Memorie.al publishes a report by the well-known Swedish journalist, Sven Aurén, published in the newspaper “Svenska Dagbladet” of Stockholm regarding his four visits to Albania, starting from 1938 when he came for the wedding of King Zog and for him completed in September 1968 where he last visited Enver Hoxha’s communist Albania, after a long odyssey of several years to obtain a visa at the Albanian embassy in Paris, where he joined a group of tourists hiding his identity. From Rinas airport where only one plane a week landed, the counter of the bar at Hotel “Dajti” where only brandy and lemon juice were served, uniformed Albanians who are the only country in the world holding a red booklet by Mao Zed on comedy Dunit / Notes and impressions of the Swedish journalist…

Translated by Adil Bicaku, Stockholm

TOWARDS ALBANIA

The engines roar, the sunlight dances on the wings of the plane, and down in the Adriatic white geese glow. The Italian coast has disappeared behind us. But to the east, high above the horizon rise the blue mountains. What we have ahead of us is Albania: the satellite of China in Europe, the last Stalinist popular republic in the part of our world. Which day of the week? Clearly a Tuesday, because only on Tuesdays you can travel to Albania. As far back as 1968, there is a country in Europe – as large as Belgium – that is far from owning a flight agency and does not even have a passenger plane. It is the Italians who decide on the frequency of traffic. Once a week an Italian company flies on the Rome-Tirana line and always with a half full plane. The same thing happens every Tuesday at Tirana airport, as soon as I get off the flight, I have to hurry to get back again, so my stay at the airport is less than half an hour. This plane, once every seven days, heads for the road to Albania as if it were in the service of transport for food supply of an isolated expedition at the North Pole, constitutes the only connection with Western Europe. But that is also very distant. Although the distance between the Italian and Albanian coasts is only a few miles, measuring it with another meter is endless. Clearly, today’s Albania is one of the most remote countries in the world.

I am on the plane of Tirana, when I write, as a preface, these travel notes. The flight attendants, satisfied that they know they will soon be back in Rome, are generous with both a smile and a drink. Meanwhile they do not need to work hard. The passengers are few: a pair of Italian diplomats, one of whom holds a mail bag to his chest as a parent hugs his child, a bearded man from the Sorbonne who is said to have written a particularly enthusiastic article about national hero Skanderbeg and for this reason it has been officially invited by the Albanian state as well as some Albanians whose status is difficult to determine. Finally, the passenger list contains a collective journey in which I also participate as a tourist among others.

What does a journalist have to do with a travel group? It is not easy to enter the Albanian borders. They are the most closed in Europe, probably all over the world. For many years the benevolent chiefs of the embassy have tried to issue me an individual visa. Applications, phone calls and private conversations, without exception, have all resulted in Albania’s usual response when it comes to visas for hungry Western journalists: – the application is under consideration. Months and years pass, and nothing happens, and over time and this lack of reaction takes on an almost normal character. In the Paris Embassy alone, the unanswered requests of hundreds of journalists are already piled up. But when you recall these events, it is not hard to understand that I was surprised when, by chance, I saw in a window of a simple travel agency, on the Boulevard Opera (Avenue de L’Opera), which was for the Eastern states. In a secret corner, as if it were not the intention to be seen, there was a poster announcing a trip to Albania. The trip was two weeks by bus, a visit to all the cities and large communities … An appropriate question, really just to register, but it was not a matter of departure before the list of participants was approved by the Albanian embassy. That this institution, which had already become the object of so many fruitless efforts, would accept my name in this new case seems of course impossible. But maybe a new passport with data of another profession, then this red robe marked “journalist”, e.g. “Writer”, would not stand out so much?

