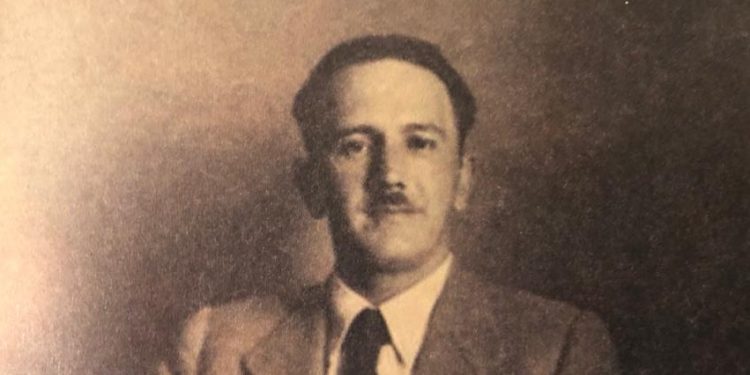

Ejëll Çoba

Part eight

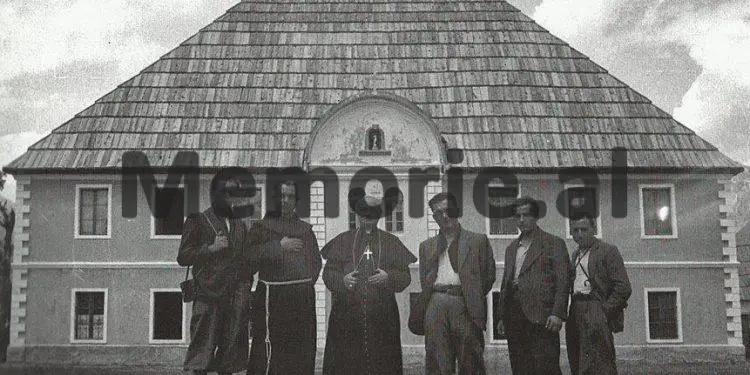

Memorie.al publishes some parts from the memoir of the author Ejëll Çoba, the well-known intellectual from the city of Shkodra, the sucker of one of the most famous families of that city, who after graduating from the University ‘La Sapienza’ of Rome in In 1932, he returned to his homeland where he practiced his profession, pursuing an administrative career, as ‘Dottore in Giurisprudenca’ and then for several years in the senior state administration, where he also occupied the period of occupation of the country, (1939- 1944), where he held several senior positions, as Director in the Ministry of Justice, Secretary General of the Council of Ministers, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, etc. His arrest in 1946, (together with his brother, Kelin) accused of participating in the ‘Postriba Movement’ and after a long investigation in Shkodra and Tirana, was sentenced to 25 years in prison, of which he suffered a full 23 years and five months, and five days in prison, in the terrible camps of forced labor, all the way to Burrell Hell. Ejell Çoba’s unknown memories, which come with a foreword by his fellow citizen, the well-known writer, Zija Çela, present to the reader a panorama ‘painted with the brush’ of pain, which provides details and details about his sufferings in the camps. of the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, as well as other accomplices, known and unknown names, such as: Father Bernardin Palaj, Guljelm Suma, Syrri Anamali, Ramdan Sokoli, Cin Serreqi, Father Karol Serreqi, Father Filip Mazrreku, Hamdi Isufi, Hafiz Ali Kraja, Beqir Çela, Musa Gjylbegu, Asim Abdurahmani, Prof. Selman Riza, Petrit Merlika, Kolec Deda, Nikoll Deda, Felatun Vila, Gjush Deda, Sali Vuçiterni, Emin Bakalli, Qani Katroshi, Sali Doda, etc., as well as some names of investigators, guards, State Security officers, such as Fadil Kapisyzi , etc.

Continued from the previous issue

CAMP

Memoirs written from early 1978 to…

The year 1948 came. The year of great changes in Eastern Europe. But life in Tirana prison continued at the same pace, until May, when one afternoon we were all gathered in the corridor of the prison, and a list of names of about 250 people was read to us, among whom I was. We immediately realized that we were assigned to work. Many were happy, because they wanted to go up in the air.

