Ejëll Çoba

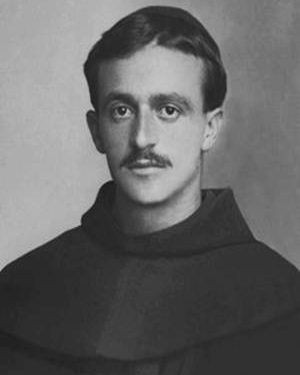

Second part

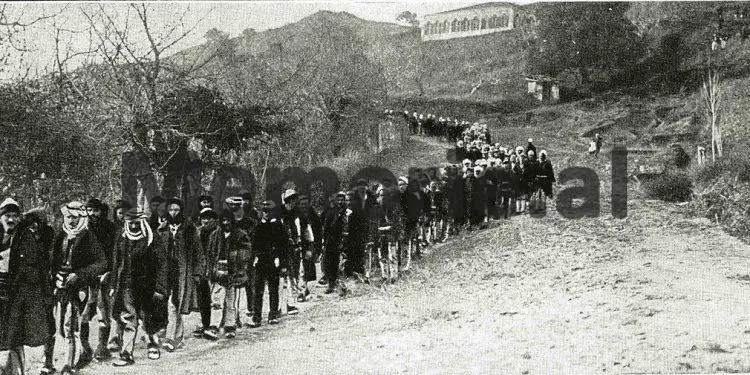

Memorie.al publishes some parts from the memoir of the author Ejëll Çoba, the well-known intellectual from the city of Shkodra, a sucker of one of the most famous families of that city, who after graduating from the University ‘La Sapienza’ of Rome in In 1932, he returned to his homeland where he practiced his profession, pursuing an administrative career, as ‘Dottore in Giurisprudenca’ and then for several years in the senior state administration, where he also occupied the period of occupation of the country, (1939- 1940), where he held several senior positions, as Director in the Ministry of Justice, Secretary General of the Council of Ministers, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, etc. His arrest in 1946, (together with his brother, Kelin) accused of participating in the ‘Postriba Movement’ and after a long investigation in Shkodra and Tirana, was sentenced to 25 years in prison, of which he suffered for years and five months and five days in prison, in the horrible labor camps, all the way to Burrell Hell. The unfamiliar memories of Ejell Çoba, which come with a foreword by his fellow citizen, the well-known writer, Zija Çela, present to the reader a panorama ‘painted with the brush’ of pain, where details and details are given about his sufferings in the camps. of the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, as well as other accomplices, known and unknown names, such as: Father Bernardin Palaj, Guljelm Suma, Syrri Anamali, Ramdan Sokoli, Cin Serreqi, Father Karol Serreqi, Father Filip Mazrreku, Hamdi Isufi, Hafiz Ali Kraja, Beqir Çela, Musa Gjylbegu, Asim Abdurahmani, Kolec Deda, Nikoll Deda, Felatun Vila, Gjush Deda, Sali Vuçiterni, Emin Bakalli, Qani Katroshi, Sali Doda, etc., as well as some names of investigators, guards, State Security officers, such as Fadil Kapisyzi, etc.

Continued from the previous issue

Imprisonments

Memoirs written from August 1973 to the end of December 1977

Only extreme things can be tolerated

Count Rober de Montesquieu

On December 25, the day of the Council, at about 11 o’clock, the prison captain came and said to me: “Come!”. I took the shoes I had at the bottom of the mattress, got up and went out with it. I was waiting for the transfer to Tirana, but after he did not tell me to take my clothes, such a thing did not occur to me. When I came out into the hallway, a guard tied my hands and the captain led me. We walked through the yard, went out in the alley “Sumej” and headed to a truck that had stopped in front of the door of the Sumej, my uncles. The guards who accompanied me removed the families who had come to bring food for the prisoners. While I was sitting in the alley, my sister approached me, who had come with a cousin to bring me food. He asked me, “Where are they taking you?” I replied, “I do not know.” A guard behind me threatened me.