This happened. And yet, this is the explanation that I am on my way to a communist state, which for so long has refused to accept me. I go with the label as a tour group and that sounds a bit vulgar. But my fellow travelers cannot be considered ordinary tourists. People who want the normal, almost do not go to Albania. In addition, the group is extraordinary in another respect as well. Albanians are the only people in Europe who have Mao’s red booklet on the dresser. It would have been more reasonable for the Sorbonne revolutionary students to seize this opportunity and make contact with a Chinese-inspired nation. Quite strange that there is no young man of that type in our group. Are they afraid that their illusions will fade? There are neither communists nor those with sympathetic communist leanings, who a priori have decided to find the most wonderful one. These are schoolteachers, a young couple specializing in patent applications in the Eastern States, a 78-year-old engineer with his wife, making strange journeys in their remaining lives, and a former judge from Orleans who, is quite blind and is led by his caring wife, who sees for both of them and tells them about everything. He is also a middle-aged man, a postman of general interest from the thirteenth arrondissement of Paris, who has long been angry that he never found anything to read about Albania in the morning bulletin. He decided to take matters into his own hands. It’s mostly a charming French band when they’re fine. But even though in the future it seemed impossible for a journalist to make an individual visit, and a group of travelers, offering the only chance to look inside the borders, you can of course insist that journalism and collective travel have nothing to do with common. In a communist dictatorship of this extreme model it seems that such a journey means that the authorities reveal what they want to reveal and hide others. To take full advantage of at least what I am allowed to see, meanwhile, I have taken a number of preparatory measures. There are diplomats from different countries, who have recently been stationed in Tirana as well as specialists, who have had various services in Albania. Thanks to informants of this type I am armed with prior knowledge of the current situation. With this there are several possibilities to compare between the present and the past.

This is my fourth trip to Albania. … On revienz toujours (* Another trip, French)

At a young age I met an Albanian student in Paris and then spent a week at his home in Tirana. The visit left such a strong impression on me that a few years later I went again to write a book about the country. The third visit I made shortly before the war was when I traveled by car from Stockholm to attend King Zog’s picturesque wedding to Hungarian Princess Aponyi (Apponyi). This was in April 1938. Immediately after a year, the Albanian state disappeared from the waves of war, was deserted, fragmented and finally returned to its current form.

To this Albania of yesterday that I paid so much interest to, was an unknown and primitive Balkan nation with a million inhabitants, which always calls itself Albanian: the sons of eagles. With over two-thirds unproductive mountains and nearly a third of cultivation in valleys and coastal belts, which is also a very poor country. Throughout its history it has been on the path of great conflicts of interest of the great powers. That the Albanians, who are the descendants of the Illyrians, were able to preserve both their own language and national features – e.g. living habits even physiognomy- is a miracle! Directly or indirectly they have always been colonized. They were ruled by the Greeks, Romans and Byzantines. For five centuries until 1912 the land was Turkish property. During World War I it served as a battlefield for superpower armies. In the 1920s for the first time it gained, at least it seemed, a form of political independence. The social structure was feudal with a number of wealthy highland leaders as dominant figures. In 1928 the mountain leader Ahmed Zogu was able to persuade other strong leaders to accept the formation of a monarchy where he was proclaimed king named Zogu I.

The permanent tragedy of the country is that it has never been able to survive without a foreign financier. Zog ruled but Mussolini paid, which turned the country’s first king into an Italian vassal. In 1939 the vassal was not so obedient so he was expelled, and the country turned into an Italian colony. But during my visit in the 1930s there was still the untouched throne set in a parlor in the royal palace in Tirana, which looked like an average Djursholm villa (Djursholm) * A villa neighborhood on the outskirts of Stockholm. The rich class lives. (transl. note)

When you are sitting like this in an airplane seat on the way to a new Albania, the knowledge of which is only of a theoretical nature, it is natural for the past to come to mind as a show. Is there anything left of the fascinating Balkan state? But the magnificent landscape of the country must have remained as well:

Adventure mountains, winding roads, those deep blue lakes in Shkodra and Pogradec, stone bridges bent like angry cats on the slope of gorges, eagles, flying around the ridges of massive mountains, those green valleys with their flower fields sun, tobacco and corn … But people, atmosphere? Before the war, travelers to Albania were quite small and, in their countries, they were considered extravagant, romantic or adventurous. In Albania they were kings. They were welcomed as honored friends. The rich and the poor competed to open the doors, they shone with pleasure, the readiness was total. Generosity was elevated to religious dogma. At one time, it even happened that the blood feud was left aside, which was painful, and that devastated the country like cholera and led to the extinction of both families and tribes. If the victim, who was to be killed, managed to enter the enemy’s house before he could shoot him, he took advantage of the habit of hospitality as long as he stayed there.

