Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes the unknown history of the organization and functioning of local government in Albania from the period of Ottoman rule to the period of the Zog Monarchy. How was the census of the people of Albania done in 1839, 1861 and 1882, based on a modern legislation from the most advanced of that time as in the western countries, which continued to be applied in our country until the ’30s. the last century, and the provision of Albanian citizens with passports and permits, who had to meet the following conditions: “Every person in the land of Albania, whose borders are set in the London and Florence Conference, is called Albanian and has all the rights qi derive from this quality. The originators of the lands of the Albanian State and residents of the lands of the above-mentioned Albanian State, from the entry into force of this agreement, will become citizens of the Albanian State. The people originating from the lands of the Albanian State and living in Turkey, at the time this agreement enters into force, remain Turkish citizens”.

In all the electoral campaigns that have taken place in Albania in these 30 years of the post-communist period, both in those of the parliamentary elections and in those of the local government, the two opposing political camps, among many mutual accusations, were those for not making the electoral register of the population and the possession of citizens with passports and identity cards. This does not seem to be entirely unfounded, given that: like the population register and identity cards, they are not unknown to our country. Even if we refer to history, we will see that they have been applied and used successfully in our country since almost two centuries ago, when Albania was under Ottoman rule. How was it possible to register the population of Albania from 1839 onwards, what was the legislation that regulated that enterprise, no less difficult for the conditions of that time, and how was the provision of Albanian citizens with passports and permits? All these and the way of organization and functioning of local government in Albania from the Tanzimat period to the Zog Monarchy, are discussed in several chapters of the book “Albanian Finances” published in 1934, by Haxhi Shkoza, (who during the years of the Zog Monarchy, served as Inspector General of Finance at the Royal Court), which Memorie.al brings for the first time in this article.

