Dashnor Kaloçi

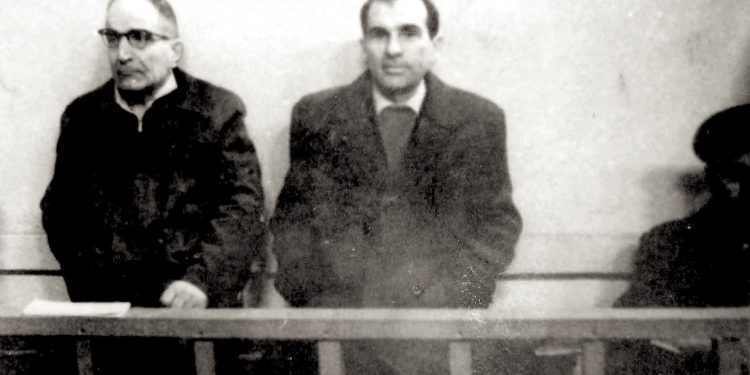

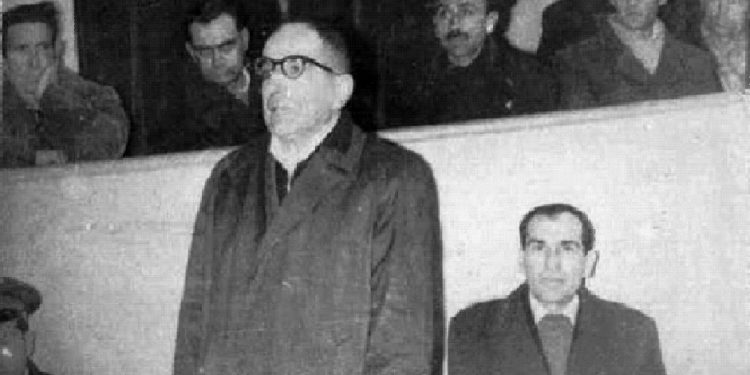

Memorie.al publishes the unknown memories of the intellectual Uran Kalakulla, former political prisoner, who suffered for more than 21 years, in the camps and prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, after in 1961, he was arrested, being accused that together with a group, which also included Pjetër Arbnori and Tanush Kaso, had wanted to form a group with a European social-democratic tendency, where as a result, he was sentenced to 22 years in prison, which he suffered mainly in Burrel prison, from where he was released in 1992 and interned in the village of Kryevidh in Kavaja, until 1988. Unknown memories of Mr. Kalakulla, author of several books such as “Verses in Handcuffs”, political essay “Albanianism and its Europeanist tendency”, monograph “Arshi Pipa, man, life” and works, as well as the autobiographical book “Twenty-one years of communist imprisonment”, of written after the 1990s, where he describes in detail some of the Catholic, Muslim and Orthodox clergymen he had as accomplices during his time in the communist regime’s camps and prisons, such as: Father Konrad Gjolajn , Dom Nikolë Mazrekun, Father Gegë Lumën, Dom Ndoc Nikajn, Dom Simon Jubanin, etc.

The well-known intellectual Uran Kalakula, who suffered for more than 21 years in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist dictatorship, in his memoirs written both during his sentence and after his release from prison, devoted a special place to him. Catholic, Orthodox and Muslim clerics, who throughout the period of the communist regime, were massacred in the most barbaric way by the ruling regime. Regarding the stoic attitude of these clerics in communist prisons, there was also this article which we have taken from the memoirs of Mr. Kalakula, published in his book “Twenty-one years of communist imprisonment”, which was published in 2001, shortly after he had passed away.

-Memories of the former political prisoner, Uran Kalakulla-

Why was religion banned by the communists?

“Everyone knows that, in addition to the intellectuals (as the brains of the nation), the communist dictatorship furiously persecuted the clergy, these representatives of spiritual education. Thus, by beheading these people, the body of the people remained without direction and then it was the Party that which would lead to the cursed path, the path of the devil. By overthrowing the king and God by force, the place of both would be taken by the “horned leader.” Everyone knows that communism, at its ideological roots was materialistic, so atheist.

Theoretically, he did not accept the “One”, whether this God or king, in the small material world. Did not the first verses of Marx’s First International begin with the denial of every leader, beginning with God and ending with the heroes, and that “liberation” would be won by the united proletarians themselves? United but without grass? Who would print them? The Party would print them! So, no cult for any leader, of any kind, but a “Steering Headquarters” named Party. Thus, the “unity” was avoided and the notion of a collective leadership came to the fore.

