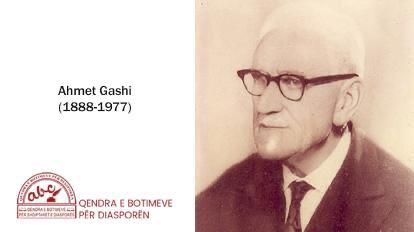

Gani Demiri (Ratkoceri)

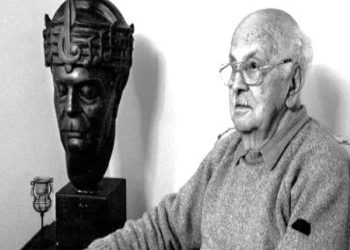

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known pedagogue, researcher and historian, Gani Demiri (Ratkoceri), originally from the village of Llugaxhi in the municipality of Lipjan in Kosovo, a former political prisoner who suffered for years in the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, who a few years ago published in Tirana a monograph on the famous professor Ahmet Gashi. How Gani Ratkoceri describes Professor Gashi in his memoirs, from the origin of the family, his education in Prishtina, Skopje and Istanbul, his patriotic commitment for the benefit of the Albanian cause, to his contribution and colossal work for the spread of education in Albania from 1913 when he ran the Normal School of Elbasan, until he passed away on September 1, 1977.

I met Professor Ahmet Gashi for the first time in 1941-’43, when he came to my village, Llugaxhi, in the municipality of Lipjan in Kosovo. But at that time, I did not fully understand the whole all-round and majestic personality of this extraordinary man. I achieved this only in 1956. Since then I have felt very indebted to this giant and volcano for the national cause, so I thought and dreamed to illuminate his life even with a modest monograph, like the one I am presenting to the esteemed reader… I remember how the eminent professor exploded with full enthusiasm whenever it came to the Albanian enslaved lands, Kosovo and Chameria, for which he did his best to sensitize the Albanian public orally, in writing, with textbooks and geographical maps, and these the latter had continued until the age of 80-87 years. A rare case in our education: 54 years with a diary in hand, with maps of geography, history and ethnography, with books and magazines of the time until he passed away, on September 1977. This book would honor every Albanian library inside and outside the motherland, ie in Kosovo, Macedonia, the Presevo Valley, and Montenegro, because it sets a great example for a noble and patriotic man.

Brave and indomitable fighter for the national cause

Here, briefly, are the highlights of his life.

- In the general Albanian uprising of 1912, when the Ottoman Empire had deployed 70,000 soldiers in Kosovo under the command of Fadil Pasha, the young Ahmeti sided with 60,000 Albanian fighters led by Hasan Prishtina. As a high school professor and secretary of the patriotic club there, Ahmeti did his best to liberate Prishtina by shedding as little blood as possible. It was also to his credit that the Turkish army could not get out of the barracks, and the Albanian fighters entered the victorious city, cheered by the people of Pristina. This event caused a stir in Europe at that time.

- From the years 1913-1933 prof. Ahmet Gashi taught and directed the Elbasan Normal, where the people were also divided between the party of “bey” (Shefqet Vërlacit) and the party of “pasha” (Aqif Pasha), and still fanaticism had strong roots in mentality and culture. In these conditions, prof. Gashi founded the cultural society “Aferdita” (1918), the string orchestra with the violin, challenging the opinion of the time that identified the violinists with the “gypsy party”, established the club of intellectuals and theatrical group, and developed the football sports organization. Everything in function of the national cause and cultural education.

- From 1933 she taught at the Women’s Institute “Nana Mbretëreshë” in Tirana where she helped a lot in the design and publication of textbooks and school dispensations, so necessary to increase the efficiency and quality of the lesson. He always worked for the spelling and orthography of the Albanian language, not only in the class he led, but also for their colleagues and their textbooks. In this regard, he followed the message of the “Albanian Homer”, Father Gjergj Fishta, who wrote: “Cursed be he who speaks in a foreign language, when there is no need.” Also, of the great Naim who wrote: “Albanian language, how beautiful, how good, how sweet, how pure”. While the well-known poet Dom Ndre Mjeda had said: “One of these languages that I feel for you, are beautiful with a foundation, but still this is like a shadowless sun, for me the outside world succeeds”. This assistance of Professor Gashi has been very well noted by the honored professors Xhuvani and Çabej.

- When he was the director of the Gymnasium “Sami Frashëri” of Prishtina in the spring of 1944, prof. Gashi managed to escape from the clutches of the German Gestapo there, 87 young schoolchildren participating in the network of communist groups and activities and discovered by Italian SIM agents. In this study we have included important articles written by or about the professor, as well as many memories collected by his former student and colleagues across our homeland, although there may be some repetition here and there, for which we apologize.