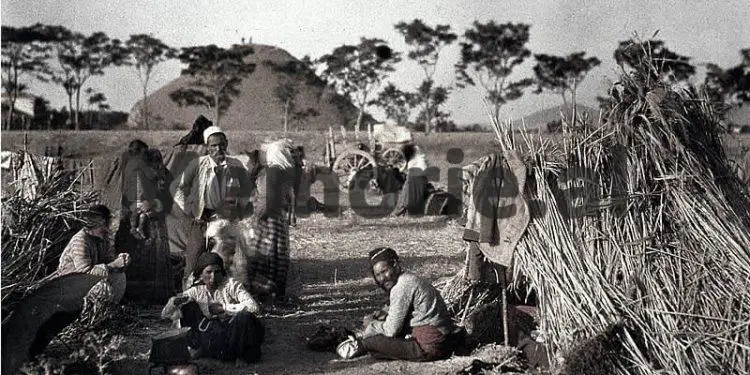

Population census and civil status offices

According to the data found in the book “Albanian Finances” of the author, Haxhi Shkoza, (former Inspector General of Finance in the Court of King Zog), published in 1934, during the Tanzimat period (1839), when our country was under Ottoman rule, for the first time the general census of the population of Albania took place. That general census of the population of Albania at that time, marked the laying of the first foundations of the organization of civil status offices, (or as they were known at that time: Krahinari), both in large centers, prefectures and municipalities, and in communes and villages. The census of Albania that took place in 1839, was repeated even after 20 years (in 1861), but this time it was on a sounder legal basis, as the relevant legislation in force for civil status actions was disciplined. As a result: in the registers of 1861, births, deaths, etc. were accurately recorded, including sanctions with severe legal penalties for offenders. A few years later, (in 1882), another initiative was taken for the general census, which was preceded by the establishment of an administration to ensure all the actions needed by the ‘Civil Registry’ offices. At this time, a regulation was drafted for the implementation of the legislation in force and another regulation for letter-notifications, adding to these the respective fees that the citizens had to pay for the services performed by the administration in the civil registers, etc. Thus, for each letter-notification, birth certificate, certificate of de-correction and change of place, the Albanian citizen had to pay as a mandatory tax: 1 grosh, (this is how the Albanian money was named at that time), while for the certificate of de-correction of girls, 5 grosh, and widows, 3 grosh. All profits from the letter-tax tax and half of the taxes on various documents were taken from the State Finance, while the other half from the religious parish. Receipt of notices was mandatory for all citizens. A few years later, around 1887, two supplementary laws were published, the first of which dealt with the fine of 2 gold francs for elders who did not notify in time of the minor changes, and the second with the fine of 4 gold francs for them that hid the actions, (non-registrations of family members, since they did not want to send their sons to nizam. Our note), which had to be reflected in the civil registers. This law was amended in 1902, and at this time with special provisions, the offices of the ‘Civil Registry’ were improved, but the taxes remained the same as they were, with the exception of that of the notices which for the poor would be free. These laws that were implemented in Albania at that time (with the exception of some Arab regions), were applied and enforced in all states and provinces that were then under the Ottoman Empire. The laws on the offices of the ‘Civil Registry’, or as it was otherwise called at the time, the ‘Offices of the Province’, were regularly applied until 1912, when Albania declared independence and seceded from the Ottoman Empire. Even the organization of the Provincial offices was applied until the period of the Austro-Hungarian occupation, which was found and implemented by the Government that emerged from the Congress of Lushnja in 1920. Although for all the censuses that were made in Albania from 1839 onwards (until 1889), all the relevant laws and taxes for civil status services are given in detail, in the study made by Haxhi Shkoza, in his voluminous book “Albanian Finances”), are not given figures on the population of Albania in those years.

Regulation of Albanian citizenship

According to the study conducted by Haxhi Shkoza, (former Inspector General of Finance at the Court of King Zog in the years of the Monarchy), which was published in 1934, during the Ottoman rule, the regulation of actions on the citizenship of Albanian states, turns out to have started by means of a law (exact date missing. our note), which consisted of nine articles. Regarding this, in the study in question of Haxhi Shkoza, among others it is written:

- “In order to have an idea on the provisions of this law, three of its articles are described below:

- Persons who allow, when their parents or only their father is with Ottoman citizenship, is called an Ottoman citizen.

- A person born in Turkey to foreign parents can rightly apply for Ottoman citizenship within three years, starting from the day of reaching the age of majority. An adult foreigner, if staying in Turkey for five consecutive years, can obtain Ottoman citizenship and apply to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, or through a mediator. Following this law, two annexes were promulgated, the first on 26 Jamazil-Ahar (Old Ottoman Calendar), and the second on 24 July 1875, on those who conceal their citizenship and on the impossibility of transferring the property of Ottoman subjects, qi die, among their foreign relatives. For the application of the law in question, a regulation and an appendix were announced, for which, since they are not included in the Ottoman Code, it was not possible to show their orders here. For the actions exercising on citizenship, the modifying tax (fee) has been received, the following of which is:

- For change of citizenship grosh 500

- For registration of the permit …. 20

- For obtaining Ottoman citizenship (T.GJ.C) 50

- For proof of citizenship (based on foreign act) 50

- For registration of all the above acts 10

- For actions of evidence on investigations 20

- For certificates, transcripts, etc. 50

- For proof of quality of citizenship 100

- For any request to the competent office 65

These provisions remained in force until the entry into force of the Royal Civil Code on 1.IV.1929. In 1922, the Government introduced the draft law on citizenship, which, no matter how much it was discussed by the Parliament, remained without any conclusion. The first article of this project was:

“Every human being in the land of Albania, whose borders were set at the London and Florence Conferences, is called Albanian and has all the rights that derive from this quality.” After almost three years, the treaty of friendship, the convention of establishment and citizenship between Albania and Turkey was signed, and they were decreed on 3.III.1925. Here are just a few of the provisions that apply to citizenship related to this chapter:

Art. 1. The originating persons of the lands of the Albanian State and residents of the lands of the above-mentioned Albanian State, from the entry into force of this agreement, will become citizens of the Albanian State.

