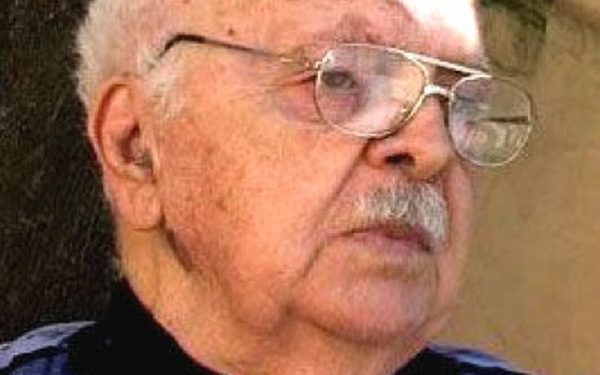

Dashnor Kaloçi

Memori.al/ publishes the unknown story of the well-known professor and ethnomusicologist, Ramadan Sokoli, suckling of one of the oldest families in the city of Shkodra, who in the 1940s graduated from the Conservatory of Florence for composition. His return to Albania and life full of vicissitudes, trying the prisons of the communist regime for years together with their two brothers and their father. The creepy ordeal of the prominent intellectual who was forced to sell the piano to pay the fine imposed by the Folklore Institute…?!

Not far from the center of the capital, near the “Barricades” street, on the ground floor, or more precisely in the basement of an old Tirana house, owned by the famous Petrela family, until a few years ago lived the only famous professor and renowned musicologist, Ramadan Sokoli. Ever since the loss of his wife, a noble woman from the Petrela family, the renowned musicologist has gloomed his days with the worry of irreversible loneliness. An ordinary visitor entering that house would scold himself for mistakenly stepping on a medieval museum, or an art gallery of antiques intertwined between old and new books, where classical and modern scores were found. everywhere across its shelves and drawers. Years ago, here a decade ago, when the famous professor was not burdened by health and memory, after several meetings in that brilliant environment of his house where he wanted to enjoy it again, with much effort we arrived “Persuade” him to write something from his life. Or to put it another way, to mark pieces from the long ordeal in which he spent for nearly 45 years under the communist regime.

The Sokoli family in the chronicles of Evla Celebi

If you dig through old books, further into the depths of the centuries, you will come across the Sokoli family in the memoirs of the Turkish chronicler, Evla Celebi, who has described it as a large land-owning family. At that time the family was known by the surname Dervishaj, where almost all its members were educated in the most famous colleges and universities of the time. According to the famous Turkish chronicler, during the reign of the Bushatllins, that family married them. Thus, the penultimate Vizier of the Bushatllins, Mustafa Pasha, married his brother, a girl from the door of the Dervishajs. From this marriage two sons were born, who were the nephews of the Dervishajs, and after the death of their father, that family was completely wiped out by the last Vizier, as a result of deep contradictions and internal family animosities. The two sons of this family who were called; Mahmut and Dervish, grew up in the Sultan’s palace in Istanbul. Mahmut had two sons; Hodon and Ibrahim, while Dervishi had a son named Duro. Abraham had a son; Isufin, while Hodo, Mahmut’s son, had a sister married to the Vizier of Bar, and another to Iljaz Pasha Dibra (Chairman of the League of Prizren). Hodo himself, who was a cousin of the famous Oso Kuka, had graduated from the Istanbul Military Academy. For some time, he had served as the district commander of this city, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. At the time of the deep eastern crisis, Hodua came back to Albania, appointed by the border surveillance commission. Jusufi (Ramadan’s father), was educated in Shkodra and Istanbul, without being able to graduate, while Ibrahimi, after graduating with honors from the University of Law in Istanbul, worked as a judge, or more precisely as an interpreter of the Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini.