At first glance, this notion seems really democratic, popular, rational. But really under communism, or rather in “real socialism”, that is, in the theory of my whole life, since “I fell in my mind”, as a popular Albanian expression says, I have learned to worship the coryphaeus of knowledge and art. I am also accustomed to honoring such great figures of world-renowned leaders as a Pericles Athenian, a Cato, a Cicero, a Cincinnati, a Jefferson or a Kennedy, a Whiston Churchill or an Erhard Audenahuer, a Gand or a De Gasper and Sandro Pertini, as well as others in the field of democracy and humanity.

While in the national plan: a Skanderbeg, an Ismail Qemal, a Fan Nol and an Ahmet Zog and in the religious plan, where often the practice of religion was harmonized so beautifully with the national and cultural activity: a Pope Vojtila, a Gjergj Fishtë, a Shtjefën Gjeçov, a Ndre Mjedë, Vincens Prenush, again Fan Nol, father Kisi and father Ireneu, a Hafiz Ali Korça and others of this caliber. And, religiously, (since birth), it’s my turn to be a Muslim (even though no one has asked me about the religion I had to choose!), For the Albanian clergy, especially those of the Franciscan order, I have always had a major consideration .

As a rule, they never separated religion from the Homeland and laid the foundations of our national culture from the beginning. Suffice it to mention here Buzuku, Bardhi, Veriboba, Budin, Bardhi, Bogdan, etc. It was this foundation of tradition that was first demolished by Hoxha’s communists. And this was a centuries-old crime!

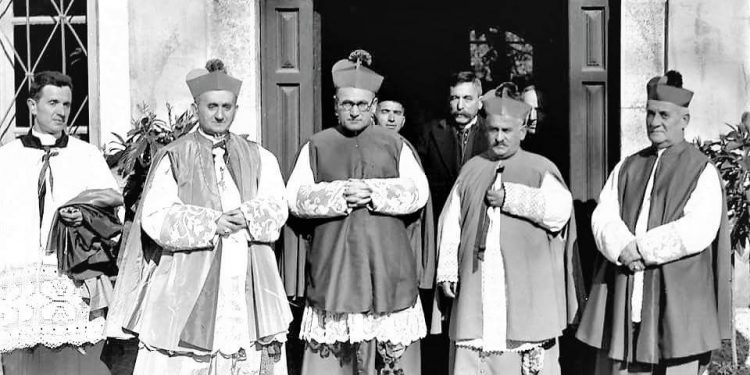

With Dom Nikoll Mazrrekun

I, for the time I spent in prison, had neither the opportunity nor the fortune to personally know such bright figures as: Father Bernardin Palajn, Dom Nikolë Gazulin, Dom Lazër Shantojën, Father Gjon Shllaku, Father Pjetër Mëshkallën, Dom Vinçens Prenushin and their worthy companions like these. But, I have known Catholic clergy, such as: Father Konrad Gjolajn, Dom Nikolë Mazreku, Father Gegë Lumën, Dom Ndoc Nikajn, Dom Simon Jubani and others. The bloody sickle of the red dictatorship had already carried out his macabre work on the first coryphaeus of the Catholic Church.

We remember her Father Visarion Xhuvani, Father Ireneu, Father Kisin of the Orthodox Church, or Hafiz Ali Korça, Hafiz Dërguti, Hafiz Ali Tarin, etc., Islamic clerics. I met Father Konrad Gjolaj in the Elbasan prison camp around 1967-’68. He was a man of average height, with a regular face, with an always serious attitude, generally somewhat gloomy, always silent, and who preferred to stay alone. I had with him only a polite greeting, nothing more. And so I did not approach him (nor did he approach me), wanting to respect his desire for voluntary isolation.

But his attitude impressed me, especially his grim face, where it seemed clear both a deep despair and a great disappointment. On the contrary, with Dom Nikolle Mazrreku I was somewhat closer, not too strong, because he also preferred retreat in itself. I met him in Burrell Prison, and for a while we even shot in a room (in my last years in prison), even against each other. All day long, he worshiped his own books and manuscripts, as I usually did. Each in his own work.

By then he had just finished the voluminous novel about Skanderbeg (which he did not let me read), as well as a novel with a bucolic character. He gave me the latter and I expressed my opinion after he asked me. But Dom Nikolla was more open to society than Father Konrad. He even knew how to make jokes, often with a very subtle irony (especially) towards the reality where we were, with some of his typical nipples and so. I had to admit, that I had respect for him. It was his second or third prison, amid ongoing internments.

He was a man who aimed from a height, body tied and with strong hands manual labor, as in exile he had practiced, to live, several types of crafts in the field of construction. He seemed to be a man of iron will and courage. But what made me respect this man the most was the fact that he had given a well-deserved answer, through a pamphlet published before World War II, to an Italian Catholic missionary dressed as a priest, with the surname Cardigan, who had worked in Albania for many years and therefore had learned Albanian very well, as he had made one or two Italian-Albanian dictionaries and vice versa, which were valuable in the field of Albanian lexicography.

