Nazmi Berisha

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of Nazmi Berisha, originally from the village of Llap in the Municipality of Podujeva in Kosovo, who was seduced by the propaganda of the communist regime and the programs provided by Radio Tirana for “socialist prosperity” and escaping the rank-and-file methods of the Titoist regime, in 1960, he decided to flee and came to Albania, crossing the Buna River by swimming in the great cold of that harsh winter. The rare testimonies of Nazmi Berisha, how he was received in his homeland, where the soldiers and border officers of the Shkodra district, after tying him with wire, sent him to the Internal Affairs Branch, where for 24 hours they did not even give him bread for eaten, and then sent to the town of Shijak where was the “Filtering Center” of Kosovar emigrants. The whole adventure of the 20-year-old boy from Kosovo that the State Security accused of: being a UDB agent, who had sent on a secret mission, Cedo Topallovic, the president of the UDB for Kosovo, to meet with the Rear Admiral of the Fleet, Teme Sejko and the inhuman tortures inflicted on him in the Internal Affairs Branches of Lushnja, Kruja, Tirana, etc., where he was kept in solitary confinement and asked to become a State Security collaborator, as witnesses, his compatriots from Kosovo, and his refusal, which made him spend 20 years in the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha.

“Once through my situation as a somnabul, I asked for a meeting with Mehmet Shehu, arguing in front of them that he was brave and the brave neither forgave nor killed. Upon my request, I was not allowed to meet with the Prime Minister, but a Security General named Nevazt Haznedari was brought to me. As he entered me, the general threw his arms around my neck and hugged me. I could not judge in those moments for the real motives of his behavior, but I was confused by that. He was rosy, shaved, handsome, and serious-looking and healthy, and the general’s clothes looked good on him. He asked the officers about me and they told him I had not accepted anything. He immediately addressed me, saying: “How can you not be ashamed to deny the deed you have done, do you remember that we do not know who sent you to Albania”?! This is how Nazmi Berisha recalled, among other things, his meeting with the infamous general, Nevza Haznedari, the former head of the Investigation, after the request he had made to meet with Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu, while he was in the dark cells of the State Security. Nazmiu, also known as Dyzi, fled Yugoslavia to Albania in 1959, after years of permanent residence as a political asylum seeker in Oslo, Norway, where he settled after his repatriation in 1980, recounts the adventure his tragic how he spent 20 years in the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, accused of being an agent of the UDB.

My adventure from Kosovo to Albania

The one who rocked me as if I were quite small, a minor, is my native village. Dyzi i Llapit (Municipality of Podujeva) certainly did not give birth to only one son. He, Dyzi, has a life as long as the seasons, no one remembers them. Dyzi, gave birth to Mehmet, my father, and he gave birth to me in 1938. As I grew older, I felt the cruel injustices that originated with the flag removed. It was not us who tried the double whip of life and the Serbian occupier.

The occupations were not over: the action of collecting weapons, the action of deportation to Turkey, leaving the ancestral hearths with tears in their eyes and broken souls. Trains at Prishtina station, loaded cheap goods, Albanians! Even later, others would embark on new paths in exile. A creepy farewell. I cannot forget my friends kissing the thresholds, touching the door handle with horror. Often everyone looks to me like the old woman of my street, who when she left for the station, burst to the ground, kissed the ground well and with tears in her eyes boarded the cursed train.

Finally, he came to our house, Albania! What a joy! What a surprise! Even tears. My father once bought a radio and we were listening to Radio Tirana for the first time. It was the May 1 parade. Hundreds of thousands of workers, peasants, students, pupils, soldiers paraded. Oh god! What pride! I even heard Enver Hoxha, the so-called legendary leader of Albania, speak. To be honest, that voice filled my heart.

The idea stuck in me that soon, Albania beyond and Albania here, will be together. And I would one day embrace that man named Enver. This sudden dream with all my eyes open would become my first motive afterwards. All our evil, as in the spirit of God would end. That voice, that speech, that parade was enough! You only heard him cursing the Serbs, he was bluntly telling the truth, about the life of Albanians, about the closure of Albanian schools, about the forcible expulsion of thousands of Albanians in Turkey and elsewhere, about the beatings and many other barbarisms.

From the resounding voice of Enver Hoxha, the house was still shaking. I believed that from that voice, the date was passed to the Yugoslavs. As for me, the curious without side, when that happy day would come to see the happy faces of Albanians, their smiles, to hear warm words. But, oh mother, what a wonder: Later I would find out in horror, that people walked to work and did not look either left or right. Hidden from the world and from themselves. And to my surprise I began to remember how precious freedom is. That, would these things happen, if they were not under the vampire hooves of the Serbs?