Yusuf and his three sons, in the prisons of the communist regime

For the first time, Ramadan’s father, Yusuf, would be ousted from his hometown, Shkodra, by the Turks at the beginning of this century. After leaving Shkodra, he settled in Bosnia and Montenegro. In 1913, Jusufi married a girl from the well-known Jukaj family in Shkodra, whose name was Aisha. From this marriage 9 children were born to them; three sons and six daughters. During the Italian occupation (1939-1942), for his anti-fascist convictions and activity, Jusuf Sokoli was interned twice on the Apennine Peninsula. During that time, Ramadani (the second of the brothers), who in those years was studying at the Conservatory of Florence, occasionally went to see his father at the place of exile. This fate was also suffered by Aisha in the First World War, who at the time of the riots that included Shkodra, was imprisoned twice by the Austrians. After the end of the war, Jusufi was arrested again by the communist regime and imprisoned for two years in 1946-’48 in the city of Shkodra. Jusuf Sokoli’s conviction came after he was accused of participating in the Postriba anti-communist uprising. Likewise, shortly after the end of the war, Yusuf’s first son, Ibrahimi, who had graduated in law in Belgrade in the late 1930s, was arrested. Ibrahimi at that time was known among the cream of the young intellectuals of the city of Shkodra and in the period of fascist occupation he had joined the Legality Movement. Ibrahimi had a very tragic fate, as he spent almost his whole life in prisons and internments, serving a full 27 years in prison, together with his wife Shano Hasan Dostin, and this prisoner for political crimes. After Yusuf and Ibrahim, also in 1946, he was arrested and sentenced to 5 years in political prison, even Ramadani himself, being accused of agitation and propaganda and as a participant in the Postriba uprising. Ramadani served his entire sentence and was released from prison in 1950, after working in the canals and swamps of Beden in Kavaja, described as an “enemy of the people”. How to complete the Sokoli family register in 1960, he was arrested and sentenced to 25 years in political prison and his third brother (the youngest of three brothers) Hodua, who was re-sentenced to prison in the Spaç uprising. Hodua was released from prison only in 1990 (at the end of that year), with the intervention of a high-ranking figure in Albanian culture, who was a close friend of Ramadan. The parents of the Sokoli family, Yusuf and Aisha, died shortly after each other in 1957.

Ramadan by the Conservative of Florence in political prison

Ramadan high school by three brothers Sokoli, was born in the city of Shkodra in 1920. He completed primary school in that city in 1927- ‘31. From the second grade of that school he taught music notes and played several musical instruments. He finished high school at the State Gymnasium in 1931-’39 in the same city. After graduating from high school, he was sent on a study permit to attend the Florence Conservatory in Italy for flute and composition. During this time in this Conservatory, Ramadani had a great company with Qemal Stafa, Kristaq Tutulani, Qemal Draçini, for whom he kept the best memories of that past time. In this Conservatory Ramadani interrupted his studies in 1944 and after that he returned to his hometown in Shkodra where he was hit by the infamous whirlpool of the “class war” which hit the improvised dungeons of Shkodra prisons and Beden swamps in Kavaja district. In these premises, Ramadani would start for the first time the acquaintance with the cream of Albanian intelligence who would be the “professors of another university” for him. “It was in such circumstances when I was a political prisoner that I started dealing with folklore. Since some of the accomplices who were there were chosen bearers of folklore, I took the opportunity to collect valuable material from them. It was there, researching our national vision, orally inherited from generation to generation, that I became convinced that our homeland is a place chosen for folklore trackers “recalled prof. Ramadan the beginning of his future profession. After his release from prison in 1951, he settled in the city of Tirana as if to somehow escape the “claws” of the class war.

The vicissitudes after his release from prison

During his imprisonment, Ramadani was able to cultivate a large culture in the fields of folklore and musicology from many of his cell “colleagues”, which served as his “raw material” in the compilation and subsequent compilation of two textbooks. that would become his “patent” in the saponified path of ethnomusicology. After settling in Tirana, alone, without any support, he knocked on the doors of the state administration to look for a job related to music, tightly holding the two recently completed books under his armpit. From the great shortcomings that they had at that time in the textbooks and mainly those of the cadre music that were needed in this field, he manages to be employed in the Albanian Philharmonic. In this institution he works for a while because his biography was found out as “enemy of the class” and he was fired quickly. After that, after several interventions, he was able to resume work in the capital as a music director at the House of Culture from 1952 until 1954 when he was fired again. With great difficulty because he was in great need of the teaching staff of the music sector he was arranged as a teacher at the Artistic High School “Jordan Misja” in Tirana. In this Lice Ramadani worked without interruption in the midst of many vicissitudes until he retired in 1980. During all these years Ramadani was continuously engaged in studies in the field of musicology and folklore, managing to become one of the main and only personalities in this field. At the Lyceum of Arts, Ramadan has taught a variety of subjects such as flute, musical folklore, harmony, music history, solfeggio theory, chamber music, etc. On his initiative he was included in the curriculum of high schools and the subject of musical folklore for which he drafted the relevant texts which are still studied today. In this subject, he has taught at the Higher Institute of Arts for 10 years in a row, preparing relevant elaborators rich in various instruments.