I always had in mind what the prisoners had suffered in the horror camp in Juba, in 1946, but a glimmer of hope in the treatment of prisoners at work was given to me by the fact that in 1947, the prisoners had not even been treated. so bad in agricultural work. Hamdi Isufi was not on the list, probably due to his age.

At the end of May, loaded like sardines in a truck, we traveled long, towards Vloçisht of Korça. The camp director, Tasi Marko, (Rita Marko’s brother), gave us a long talk, just as a baker could. He described to us the “extremely good” conditions of the treatment in the camp, the “sufficient and good food” and the “large and airy” silos and concluded that there was no need to wait for any of the families, even cigarettes, to give us camp as a reward for work.

In the camp we also found the prisoners of Korça and Elbasan. We had a total of 1,500 prisoners. We took shelter in large silos, with 500 people each. The hut was covered with a raincoat, and the sides were made of twigs and leaves.

The next day, without dimming the light, we went to work opening drainage canals. The workplace was at the gorge, and therefore very spacious. The road to get there was longer than half an hour, passing through mud and thorns. Our shoes were left in the mud. Hafiz Ali Kraja did not face them, he took them in his hand. He, who could not bear the coal in his English robe, walked barefoot through the mud of Maliqi!

From the first night, the comrades of the prisons of Korça and Elbasan, describe to us the hard work and the wild treatment. The first day I realized that, if that condition lasted, we would suffer a lot. I telegraphed to the family two pairs of rubber shoes, one for myself and one for Mark Dredha, who had no one to send it to. Young people, especially those in Tirana prison, who had a load of optimism and even euphoria, tried to cope with the hard work with courage. On the first Sunday, in the afternoon, they played football in the big square of the camp, where the command, taking care of the physical education of the prisoners, had set up all the gates for the game. That Sunday was the first and last day of the football game. The work of the week exhausted all the strength of even the strongest young people.

Every morning without a light, we went out in large numbers, 1500 people, to go to work. Even though we were 6 brigades, along the way we all came together, hitting each other next to each other, ready to run, being pushed by six internal guards, holding a sword in their hands like cowboys. About 50 armed guards surrounded us on all sides.

With us were also two prisoners from Durrës prison, who were his son. One had the name Dhimitër Tirana. One day, when he returned from work, the old man was left on the street, unable to walk and fell. The guards were released with sticks. Friends immediately informed the son that he was running with the others. He returned immediately, and as the guards continued to beat him to his feet, the boy, under a barrage of blows, loaded his father on his back and let him reach his comrades.

The guards continued to beat the boy, and your old man shouted, “Let go, let go!” In that condition, we charged, the boy continued for miles running to the camp. After a few days the old man died, but his son left us a great example, to show us how much power there is for the parent!

I do not forget the everyday look of a scene. Zef Nikaj, the grandson of the well-known writer Dom Ndoc Nikaj, then about 40 years old, used to take a poor old man, Aqile Tasin, from Përmeti, Koço Tasit’s brother, by the hand every day, and would not let him go to work to avoid the misfortune of the old man from Durrës. The guards were also used to seeing them by the hand, so much so that one day when Aqile Tasi did not go to work, the guard said to Zefi:

- Where is that blind man?

- He is not blind, but old! – Zefi answered.

The medical service was very deficient, not to mention non-existent. This is because they were prisoners: Lito, Hysenbegas and Treska. But rightly so they gave me a break, there was only Lito, as head doctor. There was also a nursing home with about 10-15 beds, and there was little or no medicine.

For the sake of truth, I must say that Dr. Lito has tried hard to come to the aid of the prisoners. But even a day off was not enough for the chief physician, because the guard of the day had to be accepted.

I had once killed a finger. After 3-4 days I got infected. In the evening I went for medication. Lito treated me, gave me three days off, and warned me that I had not gone before, that he would have given me leave for incapacity for work. When he saw the guards handcuffed him, he had nothing to say. Those three days were a real balm for me, because I recovered, because I was tired.

After about three months, one day at work, I noticed Dr. Isuf Hysenbegas, who was watching me push the cart. You seem to be impressed by my fatigue, that at dinner he called me to the infirmary. He talked to Lito and they put a few drops in my mouth, and they gave me a couple of days off. Without these days off, I would hardly have survived.

