Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al / The unknown and painful story of the Catholic clergyman who graduated in Austria and worked for 20 years in collecting folklore in Northern Albania. The testimony of his nephew, Luigj Palok Gjergji, regarding the arrest of Father Bernardin Palaj only one day after he had returned from the meeting with Enver Hoxha in Tirana and how they found his body lying on the ground and drowned in blood at the Franciscan Assembly that was returned to the State Security prison cell…

Just a day after Father Bernardini had returned from Tirana where he and several other Catholic clergymen had been summoned to a meeting by Enver Hoxha, he was arrested and locked in one of the rooms of the Franciscan Assembly which the Security had turned into a prison. During the time he was being held there, he was tortured in the cruelness way and none of our family could meet him. On December 2, 1946, we were informed to go to the Assembly to see her, and there we went: me with my mother, Lisa, and my grandmother, Nusha. We were not allowed to enter the courtyard of the Assembly, but the outer door was slightly opened and from there we saw Bernardin’s body lying on the ground with the veladon all blood attached to the body. Security people told us that he had died of natural causes and gave us some of his personal belongings and belongings quite trivial. “We asked to take his body with us to bury him, but they did not give it to us and after a few minutes they expelled us from that place as well.”

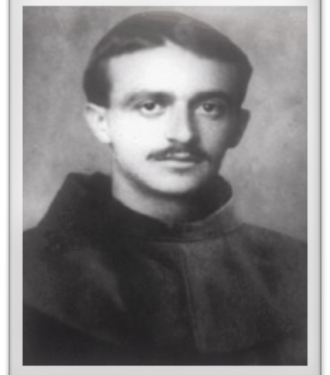

The man who speaks and testifies is Luigj Palok Gjergji, who tells the whole tragic story of his uncle, Father Bernardin Palajt, the Catholic clergyman known as one of the trackers of the largest collector of the Epic of the Kreshniks of Northern Albania. But who was Bernardin Palaj, what is the origin of his family and where was he educated? What was the research and scientific activity of Father Bernardin and how long did he work in the collection of the Epic of the Northern Kreshniks and the folklore of those areas that were known and qualified as the Visaret of the Nation? Why was Father Bernardin arrested and what were the circumstances of his tragic death in the Shkodra Security cells?

The Palaj family where Bernardini was born

Bernardini was born on October 22, 1894 in the village of Shllak in Dukagjini, where his family originally came from. His father, John Palaj, was a well-known tailor throughout the area and was known as one of the most devout believers in the Catholic religion. While his mother, Maka, was a housewife who spent her days dealing with housework and weaving in the avalanche. Bernardini was the first of the children and was followed by two brothers and a sister. Regarding his and his family’s past, his nephew, Luigj Gjergji, testifies: “Bernardin’s older brother left Albania around 1925 and emigrated to the USA, where he married a girl of Australian origin. Until the end of his life he lived in Brooklyn, where he owned a hotel called “Juvenilja” and a large pharmacy where his wife worked. While Bernardin’s younger brother, Gjon Palaj, took over his father’s craft, becoming a famous tailor. Gjoni spent most of his life until 1948, when he passed away, working in Tirana, working as a tailor for the famous Gjon Laca, who had his workshop in the Kacelëve house. While Bernardin’s sister, Nusha, has lived constantly in the city of Shkodra and is known as a folk doctor. Nusha died in 1953 and she left two sons and three daughters, one of whom, Liza Gjergji, is my mother “, Luigji testifies about the family of Father Bernardin Palaj, whom his mother, Liza Gjergji, had as an uncle.