His music is played all over Europe, not in Albania?!

In addition to teaching at the Lyceum of Arts and the Institute of Arts, prof. Ramadani studied and composed dozens of chamber music pieces which were performed in all the countries of the so-called People’s Democracies of Eastern Europe, and in his country, they were not allowed, due to biography. Many of the study articles that prof. Ramadani managed to publish in the specialized institutions of the country, they were taken and translated by foreign musicologists by publishing them in prestigious magazines and publications of world culture and art. From these publications prof. Ramadani managed to establish his personality and profile in this field, which would make him very well-known and sought after by his counterparts from different countries. Thus, dozens of letters have come to him from various personalities of music and folklore from many countries of the world, having a correspondence that was often checked by the competent bodies (State Security) which stopped the answers of these letters. Also, before the ’90s prof. Ramadan has been invited by many academies and well-known personalities of music and folklore, such as Tokyo, Spain, Bucharest, Prague, Oslo, Sofia, Pristina, etc. But he was never allowed to attend these activities and meetings because of his biography. Many art personalities who came to Albania would invite him to meet him and many of them would not be able to meet him after the answer “he went with the service is not in Tirana”. The few who managed to contact him, were checked by protocol, in the hotel “Dajti”. Also prof. Ramadani is one of the founders of Albanian folk festivals, or more precisely these festivals start with Ramadan. Regarding these, he recalled: “After we had done a colossal job together with colleagues in the preparation of these festivals, there were cases when I was not invited at all to attend it in Gjirokastra. When strangers came to ask about me, my colleagues shrugged and did not know how to answer them. I have not seen some of these festivals in Gjirokastra, although I was one of the main organizers in their preparation. “The right to attend folklore festivals, in Gjirokastra prof. Ramadan won him only in those of recent years, as that thing caught the eye of foreign guests asking about the reasons why he was not there. Although these vicissitudes had already become commonplace for him and did not impress him much that he had been taught, many foreign colleagues wrote to him expressing regret “why he had been ill”, and that he had not been able to follow the fruits of his work. Regarding his great work in the field of musicology, Ramadani says: “In the first place, this lacked state support. The research of ethnocultural traditions is not and can never be the monopoly of any state office or institution, but it is the right of every person who will do a little for his homeland. The Institute of Folklore (today the Institute of Folk Culture) has long had the conditions to do a fruitful job, but nevertheless, the most significant achievements in our cultural field are mainly due to volunteer initiators who have felt within themselves the moral responsibility for it. researched. “Meanwhile, the above-mentioned Institute not only did not support the trackers who worked outside its bosom, but on the contrary, it prevented them, and even fought some of them fiercely by blocking the publication of their works and plotting dangerous traps”, he recalled with pain prof. Ramadani.

Sells the piano, pays the fine of the Institute

In the mid-80s, by the Publishing House “Naim Frashëri” prof. Ramadan is asked to prepare a special book with study articles on research in the field of Albanian folklore. After several years of work, he managed to complete the study volume and submitted it to the Publishing House where three reviewers and three editors were appointed to deal with the publication of the book. After a good work by this assigned team, this book was published for publication and the first copies were published which would be checked once again by the relevant bodies to give the final approval. When the volume had crossed almost all the barriers and its distribution was expected, the order came “from above” that it should be blocked. By the Institute of Folklore, it was said where it should be that “waves have no crystallized motion, they do not have a defined structure…”. Following this remark, the Institute ordered that the remarks made by this Institute be corrected and repaired, and then that the book receive the final publication and distribution. To do this, many bottles and cartridges had to be broken where someone had to take responsibility for the scarcities and pay for them. Pasi prof. Ramadani made the adjustment and “repaired the mistakes” according to the remarks made and eagerly awaited the publication of the book, the bill came to pay 16,000 ALL from the damage caused to the Publishing House with the reprint of the book! Regarding this prof. Ramadan recalled: “This thing fell on me like a bomb. At that time, I was preoccupied with the girl’s wedding and that a lot of money hurt me a lot. So, I was forced to sell my piano to wash away the fine imposed, as I had no other choice as I had also shared the wedding day. “When I took the piano out of the house, I was in the same condition as when I took out my parents’ coffins from there.”

