Taisa Batkina Pisha

Part twenty-six

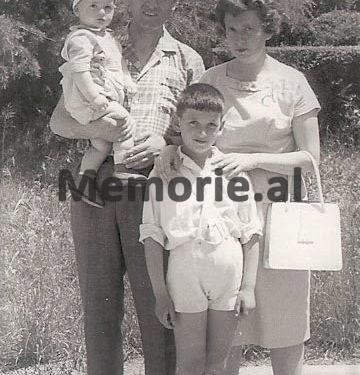

Memorie.al/ publishes the unknown story of the Russian Taisa Batkina (Pine), originally from Tula, Russia, the third child of a very poor rural family, who was left an orphan at a very young age, after her father lost her life while working in one of the coal galleries on the outskirts of Tula, where he worked as a miner, (shortly after escaping arrest, accused of “supporting the enemies of the people”) and she grew up with difficulty great economic, as their city continued to be under the bombardment of German forces, which had reached as far as near Kursk. Taisa graduated from the Faculty of Chemistry, near the ‘Lomonosov’ University of Moscow, where she met and married the Albanian student, Gaqo Pisha, originally from the city of Korça, who at that time was studying at the Faculty of Philosophy in Moscow and both together in 1957, they returned to Albania, together with their newborn son, Sasha, and began life in the city of Tirana, where Taisa was appointed as a professor of Chemistry at the State University of Tirana, while Gaqo, in the chair of Marxism- where they worked until 1976, when the State Security arrested Taisa Batkina on fabricated charges, accusing her of being a “Soviet KGB agent” and sentencing her to 16 years in political prison, which she suffered in the “Women’s Prison” in the city “Stalin”, from where she was released in 1986, while her husband, Gaqo Pisha, had died in 1983, from a serious illness. The tragic story of Taisa Batkina (Pine), in the inhuman camps and prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, where she spent a decade of her life, along with many compatriots from the former Soviet Union, or other Eastern European countries, comes through her memories, published in a book entitled “We hoped and survived”, memories which, her son, Aleksandër Pisha, kindly offered her for publication, in Memorie.al

We hoped and survived

I dedicate it to the bright memory of my husband, GAQO PISHA

This is a book of memories. In it I want to tell about my life and the lives of my friends, Soviet women, who tried prison for several years just because they got the courage and got married and linked their fate with that of Albanian students. The prison was part of the great GULAG in the small Balkan country, Albania, where for many years the bloody communist regime of Enver Hoxha ruled, who was a loyal student of Stalin and a follower of his cause.

Through this book I would like everyone to learn about the inhuman trials we experienced and the horrible years we spent in Albanian prisons, just because we… fell in love! And let no one ever forgets what totalitarianism, despotism is and what the consequences of this system are.

Continued from the previous issue

Silvana

After a while she said to herself, that the brother would not get better. Thus passed the years of imprisonment for the beautiful and so good Silvana. She was close to 7 years old and was released with us after the amnesty of 1986. I do not know anything about Silvana, she went to Kukës, I fled Albania. They say he went to Australia.

Two Bedrijet

So far I have written only about very good and very unfortunate Albanian women. But there were others in the camp, to poison life, create an unbearable atmosphere. I do not like to write about them, but I am mentioning the most prominent ones. When they brought us to the camp, we were greeted by our friends, who had come here before us and were already somewhat accustomed and adapted. They told us about life in the camp, about the conditions, who we should stay away from, who we should be afraid of. Among many others, the two Bedriets stood out. Bedrije Ashiku, a tall, gray woman, with remnants of former beauty, but with a wicked face, cunning of a skier. He was from the northern city of Shkodra, but he had nothing in common with the mountain villagers, loving and kind, surprisingly clean. She was intriguing and a born spy. The accusation against him was: “attempt to cross the border”. Once she was the wife of a police personality, there was a boy who allegedly fled to America. It was hard to tell at her where the truth was and where the lie was. In the camp she was widely used as a provocateur, as a fifth column, or as a false witness. She performed all these tasks brilliantly, but she also spied. No wonder no one loved him, we avoided them all. Bedrija constantly tried to remove herself as a noble lady, aristocrat.