They all had visible signs of fatigue, as they could barely stand. I noticed an unknown phenomenon. Every day in the middle before we went to work, I saw that someone had changed their face, they did not respond and walked like vending machines. If it continued like this, they would die on foot.

I remember very well a villager from the Elbasan prison, where he was taken to a landfill. And he had to crush it and spread it with a hammer. When he saw that he had no power, I spread out the earth. But he was not even able to make the hammer. He could barely stand, they leaned on the hammer. The guards passing under the escarpment said to him: play with your hands. And they shot him with a machete. He left them desolate because he had no power, pretending to grab a machete and fall to the ground.

Thus, passed our day you knew. Five minutes before the whistle blew to finish work, it fell to the ground. He was dead. His last 10 hours of life had been spent in agony.

Another unit priest from Elbasan, ended in the same way. Doctor Lito took him to the hospital in Korça for treatment. After he recovered, he was fired. After two days of working, he died. Josif, called him and had studied at Grottaferrata. Sulejman Vuçiterni also died. The number of deaths in Vloçisht is innumerable.

A villager whose name I do not remember was suffering from nerves. He left, two or three meters away from the designated line, and entered a field of corn. The outside guard spoke to him but he remained confused. Friends called him to come back, but he did not move. It was clear he was not on his own. The guard then fired an automatic rifle into the air. We, with all the internal guards, entered the canal to escape the bullets. Then an inside guard stepped into the field and took the peasant by the arm, without any objection. At that time, the director of the camp, Tasi Marko, arrived, together with Tetar Ali from Lushnja. While the director was talking to the villager, the theater hit him with a stick on the head. He fell to his knees, but then got up and as he took a couple of steps, was shot with a stick in the back. He fell to the ground and died. The director ordered that a nearby tree be buried. We were ordered to continue the work. We only followed the crackling of pickaxes and shovels.

An hour later, an automatic battery was heard. Everyone stopped working. About three hundred yards from where I was, a guard had killed a prisoner. We immediately resumed work. The word spread that the prisoner had been a Zogist from Kruja, and that he had gone out for personal needs, without crossing the line. The inner guard had told the outsider to shoot him. And when the latter had not accepted, then the inner guard, grabs the machine gun and kills him. I saw four prisoners bring his body and sit it on the other dead, tree trunk. We worked about 1,500 prisoners, harder than ever.

An hour before work was completed, a guard ordered the prisoners to bury the two bodies in a pit on the escarpment. Prisoner squads brought them both and threw them into the pit like pendulums. Then, yes, they covered them with earth. The next day when we returned to work, I did not know where to find the two unfortunates buried. Victims of a vain and meaningless hatred. I did not imagine that the Albanian would do this to the Albanian.

I was ashamed to be human!

The work was always going on and getting heavier. The guards encouraged the squad-commanders, and they fell on our necks. To terrorize the workers, they began to take coercive measures against some, under the pretext that it was unthinkable. Me, Ihsan Libohova, and one of the villagers of Korça, who had been to America, gave us a plot to work on, and told us that if we finished, they would not give us food. Not that the dish was worth it, but we did not want to have consequences. And we put you to work by force. That “American” worked harder than us, but fortunately, Ihsan and I had a soft plot. The guard occasionally came, looked, and left unharmed. Before lunch we do the assigned part. They did not know what to say to us and allowed us to eat like everyone else. As usual, the list of those who did not follow the norm and those who opposed the squad-commanders was read before the meal.

That day after reading the list, the squad commander said: “Let the minister come out too!”. I knew that in our prison, there was no former minister but me. But I did not move, because I was not a minister, but a deputy minister. The guard who was next to the squad-commander, stood curiously for him without any minister. Since no one moved, they both remained silent and food distribution began. I got the dish too.

Me and Ihsan Libohova, did not allow us to work with others, but separately. One day when I finished work, I took the tools and went to the brigades, to work another part of the canal. After a while, Tetar Aliu came and sat on a hill, watching the workers in the Vloçisht camp. He called a team-commander of the Elbasan prison and after he greeted him militarily, he said:

- Do you see him tall with straw hats?

- “Yes,” he says, releasing the stick to strike him.

