Dashnor Kaloçi

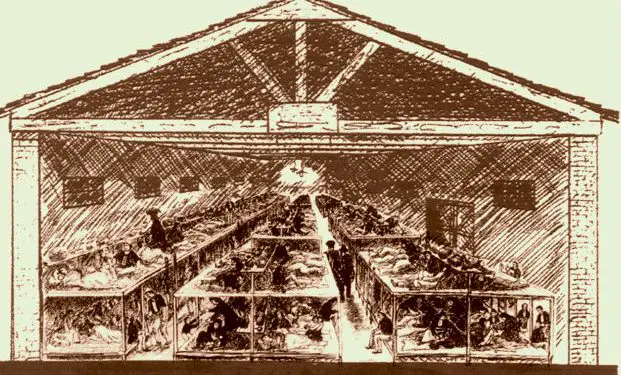

Memorie.al/ publishes some of the unknown stories that took place in Tepelena Camp, where after 1947, the communist regime of Enver Hoxha interned dozens of families who were considered by him as: “reactionaries and enemies of the people”, such as the family: Kupi , Dosti, Petrela, Frashëri, Çelo, Kola, Kaloshi, Gjonmarkaj, Previzi, Radi, Mëlyshi, Dine, Ndreu, Merlika, Dema, Gjeka, Deçka, etc., where most of them had people fled outside Albania, or fleeing through the mountains, resisting the ruling communist regime. The painful testimony of the Albanian-American Gjok Deçkaj, originally from the village of Kushe i Hotit, Malësia e Madhe and living in the USA since 1966, when he fled Albania, regarding the horrors he experienced himself in that camp , as well as those told by his mother and other accomplices who suffered there as a family.

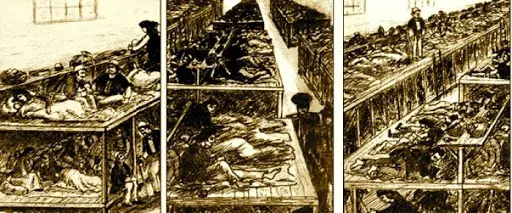

“One night, a young woman from Tropoja who was waiting to be released, went at night to open the grave of her child who had died at the age of 5, since that family had come there to Camp Tepelena. Opening the grave with the spoon we ate the soup, she cleaned the bones with her dress and said: ‘Mother will not leave you here, no’. The desolate woman was forced to break her son’s bones in order to hide them in her body clothes, without being noticed by the camp guards, as she was not allowed to take them. That night, my mother was with him, helping him, and then she was able to take her son’s bones and bury them in Theth. ”

The above testimony, which seems to be part of a horror movie script, is neither more nor less, but a very real event that happened half a century ago, in the terrible camps of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha. Gjokë Pjetër Deçkaj tells this story, who had the tragic fate of trying these camps, in which he came to life. For these and other events from his life, he tells in this interview, exclusive to Memorie.al.

Mr. Gjok, what is the origin of your family?

The origin of our family is from the village of Kushe i Hotit, in Malësia e Madhe. We were not a very big family, but my father, Mark Pjeter Deçkaj, was very well known as a wise man with a big name in that whole province. Both during Zog’s time and during the War period, the father was not involved in politics, but was known as a nationalist and patriot.

What happened to your family when the communists came to power in 1944?

When the communists came to power, we were not well received, and my father, Mark, was seen as a suspicious man. This is due to the fact that in 1945, he was forcibly mobilized by a Special Unit of partisan forces, and during that time, seeing the many crimes committed by that unit, with arrests, murders, torture, burning houses, etc., there was a hatred great for them. Shortly after he was released from that ward, in 1948, my father and grandfather, Pjetër Deçkaj, fled Albania.

How did their escape happen?

That year, in 1948, 30 people escaped from Hoti, in one day all together and crossed into Yugoslavia. This happened after a border post officer went door to door and informed all these people that they were on the list to be arrested. And that was true, as an hour after the escape, communist forces went from house to house, seeking to shoot them. Of these 30 men, the best known were; Touches Gjeto Marku, Nikoll Luc Doka, Mark Doshi Frangaj, Pjetër Gjon Luka etc. Along with these 30 people, the commander of the border post also escaped.

