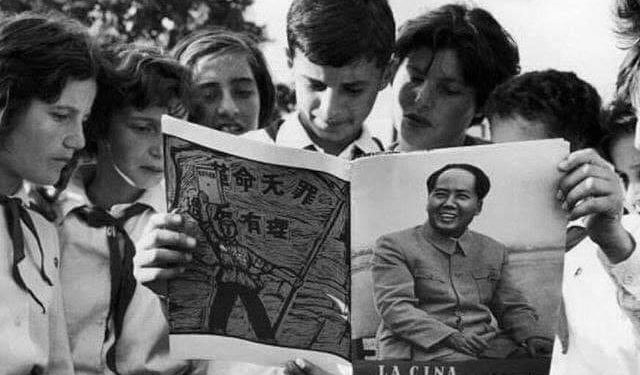

30 Chinese students at the Faculty of History and Philology in Tirana

I started my studies at the Faculty of History and Philology of the University of Tirana almost immediately after the severance of diplomatic relations between Albania and the Soviet Union. In search of allies, Albania’s communist leadership linked the country to Mao Zedong’s China. She swore in front of the Great Wall of China for an “eternal and unbreakable Albanian-Chinese friendship”. “Eternity” did not last more than 15-16 years and was broken like a clay vase, as if it had never existed. Meanwhile, during the years of the “great Tirana-Beijing friendship”, the influence of the thought and practice of Chinese communism was felt in Albania, Albania began to be Chine seized, to see with suspicion, even with hostility, everything Western or seen interpreted as western.

Mao Zedong’s China was imitated in the most servile way in Albania of those years. Bassets or long hair of Albanian youth, pants that ended up less than 18 centimeters and more than 22 centimeters, wide or wide belts, mustaches and beards, everything was under surveillance, under severe criticism and threat of the Labor Party. It was “forgotten” that we were two peoples, two countries, that we could be allies and friends, but that we were separated by thousands and thousands of kilometers of geographical distance, we had completely different histories, psychology and way of life and thought, which were also completely different , often even incomprehensible. It was impossible to implant a small China in Albania.

At this time, 20 or 30 Chinese students were studying Albanian language and literature at our Faculty. They were quite correct and modest, disciplined like a small military unit. Many of them also attended our course to listen to Professor Kristaq Priest’s lectures on the History of China. They also took part in the actions that we did in the summer for the opening of new forest roads, as in Prat of Peshkopi, or for the construction of terraces for the cultivation of citrus, as in Jonufër of Vlora. I had friendship with their chairman, who was called Fan Jun Nan. Chinese students said he had been a professor of classical literature at Shanghai University. Fan Jun Nan had also come, officially, to learn the Albanian language, but rarely attended language lessons. It was said that the reason for the absences in lectures was his poor health. His friendship with him also brought me closer to other Chinese students, who did nothing without his prior approval.

Chinese students at my sister’s wedding and toasts for Maon and Enver

From my childhood, at the age of 10-11, I was intrigued by Chinese students. I met them during the summer holidays on the beach of Durrës. There were four or five students. They were the first Chinese to come to learn the Albanian language. One was sent back to China without finishing his studies. As his friends explained to me, he had shown signs of pessimism about the future. This was also the reason for his return to his homeland. I continued to meet with others in Tirana, after the holidays. Albanian teachers had advised them to socialize with children, as their language is cleaner and easier to understand. I also invited two of them to my sister’s wedding. They were interested in getting acquainted with an Albanian wedding ceremony. I made the same invitation about 10 years later when my brother, Genci, also married Fan Jun Nan and another Chinese student named Mao. I remember bringing as a gift two portraits of Mao Zedong and a pair of beads for his brother’s wife, Xhar. At her sister’s wedding, Mao Zedong was absent. When my brother got married, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution had begun in China. That’s why, I think, the beads were also associated with the two portraits of Mao Zedong. In fact Mao was present everywhere in China, but also in our relationships with Chinese students.