Published books and two documentaries

Although prof. Ramadan had several books ready for publication for years, for the first time their publication began in 1958. From this year until 1995 when his last book “16 Centuries” was published, 13 books were published only inside country. Several other books have also been translated and published in several European countries. The writer Ismail Kadare, in the magazine “La Letrus Albanese” has published over 200 pages only for the creativity of prof. Ramadan Sokolit. Some of the titles of the works of prof. Ramadan Sokolit have been included in foreign encyclopedias as well as in UNESCO bibliographic catalogs. These were greeted and appreciated by the German musicologists Doris Stockman, W. Fiedler and E. Stockman in the “Albaniesen Volkmusik” Berlin 1965. Also the English musicologist one of the most famous in the world A.L.Lloyd in some issues of the magazine “Int. Folk Music Council ”has reviewed some of the works of prof. Sokol. His works have had a great echo, especially in the Arbëresh of Italy and in Kosovo, where the well-known musicologist, Dr. Rexhep Murushi, has dealt a lot with Sokol entomusicology. In addition to these works prof. Sokoli in 1957 led the first ethnomusicological expedition in southern Albania in collaboration with a team from the East Berlin Academy of Sciences, and in 1969 led a second expedition in northeastern Albania, in collaboration with a team from the Romanian Academy of Sciences. Some of these works of prof. Sokolit, of popular music and folklore, have unfortunately been wiped out of the reels and others have been appropriated by some plagiarists who have vegetated in this Institute. In addition to these works prof. Sokoli has made several documentaries with Kinostudio “Shqipëria e Re” such as those about Jan Kukuzeli, Niket Dardani, Lorenc Tardo from Arbëresh and the musician Gjon Kujxhia. For the realization of the first two documentaries prof. Ramadan has had many vicissitudes from the Central Committee, being accused of having brought to those Vatican religious choirs. After many very serious problems that are presented to you in relation to these, it took the intervention of Ramiz Alia to allow their transmission.

Avoided and forgotten even after the ’90s

Although with a colossal work and between many vicissitudes during the period of the communist regime, where he was not even given a badge by the teacher, prof. Ramadan Sokoli unfortunately even after the ’90s said that he continued to feel himself as such?! Most of his musical creativity lay in his drawers without being able to see the lights of the stage, although there is a very high-quality work based on the evaluations of foreign colleagues, the result of several years of study work. He was only awarded the title of Professor in 1995, and in those years, he was able to go abroad for the first time teaching at the Universities of Rome, Istanbul, Rudostald, Germany, Bratislava, Athens, Bologna, Ravenna, Italy, etc. Numerous invitations and letters often came to his address informing him of various lectures, such as in recent years one of the gatherings of the Albanian diaspora in Arbona, Switzerland, where he did not have the opportunity to go, he sent his statement which was read there. Also due to the lack of support from state bodies, prof. Ramadan could not even go to the US where he was invited by the University of Michigan, for a cycle of conversations about the Albanian ethnocultural tradition. During the years 1990-1995, prof. Ramadani was a member of the Steering Council of the Albanian RTV and in the same year he directed the nationwide Folklore Festival of Berat. Meanwhile, he has been elected by the Albanians of Macedonia for five years in a row as the chairman of the jury at the folklore festivals of Tetovo and Struga. In recent years, although at a broken age and very tired from the vicissitudes of a life full of endless suffering and stress, prof. Sokoli continued to work on his creativity. So, a few years ago he went to Italy (at his own expense) and brought to Albania one of the photocopies of one of the earliest monuments of Albanian musicology, the Antiphonarium compiled in the 15th century by Gjergj Danush Lapcaja from Durrës in Monopoli. Likewise, shortly before he passed away, he was in charge of revising five monographs in musicology and folklore. Although the fame of prof. Ramadan Sokolit is already known by many foreigners who highly appreciate his work, this did not happen in Albania, where he felt and was completely excluded and without any support from the state authorities of art and culture?! Likewise, prof. Sokoli was not even elected as a member of the Academy of Sciences in the choices made by this Academy shortly before he passed away. In this regard, prof. Ramadani said: “This reminds me of a great French writer who was officially ignored by his country. Before he died, he instructed his relatives to write an epitaph on his grave saying: ‘He was nothing, not even an Academician”/Memorie.al