For the first acquaintance with Bedrije, very funny, with the humor that distinguished her, Ina Shahe told: “They took us to the camp, where near the door stood an old, tall woman, who addressed us in French. O God, – I thought, – where have we come like this… here, at the door, to speak French, but what will happen next”?! There was nothing further; Bedrija did not know any other French words”! She tried to gain our trust, to enter our room by any means. One of our friends, Bedria, stole something, then, when the quarrel broke out; he found it among his belongings. He considered that he had every right to enter our room at any time. We had to show him the door. In fact, we were a convenient object, many trying to “earn points” by spying on us. To avoid reports, we tried to stay away from Bedrija and people like her. Her petitions and provocations were so low and filthy that I feel dirty when I remember them. The elders told us that when it was forbidden to sew and hold a needle in the camp, she would secretly put a needle in someone and immediately rush to report it. They immediately checked, found the needle and put the poor victim in the dungeon. When Bedrije Ashiku served his entire sentence, without benefiting from any reduction, although he had shown so much diligence and, at last, left the camp, we rejoiced immeasurably. Now we had one less Bedrije.

But there was still a Bedrije, Bedrije Havale!

She was a rude, rude, scandalous woman, she looked more like an ordinary prisoner than a political prisoner, but she was with us, in our corps, because she was tried under a political article. All his life he was involved in all sorts of scandals, quarrels, beatings, and espionage, outside and in prison. Before we knew him, Bedrija had served several prison sentences and several internments. When he was out, Bedrija wrote reports to the neighbors. He liked this job; he had been dealing with it all his life. He spoke in meetings, cursed the government, the party leaders and put him in jail. Once out of there, everything started from scratch. To annoy the neighbors, he kept a herd of dogs and cats at home. (Not to take revenge, Bedrija took care of the animals). The year he was last arrested, he kept almost twenty dogs in the yard, which did not allow the neighbors to sleep peacefully or walk freely on the streets, because they had several times attacked passers-by. Neither the prayers nor the orders efekt had any effect and Bedrije and his whole family was interned in a remote village. But in the village he had to work in the fields, no one would give him free bread; neither Bedrija, nor her husband, nor their son, were accustomed to such work. Living conditions in Albanian villages have been very difficult. And Bedrija set himself the goal of in entering prison. There you were provided with a piece of bread and a bowl of lentils; can shave by blackmailing and stealing.

She started giving speeches in front of the villagers, throwing slogans, cursing the government, the party. The villagers reported him and, finally, Bedrije was forced to let him in. She had no convictions; she just had to escape exile. She was not an opponent of the party, of the government, on the contrary, every time the opportunity arose she swore love for “the party and comrade Enver”…! Simply, the intriguing character, the malicious nature did not leave him alone. What did Bedrija not do in our corps! She was not fired, she did not work alone, and she did not let others work. In the morning, when the young and powerful women were at work, Bedrija would frighten the old men, take their food and firewood. It was only after they had treated him well and threatened to make him dead that he left some alone. During the repeated sentences, Bedrija mastered the rules and regulations of the prison. He knew exactly what was allowed and what was forbidden in the camp and wrote reports against the command. If you search, you will always find a slight deviation from the rule. Bedrija noticed everything, wrote to her and immediately started reporting. I remember when I was working as a pig care assistant, a dossier had to be hatched and, to protect the litter, and the caretaker was taken out of the camp gate, accompanied by guards. But, as a rule, after dark, all the prisoners had to be behind the barbed wire and Bedrija immediately started the report up. The caretaker of the pigs was no longer taken out of the camp, the pigs died. In our political part of the camp, a heavy atmosphere was created. Every day scandals, beatings, quarrel broke out and always at the epicenter would be Bedrije Havale, who terrorized the entire corps. We asked the command to take action; our director, who knew Bedrije well, punished him, put him in jail and we had fun. We were counting the days until she was released. But even in the dungeon, Bedrija did not give up, cursed again and again, asked for a meeting with the director and again made a scandal. The work ended with her other arrest, and then she was retried and added another three years. She tried to get in between us too, but got an answer, which made her forget the way to our room and avoid us. We stood together and defended each other.