After hitting him on the target, he laid him on the ground. The squadron commander, after finishing this “job”, came to the theater and reported:

- The order was carried out, Mr. Tetar!

- Do you see that belly that has two quintals of buttocks?!

- How do you order! – and was released again with a bigger rush.

Big belly remained a whirlwind, while the 1,500 prisoners continued their work in complete silence. Tetar Aliu, as a general in battle, smoked cigarettes with pleasure.

After a while, Rusto Sharra, from Kavaja, a 45-year-old man, came to me.

- Should I also work on collecting this pile of soil?

- Well – I replied, pleased that I would have a friend in that job, really easy.

We worked for about half an hour. When Tetar Ali took him for a walk, he got off the ledge and headed to cross the canal. When he approached us a little, without saying a word, he attacked Rusto Sharra with fists and kicks, with the power of a 20-year-old boy.

Rusto Sharra lay on the ground, I did not stop working for a second, I did not blink, not even my eyelash. Tetari, came out on the side of the canal and move on slowly. Rusto Sharra got up and asked for half of the cigarette that had fallen from his mouth.

A couple of weeks later, I saw that squad-commander from the Elbasan prison, who came to work, was dragging one leg. Since he could no longer perform the task of squad commander, he was shoveled like the others.

Without the sun setting, Kamba froze you completely. They brought him to the camp with vig. Later, I learned that he had died in a prison in Elbasan.

Summer was coming to an end, the days were getting shorter, the cold, especially in the morning, was starting to be felt, the work was getting heavier and especially the hunger was getting very tired of the prisoners. The command itself realized that with cornbread, the workshop would greatly reduce yields. For this, from 700 gr. corn bread that we had the ration, they made us 900 gr. wheat. Of course, this bread made possible the fulfillment of the work plan and saved many lives of the prisoners.

To improve the bread, the Commander of the Camp, the blacksmith Tasi Marko, gave us a speech, praising the “care” of the authorities for the prisoners, and even informed us that from now on, instead of tea, they would give us coffee, not Abyssinia coffee like the Italians, but Brazil coffee. In fact, for about 15 days, instead of the juice we called tea, we drank the juice that Tasi Marko called Coffee Brazil!

We thought that we had discovered a quantity of coffee in the warehouse of a trader in Korça, and Tasi Marko, in order to get a bag for himself, had taken out a quantity for the labor forces of the Camp!

But if the coffee issue had its own explanation, the issue of the mattress wool remained unexplained for me!

One day, they took us out of the silos and insulted us, ‘bourgeois and tsarist’, accusing us that: when we were fired, we lay on a woolen mattress. Squadron commanders came in and took all the fur mattresses we had and put them in a warehouse. Luckily, I was not given a thick, large woolen blanket. I had to fold the triplet, lay two pairs on a mattress, and with the other, cover.

One evening, on our way home from work, I saw that about 100 postal packages had been opened inside the camp wires. As we waited in line to be counted before entering the wires, I told Rrok Gera I had her behind:

- After the packages arrived.

- God willing, we do not have it! – answer me. The packages were opened, checked, left in the sun on the edge of camp.

- “Churchill”, the pig of the camp, who had reached almost 100 kg, went to choose with his tourists, which he liked more.

An hour later, the camp accountant, named Faber, a jailed prisoner, called all those who had mail packages. I was among them. We gathered at the place of the packages. About five meters away from us, some 20-25 squad-commanders gathered, but nothing came of it. Under the direction of Tetar Ali, the accountant started calling us one by one to deliver the packages to us. He also called my name:

- Where are you from?

- From Shkodra.

- This time, Toska jumped on Gaga – Tetar Aliu, a baby, told me.

The accountant Faber, who was behind him, for fear of any reaction from me, crossed my eyes.

- They are brothers – I replied.

Tetari, did not speak. He checked my package once more, Sheldija took five buckets of tobacco, threw it at the group of team commanders, and also with four Yugoslav boxes of goose meat.

He gave me the leftovers of the package, 20 boxes of tobacco, two boxes of goose, two boxes of soltina, and two loaves of bread. Tue left, the words of Rrok Gera came to my mind: “God willing, we do not have…”! As with my package, do the same with the other 100 packages./Memorie.al

Continues in the next issue