From Austria to Dukagjini

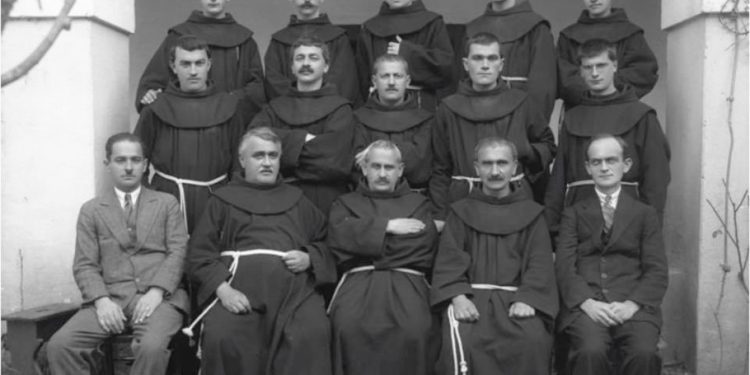

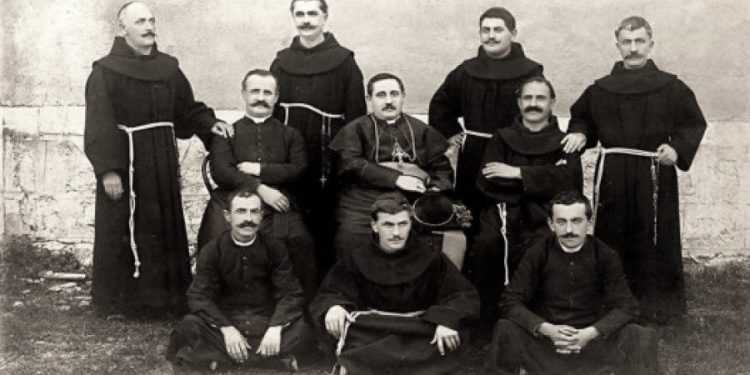

Bernardini received his first lessons in elementary and unique school at the Franciscan College in the city of Shkodra, where after graduating with excellent results, he was sent to further his studies at the Theological High School in Salzburg, Austria. After graduating from the Lyceum with very good results, he further pursued higher studies at the Faculty of Theology in the city of Innsbruck. Regarding this and Bernardin’s later ecclesiastical career, Luigj Gjergji testifies: “After receiving his diploma, Bernardini returned to Albania and in 1911 he surrendered as a friar to the Franciscan Assembly in the city of Shkodra. After staying with that Assembly for several years, in 1918, Bernardin was granted the priesthood by surrendering as a priest, after which he went to serve in some of the parishes of the more remote villages of the Upper Shkodra Highlands.

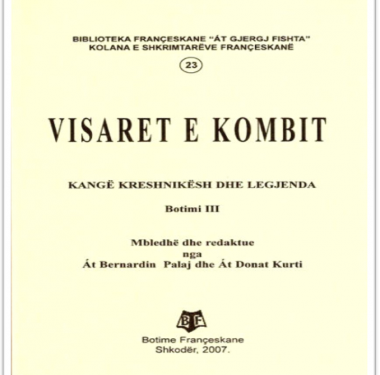

Around 1920, Bernardini was appointed professor of Albanian language and Latin at the Gymnasium “Illyricum” in the city of Shkodra and in that college he worked closely with its director, Padre Gjergj Fishta, who promoted him in the field of studies on customary customs and folklore of Northern Albania. Father Bernardini continued that research and research work during all those years that he served as a professor at the “Illyricum” gymnasium, collaborating closely with his friend, Father Donat Kurti, with whom he occasionally undertook research expeditions in the villages of deep of the Northern territories. In those remote areas he also cooperated closely with about 40 parishioners, who were given the task of gathering the Epic of the Northern Kreshniks and the various docks and customs of those villages where they served. In addition to the ongoing field research that lasted for nearly 20 years, Father Bernardini also studied the Epic of the Knights Templar, and in 1940 he began publishing them. At that time, he together with his closest friend and collaborator, Father Donat Kurti, published in four volumes, the book “Songs of saints and legends”, which had a great echo and was highly praised by the personalities of her letters. time, such as Xhuvani, Çabej, Dosti, Padër Anton Harapi etc., who called that volume: “Albanian Iliad”. After that in 1942 Father Bernardini started publishing his studies in the magazine “Hylli i Dritës” with the study: “Doke e kanun në Dukagjin”, which continued in several issues in a row, which was also published in Rome in 1944 “A large part of Father Bernardin’s studies were published in 1943 in various textbooks,” recalls his nephew Luigj Gjergji, regarding the study work of his uncle, Father Bernardin Palajt.