Art. 2. The original people of the lands of the Albanian State and resident in Turkey, at the time when this agreement enters into force remain Turkish citizens.

Art. 3. The two contracting parties agree with the date of concluding a convention on housing and a citizenship agreement. The reasons for this connection are: Tue consider the intimacy of the ties that five centuries of political unity have left in the life and tradition of the two peoples: Tue was driven by mutual desire to strengthen and establish a relationship of sincere friendship as ma qi to be possible. “They are convinced that once and for all the relations between the two countries are established, they will benefit from the progress and prosperity.”

As can be seen from the explanations made by Haxhi Shkoza in his study, “Financat e Shqipnis”, which is illustrated by the relevant laws and articles that were in force at the time, the body of citizenship that was applied in Albania many years later., even to this day, has its origins in those laws applied since the middle of the XVIII century when Albania was under Ottoman rule.

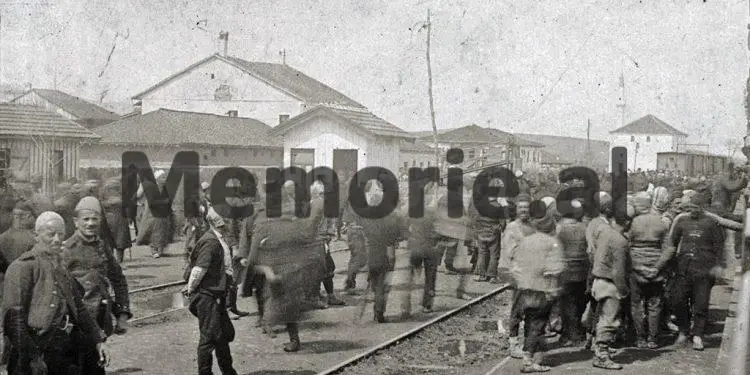

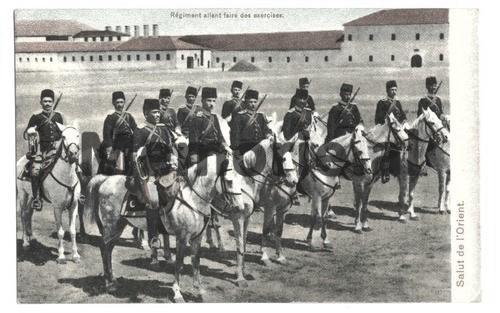

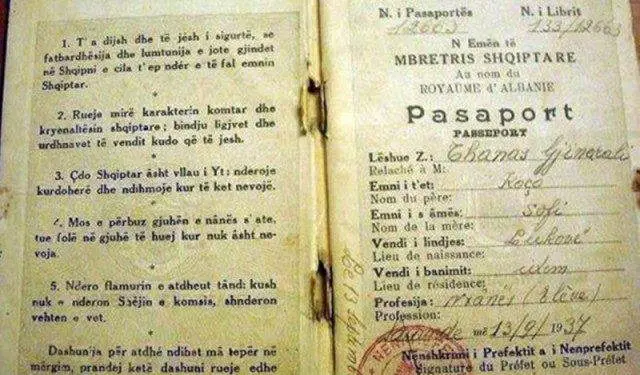

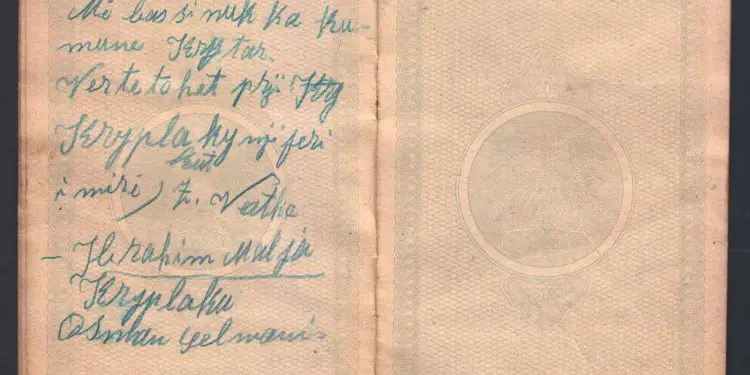

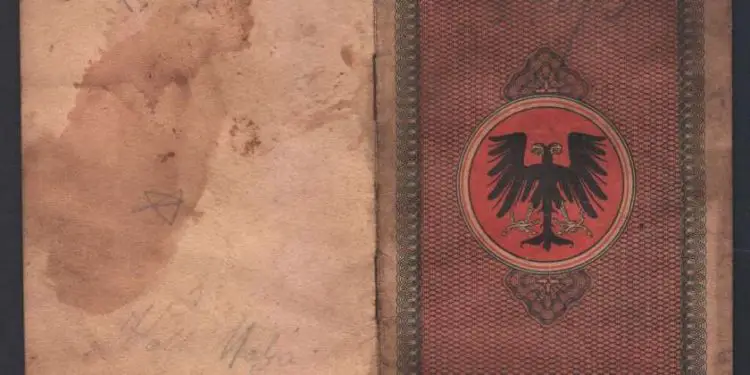

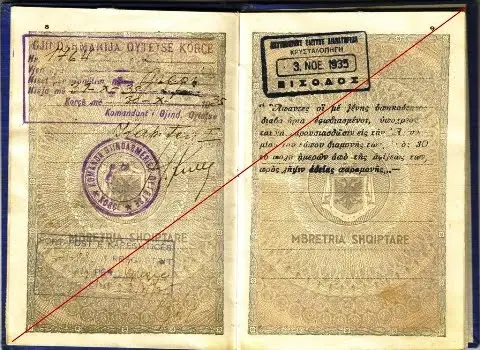

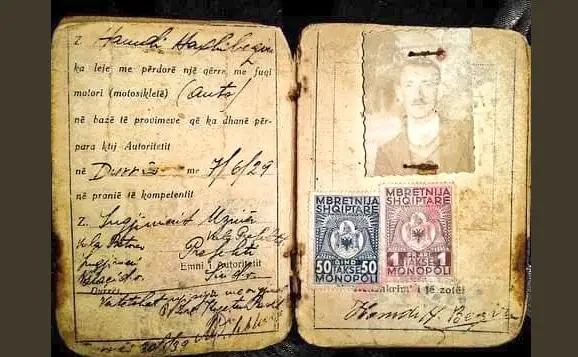

Passports and Permits in Albania since 1867

Throughout the period of Ottoman rule, as in all other states and territories under this empire, the provision of Albanian citizens with passports and permits was implemented with great rigor in Albania. Moreover, if we refer to the study made by Haxhi Shkoza (“Albanian Finance”) in 1934, we will see that those laws implemented by the Ottoman Empire at that time, were applied by the Albanian state until the middle of the years’ 30s. Regarding the application of the Albanian citizens with passports and permits, as well as the relevant laws that regulated that and the fines for offenders, in the study conducted by Haxhi Shkoza, among other things it is written: “This right is a kind of tax qi is taken against the issuance of an official document called “Passport”, which must be held by every citizen or foreigner who enters and leaves the border of the Kingdom. This tax, in the budget of the Ottoman rule of the time after the proclamation of Tanzimat, was added under the title ‘Harxhe’ which was formed from some taxes such as those of courts, civil status and others, and in the budget of our State is foreseen in section “Government Permits”, qi, and this includes some taxes such as consulting and others, which will be discussed in turn. The passport system, in the former Ottoman