Dashnor Kaloçi

Second part

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the former senior military, Major General Bako Dervishaj, former senior cadre in the partisan brigades during the Anti-Fascist War, regarding the events of September-October 1943, when after the capitulation of fascist Italy, some good troops armed by its soldiers and officers, they joined the Albanian partisans of the National Liberation Army led by Spiro Moisiu and Enver Hoxha. The Unknown Memoirs of Major General Dervishaj, author of several books of study on the period of the Anti-Fascist War, who in his latest book, entitled “With the Italians”, wrote among other things: “According to the terms of the capitulation, the Army The Italian IX was obliged to end military operations and hand over weapons to the Albanian Resistance forces. But Italian commander-in-chief Renzo Dalmaco refused. He ordered the military units to surrender to the Germans. Only 15,000 soldiers and officers of the “Florence” Division refuse to fall into the hands of the Nazis. Of these, 15,000 enlisted in the ranks of the Albanian Army, forming the “Antonio Gramshi” Battalion.

“On September 8, 1943, Benito Mussolini’s fascist Italy unconditionally signed the capitulation and abandoned its ally, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany. It was at this point that the long-running odyssey of survival began, of those thousands upon thousands of Italian soldiers and officers who once formed what was called “Mussolini’s legendary 8 million bayonet army.” Under the terms of the capitulation, the Italian Army IX was obliged to end its military operations and hand over its weapons to the Albanian Resistance forces. But Italian commander-in-chief Renzo Dalmaco refused. He ordered the military units to surrender to the Germans. Only 15,000 soldiers and officers of the “Florence” Division refuse to fall into the hands of the Nazis. Of these, 15,000 joined the ranks of the Albanian Army, forming the “Antonio Gramshi” Battalion. This is what Major-General Bako Dervishaj, a former commander in some of the partisan units during the Anti-Fascist War, writes in his memoirs, which stops at a long time, describing the unknown history of Italian soldiers who came as invaders and triumphants. in Albania, and then left defeated. One of the most interesting events he witnesses in his memoirs are those after the capitulation of the Italian army, where hundreds of Italian soldiers joined the Albanian partisans and fought in their ranks until the end of the War in November 1944.

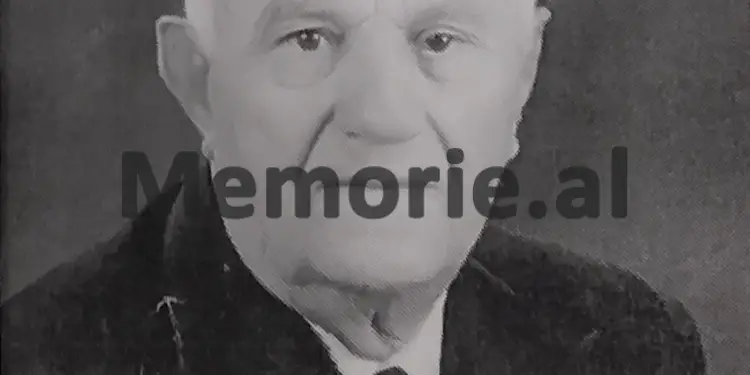

Memoirs of the former senior military, Major General, Bako Dervishaj

Continued from the previous issue

The capitulation of Italy in September 1943

Regarding the events of the capitulation period of fascist Italy, during the months of September-October 1943, the former senior military, Major General Bako Dervishaj, writes, among other things: that stormy time of war. He and other Italian doctors, after the world victory over Nazi-Fascism, became the leading doctors in the hospitals of the Albanian capital, Tirana. And I curse myself that in those times of war, I could not keep a diary of the names of all those Italians who shared their fate with us. The province of Mesaplik in the days of September until November 28, around three months, hosted in its bosom over 11,000 Italian soldiers and officers of that capitulated army, without any kind of civil or military organization. At that time I had the function of the commander of the province and was the political head of the National Liberation Council of the province. I wore a partisan “uniform”, which was a beret with a red star. I was in charge of the councils and volunteer teams of 19 villages. Such an organization brought order and tranquility to the province. In this situation, I was tasked with taking care of the Italian forces stationed in the center of the province. We defined an organizational plan that could be summarized in several points:

To ensure normalcy among the Italian military (11,000 men), who were disarmed, demoralized and hopeless. To protect them from any possible attack by the Germans or the Ballists, who at that time entered into an open alliance with the Germans. For those who dared to attack or forcefully treat the Italians, the law of war would apply, with only two articles (Article 1: pardon; Article 2: shooting). Guarantee of livelihood and clothing for 11,000 people. The Allied Command, through its missionaries close to the partisan commands, distributed gold money and coins to the Italians, for the purchase of food from the Albanian population of the area. In these conditions, in order to avoid possible speculations, it was decided that: To inform the whole population, that anyone could go to the Italian camp and sell them food or other means, for which they would have need, according to prices fixed by partisan representatives. Anyone who speculated on prices would have their goods confiscated. The seized goods would be distributed free of charge to the Italians. Village families in the area were commissioned. to help the Italians as much as they could, especially those who would be looking for work and housing. The Italians were advised not to try to seek any help from the Germans. (When a group of them, including some officers, tried to flee south to reach the port city of Saranda, near the village of Kuç, they encountered German forces, who, after separating the officers by the Italian soldiers, the officers shot them all.Germany thus became the common enemy).

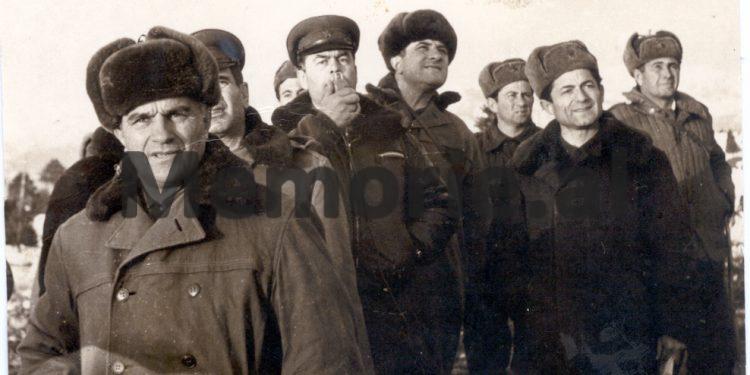

After that, the attempts to join the anti-fascist war were numerous and this would be very favorable for us as well, given the fact that they were an active force, which the Albanian nationalists or the Germans could use against us. “There were many Italians with strong physique and politically determined, who took part in our war, accepting the discipline and rules of the partisan army”, recalls the former senior military, Major General, Bako Dervishaj, regarding the deployment of 11,000 soldiers and Italian officers, who in the days of Benito Mussolini’s capitulation to fascist Italy surrendered to the partisan units of Enver Hoxha’s National Liberation Army.