The relocation of the Gashi family from Kosovo to Elbasan

It is really a great pleasure to write about Professor Ahmet Gashi, but at the same time hard work. This is because, on the one hand, Ahmet Gashi is perhaps the last renaissance of Albania and a man I have known personally, on the other hand, he has such a rich, wide and multifaceted life and activity. Prof. Ahmet Gashi was born on September 1, 1888 in Prishtina (Kosovo). He comes from a poor family of thousands of those forcibly displaced from ethnic lands in the former Sandzak of Nis, right after the humiliating Treaty of St. Stephen, this treaty for the tragic Albanians, which followed the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-’78. At that time, about 300,000 Albanians from those districts left their lands and property and headed for Kosovo and Turkey. Those who settled in different parts of Kosovo, suffered as well as their fateful compatriots in Turkey, due to disinterest and contempt by the then Ottoman state. Professor Gashi himself describes the situation of his family as follows: “My father was called Ibrahim Latif Gashi from the village of Pllavcë near Leskovac, my mother was called Metije Ismail Thaçi, from the village of Zhinipotok, near Leskovac. In 1878, forced by the barbarism of the Serbs who burned and devastated those provinces, they moved as Muhajirs to the districts of Pristina. Here I was born on September 1, 1888, on March 6, 1914 they were able to come to Elbasan. In this city my father died in 1915, and my mother in 1930. My father was a tanner at a merchant in Prishtina. The mother was a housewife but also worked at home with fabric looms for clothing, for a small fee from the owners of the manufactories. “I still have the groans of both of them in my ears, because of the hard work they did and the misery of our family.” Ahmeti grew up in these conditions but was educated with love for his nation and homeland occupied by the Ottomans and torn apart by barbaric neighbors. His parents had a great desire for him to get a good education, especially his mother, who did a lot to get him educated. In his memoirs, regarding this aspect, the professor writes: “More than my father, I had a good educator mother. With her sweet advice she aroused my love for knowledge and encouraged me to go to school and study there diligently. “Sacrificing from the family economy, she provided me with school clothes and books and everything I needed as a student.”

Students in the primary school and gymnasium of Prishtina

So great was the joy that little Ahmeti felt when his mother bought him school books, that that night he slept with them under the pillow, seeing beautiful dreams for the class, the bench where he would sit with two or three other people, even in the first place to see the teacher better and hear every word he said. That morning, when he was going to school, Ahmeti got up early, while his mother had prepared everything he needed, and she even accompanied him to school herself. Love for mother, school and natural inclinations made young Ahmeti successful in lessons in both the first grade of school in Prishtina. This also helped him pass the competition required to pursue a high school diploma. Ahmeti himself tells about this: “How I finished primary school and lower five-year gymnasium in Pristina, I was tested with a competition and won the scholarship of the Albanian club” Youth of the Fatherland “, to continue the high school classes in Skopje, then the capital of Vilayet of Kosovo.

Learning and patriotic activity in Skopje

The transition from the warm bosom of the family to the dormitory mixed with completely unknown students was overcome very quickly and easily by the boy Ahmeti. Given his unwavering desire to become worthy of himself, his family and his homeland, Skopje seemed more changeable than similar to his hometown of Pristina. It was similar in many mosques, but distinct for the beautiful Vardar River that flowed through it, to the majestic Dardanian fortress, where Turkish soldiers were stationed, to neighborhoods with crowded houses and not to special neighborhoods like in Prishtina, with houses covered with straw and without windows, with some pieces of glass glued to the mud, where lived all the displaced from the areas occupied by Serbia and used by the rich of Prishtina. Undoubtedly the most important difference was that in Skopje the majority of the population spoke Albanian, in the city and in the districts, while in Prishtina Albanian was spoken only in the neighborhood with caps, “the neighborhood of the Muhajirs”, as it is still called today. Students from Rumelia lived in the dormitory: Macedonians, Greeks, Bulgarians, Vlachs, from national minorities, whose contemporaries already had independent states from Turkey. The Albanians who made up 4/5 of Rumelia meanwhile were still under the Ottoman yoke. Non-Albanians were able to read freely in their mother tongue, newspapers, magazines, books, brought to them by the relevant national government, or printed without hindrance even in Rumelia itself, while Albanian students still had this privilege. Here is what the professor writes about this: “In the gymnasium in Skopje I had friends of Serbian, Bulgarian, Greek nationality, etc. They told me that newspapers, magazines, books were coming to them in their mother tongue. Reading these materials, I learned what was written about Albanians, who presented themselves as Turks, and that supposedly we Albanians were their occupiers. This irritated us and we wondered why this discrimination against us Albanians, why they have national rights and we do not? That’s how I thought we Albanians would create a club. I talked to friends and we decided to set up our club. In fact, the national feeling was awakened and developed in me as a child, because the events of the Albanian League of Prizren were not only not extinguished, but were reinforced in the men’s rooms and I listened to the stories about them with great pleasure from the mouth of the former active participants. I heard about the Frashëri brothers, the Istanbul Committee, Vaso Pasha, Hoxha Tahsini, Zija Prishtina, etc. The club we set up also started to spread the illegal Albanian press, not only in Skopje but also in other cities. There were books, newspapers and magazines that were published at that time in Romania, Bulgaria, America and elsewhere. All this strengthened my love for a free Albania …” Regarding the lessons, Ahmeti writes: “I always went to every class of the gymnasium, I helped my friends, because even by my nature I was inclined to teach them others patiently. “But in this way, I also strengthened my knowledge.”