Albanians liked to photograph them and wanted to give gifts. They gave us fishes wherever we went. Fukaren people – most of them were almost fukaren’s unimaginable – they behaved with a dignified great pride. The zealots roamed the village streets like princes. In terms of colors it seemed that the picture was sublime. I remember the Shkodra market on an April morning: Highlanders in white sheepskin clothes, black sleeveless jackets and oval hats on their heads, women with straight black ponytails and laborious clothes, to bring the Eskimos to their senses. Greonlandës. Women from Malësia with oily hair and fringe on the forehead and a strange belt with pafts, capraze, serme nizamçe and tin rivets …. This Albanian carnival, which was not a carnival except for an ordinary colorful day, would fascinate a clothing historian. You can see such scenes in other places in the Balkans, but in no other country were they as intense and fantastic as in Shkodra. It depended on the isolation of a small state, which Europe had completely forgotten.

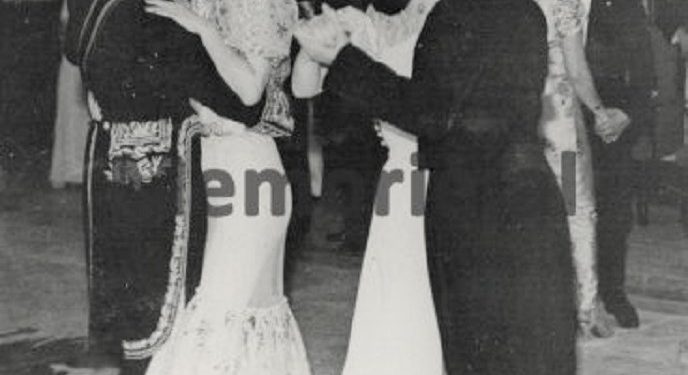

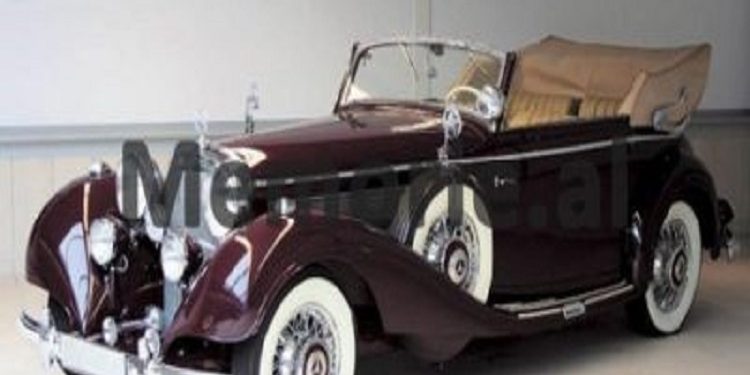

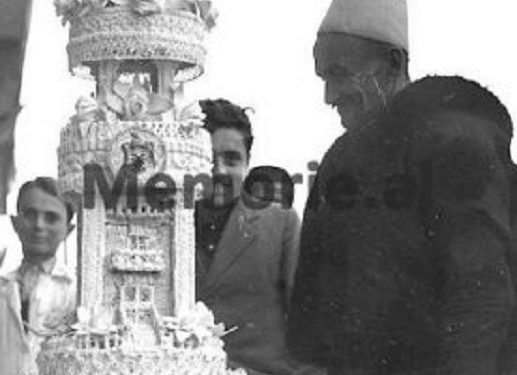

Even King Zog, who never wanted to be called “King of Albania”, insisted on being called “King of the Albanians” thinking of the Albanian minorities in Greece and Yugoslavia. I see him, on his wedding night at the palace in Tirana: a Buster Keaton * American artist 1895-1966. (note) Albanian with a stiff face without emotions, and covered with decorations so that the shining star hangs down to the bottom of the hood of the uniform. Next to this knight with serious looks a tall, beautiful tall girl who looks extremely excited to have become queen though in an operetta Monarchy. Behind the couple an inflated Italian in a fascist uniform with his chest forward and a smug smile on his healthy face: Mussolini’s son-in-law, Count Ciano. The count was the godfather of the marriage. No one could have imagined what fate awaited them. This godmother would return with an invading army and force the royal couple into exile, and he himself, after a few years, would sit in a chair at an execution site in northern Italy and be shot in the back as a traitor. The atmosphere was great, even though there were some owls like e.g. the French minister, who could not contain himself and laughed out loud when he saw the wedding gifts: six saddle horses from the Hungarian state, a motorboat from the Duce (Il Duce) and a Mercedes from Hitler. “The donors seem to have had the same thought in their heads: Better to give them something to serve them in case they are forced to leave the country.” The dance began with the tunes of the Royal Court Orchestra and an orchestra brought by the bride from Budapest. Diplomatic representatives from twenty nations danced waltzes with the ladies of the Albanian aristocracy, while the walls were surrounded by mountain leaders dressed in national costumes embroidered with gold and with belt pistols. Some of them completed the pistols with a gold fountain pen which at the time meant that the person in question knew how to write. The tops of the minarets were decorated with floodlights and decorative strings. Large balloons with the portrait of the royal couple were brought on the roofs of the houses and at the airport of Tirana they threw excellent fireworks of the best Italian brand.

