Dashnor Kaloçi

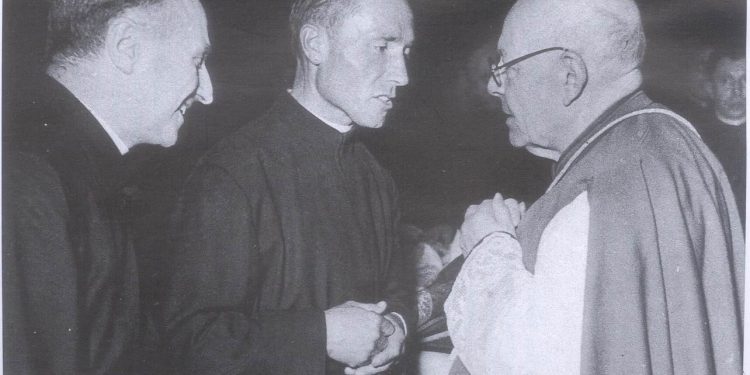

Memorie.al the unknown testimonies of Father Jak Gardin, the Italian clergyman who came to Albania in the 1930s serving as a priest in some of the parishes of the Northern Highlands, and a lecturer at the College of Jesuit Frents in the city of Shkodra. The whole story from his arrest by the communists in 1945, the sentence of 10 years in prison on charges of “Vatican agent”, the ordeal in camps and prisons, repatriation to Italy in 1956, after the Khrushchev-Adenauer agreement, publication in Rome in 1992 of the memoir, “Ten years in prison in Albania 1945-1955”, until his arrival in Albania after the ’90s….

One of those foreign nationals who suffered for a long time in the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, was also the Italian Catholic clergyman, Father Jak Gardini, who had come to Albania since the 1930s, to serve as a parish priest in some from the remote areas of the Northern Highlands and as a lecturer at the Jesus College in the city of Shkodra. But his dream of continuing his devotional service to Albania’s Catholic faithful was cut short in 1945, when he was arrested by the new communists in power. Following allegations made as a “Vatican agent”, Father Jak Gardini was sentenced to ten years in prison, which he suffered in forced labor camps in several districts of communist Albania. He could only be released from prison in 1955, and that same year he was repatriated to his native Italy. In the early 1980s, Father Jak Gardini wrote memoirs of his life, of the time he had served in Albania, and of serving his sentence, summarizing them in a book entitled “Ten years in prison in Albania” (1945 -1955) which was published in Rome on May 24, 1986. From that book by Gardiner, we have selected only a few parts, which we are publishing, presenting them in the Gheg dialect, as written by the author himself.

Father Gardiner Memoirs: My Arrest in 1945

It was night when they came to arrest me. Surrounded by soldiers, after a short walk, I was taken to a private apartment, returned to military command. They pushed me into a large dark room, where I could hear you snoring on the beds and exploding, squealing with the slightest movement. I lay down on the ground, wrapped my priestly belt around my waist and put it under my head like a pad, and after leaving my fate in the hands of God, I tried to sleep. But then an army of insects, fleas and bugs, filled me and tortured me until three in the morning. When the guard officer remembered about this condition, he pushed me out of pity, removed me from there, and after laying his coat on a metal net above the floor, left me to get some sleep. The next day I was transferred to one of the many prisons, open to the public in the city of Shkodra. It was rumored that there were some thirty prisons, all full. There I realized that a new and different phase of my life was about to begin: the life of a prisoner, and in what hands?! And so, began the sleep on the ground, the torment of insects, the anxiety of questions, the howling of the tortured, the endless squeezing of one’s conscience to discover innocent guilt, loneliness, threats, insults, scandal, trying to uncover a secret. of prisoners for trials and sentences and shootings. It was an end to hell for him to long for death as a deliverance, to the temptation of suicide if handcuffs had allowed it. Food ration: bread and water; wheat bread and wood water, as it was said among us prisoners, except that the bread was mostly corn bread, cooked as if not worse. It was a whirlwind of monstrous things ragged in my subconscious tue conceived, horrible load turned into forge of waking dreams, nightmares. Even after twenty-five or thirty years, sometimes I wake up suddenly, terrified, and it seems to me that my heart is pounding. That first prison was a large room with different windows and doors. On the floor were the remains of the one who had been before me, the filth everywhere, and the containers filled with human outcrops. In a less filthy corner, they gathered in silence, as if they wanted to consider what the future might hold, and then to hear from their peers the whispered stories of torture they suffered during the interrogation. I remember that among them was a German soldier, he was suffering from sprains, and we tried to knock on the door of the cell, but only in the evening and in the evening was it allowed to go and empty the dishes full of dirt. In our room the dishes were also full. When the guards, annoyed by the persistence, set the door open, they usually emptied a battery of kicks on the unfortunate one who was patient enough to do the need. In those anxious states, I spent all my time thinking about myself, never in my life did I examine my conscience so closely. I convinced myself that “my sins” were not guilty of imprisonment. They were limited to a word that every priest should say in the performance of his duty, no matter how unacceptable to the one who master atheism. But how unhappy we were! I still did not realize that my guards were less interested in the truth or innocence of me and others. The aim was to eradicate from Albania, one after the other, people and institutes that in any way had to do with the religion of the Catholic Church, thus eliminating the possibility of any ideological and political opposition. I was convinced when they started questioning me too. I was completely isolated. I found myself only before my conscience, with God, before whom I feel innocent, but also with my wicked body. During those endless days and nights, I experienced some of what must have been the night of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane. I was completely alone, without comfort, among hostile people, defenseless at the sight of suffering and perhaps death. Tenzo’s angel really comforted my heart as soon as my body shook and sweat covered me. When it was my turn, the cell door opened. A guard ordered me in a rude tone: “Chou”! He grabbed me by the arms, led me by the irons, and led me through several streets of an office where an officer was waiting for me. He accepted me with obvious warmth and noticed me with a long curious look: I was wearing frock! He told me to get up and there he started the interrogation. But before telling you about the development of the questions, I think it is appropriate to say something about what had happened before my arrest.