There were also many other women, young, strong, who did not lack Bedrija. Finally the prison directorate lost its temper; Bedrije was removed from us and taken to the ordinary. We breathed a sigh of relief. And Bedrija got what he deserved. Ordinary people knew him well, they had been with him in prison before, and they had known him outside. After the first fight, Bedrije was beaten peacefully, so much so that her whole face looked like a big blue stain. We followed him behind the fence, how he was beaten and no one had any mercy, we even rejoiced that someone was taking revenge on us as well. Bedria complained in writing to the ministry, to the prosecutor’s office, asking to be returned to the political prisoners, but they did not listen to him and for some time we remained calm, but afraid that they would not bring him back to us and the quarrels would start from para. Bedrije was returned to the political prisoners after the change of leadership of the camp. She went on with the old ones again, but was significantly wise. The ordinances taught her a good lesson and she seemed to lower her head. Just then, when we were afraid that Bedrije would be returned to us, a tragic political event took place and the way we found out was something to laugh about. It was December 1981; we were sitting in the canteen and watching the latest news on TV. This was a mandatory activity, and then everyone could do their own thing. Suddenly Arziko, a prisoner, former party employee, the command trustee, who had just been called urgently, returned to the canteen. She looked alarmed. “Do not play anyone from the country! You will not go to the corps”! She ordered. Qerimja, who was sitting next to me, addressed her friend, Nadja: “What happened? They will surely bring Bedrije back to us here”! And he blushed in fear. It seemed to us that there was no savagery more frightening than Bedrija… but the events were of a completely different character.

Announcement of the death of the Prime Minister, Mehmet Shehu

We sat, we waited. The TV was turned on again. These were the last news of the evening, at 10 o’clock. An announcement was being made by the Central Committee of the Party and the Council of Ministers about the suicide of Mehmet Shehu, Enver Hoxha’s collaborator and closest friend, Prime Minister. The announcement was heard in uneasy silence. Qerimja started to cry with cries, as is customary in Albania. “Shut up! – Nadja stopped in a low voice, – how do you know that you should cry? Maybe it is the opposite”! Qerim was silent, we also did not speak, we were silent and we were thinking, what is this? In that period, when Enver annihilated the entire leadership of the party and the state, this suicide could not have been accidental. But was it really suicide? What did this mean, the end of the persecution, or its intensification? We did not have any information. We only knew that Mehmet Shehu had been the most loyal and closest collaborator of Enver Hoxha, a savage, bloodthirsty man…! For a long time he had been Minister of Internal Affairs. In Albania they were afraid of him. He often went to enterprises, institutions, schools. Often, after his visits, directors, engineers were fired.

My meeting with Mehmet Shehu at the University!

He once came to our faculty, in 1962, immediately after the breakdown of relations with the Soviet Union. Then I taught Chemistry at the University of Tirana. He went into the lab, asked me some standard questions. I answered simply. Someone told him I was Soviet. He addressed me in Russian (he had graduated from the military academy in the Soviet Union). “Soviet?! Get letters from home”? – I came back. “Yes,” I replied. “And what do they write to you?” That we are dogmatic, traitors”? (I was shaking all over; you could expect anything from him.) “No,” I replied, “they do not write about politics, only about housework.” Mehmet turned around and left. I should have turned yellow in the face. To calm me down somewhat, the students started making jokes, laughing. From that short conversation with Mehmet Shehu, something weighed on my soul…! Now we have suicides! Wonder! The next day a short obituary was published in the newspapers with a small photograph in the middle. And a few months later, Mehmet Shehu was declared the fiercest enemy, a police agent, an Anglo-American-Soviet-Yugoslav spy, and I don’t know who else. Shortly afterwards his eldest son and wife were killed, the other two boys arrested… in a word, even with doing, as he had done with others throughout his life.