Question that has an answer. Except I did not know anything at that time about the real hell where Albanians lived! And the bombastic words on the radio, to give confidence and inspire hope. And where were the low voices of the chamber hidden? Not even the voice of my father or my uncle was being heard. Fliste Radio Tirana!”

As the invisible hand grabbed me by the hair and stretched me up, for me the direction from Albania became more and more clear. He yes, was the only place I could live free. He worked enthusiastically, plans were realized every month and every year, factories, hospitals, roads, ambulances were built (even in the most remote villages), there was a lack of human exploitation, only happiness flowed in all human eyes! Here I had these embedded in my still small head.

Physically I lived in Prishtina, but spiritually I was in Albania. Those nights the idea of fleeing to Albania was well established. The great hope that we would not help our cause even better, it seemed to give us inspiration. I was often upset and it was as if my mother Albania was breastfeeding me. Something unpleasant on the road, at home or with people, did not despair me anymore: I would soon fly and like a winged bird I would be in the heart of my homeland. And this was not just a decision of mine.

My friends made the same decision. Maybe one day they would return to Kosovo with weapons in hand, as liberators, like the heroes of Dervish Shaqa. I would go like this to the free and wonderful country, Albania! It was advertising and desire that forced the heart to beat with arrhythmia.

When would we leave for Albania? That was the feverishly shocking question. My place had to do with another feeling, I lived in Prishtina, but my mind was beating away. While walking with her friends in her promenade, visiting her cinema, breathing in her fresh air, with my mind I experienced that flourishing place, the rest beyond the Berlin Wall – in my Albania. That mine is. That Prishtina is also Albania.

I decided to run away. The dilemma of finding the best ways. I would be alone. How strongly my friends break my arm. But they will not defeat me. I finally decided. I took the train to Rijeka, then by bus to Ulcinj. There, too, another Albania approached me by the sea, one of the very western extremities of my country. I was tired, overwhelmed, but the hope that I would soon be in Albania, I would cross the wall, blacker than that of Berlin, kept me alive.

So, I would see my Albania and I would kiss right on the forehead. It soon became dark, and I, with the hungry man’s vertebrae, threw myself at Buna. First, she avoided a suspicious villager, then the first part of the night and her infidelity, huddling at the foot of the mountain. There I could chew new thoughts and tricks. My dream was sponge. The lights of Ulcinj shone away from me. The only one in front of Buna, its width, its angular shores, untested waters.

You think the enemy away and he who does not think, suddenly becomes your enemy. However, I sewed the waves naked. I was choking on the cold, Abyss. And I buried the river. It was my most powerful dream. My ideal overcame the waves and the cold. At last! I kissed the ground across the Buna. What I experienced is a bit to be called joy. Even in joy you have to be frugal. While I, alone, was terrified of the extraordinary joy.

The first real thought in the dream land was to surrender to the police. But I did not see any human legs. I could not hear the voice of man or cattle anywhere. To wait for the light to fade and orient myself somewhere or to walk? I waited for a while and then when dawn was revealing the contours of the mother earth, I set off for where my feet were leading me. The second real thought seemed to scare me. Do the Albanian border guards, not knowing who I was and calling me a saboteur, shoot me without warning? Dangerous border crossing game.

What should I do then? To walk, to move forward, or to be shy? I once saw some sheep. I rejoiced as a child. The sheep would have their own shepherd and the shepherd knew the army post command. Although I mingled with the sheep, I did not see the shepherd anywhere. It seemed to me that somewhere I saw a light still on, even though it was already day. My first call near that house was: O Albanians, the answer came to me in the form of a question: who are you? At that moment he fired a gun and an order like a shot, hands up. I raised my hands, though an offensive thought passed me by. Eh! What was offensive to me coming to Albania? My heart swelled with emotion, why would I look at the soldiers and policemen of the motherland.

Nothing scared me anymore. Two soldiers came running and quickly tied my hands behind my back with a belt. I was happy to see the Albanian soldiers, again I was left without an identity, who I was and where I came from. The soldiers ordered me to move forward. They were very serious, as befitted the soldiers of Albania. I personally justified their harsh behavior. I must have come across the Yugoslav border and both countries were at stake.

I was confronted by an officer sitting in a simple chair and so he let me sit down. Who I was, with whom I had crossed the border, where I had my belongings, these were the first questions of the officer. The worm of their suspicion almost killed me. Of course, I spoke freely. The officer immediately looked at me in amazement. He certainly doubted. It was like a table that was eroding my soul.