Empire, was implemented in 1867 under the law of the time. However, in this law, the provisions on the actions for issuing passports and their issuance are emphasized at length, but they do not foresee the rights that should be issued for these. Why this law was not complete and close to the relations that were developed at that time, we made the law dated 9.12 1883, qi, to modify some of us (articles) of the first one, has also set the passport tax for 50 grosh, and visa for 20 grosh. In addition, exemptions have been made for the poor to issue passports free of charge, provided that a certificate of poverty has been submitted by the local authorities. These passports were printed by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and given to applicants at the center by the Police Prefecture and in the counties by the civil status offices. Those who were in the Kingdom without a passport would be expelled, unless they were in a position to present a legal reason after which they could obtain a passport and pay double the relative tax: this rule also applied to those who lacked visas. etc. Later, a law was promulgated (November 24, 1894) that replaced the first two. This law, no matter how many changes are made in the rules on issuing passports, leaves their tax to be set as before. Also, this fine with gr. 100 all that qi enters the Kingdom without a passport and qi cannot be acquitted (justified). During the Ottoman rule, in addition to passports, the “passage permit” was also used (tezerski wall). A pass is an official document used for travel within the Kingdom that was to be held by every citizen and foreigner. The price qi was paid against the issuance of this was called the “right of way”. Passports were created by the law of 1861. Those who did not have ID cards were not given a pass. According to the law on the organization of provinces on 9.1.1870, the issuance of permits and the issuance of their rights, was entrusted to the officials of the ‘Civil Registry’ of the country with the exception of a short time that was entrusted to the police. With the implementation of the law on 27.VII.1887, a special importance was given to the actions on such permits, so much so that those over the age of 20, were forced to obtain a pass. This was only valid for one year; the poor were given free of charge. The rights to their permits and stamps were handed over to the country’s financial institutions at the end of each month. Finally, the pass-through tax. “With the budget law of 1910, it was suppressed to leave travel within the Kingdom free.”

Law: No passports for wanted persons