Tirana Airport … We are already there. Fasten your seat belt, turn off your cigarettes, signores et signorinas. The capital of Albania lies inside a mountain cauldron. The plane sinks down to the bottom and touches the ground. It was on the eve of Zog’s wedding when I saw this airport last time. Then there were a host of cheerful people admiring rockets and fireworks in the sky. At that time no airport was seen except people. What about now? I look around through the open door. It is now deserted like an abandoned square for emergency discounts. No aircraft other than tuna. No man except a melancholy soldier, who is leaning on his rifle. No building except a kiosk-like house crowned with a red star.

Albania in September 1968

LIFE IN TIRANA

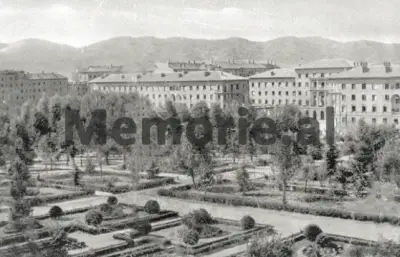

The best hotel in Tirana and Albania is called “Dajti” after the name of one of the highest mountains around those that surround the capital. The building from the outside is something magnificent, separated from the wide boulevard by a pine curtain. But it was not the Albanians who built it, but the Italians. The latter did surprisingly much, in the short time as gentlemen of the country. The entrance hall is very large, marbled and very formal, nice rooms, hygiene leaves much to be desired. The elevator – the only hotel in Albania with an elevator – is out of use, but cleaners in black dresses, white aprons and bun hair, carry guest luggage down the stairs while the staff men watch. The Turkish occupation that lasted 500 years has left traces to this day. Hotel “Dajti” is reserved for foreigners, while the locals have it banned. Albanians, who are sitting in the hall or leaning on the sad grass, are plainclothes policemen and you cannot read anything on their faces. The atmosphere is generally heavy and characterizes the People’s Republic as a whole. The goalkeeper greets the new guests without any attempt at a smile, not even noticing a gleam in the servant’s eyes. The bar waiter, a middle-aged man looks like he buried someone close this morning, and on the shelf a row of urn-like bottles in a columbarium * Shelf where urns are stored with the ashes of the dead. St. Trans). They serve only as decor. You cannot order drinks respectively (whiskey, cognac, sherry, etc.), except that customers are forced to choose brandy or lemon juice. And with a glass of brandy in front – the best Albanian brandy, which is said to be made from berries – if you browse some brochures, which are accompanied by the key to the room. Advertising for the hotel? Tourist propaganda for Albania? Nothing. One speaks of “Russia’s betrayal of communism” and the other calls on the socialist world to be vigilant: “Capitalist elites are rising up in Czechoslovakia.”

I turn my back on this happy grass … and set off for the city with the beautiful name. What a traveler in Tirana finds out, who before the war, when he left the hotel, was the noise of the street.

Taxis and private cars were blown incessantly, but there was another type of traffic noise: a large majority of horse-drawn carriages, which had been fitted with car horns, and the carriages fell as hard as motorists, a multitude of donkeys used for transportation. and contributed to the great roar of the concert, chariots and carts, various, four-wheeled, street vendors, ringing bells, street musicians … Besides, the bad motor roads made the cacophony reach its maximum. The noise may have made an irritating impression, but at the same time it reflected a happy life in a capital, which was a very large Balkan village.

