By Taisa Pisha Batkina

The third part

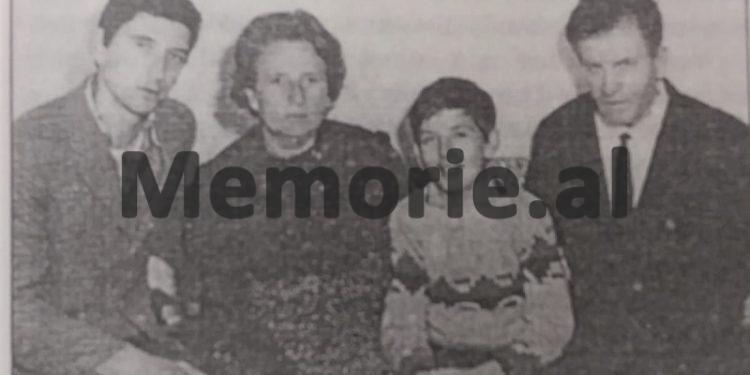

Memorie.al/ publishes the unknown story of the Russian Taisa Batkina (Pine), originally from Tula, Russia, the third child of a very poor rural family, who was left an orphan at a very young age, after her father lost her life while working in one of the coal galleries on the outskirts of Tula, where he worked as a miner, (shortly after escaping arrest, accused of “supporting the enemies of the people”) and she grew up with difficulty great economic, as their city continued to be under the bombardment of German forces, which had reached as far as near Kursk. Taisa graduated from the Faculty of Chemistry, near the ‘Lomonosov’ University of Moscow, where she met and married the Albanian student, Gaqo Pisha, originally from the city of Korça, who at that time was studying at the Faculty of Philosophy in Moscow and both together in 1957, they returned to Albania, together with their newborn son, Sasha, where they began life in the city of Tirana, Taisa was appointed as a professor of Chemistry at the State University of Tirana, while Gaqo, in the chair of Marxism- Leninism, where they worked until 1976, when the State Security arrested Taisa Batkin on fabricated charges, accusing her of being a “Soviet KGB agent” and sentencing her to ten years in political prison, which she suffered. in the “Women’s Prison” in the city “Stalin”, from where she was released in 1986, while her husband, Gaqo Pisha, had died in 1983, from a serious illness. The tragic story of Taisa Batkina (Pine), in the inhuman camps and prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, where she spent a decade of her life, along with many compatriots from the former Soviet Union, or other Eastern European countries, comes through her memories, published in a book entitled “We hoped and survived”, memories which, her son, Aleksandër Pisha, kindly offered her for publication, in Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

We hoped and survived

I dedicate it to the bright memory of my husband, GAQO PISHA

This is a book of memories. In it I want to tell about my life and that of my friends, Soviet women, who tried prison for several years just because they got the courage and got married and linked their fate with that of Albanian students. The prison was part of the great GULAG in the small Balkan country, Albania, where for many years the bloody communist regime of Enver Hoxha ruled, who was a loyal student of Stalin and a follower of his cause.

Through this book I would like everyone to learn about the inhuman trials we experienced and the horrible years we spent in Albanian prisons, just because… we fell in love! And let no one ever forget what totalitarianism, despotism is and what the consequences of this system are.

Years passed and I still have before my eyes the fates of many people, both those who fled and those who remained. Now we hear and mention the words “human rights”, but then we did not know the term at all; but I kept in my head intact the question that constantly tortured me: “Why should ordinary people, their families, and children be hostages of politics, why should we suffer, just because someone is fighting for power? Why? ” The answer was a single one: “This is a consequence of our socialist system, where the freedom of the person is completely lacking and the fate of the individual does not matter to anyone.”

Those who stayed in Albania had a very difficult life. For more than 30 years they did not see their loved ones. I will write about the fates of some of them in the next chapter. Many Albanians, whose wives and children fled for one reason or another, suffered deeply from this tragedy. At first they wrote to each other, but after a year the correspondence was stopped. Not that it was banned, but simply, the letters did not come anymore! When they went to the post office, they were told with an innocent look: “We have no letters, we do not keep the letters, apparently, they do not write to you…”. We women regularly received letters from home.

I remember Philip, who had become haunted. At the time of the break-up, the wife was visiting her mother with the children and did not return. “Taja,” he asked me, “what happened, why not letters come?” Meanwhile, the authorities, first in the form of advice, as among others, then in the form of threats, demanded that the men left only in Albania, to create new families. Someone got married easily, for someone else this was a laborious process.

