By Adrian CIVICI

When did you start talking openly about the “market” and the “market economy in Albania”? How did we as economists formed with centralized planning and state property with the free market, the capitalist west and the debates of various economic schools on these new concepts at the beginning of the radical transition “from the market plan” in 1991?

The market and the market economy in Albania, mainly in the university and intellectual environments, began to be talked about openly, or to some extent openly, in the years 1986-1990.

More than “concepts of the free market” and “market economy”, there was talk of economic theories arguing or legitimizing the best economic policies in a non-socialist economy, there was talk of the “political economy of capitalism” and economists like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Maynard Keynes, Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, John Galbraith or Douglass North, spoke of the American economy and Western European countries that had secured all their development and prosperity thanks to the market economy and capitalism, and so on.

At that time, books on macroeconomics, microeconomics, financial markets, various Western economic newspapers and magazines, mainly British, Italian and American, etc., had begun to enter Albania “secretly”.

What was our idea, knowledge or definition of the market and market economy in those years? Hard to say that we had any clear and structured ideas, other than the belief that it was something quite the opposite and different from the centralized and planned economy.

During the university years, and later in the period 1982-1990, the opportunities to read books or magazines that talked about market economy or capitalism, we had very limited.

There were very few “Western” books in the libraries dedicated to this issue, because they were considered books banned by the socialist regime and were not allowed to enter Albania.

In addition, the opportunities to read were extremely limited. Such books required “special authorization” from librarians, which was given only to those who “needed to read such books as they had to sharply criticize the capitalist system and the savage exploitation of the working class in bourgeois countries.” revisionists ”, or those who“ had a good biography ”and served the Party and Comrade Enver diligently.

The rest of us, be they university professors, intellectuals, researchers, specialists and experts in various fields, etc., used all sorts of ways to find opportunities to see or read such “forbidden” literature.

We formed special friendships with individuals who could lend us these books or magazines, found “friends” or “family ties” with library staff who allowed us to see banned books, entered bookstore rooms ostensibly for find an old book or newspaper, locked us up in library offices for a few hours to read these kinds of books, gave us wrapped in newspapers or other covers for only 24 hours to read at home, and so on.

Everything was difficult and dangerous, especially since the ALP and the high political caste of the country declared that “in the economic sphere, the socialist model was more advanced and more humane than the capitalist one, so the Albanian scholars and intellectuals had none need to read economic books of revisionist bourgeois countries “,” on the contrary, economists and politicians of capitalist and revisionist countries should read the works of Enver Hoxha on economics, in order to study them and recognize the spectacular results of economic and social development of socialist Albania “to have the opportunity to improve life in their countries.”

My first “real” encounter with understanding and explaining the market and the market economy took place in March 1991, when the Republika newspaper, the newly formed Republican Party newspaper, asked me to write a long explanatory and polemical article dedicated to its primary objective was “the total failure of the socialist economy and the half-baked reforms of the albanian communist government and President Ramiz Alia, and the establishment of a free market and market economy in Albania”.

This was probably the first complete article on economic reforms and market economy to be published in Albania. I tried for about three or four weeks to read as much as I could from the foreign literature dealing with this problem, especially the experience of some other Central and Eastern European countries that had already started this process, and on all platforms and analyzes of several international institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank in this regard.

At their core, my knowledge of capitalism and the free market, at the time, was somewhat deficient and fragmented. Everything was summarized in a set of knowledge and market elements such as “a place where goods and services are freely exchanged”, where “prices are free and determined by the supply-demand balance”, “where there is no centralized planning, but operated in conditions of economic freedom ”,“ where the State is only one of the market players ”,“ where money has a role completely different from its role in the centralized economy ”, etc.

Uncertainties about the market and its functioning in a capitalist economy added to me even more and from a seemingly humorous moment, but in reality, very painful and challenging. In the first months of 1991, I attended several open macroeconomics lectures given by some American professors in Tirana.

After talking for about an hour about the market and its institutions in capitalist economies, the American lecturer was faced with a series of questions that were as strange as they were naive. I remember his answer today: “You are right that you are confused and unclear, because while I am talking and explaining the market, you all have in mind the market”.

Meanwhile, in the headquarters of the Democratic Party in “Kavaja Street” were organized several sessions of talks and lectures on “market economy and capitalism” during which they distributed some books, dedicated mainly to micro and macroeconomics, banks and financial markets, etc. These were my first “serious” contacts with new concepts of free market and market economy.

But all this “knowledge” of the free market was still scarce to take on an accurate and valuable article, all the more so in a newspaper representing a typically right-wing Party.

A colleague of mine, a lecturer at the Faculty of Economics in Tirana, who had been a student of Gramoz Pashko, probably the only lecturer at this faculty who had for years spoken and discussed openly with his students about various economic theories, market, capitalism, Smith- in, Hayek, Keynes, democracy, recommended me to read four important things before trying to form a consolidated view of the free market and capitalism: the idea of the market in classical political economy, the neoclassical market theory, the core of the IMF and World Bank reforms in Latin America in the 1980s, and the basic market concepts in “development economics” theory.

The American Embassy in Tirana came to our aid, which organized several meetings with economists and economics professors of several universities, to talk to us about capitalism, market economy, transition reforms and the role of international institutions in this process.

In these meetings that were organized in the offices of the Democratic Party in Kavaja Street, the participants were given some books on economic and financial policies in the US, Macro and Microeconomics, etc. In those first months of the transition, on many shelves in libraries or various offices of university administration, find these books distributed by the US Embassy and the DP.