I could not get on the truck as fast as I was, so a guard shrugged my shoulders and lifted me up. I went and sat on top of the truck. Six armed guards were sitting in the truck’s trunk, three on one side and three on the other. I between them. I still did not think of the transfer. I thought: feast day, the time before noon, when the people came out of the Mass at 11 o’clock from the Franciscan Church and made a lap at the piazza. I was reminded that Riza Dan was executed on the balcony, in front of a crowd of people, shouting: “On the rope, on the rope!”. I thought they were doing the same to me. We shaved for three weeks, with a face like in front of the rope, just a look for Ecce homo!

In the midst of these thoughts I saw again the sister, who had come out in front of the families, had approached the truck a little and was crying out loud. He thought they were taking me for execution. When she took her eyes off me, I thought of raising my tied hands, and signaled her to calm down, but it was in vain, that she continued even louder.

Meanwhile a lieutenant mounted the driver horn and the truck set off. Took the road “Skanderbeg”, left from Perashi. I started to think that we were for Tirana. But no! Enter the street of the Italian Consulate, (today the House of Culture). He stopped at Toga Prison, the former dormitory “Our Mountains”, and here we waited for a while. The sister came with the cousin with the food in hand. He approached the truck and said, “Here is Kelly.” Yes, I replied, “I know.” He was calm, because he was convinced that I was not going for execution. Vesonte shi. The lieutenant addressed the two girls in a harsh tone: “What do you want here, my friend?! Get away!” They sat down at Muzhan’s door with their eyes fixed on me.

From Toga Prison, they brought Hamdi Isufi, Musa Gjylbegu and Asim Abdurahman, who lined up in front of me. I still doubted whether we were for Tirana or for an exhibition. Truck and nis. I glanced once more at my sister. Anxious waiting with no direction we would take. The truck took the right of the Cell Field. The four of us were without anything with us. Even Hamdi Isufi had nothing in his head. It was raining lightly. I had no doubt they would shoot us on the balcony. But no! When we arrived at Kafja e Madhe, the truck turned left, turned around the garden, went and stopped at the former Ulqinak store (today the MAPO store). Here I made sure we were leaving for Tirana.

The truck left for Tirana. As we passed the Bahçallek Bridge, the lieutenant accompanying us and staying in the driver’s cab ordered us to stop. He got down, approached a partisan standing in the back of the truck and said: “Who is Hamdi Isufi?”. He asked me, as he was closer to me. “I do not know,” I replied. But Hamdia heard him and said: “I”.

The lieutenant then handed the partisan a piece of wire and told him to tie his hands once more. The rest of us did not deserve “this consideration”. They were enough to connect us with a long, fifth wire to the arm. So, each of us with our hands tied (Hamdia twice) and the fifth, tied by the arm, we set off towards Lezha.

I glanced at the thousand-year-old castle, the flooded field, the fog that had covered Mount Sheldia and the city that was weeping under a sky of bullets and under a thin rain like the silent tears of the people of Shkodra, mourning the lost bravery. For almost twenty-four years, I would never see my city again!

We went to Tirana without long stops. Only a couple of times did the driver get off to look at the engine, which was not working as well. Later, in prison, when we were talking about this trip with Hafiz and Hamdina, the latter told us: “Every time the truck stopped, I glanced at the side of the road and when I saw a small forest nearby, I thought I would go there. to shoot us”.

In Tirana we stopped at the Ministry of Interior (former Ministry of Finance). On the other sidewalk gathered a small crowd of people. They did not, but looked shyly. I only knew Xhafer Ypi’s son, and only one girl said in a loud voice: “There is also a priest”. He was impressed, that it seemed a rare thing.

The truck was then stopped again and stopped at Dr. Basho’s house, the District Headquarters or the Police Headquarters.

Finally, we headed to the Old Prison, on Shkodra Street. After we went down the inner stairs of the prison to lead to the corridor of the dungeons, Captain Shahini was waiting for us there, who with a look of superiority, said to us: “You do not like this republic”?!