Student in Istanbul

The young Ahmeti, after finishing his studies at the Skopje Gymnasium, won the right to high school in Istanbul, again through a competition, while also securing a scholarship, which was necessary, especially for him, who came from a poor family. He started his life as a student at the four-year Higher Pedagogical Institute. While in high school, he read extracurricular literature and learned foreign languages, in addition to Turkish and Oriental languages, as well as French. In the latter he had read about classical Greco-Roman history, medieval literature and history, as well as the Renaissance. So, he went to Istanbul with a satisfying cultural background. And it was not difficult for him to adapt to the new conditions there. Of course, life in the Ottoman imperial metropolis was significantly noisier and livelier than in the provincial capital, Skopje. Ahmeti was aware, however, that this metropolis now represented a declining empire, seriously ill, and making no serious effort to heal and reform. With each passing day she lost a piece of her large body. Within this collapsing building was Albania with its four vilayets, Kosovo, Bitola, Ioannina and Shkodra, with an area of about 92,000 square kilometers. The Albanians had to fight to get out of this building as soon as possible before it took over the building, turning it into a ruin. The future professor found this lesson in the local patriots, Ismail Qemali, Hasan Prishtina, Nexhip Draga, etc. In his memoirs, he writes: “In Istanbul I met many Albanian patriots, such as: Ismail Qemali, Hasan Prishtina, Nexhip Draga, etc., who advised and instructed me on how to work for our common national cause together with my friends. mine. I also met with fellow Albanian students from different faculties, such as Ali Mihali, Zejnelabedin Voci, of the Faculty of Medicine, Ragip Lekë. Neki Delvina from the Faculty of Law and many others. Especially many Albanian students came from the vilayet of Ioannina. We distributed national literature to newly arrived students in Istanbul, thus helping to awaken and strengthen their national feeling. I continued this work even after I was appointed a teacher in the gymnasium of Prishtina, with the students of the city and the village. This time, the propaganda materials were brought to me by our students who were returning from Istanbul for a vacation “.

Activity for the Albanian alphabet

Seeing that the Albanians opened Albanian schools in their four vilayets with the Latin alphabet, the Young Turks started the propaganda through their Albanian servants, against this “kaurr alphabet”, and proposed the “easier” Arabic alphabet. Two Albanian-speaking Albanian MPs, Fuat Pasha from Pristina and Seit Hoxha from Skopje, drafted an Albanian-language primer in Arabic letters and began experimenting with it in schools. This infuriated the Albanians immensely, especially in Kosovo and in the Pristina Club, which had become the main propaganda center for the national cause, Albanian education, etc. The leaders of the club, Nazmi Gafurri and Ahmet Gashi, immediately held a meeting of the club with the supporters and shared the tasks for unmasking this anti-national project. At that time great fanaticism and ignorance, it was really hard and bold to come out against the Arabic alphabet. Until then, the common people, the imams used to say: the sun does not shine without the Sultan who is the caliph (the first of the religion). At that time in Prishtina, as a city with more soldiers than inhabitants, it had 20 mosques. Thus, the two deputies in question found it easy to work with the primer in Arabic letters, because they also enjoyed the support of the government of imams. Of course, the main work fell to prof. Ahmet Gashi, as he was both the most prepared and the most communicative with the common people, as well as with those of the upper class and the ulema (imams). Professor Gashi had to do an extraordinary job, day and night, to refute the Arabic alphabet. First he talked to the city authorities one by one trying to convince him how the Albanian language could not be written in Arabic letters, but only with the letters of the Istanbul alphabet, drafted since the time of the Albanian League of Prizren on 1878, in which many books have been written and published up to that time. He even showed them these books and recited excerpts from Vaso Pasha’s poems, because how I saw them was believed more by them. Moreover, Vaso Pasha was a Catholic who had become a pasha and had written so beautifully in Albanian with the letters of the Istanbul alphabet, which was later improved from the Monastery Alphabet in 1908. After the pariah was convinced and promised to write the memorandum (memorandum) that they did not accept Albanian primers with Arabic letters, but only with those letters of the Istanbul alphabet, the professor talked to the main imams who gave him the word as the pariah of the city. A meeting was then held in the club hall, where after lengthy discussions, it was decided to send a memorandum to the Young Turk government, the Sultan, MPs Hasan Prishtina and Ismail Qemali, by which the four-letter primer with the Arabic alphabet was opposed and accepted only that with the Istanbul alphabet. And so, it was. /Memorie.al