Dashnor Kaloçi

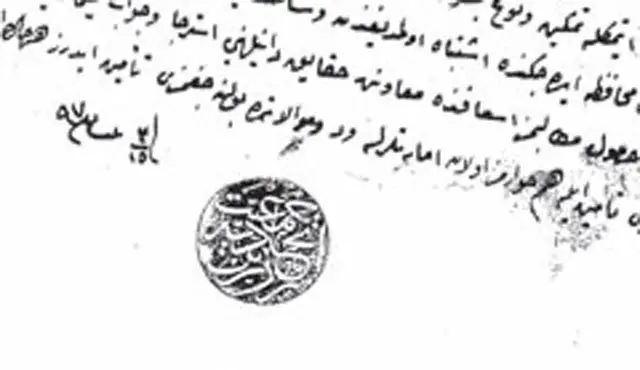

Memorie.al/Today, 143 years have passed since the day when on June 10, 1878, the Albanian League of Prizren was held, which in the history of Albania is considered one of the greatest events of our nation. During the period of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, the commemoration of this event became a common historical event and only in 1978, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of this League, that event was commemorated with a great commotion, putting into operation all state propaganda.

After the ’90s, when many of the events in the history of Albania began to be reviewed with all their positive and negative sides, even for the Albanian League of Prizren there were many different debates and controversies, as for the historical circumstances in which held it, the role of Turkey, the implementation of the decisions of the League, the participation or not in that meeting of Abdyl Frashëri and many, many other factors.

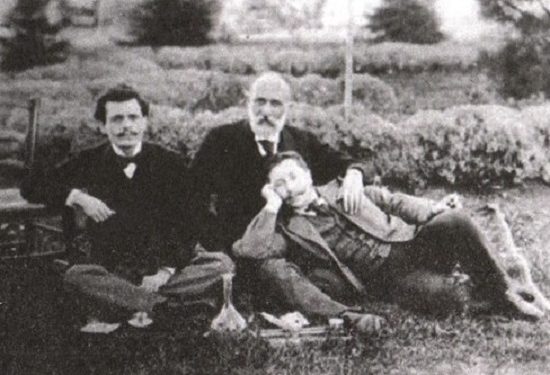

Regarding this historical event, in this article we are publishing an article by Abdyl Frashëri’s son, Mi’that Frashëri, one of the most prominent personalities of Albanian literature and also of the period of the Antifascist War (1939-1944), which he was published in 1928, in the magazine “Dituria”, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of that League.

Historical circumstances before the League

“The weather of 1928 represents for us a fiftieth anniversary of great importance, the beginning of movements that would leave their deep impression with the name League of Prizren, a movement that awakened and caused the creation of the Albanian Society of Istanbul. The lack of publications in the Albanian language, as well as not having in our hands today the memories and notes written from that time, as well as the fact that Albania was then visited and visited by foreigners, make us not have today in our hands the full subject matter for reconstituting those events.

For any historical study on this point we are therefore constrained to rely on personal recollections and on the scant help given to us by very limited publications. The League of Prizren was born from the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78. Victorious Russia was preparing for the partition of Turkey, imposing its conditions, seizing plots of land, some directly in its favor (south of the Caucasus), and others for the small Balkan states, its clients and agents.

And, if for itself it took depths from the body of Turkey, from the Balkans it also violated the Albanian land for a newly created state and only the Arbenian land for the three directly neighboring countries. This *** suddenly opened under the feet of the Albanians was arousing a reaction as if to say physiological, throwing the ball and throwing the pottery according to the vital habit of the people, a practice always repeated, in any case: The League of Prizren was probably at the top a local manifestation against land secession for the gain of Serbia and Bulgaria.