Lili Mitrovica

After the fall of the communist regime documents were published proving that this had been sanctioned murder, all the executors and witnesses of the case were liquidated. A copy of the scenarios that were developed in the Soviet Union in the time of Stalin. Among the prisoners was another category, that of intellectual women. There were teachers, accountants, clerks among them. The usual charge against them was agitation and propaganda, the terms of the sentence, 5 to 8 years. They were imprisoned because their fathers, husbands or sons had been in prison or had been shot. Together with us, the wife and daughter of the Chief of General Staff of the Army, Petrit Dume, who was shot in the 1970s along with the military elite, served their sentences. Following the arrest of Petrit Duma, his entire family, as well as the families of his brothers and sisters, was interned, and then part of the family was imprisoned. Or Lili Mitrovica. She was the daughter of Qazim Mitrovica, one of the main commanders of military units in Kosovo, who had fought against the Yugoslav communists led by Tito. Throughout her life she suffered from a father she had never seen. He was born after his death. During a period of “release of the spring”, which happened from time to time in Albania, she had finished pedagogical school, but was not allowed to work as a teacher, she could only work in construction. Smart, beautiful, tall girl… she could not start a family.

In Albania, it was difficult to find a man who did not want to know what the government thought of such girls. Qazim Mitrovica’s daughter was undoubtedly an enemy, even a potential enemy of the security services. We became friends together at camp. She understood things, was well versed in prison affairs, and often helped us to understand the messy relationships in our corps, especially in the beginning, when we had just arrived at the camp. From her you can always expect a wise advice. I was very happy when she was released, but I would miss her support and advice. When I got out of prison, I looked for Lily. She was still working in construction; they did not give her another job. After the fall of Enver Hoxha’s regime, she headed the women’s section of the Committee of Former Political Convicts and had the opportunity to help many accomplices. We were also friends with Nina. She was from Durrës, with a technical profession in construction. He had a Russian mother and spoke Russian fluently. She was put in jail only because her boss was arrested. It seems to me that they wanted to sue her for sabotage, but they did not find anything suitable for Nina and she “escaped” only with agitation and propaganda. I do not remember exactly, it seems to me that sometime in the late ’70s, Tefta Tasin was brought to the camp. She was the daughter of a Democratic patriot who had fought against King Zog’s regime in the 1920s. Her father had been part of Fan Noli’s democratic government, which Ahmet Zogu overthrew with the help of the Yugoslavs. Tefta’s father was injured and immigrated to Greece with his family. After the fall of the 147th monarchy in 1939, the family returned to Albania. Tefta’s father became a member of the Albanian government, which was formed in those years. In 1944, after the communists came to power he was declared an enemy of the people, was arrested and died in prison.

His whole family, his wife, daughter and two sons, people with school and culture, were also considered enemies of the people and spent years in prisons and internments. The government was afraid of such people, they knew a lot about the political struggle in the country during the period of coming to power of the communists and Enver Hoxha. At the Tefta camp, he initially sought to be treated as a political prisoner. He demanded that we be isolated from ordinary prisoners, that television be brought to our sector, and that he refuses to watch television in the ordinary canteen, as was the practice until then. She was very independent, worked selflessly, and never lowered herself, arousing the respect of some and the resentment of others. She rightly called herself and her family ideological opponents of power, while the guards and prison guards considered them enemies, violating the basic rights of the people. After the fall of Enver Hoxha’s regime, Tefta’s 88-year-old mother, Aleksandra Tasi, wrote and published a poem, which briefly describes the life of Enver Hoxha, the man who came to power over the blood of relatives, friends, comrades… man, whose whole life was filled with crime and betrayal. With these verses I want to close my memories as well. /Memorie.al