I remember one evening in the student dormitories. Together with a classmate, Mehmet Kotheria, we were drinking from a glass of brandy. At one point a Chinese student knocks on the door. He asked us not to make noise because the others were sleeping. We pulled him by the arms and put him in the room where we were “celebrating”. We also offered him a glass of brandy. He refused to drink. Then we raised the glass for Chairman Mao’s health. What to do? Whether he wanted to or not, he could not refuse. Then we raised a toast for Comrade Enver Hoxha. He could not help but drink a toast to Comrade Enver, as we had drunk for Maon. Then we set up another one for our two glorious leaders, then one for the great Albanian-Chinese friendship, etc., etc., until we escorted him holding him by the arms in his room. Thankfully he slept in a room with only one Albanian student. For him, it was not a problem a glass turned upside down or a few glasses turned upside down.

Comparing the first Chinese students, who came to Albania in 1955 with those I knew in my University years, I have the impression that the latter were more politicized, more restrained in their conversations, more schematic. In this small space of time, communist ideology and practice had done their job. This was observed everywhere even though it was “justified” by the nature of the Chinese as a people.

In the lodge of the Opera House, close to the diplomat of the French embassy!

During my high school and university years, I often went to the Tirana Opera and Ballet Theater. One evening, in mid-September 1964, I decided to go see Bizet’s “Pearl Fishermen.” As I was heading to buy a ticket at the counter, I was approached by a blond man, about 25 years old, tall and with a sporty body. He immediately seemed to be a stranger. He offered me a ticket. I wanted to pay him, but he refused. I insisted, although the ticket he offered me cost 50 lekë, while I wanted to buy a ticket to the gallery that cost 20 lekë. He again refused. He asked me if I spoke Russian. After receiving my affirmation, he continued to speak to me in Russian. He told me he was expecting a friend, but since he did not come, he was giving me his ticket.

In the hall I sat next to him leaving an empty seat between us. He asked me to move and sit next to him, to occupy the empty space that separated us. “I said, ‘I want to talk to people, but as soon as I greet them, they leave.’ Aren’t they afraid”?! To show him that he had no reason to think so, I moved and sat in the empty space that separated us. He introduced me as Robert Bonneau. He told me that he was a translator at the French Embassy. He stressed that he was not a diplomat. I happened to be in an awkward position. I knew I could not stand next to a foreigner, much less to an employee of a Western embassy, who in the logic of the regime was definitely a secret service agent. At that time in Albania there were only two embassies of western countries; French and Italian embassies. The movements of the employees of these, as well as of other embassies, were controlled and under surveillance. I did not want to have trouble with the State Security, but I also did not want to tell this diplomat that in Albania people were afraid of an accidental contact with a foreigner.

I followed Bizet’s opera “Pearl Fishermen” like a thorn in the side. During the break, between the two acts, we talked about the show, the artists, the stage performance, the voices of the singers, etc. We were both satisfied; we had more or less the same appreciation. At least, that’s how it seemed to me, judging by Mr. Bonneau. He probably even expressed himself differently than crazy, just to be polite. At the end of the show, I hurried to part with him. Before saying “good night”, the Frenchman told me that he would like to meet with me again if I was free. He told me that he wanted to learn Albanian and asked me if I could help him? To avoid the answer, I asked him, “When are you free?” Mr. Bonneau told me he was always free. I frowned, not knowing what to say. I hastened to whisper that I, indeed, was quite busy with my studies, and that, surely, we would meet again at the Opera House. For Robert Bonneau, this was the answer to the question he had asked me from the beginning: “Why are Albanians afraid to talk to me”?! I was scared and he could not help but understand this. Moreover, I was not the only one. I was probably the only one who had dared to do so.

My refusal to meet again with the French diplomat!

The French translator or diplomat, Robert Bonneau, before we parted, also gave me the phone number of his office at the French Embassy in Tirana. He also invited me to see a concert of a French pianist that was coming soon to Tirana. I went and saw the concert. The French pianist was the first and last Western artist to come to present a spectacle at the Opera House in Albania, during the communist dictatorship. As I watched the pianist play, which amazed me with his virtuosity, I was always worried when I thought that suddenly, a State Security officer might stop me on the street and ask me to accompany him, I do not know where, just for some random questions…! Thankfully that did not happen.