But when he went to Italy, he published a book or a pamphlet in which he spoke very badly about our country. He had gone so far as to present the Albanians as people with tails, thus violating the bread of the hospitable Albanian table, which he had not lacked wherever he had wandered around Albania. Thus, the patriotic boy, Nikolle Mazrreku (I do not know if he was still a seminarian or was ordained a priest), with his pamphlet pamphlet, had worked a hundred times for this masked foreign baker! I even heard that this pamphlet was in the hands of the first patriotic demonstrators against the fascist Italian occupation of our country, between 1939-1940.

Who was Father Gegë Luma?

In Burrel Prison I met Father Gegë Luma. I say that he would be from Dukagjini and had become a priest in his own province, living like this, almost all his life, between the mountains and the inhabitants of that area. Consequently, he knew at his fingertips the Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini, in all its details, so much so that he was able to quote you article by article, paragraph by paragraph, this old monument of the right of our mountains and, why not, even of civic life for a long time, especially in the part of Gegëria.

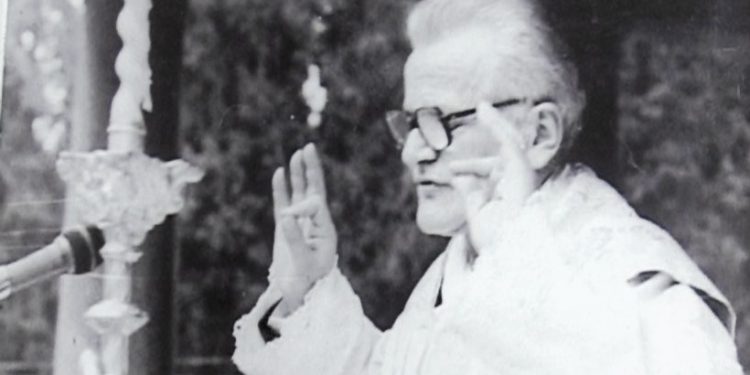

Father Gegë Luma was a man in his seventies. He had a short, slender body with a Socratic head, where a large, somewhat dancing forehead stood out. He also had a sharp and regular face, where two eyes stood out, to which shone both kindness and spirit and wisdom, as well as seriousness, determination and bravery. Father Gega, as a highlander and as a clergyman, had at his foundation two main elements: worship and steadfast obedience to God and the teachings of Christ, on the one hand, and steadfast endurance, typical of the classical highlanders of those parts. .

He had conducted in Italy two faculties at once, which was common for the priests and, in general, for the Catholic priests: the faculty of Theology, first and, secondly, that of the art of painting. But, in his life in the mountains, he had little or no field in the field of art, as he had served the teachings of religion more. When it came to this or that great classical painter, especially those of the great Italian Renaissance, he did not tire of praising Michelangelo, Raphael or Da Vinci. As for the later painting, before and after Cubism, he did not like to talk; why he did not know her at all, or why he might even despise her. Of course he also had a not bad literary background.

Sure, he knew Dante, Petrarch, but Boccaccio didn’t like him (it seems for Decameron’s liberal scenes). Meanwhile, he was praising a passage of Tassos in “Liberated Jerusalem” that, necessarily, had to do with the tomb of Christ. But, above all, he knew by heart the whole “Lahuta e Malësia” and, then, we started reciting together as we wandered around the prison yard; sometimes Marash Uci, and sometimes Kerni Gila. And so on. But in this regard, he passed me several times. Such a man could not but have a solid moral world.

I never saw in him signs of fear, trembling or despair. For him, life was nothing more than a test given to people to test whether they deserved eternal life in purgatory, in heaven, or in hell. Thus every iniquity of life, every danger, every predestined turn, for every man, by God himself. Therefore, one should be calm, patient, prudent and not give in to temptations, which are incitement of the devil, much less anger, resentment, revenge, wrongdoing, but always try to do good and only good.

But when I said to him (to be honest, with a certain devilishness), if we had to wash well with our executioners, for what they had worked for us and who continued to work for us, Father Gega would step for a moment in the face of gloomy, and only then did it shine again, as if from a divine inspiration, and return to me with the words of Christ on the cross: “Forgive, O Lord, for they do not know what they are doing!” Thus, in those few moments of reluctance to answer my question, he was inwardly, was in a struggle between the psychology of the mountains and the spirit of the Kanun and the teachings of Christ.

That petite old man, surprisingly strongly alive on the move and in every action of daily life, was loved and honored by all the prisoners, good and bad. His word was like a law that had to be obeyed because it does not. I have seen him many times between two quarrelsome groups, who were ready to fight with each other, not only separating the angry ones, but making a trial “. /Memorie.al

The next issue follows