In 1963, several people whose families had fled were arrested for attempted escape. I knew some of them. Noisy trials took place. Among them were: Leka Rafaeli, a military man, was sentenced to be shot. His wife was a doctor; fled the summer of 1961 with his daughter. Vangjel Lezho, a journalist, was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Later, in the camp, he was convicted again and shot. Some lucky ones managed to cross the border and join their wives, but these were very, very few. I remember how Sulejmani, a forest engineer, who lived not far from us, escaped. After his wife left, he married an Albanian woman, who was expecting a child… in a word, threw ashes in the eyes of the organs. Suleiman often went on duty in the mountains, and one fine day he crossed the border into Yugoslavia and arrived at his first family, in Moscow.

We experienced all this very badly, but what else could we do? We had to live and work further. It was impossible to escape, or, more accurately, we could escape, but only without the children, that the children would not give it to us. We lived in conditions of constant fear and insecurity.

Every family had its own tragedy. I remember how some people spoke to me when we met: “I got married”! How to apologize! Yes, they got married, started new families, but the pain, the concern for loved ones, and remained for a long time in their soul, even for some, until the end of life. I can tell you about some of them.

Rita and Ismaili. Wonderful people, very good family. They had a five-year-old daughter. Rita was loved by everyone, even her husband’s people, even at work. In Leningrad, Rita had left four elderly people: her grandmother, grandfather, mother and old aunt. From there they constantly sent telegrams, called them. The text was the same: “Come on, you are young, you will meet again, and we are old.” Rita fled. 10 years hoped to see each other again, waited for each other. Rita kept up correspondence with my mother, who wrote to me about them. (Other women had similar connections). In Tula, at my home after I returned, I found some of Rita’s letters in my mother’s archive. As I read them, the ’60s flashed before my eyes again. Some excerpts from these letters will tell you better than I do about the tragedy of these people.

Letter dated 29.07.1965:

“I am in a hurry to share my joy with you. I received a letter from my husband, it was sent by a boy from Bulgaria. Wonderful letter, 22 pages, with pictures. I realized that he is not broken, he preserves his inner world Ë He is a perfect man, I say this with full conviction. This letter gave me strength for a long time… I want to take a picture and send it to you… of course, to start… “. I took the pictures and took them to Ismail.

A letter dated 14.06.1965:

“Dear LJ You has to become strong and convince you that Taja has a good, excellent family and that means a lot… a lot…” This is how Rita tried to support my mother, who understood very well that this clash would to last too long, that she separated us and we will hardly meet again. And indeed it did. Ismaili experienced the departure of his wife and daughter. He suffered a lot, he waited, but… no hope! After 10 years, Rita got married, but could not write to Ismail about it. And he wrote to my mother: “I constantly try to force myself and ask you to inform me in Albania about my marriage, but I cannot decide…! Now please: write to Taja that I could no longer live alone and I got married. If I could tell you how much my heart aches for Ismail. But, perhaps, this will untie his hands… “!

The letter is from 1971.

When he received this news, Ismaili suffered greatly. But life does its own thing. Two years later he too got married. It was done with the girl. A year later, in 1975, he was arrested. Ismaili, one of the best mechanical engineers in the country, a lecturer at the University of Tirana, also fell victim to the horrific persecutions of the 1970s. The lawsuit: agitation and propaganda against the state, and the truth is: he had a Soviet wife and maintained good social relations with us. Ismaili spent 12 frightening years in prison. He was released only when the monolithic order began to waver in both the Soviet Union and Albania. Upon his release from prison, Ismaili tried to find his first family, as did many other Albanians. 30 years had passed! The children, who left at a very young age, had become parents themselves, the women were old. Their meetings have been varied; some of the children did not accept the fathers, they felt alien to each other, but even the spouses, after so many years of separation, often could not find a common language. They had been waiting for this meeting, they had dreamed it, but when they met, they realized that everything was gone, nothing connected them anymore. There was also tragedy. The father, in anticipation of meeting his daughter, suffers a heart attack and dies! But there were also many happy meetings. Some families reunited and, after 30-35 years, these people still live together. What happiness! One can live in peace, without turning one’s head away from power, from the government, from the party. Ismaili and Rita also met; Ismaili with his wife and daughter went to Leningrad. You could see everything there: joy, tears, and memories. The three girls (Rita also had a daughter from her second marriage), felt like sisters and got very close.

But let us return to Albania, in the period 1961-1966.