I later found out why I had escaped the usual “procedure”. Mr. Robert Bonneau, had not stayed long in Albania after the concert given by the French pianist at the Opera House. From Tamara, a handsome redhead student of the English course, I learned by chance later that he had left to perform military service. She had this information from a classmate who, as it was then spoken among the students, was a Security officer. Even his name was, coincidentally, Robert.

I have seen Mr. Bonneau on another occasion, but not far away. This happened during a visit made by the then Chinese Prime Minister Chu En Lai to Tirana. We, the students of the Faculty of History and Philology, had taken us out on the streets to welcome the distinguished friend from China. We were placed on the sidewalk in front of the French Embassy. While waiting for Chu En Lain, I saw that on the lower wall of the Embassy, Robert Bonneau was sitting and waiting. He believes he did not notice me. I, of course, neither greeted him nor spoke to him. Even so, I had crossed the line.

Security, as I believe, is not that it has tolerated or “fired” the case. Our vigilant eye could not escape our meeting and conversation at the Opera House. He just did not want to act immediately, but to create some space to see if there would be a second or third meeting. The reception burned the cards because, in the meantime, as I said, Robert Bonneau left Albania. So I believe the file was closed before it was opened. Anyway, I got lucky. When I told this “story” to my brother, Genc, he told me: “You had so much, they will catch you”!

With Chinese students at the Madame Butterfly Opera House

The meeting with the French diplomat at the Opera House reminded me as I was writing these lines about Chinese students in Tirana. I once invited Fan Jun Nan and another Chinese student to see Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly. I chose this thinking that the events were taking place in Japan, an Asian country that had to have a lot in common with China. At the end of the show, I asked the Chinese if they were crazy, what their impression was. They told me they did not like Puccini’s opera. They disagreed with the treatment of the role of Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton, a US Navy lieutenant, one of the main characters. According to them, Pinkerton’s return to Japan to look for his son presented him as human. According to them, this character should be seen not as a man, but as a representative of American imperialism, which seeks to rule the world through wars and aggressions! We in Albania also described what we knew as American imperialism, as an international gendarme of the peoples and their freedom. We, however, never made any parallel, which would seem absurd, between the hegemonic ambitions of this imperialism in the twentieth century and the characters of an operatic piece first staged in 1863.

I once again called two Chinese students to see a historical film about the emperor of ancient Rome, Caesar. They did not like this either because, according to them, Caesar was glorified while he had been an emperor, conqueror. Failed in the first two cases, I thought I would please my friends by inviting them to the performance of a Chinese play, which was staged by the Durrës Theater. I did not succeed here either. For Chinese students, the way the part was staged, the actors’ play, made it European, so that it had nothing Chinese. It happened that a few months later, the same play that was played by the Durrës Theater, appeared in the city cinemas. The Chinese had made it as a movie. It was the turn of Chinese students to invite me to see the film. We went and in the end they asked me crazy church for the movie? I told them that I liked more the performance on stage by the Durrës Theater. For them it was the opposite.

With the onset of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, all Chinese students returned to China. Before leaving I invited two of them to dinner at my house. I was told that they had received permission from the Chinese Embassy to come to me. I do not know how their fate went. After a long time, in the early ’90s of the last century, I met one of the Chinese students who had studied in Albania. He was appointed Chinese ambassador to Tirana. One day he held a banquet for the representatives of the Albanian press. We stayed close and talked, remembering the past, the student years. I asked him about some of the Chinese students and he repeated to me the same answer in each case: “he is dead.” I suspected his non-answers were a Chinese-style formula, to say he did not want or could not talk about them. And, if so, it means that they did not have it easy with the Great Chinese Proletarian Cultural Revolution, that any or some of them were “affected” by this supposed revolution! However, these are mere conjectures. Memorie.al

The next issue follows