Why was I arrested?

Towards the middle of the school year 1945, the director of the college run by the Jesuits in Shkodra was informed that the military authorities, who had taken power in the country, wanted to create a communist youth cell by the students of the high school and the Lyceum. You have no choice but to humble yourself! So, every week, a propagandist came to the college to teach me his lessons. One of the professors in turn was present at the conference to be close to the students and to get acquainted with what is being taught. Towards the end of May, he also met me to attend one of these conferences. Berlin had just come under pressure from the Red Army. The conference enthusiastically praised the definitive victory of communism over Nazism and fascism, and delved into the description of the evils that these ideologies had caused to miserable humanity. He was right, but at the same time he placed himself on the same level and charged the German and Italian nations with the same responsibilities. I heard them silent, and when at the end the conference invited the attendees to give a personal contribution on the presentation of the topic, I got up and asked for the floor. “I am Italian,” I said, “and I am not interested in Nazism.” As for qi fascism leading Italy to its present destruction, I must point out that I do not consider it right to equate the Italian nation with the qi party that has ruled it in recent years. “Also, it does not seem to me a good historical method, to claim that fascism has only done bad things and to deny the merits of the Italians in those cases of cooperation, where the initiatives of fascism have turned out positive”. I listed a number of bad qi, according to my judgment, fascism has caused to the Italians, even some bad qi on the contrary thought positive. Among other things, I claimed that Mussolini could be credited with resolving the ancient Roman issue. My intervention left the conference more or less confused, she answered some questions and hurried to finish. I accompanied him to the exit and congratulated him on his conference, but at the same time I noticed that he was very angry. To him my remarks were a “sabotage”. He immediately filed a lawsuit against the Prosecutor, so severe that he did not allow me any punishment other than a bullet in the forehead. I learned the details of that indictment later, from the Prosecutor of the Republic, who, during an interrogation, could not understand how I could admit my innocence in the face of the attacks, like those who were listed in the indictment. The suspicions on me weighed as heavily as a storm, when, a few weeks later (June 21, 1945), we celebrated the feast of St. Louis Gonzaga in college. At the solemn Mass, in the presence of all the students, I raised the figure of Satan who had stretched his energies into the spiritual sources of his faith in God. Some civilian agents, present at the mass, took quite a few notes of my words. Were they held as an insult against Marxist-Leninist ideology? Did they call them a pro-regime move? I could never have known. But about 9 o’clock in the evening, a group of armed men came and took me out of the house, and from that moment on I did not return among my brothers. During the twenty days that passed between the first and the second, the above-mentioned episode, a quantity of material was accumulated against me. But it was not my activity that weighed on the scales, in the trial of lawsuits you will be brought the whole process of punishment. On the other hand, in my conscience before God I find no reason to rebuke myself during the ten years of being completely committed to the good of the Albanian youth.