Throughout the period of Ottoman rule, until the 1930s when the Zog Monarchy continued to enforce laws on the issuance of passports and passports, the issuance of passports was prohibited for persons with criminal records or who were in police surveillance and surveillance. In this regard, in the study made by Haxhi Shkoza, among other things it is written: “The most complete law of the former Ottoman rule is that of 6 Xhamezai-Ahar 1329 (according to the old calendar, which in this case, i corresponds to 1911. Our note), qi consists of 20 articles. To give you an idea of the provisions of this law, here is a translation of some of the articles as follows: Those who travel outside the Ottoman Empire are free to obtain a passport. But those who enter this Kingdom are obliged to present their passport. The passport is valid for one year. The passport tax is 50 grosh, but for workers who go to neighboring foreign countries, it is 10 grosh. The poor are given free passports. Poverty must be proven by official evidence. Those who give or prove falsehood are fined a free Turk. Passports are not issued to those under police surveillance or travel has been banned by the courts. There is no visa fee for passports issued free of charge. The visa is valid only for one trip, but its term can be extended for another six months. Foreign nationals or Ottoman nationals who are in foreign countries must enter their passports at the Ottoman consulates when entering the Kingdom, otherwise they pay double the tax. These were the legal provisions that our State Administration inherited from the former Ottoman rule and which was accepted by the Provisional Government of Vlora in 1912. Unfortunately, it was not possible to find any text to guide if any changes were made to the provisions. for passports in the time of the first national Governments and in what way it was operated in the time of foreign occupations 1915-1920. In support of some of the notes listed below, it can be said that in the very first short period, our Governments did not have time to make any modifications to the legislation found and therefore have no doubt been kept in force. ottoman legal orders. But the occupying foreign powers seem to have made more or less changes, according to the need of abnormal time, to print in their own language, the passports and passports they needed, for example:

- Korça Administration: no passports were issued but travel permits were issued for travel to the occupied land.

- Vlora Administration: rules for issuing passports, permits, certificates and other police documents

- Administration of Shkodra: to Albania and abroad to be given passports like those of Austria to be translated point by point.

“In 1920, Albania was liberated from foreign occupying powers and the national government began to make decisions and design projects advised by the time.”