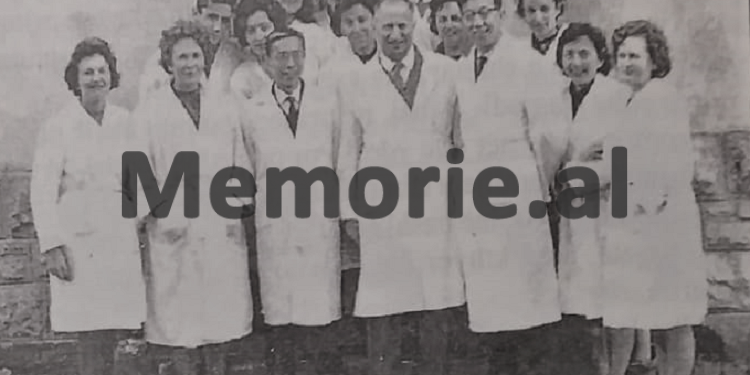

I told you above that I was educated in the spirit of faith in communist ideas, ideas of brotherhood, solidarity, etc. But slowly, under the influence of successive events, faith began to fade and the understanding of the true essence of communist ideas was gaining ground, emerging with us; I began to understand what this order was. Unfortunately, this understanding did not make me optimistic. During all this time, I continued to work at the university, teaching Chemistry, doing scientific work, and gathering material for my dissertation; however, the feeling of fear did not leave me. The years passed and the improvement of relations with the Soviet Union had no hope. In 1964 we rejoiced when Khrushchev was ousted; we remembered that the change of power would also bring about a change in relations between governments and our countries would at least restore diplomatic ties. It was soon seen that these were vain hopes. Above all, we were also concerned about the fact that my husband was constantly asked to obtain Albanian citizenship. Now, after so many years, my opposition seems ridiculous to me. It was a formal step that, to some extent, would make my life easier. In the end, I no longer had the hope of meeting people close to me. But at the time I thought differently; it seemed to me as if Soviet citizenship was the only thread that connected me to my loved ones, that at any moment I could ask to be allowed to leave. This hope, so ridiculous in those conditions, lived somewhere deep, in the farthest corner of my soul. Life seemed normal but politics, against my will, continued to interfere in my life. The great Cultural Revolution that started in China, though so far away, affected us as well.

At the end of 1966, word was heard about the “staff turnover”.

It never occurred to me that something like this would affect my family as well. Suddenly my husband got sick, and his hand began to shake. Doctors initially called this peripheral phenomenon and gave him sedatives, but his state of health was not improving. In August 1966, I was rushed to college. It could have been August 15 or 20, and our family was on vacation on the coast. We immediately returned to Tirana, to be at the university on time. At a meeting, we Faculty, me and several dozen other staff, were given the announcement that we would work outside Tirana, in order to bring to other districts of the country, our experience and our knowledge. Of course, this was a disguised purge. Through such tales, the unsuitable, mostly for political motives, were exterminated, and places were freed for the people and their friends. Later, I learned that my husband and I would be taken to Berat, a mountain town in the center of the country. Meanwhile, my husband’s health continued to deteriorate until he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Years 1966 – 1971

-Life and work in Berat-

On September 1, 1966 we left for Berat, where we had to live and work. They had moved us. We were cadres and did not belong to ourselves, we had to go to work, where to take us, where to assign us. This transfer was a tough test for us. At first, they transferred us, but they did not give us a house, we had nowhere to live, we could not take the children. The only option was the hotel room, but it did not fit in our pocket. Second, Gaqo was already seriously ill, but no one wanted to know. Third, normal life collapsed, I was no longer able to continue my unfinished scientific work, I lost hope of defending my dissertation. (At that time all these seemed very valuable things, but further life in Albania, put me in such trials, that the above events can be called minor concerns). Finally, we felt… how to say more precisely… half-exiled. As such they treated us in Berat, and as such they considered at first. My sick husband was appointed a teacher at the school. His state of health was now such that he could not teach, but no one wanted to know. To run the country, people were like chess pieces that you could move or throw away at will. And this was called “staff turnover”, the beginning of a campaign very similar to the Cultural Revolution of China, Albania’s greatest friend at the time. Many activities took place according to Chinese samples, the results of which we feel on our backs.

Huge lightning bolts on the walls of cities, factories, schools, which, in addition to criticism, often contained genuine persecution of unwanted people. Physical work had become mandatory for people of mental work, as well as military circulation and training. All this was done under the slogan of “revolutionizing Albanian society, strengthening the dictatorship of the proletariat.” There were plenty of slogans and slogans. Under one, “putting the general interest above the personal” deprived the peasants of their personal land and livelihood. Almost all the lands, gardens, vineyards, olive groves that were taken from the villagers were transferred to the agricultural cooperatives. They were no longer worked, turned into wastelands, into barren lands. The villagers opposed these measures as best they could. I remember a case; I do not know who told me. A peasant family in the south of the country, who had five rows of vineyards as their own garden, suddenly received the order: “The vineyard now belongs to the cooperative. You have to work all of them, and the harvest will be divided: one row of yours, four of the cooperative”. When the harvest began, they saw that the grapes were ripe only in one row, in the own one, while in the others there were almost none. This happened everywhere. The collective economy yielded less and less income.