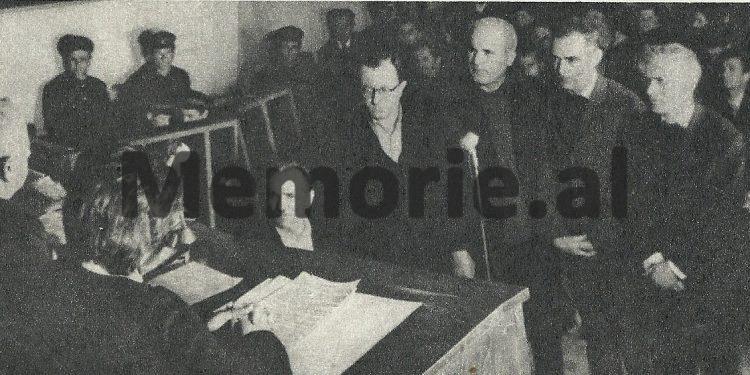

Trial of Father Gardin

During the questions I showed the feeling of the most complete sincerity, maybe someone could even tell me that we were almost naive, my interlocutor, on the contrary, was completely convinced that he was dealing with “a Vatican spy”. Question after question, you suddenly changed the conversation, the prosecutor twisted it in a hundred other ways, entered surprising details and connected them with banal expressions. It was confusing and calming who knows how many times. Finally, with insidious phrases, I was threatened that he would shoot me in such a way that I would be forced to ask for it as a great honor if a rifle fell on my forehead. Before these threats, my tongue escaped me and I said: “If you dare to cause me only an unjust torture, someone will surely come out and hold you accountable, and you will pay for it.” He was stunned and whispered: “We will see you again”, and handed me over to the guards. In fact, I have never been an expert in politics. I am always interested in events; you value them as they seemed best to me based on personal criteria. But the suspicions, the foxes, the cunning with the crimes that often accompany them have never interfered in my sphere of interest. On the contrary I have always hated them. Maybe this is evident from my behavior, my way of reasoning and my defense. The fact is that neither this officer, nor the other qi who interrogated me later and consequently neither the prosecutor himself managed to uncover an accurate lawsuit against me that could reasonably be presented as guilt. But I was a priest so you have to give a sentence. In case the lawsuits were unstable, they should be dressed in the guise of crime! Even before my conviction, and for the reasons that the Albanian regime never announced to the public, towards the end of ’44 or the beginning of ’45, when he was shot in Sheldi, Dom Ndre Zadeja, a scholar in Za, in his parish in the districts of Shkodra. Around the same time in Tirana, Dom Lazër Shantoja was shot, after terrible tortures. Also, in Tirana in the first months of 1946, the Franciscan, Father Anton Harapi, was shot dead, along with a number of state ministers, because he had been part of the government imposed by the German occupation forces. And in 1944 the priest Alfons Tracki had died in hemp, for the only fault that he belonged to the German nation. But when he returned to my trial, he reminded me that around the middle of August 1945, the so-called “People’s Court” began to function. Until then, the process was going on, as it were, behind closed doors, but the people were only invited to be there in the death sentences imposed quickly. It was the period in which the punishment should be applied as soon as possible against all the “criminals and traitors”. Often at dawn the light of machine gun fire was heard and then the last bullets. Later, the names of those shot were announced on the city walls. That was the end of their fate.

Hundreds of foreign nationals suffered in Albanian prisons

Some were released from the Khrushchev-Adenauer agreement, others suffered long

Throughout the period of the rule of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, starting from December 1944, when the communists came to power, until the end of the ’80s, in the prisons of communist Albania have served long sentences many citizens of foreigners, such as: Italians, Germans, Greeks, Serbs, Montenegrins, Jews, Macedonians, Romanians, Bulgarians, Poles, etc. With a few exceptions, all of them were convicted by the courts of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, being charged with political offenses, as “agents of foreign services” and other accusations fabricated by various. In the mid-1950s, following the Hurshov-Adenauer agreement, which included the exchange of prisoners of war in several Eastern European countries, some foreign nationals serving sentences were long in the prisons of communist Albania, took advantage of this agreement and were released from prisons. Most of them after that, benefited from repatriation, leaving Albania for their countries. But even after this agreement, in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, many foreign nationals remained, who were forced to work the hardest jobs in the forced labor camps that were then located in almost all districts of the country. Most of them died in prisons without enjoying freedom, and only a few of them were able to escape alive from the communist hell where they had spent years. One of them was Father Giacomo Gardini, the Italian priest who after repatriation to Italy in 1956, a few years later wrote his memoirs and published them in 1992, in the book entitled “Ten years in Albanian prisons 1945-1955”, part of which we are publishing in this article.