Tragic death in Security cells

After 1944, Father Bernardini lived both in Shkodra and in Tirana, where he often came to publish his scientific works at the Institute of Albanian Studies with which he had collaborated since the war. His scientific works were highly appreciated even after the end of the War, where one of the most famous scholars of the Albanian Epic, the Russian Denisckaja, in one of her studies expressed superlatives about him, saying: “Father Palaj is the deepest connoisseur of the mountains our “. But the long research work that Father Bernardin Palaj had begun in the early 1920s could not continue, because like most Catholic clergy he was ousted by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha. In this regard, his nephew, Luigj Gjergji, testifies: “On October 22, 1946, just one day after Father Bernardini had returned from Tirana where together with some other Catholic clergy were called to a meeting by Enver Hoxha, he was arrested and locked up in one of the chambers of the Franciscan Assembly which the Security had turned into a prison. During the time he was being held there, he was tortured in the cruelness way and none of our family could meet him. On December 2, 1946, we were informed to go to the Assembly to see her, and there we went: me with my mother, Lisa, and my grandmother, Nusha. We were not allowed to enter the courtyard of the Assembly, but the outer door was slightly opened and from there we saw Bernardin’s body lying on the ground with the whole blood veladon attached to the body. Security people told us that he had died of natural causes and gave us some of his personal belongings and utterly insignificant items. But the truth was quite different, because his death had come from the torture and tetanus disease that had been slandered to him in those days by the barbed wire that had bound his hands. We asked to take his body with us to bury him, but they did not give it to us and after a few minutes they drove us away. From that day on we could not learn any clue as to where his body was buried, but five years later word spread that Father Bernardin, along with six other clergymen who had been tortured to death, had been buried in the pit. of lime there at one end of the Franciscan Assembly. In addition to this news, we were told that the body of Father Palaj was buried in a place with the body of Dom Lazër Shantoja, inside the perimeter wall of the Assembly. But all these were just words from kind people, because in fact our family could not find the remains of Father Bernardin even today “, concludes his story Luigj Gjergji, regarding his uncle, Father Bernardin Palaj, one of the greatest scholars of the Northern Kreshnik Epic, who died in Security tortures in December 1946, when the communist government of Enver Hoxha was promoting free and democratic elections.

Ernest Koliqi: Father Bernardini was the “brother of kangvet”

For three days I felt in Palç without my brother, you waited for him. The mercenary and the salaried woman looked me in the eye to investigate and quickly to fulfill my smallest wish. I did not miss the prison in those peaceful cells. However, to be honest, those three days without my boyfriend and girlfriend seemed long to me. Not that I hate loneliness. On the contrary, I often love and seek it as an enviable thing. To me, qi she is always fertile. But the loneliness of the mountains had begun to overwhelm me; the loneliness of a citizen among the Mountaineers, with whom we can never open, because of the radically different mentality, a spiritually exhausting relationship. I look forward to the old friend, in the solitude of Palç’s cell. The loneliness of the mountains is very severe. Only those who tried it can talk about it. We who have lived outside, notice the loneliness of the big cities. You are the only Cretan there in the midst of a multitude of foreigners. Walking head to head with them, the unknown among the unknown, but there, among the ending paths full of light and movement and noise and rumble, the heart will not be crushed by a sudden desolation of desolation as in Malsi, where your language is spoken.

Even though they do not talk to you, passers-by on the outer roads associate you with smiling faces, with cheerful sympathy of glances. It feels like a regulated world, which found the finest means to fight boredom, to alleviate the terrible feeling of human loneliness, of tragic loneliness, of the soul that the body gave, captive. Blind, from other people and from all things: lonely, hence, often lonely among foreign cities. On the contrary, that of the mountains is heavy for us citizens and sometimes overwhelming.