Other books I found and could read in those months were: “Les grands courants de la pensée économique” by Alain Samuelson, “The New Classical Macroeconomics” by Kevin D. Hoover, and “Lectures on Macroeconomics” by Olivier Jean Blanchard and Stanley Fisher. I was entering a world of knowledge and concepts almost completely unknown and quite complicated for an economist formatted with Marxist theses and harsh critique of economics and the capitalist system.

Referring to classical political economy, I began to theoretically consolidate the first ideas: the market is the place of exchange of goods and services where their exchange value is formed… the market is the place where the price of goods is “read”, their prices are formed freely … The market is the place where capital is valued… it is the place where the interests of economic actors are most optimally met… in the market money has only the role of a “sail” with influence only in fixing the general price level… the market is mainly national… the market is self-regulating according to the concept of the “invisible hand” e State intervention in the economy should be minimal…. Profits in trade derive from comparative advantages. Smith theory of absolute advantages, etc.

Meanwhile, according to neoclassical theory, the market vision I encountered was completely transformed. Beyond the change in the explanation of value formation, the market was explained as the place where economic actors met “continuously and endlessly” within the supply-demand mechanism and reaching equilibrium price; the market was the place where contracts, advantages, preferences, restrictions, etc. were negotiated and renegotiated, until “general equilibrium” was reached; the market gives its main signals through prices; the market is the place of the socialism of the individual, the place that connects the individual with society; the task of the State is only to “correct market deviations or imperfections”, while the State itself is simply one of the market actors; the most preferred economic policy of neoclassical theory was the one based on the “laissez-faire” philosophy; etc.

The third “confrontation” with the market economy came from reading the articles of American economist Jeffrey Sachs, author of “choc therapy” as the most effective solution to economic crises in some Latin American countries, Poland and Russia, as well as some analyzes dedicated to the “structural adjustment programs” and the “Washington Consensus” of the IMF and the World Bank implemented in some Latin American countries during the 1980s, programs that were understood in 1991, would be implemented in European countries as well. central and eastern, including Albania.

This situation was further reinforced by the debates and controversies caused by the statement of Gramoz Pashko, one of the main leaders of the Democratic Party, who had just arrived from an “enthusiastic” visit to the United States, at a PD rally in Berat in March 1991 that “We received a guarantee that, if the DP wins the elections, Albania will be given a white check.”

Of course, this was a misunderstood and misinterpreted metaphor, but at its core, it meant whether Albania would make the reforms suggested by the IMF and the World Bank in the framework of the “Structural Adjustment Programs” (PAS) aimed at expanding the doctrine. liberal even in the former socialist countries of central and eastern Europe, the albanian economy could benefit from colossal western investments.

During 1991, Albania was getting ready to negotiate a special agreement with the IMF and the World Bank to start the transition process “from centralized planning to free market”, an agreement to implement a series of fundamental reforms under the motto stabilization-liberalization-privatization , which were based on: restoring macroeconomic balances, reducing the government budget deficit, free circulation of currencies, liberalization of trade and removal of customs barriers, elimination of price control, elimination of subsidies, especially those of the public sector , massive privatizations of the state sector of the economy, the establishment of a legal and institutional framework to guarantee property rights, the reduction of the state presence in the market and the economy, the creation of an independent central bank, etc.

The fall of the “Berlin Wall” and the end of the 10th century faced Albania and all other former socialist countries with a new historical phenomenon: the transition from a planned and centralized economy to a market economy. Although some partial attempts at this route had taken place before – Yugoslavia in the 1960s and 1980s, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and to some extent Poland in the 1960s and 1970s – the new route seemed full. unknown.

A well-known expression of the Russian economist A. Zinoviev in 1990, who tried to give a sense of transition, made the rounds of the world: “We are starting a new history, but we are not starting it from the beginning, but from the end. We will be at the beginning, only at the end of it». The greatest difficulty lay in the total lack of a “transition theory”, of studies and analyzes of this new and completely unstudied phenomenon.

To understand where Albania and all the former communist countries were in the years 90-91, I would like to paraphrase a statement by Michel Candesy, the head of the IMF at the time, who in a meeting with the prime ministers and ministers of these countries said: “It is a very big hole that cannot be crossed with two jumps because you have nowhere to support the foot, so a big hop must be made. We have no transition theory and no book on what to do in this period. Think of yourself as actors, authors, directors of a work called Transition.

Never in history have so many institutions, intensive and radical reform programs been engaged peacefully and with full political and social will, so many changes were implied in social relations, in forms of ownership, in employment relations, in salary and profit, in redistribution of property, etc.

Today, three decades after the start of this process, it is widely accepted that “the transition to a market economy and parliamentary democracy is the most special story of institutional, legal and social change in the context of a radical economic and political engineering operation.”

The lack of a general theory of transition, of a roadmap for major roads and reforms was the biggest problem for the political and social actors of each country, especially in a country totally isolated from the world such as Albania in the early 1990s. the / Memorie.al

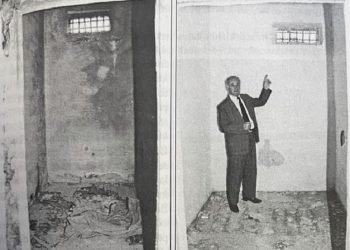

![“After the ’90s, when I was Chief of Personnel at the Berat Police Station, my colleague I.S. told me how they had once eavesdropped on me at the Malinati spring, where I had said about Enver [Hoxha]…”/ The testimony of the former political prisoner.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)