Captain Shahini put me in a dungeon after making sure I had no acquaintances there. These investigations seemed sufficient to him, so he ordered me to stay in the corner of the dungeon, in the cement, and especially not to talk to the other members of the dungeon; and it came out calmly that he had done the task well. So wet to the marrow, I sat on the cement, in the deepest darkness and in the fullest silence.

I did not understand the dimensions of the dungeon, nor how many people were there. I had never visited Tirana Prison, although ours in 1939, I had been the President of the Court of First Instance, in the capital. Therefore, in the darkness of the Tirana dungeon, I tried to imagine their shape and size. After a few minutes, when everyone was sitting together, something happened that made me completely change the opinion I had formed about the environment.

A voice coming from above cried out, “Felatun!” said a few words in English. I did not know a word of English at the time. Immediately another voice from below answered in Albanian: “No, no one”. I thought someone had asked who had come to the dungeon young and out of fear the answer had been negative. By the name of Felatun, I had known only Felatun Villa, and I did not know anyone else by that name, so I thought he must have been in the dark dungeon, although I had no knowledge that he had been arrested.

The voice that had come from above remained a mystery. I thought that the dungeon would have two floors and that someone would be upstairs, or in some bed to rise a couple of meters. After Felatuni’s answer, silence fell again in the darkness of the dungeon. So, about an hour passed.

Suddenly the door of our dungeon opened and a beam of light entered from the corridor. Those who were in the dungeon, ran out and one of them got the courage and said to me: “Come on, we are going to the toilet”.

I came out after them too. We crossed the corridor and entered an alcove where there were four toilets in a row without gates, which were immediately occupied and I remained on that path in front of them. In the first toilet I saw a man sitting, who looked at me and with his fingers in his mouth silently gave me the understanding not to say that we knew each other. It was Felatun Vila. I also let him know with signs that he would stay calm, that I would fulfill his wish. When a seat was vacated, I entered. Everyone was doing their job, going out and waiting in the narrow street in front of the toilets. I realized that they

we’re waiting for me, so I hurried. Then they left for the dungeon and I followed them. We all went into the dungeon and the door closed.

Back in the dark, but I had realized that besides Gjushi and Felatun, there were two others I did not know. Before he fell, Gjushi told me: “At my feet, lean against the wall, there is a cardboard that I use for mahogany and if you want it, take it”.

I thanked him and got it. It was a 40 x 40cm cardboard. I sat on it, and this was my mattress for the evening of the Councils.

With Gjushi and Felatun, I saw a boy who told me that he had been a worker in Kuçova. Next to me was a man 45-50 years old. As the boy was talking to me, the other one said, “Don’t talk, do you know I have the bullet in my head?”

Shut up. The other one, after putting the dish in which he had eaten, stood up at the bottom of the mattress, and with his face against the wall, made a trish cross, stammered a couple of prayers in Greek, made a cross again and sat down. I became curious but did not dare to break that silence. He spoke and addressed me:

- I have been sentenced to death for 33 days.

- “Save me,” I replied flame to flame.

- Why? – he asked full of hope, we turned to him.

- “After 33 days, no one is executed,” I told him, “they did not obey me at all.”

He looked me in the eye full of hope. The security with which I spoke comforted him. The drowning is also caught for foam.

Silence again. It felt like we were in a mortuary room. We had the dead there. No one but him believed he would be saved. The others, except for the words of hope, had spent all and had nothing to say. I had come with new strength to give some hope. Nor did he fortunately ask me how I argued my opinion. Perhaps he was afraid of baseless arguments.

To break that heavy atmosphere, I asked him why he was convicted. “With Maliqi ‘s group”.

He told me that he had not admitted the charges against him and that he had not been brought to public trial with the engineers, Sharra, Manon and his wife. But they had a closed trial with a surveyor, Përmet. And the latter was sentenced to death and was in a nearby cell. Zani trembled. I could not look him in the eye lest I embarrass him. I was sure he was excited. Silence again.