The horror, the mortal boredom of loneliness suddenly caught me badly one night in Shosh, after two weeks I was living happily there without ever meeting people in the city. I rejoiced as usual in the evenings — until the colors of the dawn dawned, and the first deity in the cup of heaven gleamed, and you heard the music of the pure speech of the Mountaineers. As it got dark, I climbed into my room at the top of Nik Gjergji’s tower. And, there, it seemed to me very dim, sad, the small light of the chandelier with oil brought with other clothes from Shkodra. Will men of the house, cross-legged around me, talking. That evening I was not attracted to their conversation, as if they spoke a foreign language that I did not understand. As soon as they remembered that I wanted to be alone, they went downstairs with a lot of people. Nika, who was desperately trying to get rid of my boredom with a shot and gas, sent him out with angry words.

The emptiness of the room, the blackness of the ceiling trains, the beauty of the furniture, the darkness as soon as they were destroyed by the trembling flame of the candle entered my soul. I wanted Shkodra, my civic home, a citizen friend of anyone, to break that lonely clasp. And after I did not have these consolations, I felt myself miserable, terribly miserable. But it passed me by. We probably informed Nika about my sadness, the old man of the house, Prel Gjoni, climbed to the top of the tower with his zamare in his hand. He greeted me briefly and, without saying another word, as soon as he took his place away from the light at one end of the room, he began to fall into the zamares with six holes. I like his assurance that with those simple sounds he could cure any boredom of the soul. I was leaning on the psote with my head on the pillow. I closed my eyes and let out a series of sounds that were sometimes thin and high, sometimes thick and low, they were taken back nicely and you were intertwined and melted into each other. Zamarija renewed the crafts of the forest, of the fountains of mountain echoes.

When I opened my eyes, I saw the old man’s horn, a little more in the light, I felt the ground, Currlina, the young rancher. He was silent and looked at me with raised eyebrows. Later, you got up slowly and noticed me with a somewhat funny tutu, Nika came back too. One by one the men of the house lay around me again and smoked tobacco and brandy together as among other evenings. Those brief moments of sadness between the mountains make me think of the loneliness of the churchmen, of the teachers, of the clerks on the other side who live in the most lost parts of the homeland. Especially the long winter boredom, when the snow for six months awaits any relationship with cities, I say it will be terrible. But perhaps most are taught. Those who cannot be taught in the desert suffer, but the high awareness of duty, of the mission they perform in those solitary places, certainly relieves their suffering.

I weep for my brother. His parish is one of the most remote and difficult. With vivid curiosity I expect to see him there in the midst of that wild world, among the mountain people, whom I once knew the valuable and open-minded conversations between the most educated districts of the city. The friar also came, On the edge of the evening, we heard his cry from the top of the meadows. My heart was filled with joy at the roar of the horse’s hooves, which descended quickly and swiftly towards the hut.

Father Bernardin Palaj, parish priest of Mërtun with a party in Palç. That evening he came to enjoy talking about our folklore. And, the next day, my brother took me to a small room and there, on the ledges of an old shelf, he showed me all the piles of yellowed paper and thick notebooks. Kang. A thousand songs of heroes and heroines, a thousand dances of darsmash, centuries-old poetry of the Albanian people always fill it, passing from the mouths of generations in the end to that of the generations in the east. We flipped through those letters and dusty notebooks from where the spirit of an eternal spring came from. The heroic cycle of Muji and Halil was sung by Dukagjini’s rhapsodists in clear and sharp language. The same songs, but among the most colorful, most mobile variants of the great Malsis, where the singers have the most vivid fantasy. The dances of Kosovo and Dibra are full of love. Those of Shestan and Ulcinj with sea faces, thin and smooth. Those of Biza, in Cape Rodon near Durrës, are delicacies full of analogies with Tuscan forms.

I do not know who said that everywhere in the world poets sing for the people, only in the Balkans do people sing for poets. So far, for me, the greatest Albanian poet is our people. This truth, shone before the eyes of the mind in Palç, in the cell of the Kangve Brother. He, in the long solitude of the mountain, has listened to the inexhaustible kanga that springs rain from the deepest heart of the arbnuer nation and has snatched it from oblivion. The seeds of the spring springs of the new Albanian poetry sleep on the dusty leaves of Palç’s cell./Memorie.al