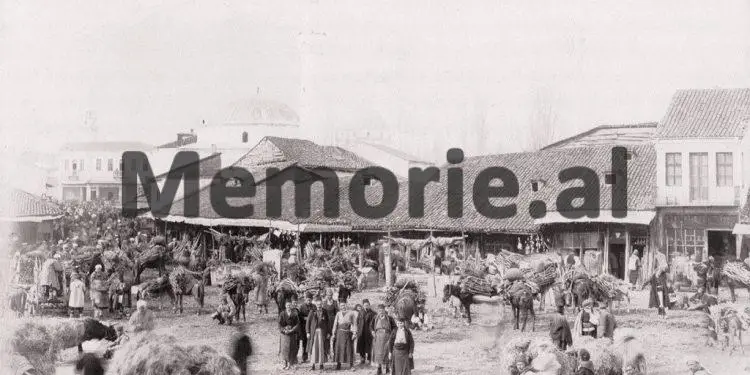

From the administrative division, to the staff of the clerks: How was the local government organized until the 20s of the last centuries

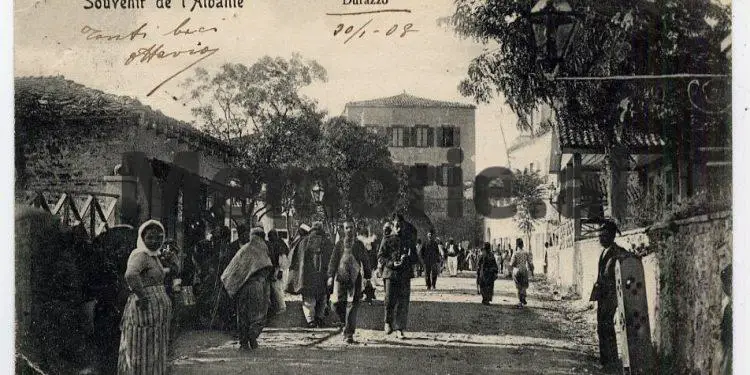

In 1920, the Provisional Government of Durrës printed and issued two regulations, one on local administration and the other on the election of administrative councils. Both regulations were signed by the then Minister of Internal Affairs, Myfit Libohova, and the relevant official at this department, Petro Poga, who were subordinate to the local government. Some of the articles of these regulations, among others, read:

“Albania is divided into 10 Prefectures, these are divided into 29 sub-prefectures and these into 43 provinces divided into 2545 villages, divided as follows: Berat 524, Shkodër 345, Gjinokastër 342, Korçë 331, Elbasan 310, Dibër 206, Durrës 182, Tirana 110, Kosovo 110, Vlonë 88. The head of the civil administration among the prefectures is the Prefect, in the sub-prefectures he is the Deputy Prefect, in the provinces, Krahinari, in the villages Plaku i katundit. The task of the sub-prefectures of the center of the Prefecture is entrusted to the prefects. Among the prefectures and sub-prefectures are the following administrative clerks: Director of Finance, Chief Secretary of the prefecture, Commander of the Gendarmerie, Director of Education (or school), Chief of the World Affairs, ay of Agriculture, Cadastre, Police Commissioner, Civil, the quarantine government doctor, the Port Captain and others that may be established. In the provinces, besides the Governor, there is also the Post-Commander of the Gendarmerie, and, if necessary, the Secretary of the province and the Commissioner of Police. The Deputy Prefect is the highest official of the Executive (executive) in that district and is obliged to protect the rights of the State and the People, to ensure the implementation of laws, etc., and is responsible for the general administration of the Sub-Prefecture. The duty of the deputy prefects of the center of the Prefecture is assigned to the prefects. And the governors have such duties for the part of their province. In each Prefecture and Sub-Prefecture there is an Administrative Council that has the task of conducting auctions, preparing conditions and contracts, selling data and other actions that are ordered by state laws. Among these councils, the decisions of the municipal councils are appealed within 5 days. Decisions of the administrative councils of the Prefecture may be appealed, within ten days of communication, to the Ministry of Internal Affairs; those of the councils of the sub-prefectures, within five days to be appealed to the Prefecture, and all this then to the Ministerial Council”. /Memorie.al