- My name is Dhimitër, – he said and after giving himself strength he addressed us: Friends, I have a single girl in Korça. When you go out and meet him, tell him that he is dying innocent and that I have done nothing. ‘ And he burst into tears, saying, “Maid, maid.”

Thus, began the first day in the dungeons of the old prison in Tirana. For all my troubles I knew I was going to the death penalty, the case of the engineer awaiting the death sentence after 33 days touched me deeply. It gave me the impression of a man who had only looked after his own work and that he had supported the family with bread. And now he saw himself persecuted and sentenced to death, comforting them that he had accused himself of guilt as he had done.

Then came a man with a face without any expression, accompanied by two dungeon guards, and asked me.

- What do you have for Filip Çoba? – he told me in a heavy and wild tone.

- “Brother,” I said.

- He wanted to get involved in politics and become a great man. You have it here. He is in the dungeon too. And he turned to the guard and said, “Is that so, Vani?”

The guard nodded saying “Yes.”

- “My brother has never been involved in politics,” I replied.

- Yes, yes – he said, and started dealing with others. As he was leaving, he said to me, “Do not worry, I was joking.”

And the door slammed shut behind him.

The whole day passed almost without conversation. I wanted to start a conversation about why the words of the engineer were brought to me. Only after we ate lunch (I and the two franchises that were given to the prisoners) did Gjushi start telling me that he had been arrested since August, and that he had signed the trial. And since there were no serious accusations, he waited to be joined with the upper floor convicts. He asked me what had happened in Shkodra during this time.

I told him about the Postriba Movement, and about the executions that had taken place during the day, and about the imprisonments. I told him about his cousin, Pjetër Deda, who had been surrounded by his wife and apprentice. He and his wife were killed while the wounded apprentice was captured.

I told him about Simon Daragjati who had been thrown from the second floor of the Section, had died. I told him about Kel Deda, another cousin of his, Pjetër Deda’s brother, who had died in the investigation, and had been buried that night at Piri e Kirit. And the dogs had dug and exhumed his bones.

I did not tell him anything about Kolec Deda, his brother who had died and fell down the stairs in the Section. I told him that Dom Nikoll Deda had been shot. I saw that he was angry and I asked him “What do you have?”, “Brother”, he told me.

I saw that I was wrong and I did not continue for other arrests and executions. He did not want to hear from me either. He got up and was walking along the narrow corridor. He was gloomy and thoughtful. When I wanted to, I told him:

- What do you think?

- I’m thinking about family worries, as I have left my wife and three young sons without anything.

- Do not think of family worries, because they worry themselves.

- Even if I were there, I did not know how to organize the family, not my wife.

His words seemed appropriate to me. Woe to the one who dies, for the living have medicine.

With a push this day passed and we all lay down with the fall. Felatun had not risen and I had not heard his cry. I leaned against the corner of the wall towards Gjushi and my legs fell on the cement.

I prepared to sleep the second night in the dungeons of Tirana. My clothes were said on the body. The thoughts of the day made me tired and I fell asleep. The night seemed longer to me than a winter night.

The next day five officers opened the door and entered as if in large numbers. The first an elegant captain, went to Felatun. Four lieutenants in a row behind him, and a lieutenant in my direction. Everyone looked at me as a teenager. But the two lieutenants, as soon as they saw the engineer, Dhimitr, said “Are you still alive”? They rushed at him with their fists and kicks. The desolate engineer did not back down, but the two lieutenants jumped on the mattress, he did not worry, he returned stuck to the wall. Then the zealous lieutenants began to kick as much as they wanted. The engineer was so badly stuck to the wall that we did not know if he was breathing! We stood on our feet, yellowed and with tense nerves. I have never seen myself closer. The lieutenant approached me and with an ironic smile asked me:

- Who are you?