What man encounters now, silence. It is strange and unimaginable. Hotel “Dajti” is located on the main street, which during the Italian occupation was re-baptized from Boulevard Zog to Boulevard Mussolini and is now called Boulevard “Stalin”. It is as wide as the Chams-Elysées * Grand Boulevard in central Paris. (note for). and quite well maintained: no debris, asphalt shines like a mirror. On one side stands a monument depicting Stalin, on the opposite side Lenin appears, otherwise the boulevard is surrounded by new and quite pompous houses, combined with parks. Far away a large space, round square where the national hero of Albania Skanderbeg with his famous helmet controls the situation of a bronze horse with its first legs in the air. You cannot deny that Tirana is decorated. But if in the bar of Hotel “Dajti” there is an atmosphere like in a tomb room, in “Stalin” Boulevard the true tranquility of the cemetery prevails. I do not exaggerate. Silence is related to the traffic situation or to put it bluntly the lack of traffic. The boulevard is empty: neither cars, carts, chariots or donkeys and almost no people. It was a day of the week from four o’clock in the afternoon that I noticed for the first time. A woman was pushing a pram in the middle of the sidewalk where some children were playing without clothes, and a single man was standing still and reading “Zeri i Popullit” which is the “Pravda” of Albania. As a tourist in the Sahara, I waited a long time for a car to appear, and finally I could see a truck and an elegant “Mercedes” with white curtains closed, hiding behind a high-ranking communist official. No motorcycles, a couple of bikes.

Another experience awaits in “Skënderbej” square. A policeman with a white rubber baton was serving in the square. He is the only traffic policeman in Albania, and this desolate one has nothing to direct. I feel the need to help him as much as Chesterton * (Chesterton) Gilbert K. Chesterton 1874-1936 British writer and poet. (ref. note). shows how an English tourist helped a German railway bill, which seemed very melancholy. By buying a ticket to the nearest neighborhood and giving it to him to wait for, he made the desperate clerk rejoice.

An advertisement in the hotel says there are rental bicycles. If I had followed the news of the proclamation, and passed through Skanderbeg Square by bicycle, I too would have done a good human deed. It’s easy to ironize, but the lack of traffic has a natural explanation in itself. Red Albania is a nation in poverty, which lacks almost everything and especially foreign currencies. Cars, motorcycles and bicycles are not produced in the country and must be bought from abroad and paid in other money and not Lek, which is the Albanian currency. In this situation enjoy, buy the necessary machinery, i.e. buses and trucks (plus some cars for the gentlemen of the country) and restricting the import of bicycles to a minimum. Wheelchairs, carts and donkeys, meanwhile, are considered to have a backwardness and are banned in the center of the capital for prestige reasons. The result: emptiness and silence.

The communist broom has wiped out many other things. Many constructions have been done in Tirana during the last 20 years, and new modern residential areas have been set up. The clutter of alleys and paths on the outskirts of Skanderbeg Square is almost the same as before. But all that gave the city those colors and that allure is gone: the innumerable small shops and the neat ones who stood outside them and smoked with long-worked well-worked pipe, the covered women, who squatted near the walls, the villagers, with their rare costumes, coming from the high mountains, the desert rags, and the proud bayraktars with beautiful horses, swarms of begging children, the sweet aroma of Turkish coffee, which spread from hundreds of small cafes ….. All Tirana carried the aroma of coffee at that time. Now the city has no fragrance. All men look the same: men are dressed in dark pants and white shirts and women wear cotton dresses, but it must be said that according to the clothes it does not seem that there is pronounced poverty. Man is no longer even followed by the crowd of begging children. Not because children are missing. On the contrary. In today’s Albania, fertility is promoted in all ways, and thanks to this policy, the population has increased from one million to one and a half since the war. The capital has 135,000 inhabitants compared to 35,000 in 1945. You see children everywhere as well as pregnant women. With red scarves around their necks, and red flags in front of the line in the form of military units, young people march, singing anti-imperialist songs, and are called “Red Pioneers”. /Memorie.al

Continues tomorrow

![“After the ’90s, when I was Chief of Personnel at the Berat Police Station, my colleague I.S. told me how they had once eavesdropped on me at the Malinati spring, where I had said about Enver [Hoxha]…”/ The testimony of the former political prisoner.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)