Here it is time to mention that with the word that appears as the title of this article, we do not want to show only the efforts that were made at the root of Sharit: but also the patriotic performances of Ioannina and Shkodra. There is no doubt that the change that is projected in the land statute of Albania, aroused an identical reaction, an instinctive defense in those two other centers: Russia on the one hand was bringing New Bulgaria to Devoll and Drin, on the other hand forgave Serbia Nis, Vranje, Kurshunlina, Leskovac as well as Montenegro, Podgorica, Shpuza, Guca, Plava, all anticipating for Greece a gift from Epirus. The three fronts of danger created three foci of opposition, of which, of course, the two northern ones would have material superiority, with the majority of the population, the strategic strength of the position and some relative independence vis-.-Vis Turkey.

On the other hand, moral and intellectual power would fall on them in the center of the south.

And indeed, when the north ignored the maneuvers of the shrines, being far from their centers, that is, not seeing them with the naked eye (because at that time propaganda and politics were played in St. Petersburg and not in Belgrade), Ioannina was a place of free of Greek actions and the aspirations of Hellenism saw no need to hide or disguise themselves. Only Shkodra directly felt the oppression of Cernagora, from the incessant wars between the two races.

The Russo-Turkish war was taking place after the wars of Germany and Italy for their national unity, following the principles of nationality that had begun to be seen as a preponderant element in the lives of peoples and states. Thus, even Russia, which pursued a purely selfish policy for its growth, and Russia, which raised its arms more for religious principles as a clash between the Cross and the Qur’an, at the end of the war was forced to pursue national ideas, to demand the fragmentation of Turkey for the victory of the various nations of Rumelia in the name of humanity, race, law and not only power. The ideas that fell were not unknown at all in Lower Albania: there Garibaldi’s patriotic epic, Mazzin’s humanitarian ideas, had found a hey, a forum for discussion.

The threat of Albania

In Ioannina again the weather war of 1870 had aroused great interest and it was natural that every movement, every new principle, would be followed with a practical curiosity in that center in which intellectualism was not lacking. The day after the war, the Russians went to the gates of Istanbul and imposed their will with the treaty of St. Stephen, was highlighting the danger that threatens Turkey, whose rotation in Rumeli is becoming very suspicious. This threat was even more special for Albania: if the Ottoman Empire was being threatened (threatened) as a state, the Arbenian land was being endangered as a race, as a nation and at a time when it comes to the rights of peoples and principles of humanity. Albanians, therefore, had to rely on arguments from a modern mentality to oppose their stance and complaints.

Here, too, the influence of the southern branch appears to us: in Prizren the people, compact and armed, with a conscience of their material power, as well as of supremacy over what, based their hopes on the strength of numbers and on the right to property. The less powerful South, being aware of its rights as a race and as a nation, was weighing on new principles that had overthrown old systems. This influence of the southern delegate was manifested in a more definite way, giving the movement a common, general, non-Albanian character, taking it out of the form of local claims, for the small homeland, for the vilayet and the cauldron; now the grievances and demands were for the whole of Albania, for the motherland, for the youth and the north, for the Muslims and the Christians, for every chip of the land and every individual who speaks the Albanian language.

It was probably the first time that the flower of the meaning of nationality was taking root in the rocks of Arberia and, of course, the new plant will develop in all its colors: from today to the expectation it was a single cap to make. And the next day began to preoccupy the connection and its branches more than the bad state of the day: you must secure the life of the nation and the motherland by making this nation and this motherland their rights recognized, respected in a in a way equal to the rights of those peoples in whose favor the Albanian land is sought to stand out. Breaking down and breaking old habits is being transferred to a diplomatic action; the simple and instinctive concern of the village was taking the form of a national and patriotic aspiration, with a higher and of course farther distance.

What did the League demand?