“Or brother,” I then addressed the officer, “I have fled Yugoslavia, and everything I say is true.” I myself came to Albania, according to my deep conviction, that this is undoubtedly my homeland. That this is the place where I can be educated and progress, so that one day I will be valuable both for myself and for Albania”.

The officer soon started asking the same questions. One can hardly imagine what stabs me in the middle of my whole being from the top of my hair to my heel. However, thinking that I was at home, I asked for bread to quench my hunger. All day long, the officer kept asking me the same questions. And he always took me seriously. Meanwhile I was saying to myself: you should not be upset boy! This will surely pass, lagging behind my future, which from today has begun to illuminate my little life.

I was tired and fell asleep. When I opened my eyes to my head I saw two soldiers. They told me that we would leave for Shkodra. I was glad that I would finally see Shkodra locen, about which I had heard so many stories. Two soldiers accompanying me led me to the Branch, whose name I had not heard. I realized that it was similar to the Yugoslav militia.

I’m the type who is easily touched. As I faced the Albanian letters, I fainted. I felt sorry for myself because I was upset with what had happened. There in the Branch I was put in a room. At the top is the photo of Enver Hoxha, for whom I had affection at the time. The general of the Albanian army, in those photos shone. U emotion. The officer and manager noticed this and let me sit down.

The first questions and my answers there seemed to me to have been cut by a saw. Then what I had said was read to me, and I signed it. String thoughts eroded me inside. Who was I afraid of? From the officers of my homeland? They were not the Yugoslav militia, de! They were national pride. This officer could not be the one of the militias in Yugoslavia who questioned, beat and drugged my mix.

After signing, I was allowed to rest. A policeman came and as he came down the stairs he handed me over to another and he was checking me the third time I had entered the border. He opened a heavy door and I found myself in the dungeon. I fell asleep there. Only the next day I woke up. To me, as if no one remembered. I knocked hard and asked for bread? It does not belong to you today! – the answer came to me beyond. U korita. I became a beggar. I had to be prudent.

It did not take long and the guard opened the dungeon door. Then ËC FORWARD. The rite of the doors was the same as yesterday. The cops were the same. Po ai police officer. The same questions. The same typewriter. The same expression of indifference and fatigue on the face. Meanwhile, I was hungry. I knew I was as clean as tears and this feeling calmed me down. But their suspicion gave way to my thoughts in a double direction. Do those questions really break my heart? Does my sick cedar touch me?

The next day, on the second day in Shkodra (sadly I could not see Shkodra), they put me in a car and sent me to Shijak, to a house called, ‘The Waiting House’. Here I was at home, I was free and food was provided by those of the police. The second day I was invited for questioning. There in the Shijak police, I had to face the same questions as in Shkodra, although something more detailed. My only preoccupation was not to forget something without saying it and thus it seemed to me as if I was better serving my Albania.

FEVER OF NATIONAL ROMANTICISM

In the Concentration Camp in Çermë-Lushnje, for the first time!

How do you do a long, tiring run and feel the need to relax, to take a long breath? That was my feeling for almost two months in Shijak. It was such that I really breathed freely, even though from time to time I presented myself to the police and the interrogation system, even though the police came to our forced shelter. But this holiday just as I felt, would close soon. And I did not fill them on the road again for two months.

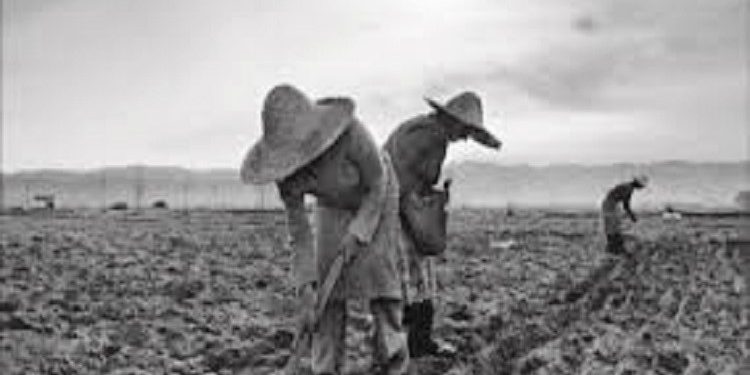

I had taken my thoughts with me. Handcuffed, eyebrow-raised, focused on new visions. The open car left behind smoke. Weak and naked villagers worked in the fields. My relaxation in Shijak had served for something simple. At least he had kept my wild national romanticism afloat. I saw the villagers in that condition and thought they were happy because they were working for a free homeland. No, I was here in vain. When we heard Enver Hoxha’s voice there in Prishtina, we became different and we thought of everything with the account of sublime happiness. And now I was and I was enjoying everything Albanian.