As I told him, he continued:

- What office did you have?

I told the judge, and he…

- Then?

- “Director at the Ministry of Justice,” I replied.

- Then? – And how to hear me better, he had raised his hand to the side of the ear.

- Secretary General of the Prime Minister.

- Then? And he brought his face closer to mine.

- Deputy Minister in the Council of Ministers.

- Then?

- Deputy Minister in the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

- Heee! – you do it with pleasure and shout high while I instinctively, turned my face away from him.

- Do not be afraid, we do not hit anyone – he told me.

The engineer was stuck in the wall and we did not know if he was breathing. The captain then ordered Gjush Deda, who was in charge of the investigation, to go to the other prisoners upstairs to be tried. The engineer was told to go to the geometer dungeon Përmet, Felatun’s mue, we were told to go to the dungeon opposite. After the officers left, I went out into the corridor because I had no clothes to collect, and I waited for the guard to open the door. I saw my blanket, I recognized it by color after we had taken it to my father, when he was arrested in 1915 and taken to Montenegro. With his father were Luigj Gurakuqi, Hil Mosi, Fejzi Alizoti, Preng Bib Doda, etc.

When I entered the dungeon, I found four people. I only knew Sali Vucitern. I looked at him, he looked at me and did not speak to me. Apparently, he had no desire to find out that we knew each other. Immediately after me came Felatuni, who said to me: “Here I was not told not to talk, so come and sit with me.”

When Sali heard that I was calling Felatun by name, he said:

- Are you Felatuni?

- Yes – he said.

- Aren’t you Angel Çoba?

- Yes – I said.

- I did not know you, but do you know me?

- We knew him but we did not know if he should know him – we told both of them.

We were so overwhelmed by the spirit of the section in the dungeons of Tirana, that we did not make them known to those we knew and were suffering with.

The others were: a Durrës man, a former officer, Qani Katroshi and Sali Doda from Mati, an old man. That weighed no more than 30 pounds. Maybe he was suffering from tuberculosis, and had been a driver in Shkodra, but I did not know him.

After exchanging a few common words with everyone, Felatuni and I started more personal conversations, Felatuni spoke a little louder and told me that in the dungeons there was severe torture, and that he himself had been subjected to torture, so much so that he had cut his veins and showed the pulse. He did not tell me, nor did I ask what they wanted from him.

Shortly before noon, they shared the ration of bread and Qani, Sali and I, brought us the dishes that the family had brought us. I did not know the dishes because how I had ever seen them at home. Felatuni understood my surprise and said to me:

- If your brother subscribes to the restaurant, the dishes are theirs.

- Let’s eat together! – I said.

- I am still tortured because they often call me and do not give me the food that my family brings me.

- I do not know about these things, so I told him to sit down and eat.

We sat down and enjoyed the restaurant food. I had two days to feed the two prison fringes and Felatuni does not know how many days he had.

I waited all day to get the layers. I told the guard that I was without my clothes. “They are not yours,” was his reply. That night I slept on a mattress and the next day we handed over the mattresses. But another rage was added to me. The label that had my name was written by the sister I had left in Shkodra. I knew my third brother in Tirana. Why did my sister come to Tirana, when my brother was here? I began to doubt the words of the Director of the Prison, that the third brother had also been arrested. Three brothers in prison. Nana with sister at home. I was waiting for a trial, the outcome of which was not at all favorable. Very few were the hopes of life forgiveness for those who surrendered. Terrible prospect of torture. We arrested the brothers, the mother with the sister only. In the atmosphere of imprisonment and executions that was created in Albania and especially in Shkodra in the years 1946-1947, anything could be expected. And why? Because Tito’s Yugoslavs and Stalin’s Russians, whose orders the Albanian Marxists carried out, wanted. If that was the name of those in power in Albania.

After noon I burned the feet of people coming down the stairs. Felatuni told me that it was the investigators who came to interrogate and continued until late at night./Memorie.al

Continues tomorrow