Tough days

Regarding the further events of the Italian soldiers and officers who were installed in the district of Vlora, the former senior military, Bako Dervishaj recalls: “Around September 20, 1943, I paid a visit to the Italian camp along the Ramica River. Looking at all that unfortunate crowd of people, in the middle of the forest and under the shade of trees, I could not think I had anything to do with our former enemies, but I was trying to find opportunities to help them get out of that state of anxiety and sadness. I did not know what to do. They themselves did not know what to say to me and what to comfort them with. I heard them sing some melancholy Italian songs and in their voice I felt a longing that shook me. I was approached by two young officers (one was Celestino, the other I do not remember), who asked me to join our army, but after the problem of settling their comrades of the Mortar Company 82 m was solved / m. To this end, with the kindness that characterized them (and that we Albanians were so impressed), they asked me to give their company the opportunity to leave the camp, to then ensure settlement in the villages around the province of Mesapik. I pointed to a 10 km cave. away from there and I told them that the next day, the whole company could leave for there. I made it clear to them that the cave had only one entrance and was enough to accommodate 500 people inside. I then told them that as soon as they arrived, they could come and contact me, because my house was very close, and then we would discuss to take the necessary measures. We parted with understanding. After the mortar company arrived at Ramica Cave, the two officers paid a visit to my house. I offered you to eat the few things that were in my house, but with the motto of the Albanian: “bread, salt and heart”, and I advised their company to go out every day in the village in groups and so, slowly, to systematize and integrate with the daily life of the country. I gave my two guests a rifle and ordered them to use it without hesitation against anyone who would attempt to break into their “apartment”. Fortunately, on the part of the Albanian population, we had the right understanding. The Albanian people, with their intuition, knew how to distinguish between ordinary Italians and fascist fanatics, who had been sent to fight in a foreign country. Those young Italian boys were welcomed as friends, with a lot of generosity and warmth, as has always been traditionally Albanian. The village of Smokthinë consisted of almost 500 families and from this village about 650 people went to fight with weapons in hand. Of course, only the elderly and children at a very young age remained in these families. These families were sheltered by at least one Italian each, which turned into a moral norm so natural that it was hard to stay out of it. Over time, the Italians, one after the other, became associated with Albanian families, became homeowners and settled into various jobs. I remember that every Sunday, they made a habit of visiting each other in Albanian houses and praying to the elders, who had remained in the families, that for the invited friends, they could cook polenta (harapash), of course with butter and cheese, according to the possibilities in Albania of that time. Five Italian boys found shelter in my house. By this time five of us (brothers and sisters) had been involved in the course of the war and our mother, left alone at home with the youngest children, found solace in those Italian boys and became for them a second mother. She often said that: they too were mothers of sons and that bad luck and politics had brought them to these harsh lands, to fight against a people who did not have to be their enemy. Even those boys considered my mother as their own and became for her and for the partisans of the area, a great help. I remember one of them removing two stars from his spatulas and forgiving them to my nephew, Nowruz. My mother used to tell me that he was a very hardworking boy. With a sewing machine we had at home, he sewed shirts for partisans, with English parachute materials or bullet necklaces, with pieces of their military tents. During their stay in our province as “immigrants”, there were no sick or dead on the part of the Italians. They, sheltered and employed in Albanian rural families, were neither workers, nor servants, nor refugees. They were just freed captives and sheltered to protect themselves. They worked together in families, not to earn, but to increase agricultural and livestock production and to live on their own. The Anglo-American missionaries, meanwhile, had severed ties with us: they were neither seen nor heard from, and as a result, we had to manage only to provide food and clothing. Many commanders of the Italian forces, initially assisted by soldiers, then each began to think about their own destiny. I, Commander Bakoja, like all other partisans, was fed by the people with his cornbread. In those difficult times, it was not easy for me to talk to the Italians and approach their commanders, because I did not feel able to solve or cope with their problems and disasters. Apart from informing the population of the correct attitude they should have towards the Italians, I could do nothing materially for them, to alleviate their pain at all. The days passed and their food reserves became less and less. On one of the days when I was usually inspecting the Italian camp, an officer approached me and politely asked me for permission to slaughter a mule for their command, to be used as food. I was deeply moved by the request of that officer and the permission I certainly gave him. In those moments I started to think more seriously about finding ways or ways to help them get out of that situation. Thus, after some of my interventions near a partisan brigade, I was finally able to secure a not insignificant amount of corn for the Italians deployed in the Mesaplik area. At the same time I met Qeriba Derri, a friend of mine, who owned a mill, along with her husband, whom I ordered to grind with priority the corn that the Italian soldiers would take there. She not only helped them in this regard, but also sat down and talked at length with them about their concerns. Shortly afterwards, after she and her brother-in-law were shot by the Germans (her husband, the former commander of the Vlora district was wounded), the mill was left without a god, but an Italian named Giovanni took care of him (the Albanians easily called him Sulo ).