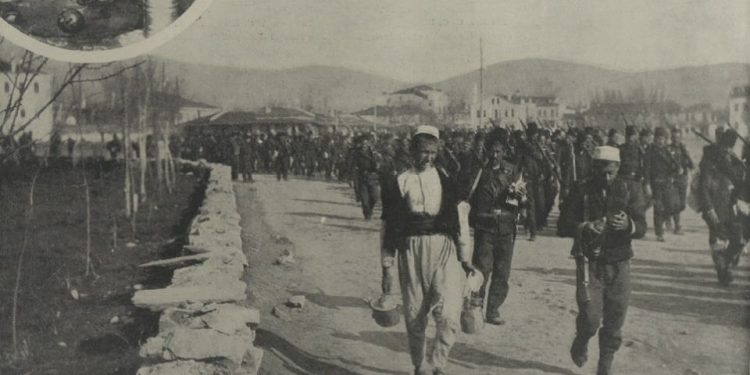

The reader will see in the bibliography chapter the nomenclature of a series of my articles in which I have tried to expose the work of the League, the various stages of its action, and the difficulties it has had to do with. Sadly, studies today on this movement, or the relative publications on it, are very few, even fewer when compared to its very main imposition. To many people, the League of Prizren can be presented as one of those uprisings that our people have always had in themselves, especially in the nineteenth century with Ali Tepelena and Bushatlli, as well as after them.

But the difference lies in the point that, when every first movement had as its initial impetus the activity of a single man relying on local tendencies needed by the circuits of the day, this time the initiative is taken by the people and the goal is found over the whole ethnographic Albania, on the day of action as well as on the next time. The League wanted not to divide Albania; but also demanded that the Arbenian land be recognized as Albania, that its rights be determined, that its life be respected; in a word an autonomous country, with administration and rule adapted. It was a colossal interpretation, with innumerable difficulties, internally and externally, in the body of the people and, moreover, on the part of the ruler of Istanbul.

Turkey at the beginning of the movement showed a pleasure in seeing the Albanians as a defender of the earthly integrity of the Ottoman Empire; but the nationalist and autonomist aspirations of the Albanians, perhaps more than anything else, the collaboration of all of Albania and all of the religious elements, made Turkey see the awakening of our mountains as a greater enemy than the Russian armies or the greed of Balkan states.

Even the brutal Turkish power did not manifest itself in Ulcinj as well as in Kaçanik.

The Turkish mentality at that time did not accept a nationalist idea, a common and united aspiration; the sultan’s policy based on division and division; the hope of domination was raised over the antagonism between the Tosks and the Ghegs of Christians and Muslims. He agreed that our highlanders should fight for their home and their pastures, but not for a moral entity they call their motherland.

The Prizren League was Albanian

There will no doubt be people who do not know the course of affairs or have been thrown into the stream of statements by interested neighbors and believe or have believed that the League is a creation of the Turkish government. As we said above, they are an answer for such. Can it be said that the League’s action remained barren? An action, an endeavor is always fabulous: it is the connection and the beginning of a new existence, even if it is confessed that you do not have an immediate result. In this world the effort to achieve a goal is perhaps of greater importance and value than the goal itself. Today’s combat is capital stored for the future, a living residual power that is exercised every minute and displayed forcefully in times of need.

Even so, the League, all having as a tree the delay in setting the border in Epirus in favor of Greece and then the rescue of that large part of Albania, had the biggest gain still to prepare our national life, to give them a meaning new aspirations of the people. From that day, indeed, begins the hope of a salvation, of a life more than fought in a certain form; since then the idea imagined by the word Albania takes on a clear form; the aspirations for a marked qok are molded and cooked. Localism and cantonism give way to patriotism; divisive and exile tendencies begin to weigh towards a single point; the provinces and elements that had reminded themselves of being separated and foreign to each other begin to unite, to feel solidarity.

In a word, tribes become a nation. This molding of the soul and desires, the creation of this new character cannot be done without a perseverance and long education based on moral and intellectual training. Another no less precious tree of the League of Prizren was for us the creation of the “Society of printed Albanian letters”. Forgotten, despised as a patois (fr. Dialect – red), viewed, not as a tool of civilization but perhaps, as a stoppage of progress, Albanian, with the founding of the Istanbul Society, begins to become alive and inspiring, of be an organ for giving ideas and aspirations, awakening feelings and inspiring thoughts. What we see today, what we expect from the future, what we have the right to ask from expectation, originates from the literary society, born from the movement of the League of Prizren. Memorie.al