The tragic story of the Italian Jesuit clergyman who also served as a lecturer at the Jesus College of the city of Shkodra

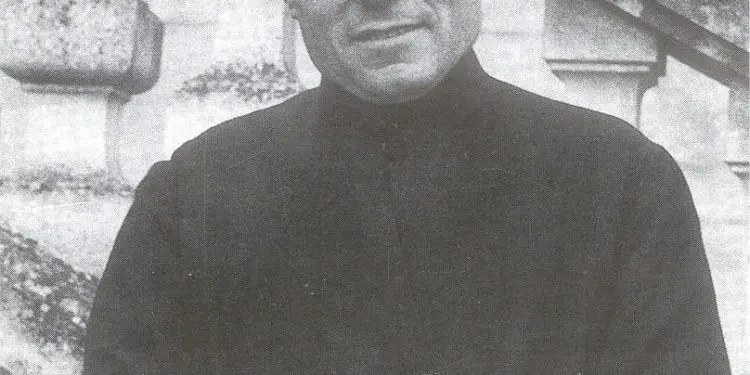

Who was Father Giacomo Gardini?

Giacomo, or Jak Gardini as he was known in Albania, was born on September 24, 1905 in Prodolone, in the province of San Vito Tagliamento in Italy. When he was 18 years old, on November 12, 1923, he entered the Society of Jesus, and after two years of novice studies in Gorica, he was prepared for several more years in Philosophy. After that, Giacomo moved to Chieri (Turin) in order to attend three-year Philosophy courses, according to Jesuit tradition. After completing the entire cycle of Jesuit studies, in 1930 he transferred and came to Albania to serve in the ranks of the Catholic Clergy. At that time, he was appointed as a lecturer at the College of Jesuit Fretans in the city of Shkodra, where for many years in addition to the Italian language, he taught several other subjects of general education. In addition to teaching, Jak Gardini also dealt with the collection of folklore, docks and customs of Northern Albania. In 1936, he returned to Italy to pursue theological studies, and upon their completion, on July 15, 1936, he was ordained a priest in the province of Chier by Cardinal Maurilio Fossati. Then, in the years 1937-1938, he went to France to spend a year in Paray-le Monial, where he completed the last year of the long cycle of studies of the Jesuit Society, which was considered the third year of probation. Immediately after completing those studies in France, he was appointed to come to Albania as a lecturer at the College of St. Francesc Saver and at the Papnuer Albanian Seminary in the city of Shkodra. From that time until 1945, Father Jak Gardini, who was fluent in the Albanian language, taught at that College, devoting himself with all his physical and spiritual abilities to the education of the youth. In 1945, when Enver Hoxha’s communist regime launched a brutal crackdown on the Catholic clergy, Father Jak Gardini was arrested on charges of being a servant of fascism and a Vatican agent. After being held for some time in the makeshift prisons of the city of Shkodra, he was brought to trial and sentenced to 10 years in political prison, which he suffered in several forced labor camps that were then everywhere in Albania. In 1955, when the communist regime in Tirana was improving diplomatic relations with Italy, and after the famous Khrushchev-Adenauer agreement, Gardini was released from prison and repatriated to his country of origin. After spending a short time in a religious institution called the House of Spiritual Exercises in Bassano del Grappa, he was entrusted with the spiritual direction of the Jesuit students of Lonigo (Vicenza) where he served until 1960. In that year the Gardini was sent as a superior to the Rivalta Exercise House near Reggio-Emilia. From 1964 to 1976, he served in the city of Trieste as a Jesuit superior and as a parish priest. While in 1976 he continued to perform the duty of priest in Parma, Italy. Although he had suffered for 10 years in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, Father Gardini did not confuse him with the Albanian people, whom he had served devoutly for years. Based on this fact, with the fall of the communist regime in Tirana, he immediately came to Albania, giving his help in the rebirth of the Catholic Church and the freedom of religion. Father Jak Gardini passed away in 1996 at the age of 89. /Memorie.al

Continues tomorrow