Company III

- Company Commander Lieutenant Giuseppe Ferari

- Company Commissioner Lieutenant Spaoli Gilberto

- N / Company Commander N / Lieutenant Agostino Rafani

Involvement of Italians in the War

At the beginning of October 1943, as every day, Celestino came to my house and informed me that all the Italians were already settled and in the meantime asked me to join the Albanian army. I felt very happy, thinking that my modest help had helped to raise their morale a little. As my sister, Rakibeja, was brought something to eat (Rakibeja was later killed by the Germans at the age of 17), I prepared an open pass so that they would not encounter obstacles until they met the first ward partisan. When he greeted me, Celestino gave me a pair of binoculars, which I kept until the end of the war. In those moments I did something I had seldom done in my life before: I prayed to God for their salvation…! It was the winter of 1943-1944. Along with the winter, the war between the Albanian resistance forces and the Nazi occupiers intensified. But while the Germans were armed to the teeth, dressed and barefoot, the partisans struggled to withstand the great cold hungry, racked and barefoot. And it was in the cold days of March 1944 that the Allies found a way to help us with weapons and clothing. At that time I had just been appointed commander of the III Battalion of the 5th Assault Brigade. I found the battalion near the village of Sevaster. I ordered my friends to distribute the aid. The distribution would be organized according to the needs of each, i.e. someone would get a pair of pants, someone else a jacket, and someone else a pair of shoes and so on. When I found out about Celestino and his friend that I had lost all contact with for 6 months, I ordered my partisan comrades to give them a complete uniform, from the bag to the shoes. The idea that they faced the harsh winter alongside the Albanian partisans and with a very “career” rich in anti-Nazi operations, impressed me. My order impressed my friends (since then I started to consider them as such). Shortly afterwards the two came and introduced themselves and asked me if perhaps any mistake had been made in the preferential distribution of the garments and if I was aware. After assuring them that there was no misunderstanding and that the partisan comrades had no objection, I saw how happy they were. And it was an almost, childish happiness that I could not and will not forget. I realized they felt good between us. I remember the war of Macukulli, from July 9-25, 1944. It was a difficult war. There we were killed by two partisans (one of whom was Sesto Tatare from Farli) and 7 partisans were seriously wounded (among whom Acorso Pietro from Arezzo). At the funeral of the two slain, the whole battalion gathered. It was not talked about for long, but the pain of all the friends was great. No Italian had been killed in our battalion until then. We were very sorry that an Italian was killed in foreign lands. We then rushed to move the injured. We changed the direction of the movement towards the village of Lis, to take them to the partisan hospital. The wounded Acorso was held in a vig and the companions who moved it took turn one after the other. As far as I remember, he was wounded in the chest. When he opened his eyes he looked at us as if asking for something from me. I tried to hold it with courage, but also to speed up the movement. Friends stood by and cared for him and the other wounded. The solidarity and sacrifices of the partisans in difficult moments were extraordinary and indescribable. The slogan “One for all and all for one”, was more than a human norm, more than a social and fraternal norm, it was an absolute law of existence, which can be understood only by those who have experienced partisan warfare. The Italian partisans became part of this solidarity. On August 23, 1944, we were in Peshkopi, Dibra district, on Korab Mountain and exactly on one of its peaks, Inoske, at an altitude of 2165 m. opposite us were German forces, who had two days on defense. As it turned out, both sides had planned the attack against each other. The next night, around 21.00, with three battalions of the 5th Brigade we launched an attack and exploded the German defense. They could not organize themselves in combat and immediately began withdrawing. After this defeat, the Germans accelerated the withdrawal and this garrison was the first to withdraw from the Balkans. As I watched the fighting from a checkpoint with Commissar Reiz Malile, I noticed that nearby, not far from the mortar position, was Celestono. I approached him and handed him the binoculars (which had once been his), so he could look too. When it was over I asked him how he looked with them. He replied that the binoculars had already found the owner and then added with a laugh: “The gift has served the anti-fascist alliance.” Meanwhile, Commissar Malile, who was accompanying me, asked “Are you a member of this alliance”? Celestino responded immediately: “Of course”, then added: “I am sorry that Italy is waiting for the rescue from the Anglo-American alliance, while Albania, small, is managing its own destiny. In mid-September, I was ordered to leave the 3rd Battalion in Kukës and return to the village of Shkalë in Tirana. The 1st Corps had already been created and I was appointed as the Chief of Information of the 1st Corps. I parted with my battalion comrades and the Italian partisans, whom I would never see again. I handed over the battalion to Hysen Çinos. Along with my will, there were messages for Celestino and other Italian partisans. When I arrived at the Korparmata headquarters, I learned with great sadness that the battalion commander, Hysen Çino (today “People’s Hero”) had been killed just two days after I left. When I came to Tirana, although on a different assignment, I tried to get information about my battalion in general and the Italian partisans in particular. The war was coming to an end and meanwhile the involvement of the Italians in the National Liberation War was becoming more and more organized. After the liberation of Tirana, I was very happy when I received information about the creation of the VI Battalion. On November 24, 1944, in Fushë-Kosovë (Lipian) the 5th Assault Brigade gathered and with all the Italian partisans of this brigade, the VI battalion was formed, consisting of three companies with about 180-200 partisans.

The leadership of the battalion was:

- Battalion Commander Captain Ernesto Celestino

- Commissar battalion Captain Giorgio Ghia

- Deputy Battalion Commander Captain Bruno Regno

- Deputy Political Commissar Lieutenant Izedin Bimo

The company of I

- Company Commander Lieutenant Franchini Fasco

- Company Commissar Lieutenant Agevati Xhino

- N / Company Commander N / Lieutenant Chinoti Natale

Company II

- Company Commander Lieutenant Gatto Renato

- Company Commissioner Lieutenant Fuxheli Axhelino

- N / Company Commander N / Lieutenant Aversaj Sidoro

This battalion had the right to carry the Italian flag with the 5-pointed star, which at that time had taken on the value of a symbol uniting all 5 continents in the anti-fascist war alliance. Its leaders were promoted according to the rules of the Anti-Fascist National Liberation Army. Thus, this battalion led by Celestino, for about 6-7 months took an active part in the fight against Nazi-Fascism in Kosovo and deeper, up to Visegrad in Yugoslavia. At the end of the military mission, the VI battalion joined the “Antonio Gramshi” regiment and then reorganized to return to armed Albania, from where, after gathering in the port city of Durres, they all left to Bari, Italy. (As I learned a little later, they were rounded up in Taranto, where they were disarmed and left free to return to their families. I remember we spent many moments of joy and pain together; we wandered for a very long time through that ordeal of marches and wars for freedom and independence, sometimes eaten and sometimes not, but I have never seen against them even the slightest sign of protest from my Albanian comrades. I created such a respect for them, that I was imposed by their behavior determined to fight for an ideal, which had nothing to do with themselves, but that they felt involved and that the path started together with us t ‘ they went all the way to fight those German cancer metastases that were spreading across Europe and Asia. As I said, these boys knew: Vlora, Gjirokastra, Përmet, Tirana, Burrel, Dibra, Kukës and penetrated deep into the body and soul of the Albanian people. These boys were admired for the courage and self-sacrifice they showed in the war alongside the partisan fighters and their time and work were given the well-deserved title “Freedom Fighters”. I recall here the saying of Tercilio Cardinale, Commander of the “Antonio Gramshi” Battalion, who states in his diary: “Albanian partisans did their best to express their friendship with us and included us as brothers in the fight against Nazi-Fascism” . My battalion, which included Celestino and the other Italians, fought for about 700 days. He described a South-North itinerary to Yugoslavia and in the long marches in the wars he described 2900 km of roads. This battalion gave the war 262 martyrs from an effective of 2400 men, including the occasional completion with volunteer forces. We shook hands. That glorious 700-day journey united us and unites us. Those days are related to actions and battles, to attacks and counterattacks, they are related to the blood of the fallen, of those Albanian and Italian sons and daughters who gave their lives to serve a sublime ideal: the liberation of Albania from the clutches of the Nazi occupation fascist. It is my right and that of my contemporaries; to remember with pride and nostalgia those ideals that go beyond a narrow nationalism, to the limit of a powerful ideal that even today (to be realistic) is not being experienced on. Today I understand the injustices of the post-war reactionary politics that disarmed Celestino and his comrades who had just arrived in Italy and the injustices of Albanian politics that forced me to lose all contact and connection with my comrades in war. Our ideals of the National Liberation War are not forgotten. They are engraved in Albanian folk songs, in the pages of the glorious epic of history, of that history of wars and continuous and joint efforts with the Italian people, which begins in 1460 with the great alliance of our National Hero, Gjergj Kastrioti -Skanderbeg and the Italian king, Alfonso Di Napoli, to whom the history of Albania and Italy, is attributed the victory over the invading Turkish army, a victory that saved Italy and Europe from the clutches of the savage Ottoman Empire. The alliance between the two countries was born naturally and will remain so, so history repeats itself. It was repeated in 1943 with the Italian-Albanian alliance, embodied in the “Antonio Gramshi” battalion. We are proud in history and masters of the protection of patriotic traditions, so we will always be proud and never be judged. Our friendship was linked in the war and “miraculously” was forgotten in peace. The friendship created in the trenches of the common war, but set aside by the circumstances, must be revived, in such a way as to serve the generations in the new Europe. It will be worthwhile for our great-grandchildren, when the time comes, to tell the story “Once Upon a Time.” And not to tell fairy tales, but to tell a great truth. We remained anti-fascists, and as such we have the moral right to be called patriots, humane, defenders of democracy and the most modern, humane and noble ideals that were not invented yesterday or today, but that we have the right to be proud of. . I am 82 years old and in good physical condition, retired general. It keeps me alive with the hope that one day I will be able to see them again, hear the voice of my friends or even receive a letter from those comrades with whom we shared the most beautiful ideal of our youth, ideals with which we bound the common war and that peace cannot separate us. These lines I wrote are just my modest memories. In the archives of the Albanian state and the Italian state, there are certainly many documents and facts which speak of those stormy events. I hope many of my friends are alive in Albania or Italy. What should we do? “How long will we have to do something?” for the Italian soldiers and officers, who after the capitulation of the fascist Italy of Benito Mussolini, surrendered to the National Liberation Army of Enver Hoxha, deciding to fight alongside them against the German army that was in Albania, where many of them even gave their lives being killed in some of the battles you fought against the German forces that were withdrawing from Albania. /Memorie.al