In 1957, when I came to Albania, private shops were broken by meat, milk, fruits and vegetables. Then hand in hand everything started to fly. So that there would be no expressions of displeasure and no one would utter a word of complaint from the mouth, the terror intensified, and the screws were tightened. Those who did not live in Albania could not imagine the extent of the lack of freedoms in this country. The whole country, everyone was under strict control. In the cities the neighborhood councils functioned, in the village – the village councils. Without their permission, no one could move to another job, take or change the apartment, move to another city, start a high school or high school, etc. The councils also performed the functions of supervisor, controller, spy and cooperated closely with state bodies. Our life in Berat flowed in such conditions. For almost two years they did not give us a house, they did not allow us to make a change. My sick husband and I took a room in the hotel, where there were almost no facilities. Every week we went to Tirana, where the children lived with my mother-in-law. The journey was difficult, with buses or wagons full of bundles, of which they were very rare, or with occasional cars. In the combine, everyone knew that I had to go to the children in Tirana and they always informed me of any possible case. I held Soviet citizenship and, like any foreigner, had to obtain special permission to travel from one city to another. Every Friday I went to the branch of the city Ministry of Interior to get a pass. They often did not give it to me; they made fun of me, even though they knew very well that I had children in Tirana. Such a life required a lot of expenses: hotel, transportation, life in two houses… We could hardly close the month. Under such conditions, only work could be called… a ray of light!

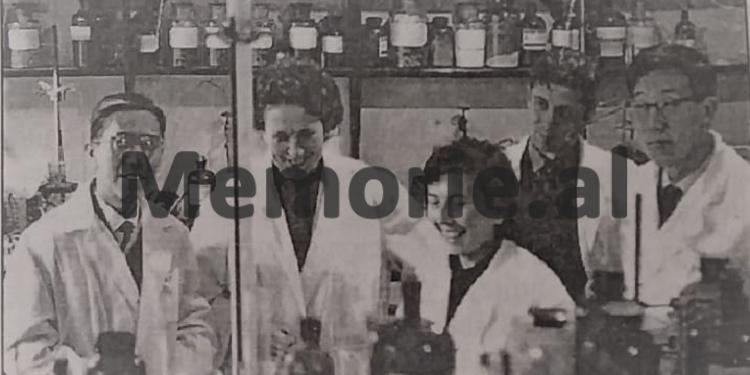

I was assigned to head the laboratory at the dye factory of the large Textile Combine, which was being built at the time with the help of Chinese specialists. I was never into coloring and I had to study a lot. Only after a year I learned all the details of the production, equipped the laboratory, prepared the laboratory technicians. My knowledge, apparently, was still working. I liked the work; it gave me that spiritual rest which helped me to survive. The plant was built on the field, which calmed my nerves somewhat. The city itself was located on the slopes of hills, in a narrow gorge, which was crossed by a river. And the mountains seemed to take my breath away, I could not see them. I had many friends in the combine. “Staff turnover”, had brought two or more specialists from Tirana, who had completed higher education abroad. There were also from my alumni. After returning from work, I rarely left home; I had not made it known in the city and I was afraid that I would arouse in the people the dissatisfaction of the authorities with regard to a foreigner. But I did not know whom to trust. At work I had plenty of clowns and spies, who darkened my life, slandered me, and spied. I found their reports in the thick files they showed me in jail during the investigation. When they finally gave us a house after a couple of years, we hurried to bring the luggage, took the children and I felt extremely happy that we were all reunited.

I was not sorry that I was fired from Tirana. For a long time I did not go anywhere, I wanted to stay at home; I could not see the cars and buses with my own eyes. The man’s health, meanwhile, was deteriorating. He was now disabled. One day, a doctor who had been my former student told us about a new American medicine for treating Parkinson’s. Thus began another war, the struggle to find that cure. There was no neurologist in Berat, he had to go to Tirana, to the hospital. Gaqo fell to his feet, to meet doctors from the Ministry of Health. After much effort, he managed to get permission to order the medicine overseas. Throughout my husband’s long illness; I have always had doctors, my former students, for whom I am very grateful, even now, after so many years. Gaqoja begged to be transferred to Tirana due to illness. Expectations were almost zero, but for a moment, when the spring of terror loosened slightly (there were such moments) we were transferred to Tirana. We were lucky and exchanged the Berat apartment with another in Tirana. I got a job in the Wood Combine lab, the kids were learning. Our whole life now was conditioned by the illness of the man, who was occasionally hospitalized. Meanwhile, the boys were learning brilliantly. I was afraid they would not be given the right to study at university, so I decided to get Albanian citizenship, as most of my friends had done. Sasha won the right to study. It seemed like everything was going well and beautiful. But…! /Memorie.al