Everything came to my heart, the farmer in the field though emaciated worked on the hills raised like hats that had begun to be stripped of vegetation, the women and girls wearing trousers throwing the seed of bread, were really beautiful though the rinsing of the same had put a mark, the children (eh children) played and sang in Albanian, although badly dressed and worn…

I admired everything and my eyes were wearing the cerge of national admiration. So are my thoughts.

Once the car stopped. The place was called Çermë. We got out of the car with the long shadow of the policeman from behind. One fact surprised me: all the people I met were short, surprisingly incredibly short. In the promenade of Prishtina it was different, tall people, tall. And yet, when you meet only twenty people, you cannot immediately come to such conclusions. Meanwhile, in my retina, those people, even from Çerma, were happily followed.

Skin. Nothing romantic and yet it seemed different to me. Tërbufi used to be there. There are few of them today, from the generations that live, that remember Tërbuf. However, near Tërbuf there was malaria and this, the horror of the musketeers. Because Çerma is Myzeqe and right on the border between Gegëria and Toskëria, not many steps away from Shkumbin. The new transformative hand, was doing something. No one watched the subsequent demolition, what was hidden behind those changes with the socialist name. Near Çermë were the barracks of political prisoners. The barracks were the last evidence of the work of those slaves (I would call them slaves later because I did not see them then) for the drying up of Tërbuf.

Shuaip Hoxhiqi tells me about Çerma, Tërbuf and the barracks. “Do you believe, my friend,” he said with a new half-musky accent, “that prisoners eat each other’s vomit?” Shuaipi, a Kosovar like me, was also convicted there, ostensibly sent by the Yugoslav UDB. I was taking his words with a grain of salt. “People were dying for bread,” he said, however.

Concentration camp similar to that of Hitler, perhaps even blacker. Are you saying that what I heard was true? No, this man did not like Albania, otherwise there is no need to talk nonsense. At times, it seemed to me that Shuaipi was exposing the truth nakedly, and I shook my head violently because I did not want to believe him. Man, or friend, it is difficult to get rid of what he loves, over his life.

What about Shuaipi, how did he turn out? I could not say anything that I knew him in the barracks of Çerma. Maybe it is Shuaip’s fault that deep doubts and despairs arose in me? I cannot say because what he perceived was myself. Eh, Shuaipi, how he never got tired of pointing! Here, the prisoners were put in a cage with thorns, under the open sky, or in the rain, and left there, without the slightest guilt.

In Yugoslavia, I had heard about the treatment of prisoners, about the ruthless beatings of the UDB, but I had not heard anyone tell me about such torture. In fact, I cannot say that I knew everything about Yugoslav prisons. Although I did not trust Shuaip, many dilemmas had arisen in my head. Are you saying that injustices are being done to Albanians in Albania as well?

This suspicion was a nursery raised in my head. A question and so much that I wanted to bury in the dark depths of the subconscious. Almost I continued to be inspired and this condition does not often allow man to get out of his shell. But the power of inspiration is almost as magical as it takes illusions for truth. I now had to let go of illusions and plunge into the bosom of reality.

The skin was nothing more than a concentration camp, albeit without barbed wire! We were over 300 Kosovars. I feel sorry for myself that I am calling them Kosovars and not just Albanians. Their first words were what I wanted when I came here? We have all repented, to find the opportunity even on foot to return. I have in front of my eyes even now: Sokol Jaka, Adem Gega, Hazir Haziri from Drenica. All remorseful, longing, sad. Maybe even those like me had nurtured such a deep romanticism.

Maybe they waited to hold them in the palm of their hand. Most of my compatriots had over 5 years in Çermë. The dream of school was shattered, because there was no school at all in Çermë. Life there was so bleak that it was no longer the light of our conversation. We woke up at five o’clock in the morning, then people were lined up and counted, and then food was sent to work. And what work that. Where did my dreams and, of course, those of my friends go for the unlimited freedom, for the education and for the paradise that existed in Albania?

They melted like dew. And when they dried up, there was no room for dreams in the sun. There in the camp, which left nothing to chance for the Nazi concentration camps, each had a monthly salary of 200 new lek. Not even a man outside the Albanian border can imagine what it means to live on 200 lek per month. I accept it if you cannot go to work, to be stigmatized as a man who does not love popular power. Memorie.al