What happened to your family after Dad and Grandpa escaped?

I was born on September 17, 1948, at 5 in the morning (two weeks after the escape of my father and grandfather) and at 9 o’clock, when my mother (File Pashk Ademi) was still with the birth discomfort, they came and took us by force, taking us in Koplik prison. My grandmother went to Kol Maçi, who intervened with the communists and took us back to the village.

You were harassed after that?

They left us in the village for more than 3 months and on April 23, 1949, we were interned in Tepelena. The day they took us to Tepelena, my father had come near the village with two of his brave friends to take us with him to Yugoslavia. He approached no further than 500 meters from us, hearing me crying incessantly, but he could not help us. The two companions said, “Medet, Mark, what shall we do?” And the father replied: “I have never seen myself closer. “I am afraid that my son will be killed, so we cannot intervene.” After a long road trip, we were taken to the Tepelena camp. The cradle where I was, was falling off the horse’s back and held it, Bora e Prek Gjeto Markut, otherwise I would have fallen into the abyss. In Tepelena we found other families from Hoti and Kastrati and among them 13 exiled Catholic priests. I was small at the time, but my mother then told me about the unimaginable suffering and horrors we went through there.

Like what…?!

When I was growing up, my mother told me that the Chairman of the Cooperative of the villages around the camp and the party secretary had ordered the villagers of these villages in Tepelena to curse their children and throw stones at the internees. And there were some cases when when they returned from the mountain, the villagers came forward and insulted and shot the internees.

What do you personally remember from that camp, or from what your mother told you?

People died there every day from hunger and disease, mostly young children. The work was quite heavy and exhausting. The internees were working to transport timber across the Vjosa River, and when the river was very swollen, the timber hit them and left them dead on the spot. From Gjirokastra, they brought and threw them there on purpose, dead dogs and the whole camp stank.

What about the camp staff, ie police officers and non-commissioned officers, what did they tell them how they behaved and treated them?

A real horror of the Tepelena camp was a captor named Tomi, who chased young girls and brides, forcibly putting them in a warehouse to rape them.

Captain Tom, do you personally remember, or did they tell you?

I remember Captain Tom himself, because when I was 5 years old, he kept me in cold water for a few minutes, in order to put pressure on my mother. Captain Tommy committed so many atrocities against the exiled women and girls that the command itself was forced to remove him. My mother tied me to the crib belt on the bed so that I would not have a daughter, as we slept in bunk beds. From time to time, the mother was taken out in front of the whole camp and insulted by her father, Mark, saying that he was a criminal and all sorts of other insults. But his mother replied, “I know him as a very good man.” They did the same to Bora e Prek Gjeto Markut (Lulaj), but like her mother, she did not say any bad words about her husband, on the contrary, she praised him. If we had not had the help of my uncles and grandmother Katrine Prela, who came to us and brought us dry food in Tepelena, we would have starved to death, like many of our comrades.

What do you remember of any other events from that camp?

One night, a young woman from Tropoja, Drane Jakaj, who was waiting to be released, went at night to open the grave of her child, who had died at the age of 5, since that family had come to that camp. Opening the grave with the spoon we ate the soup, she cleaned the bones with her dress and said: “Your mother will not leave you here, no”. The desolate woman was forced to break her son’s bones in order to hide them in her body clothes without being noticed by the camp guards, as she was not allowed to take them. That night my mother was with him helping her and then she was able to take her son’s bones and bury them in Theth.

When were you released from that camp?

In 1954, that camp was closed and we were sent to the Savra camp in Lushnja. Along with the others, my mother also worked up to the waist in the water to dry the Tërbuf Swamp. In one case, the mother was so attacked by beetles that she fainted, so much so that her friends dragged her ashore, knowing that she was dead. Tone Nuthi, with her sisters-in-law from Pjetroshani of Bajza e Kastratit, clashed with the police, who wanted to put their half-dead mother to work in the water, telling her: “Get up and work my criminal”!

How long did your mother work in those conditions?

In that job the mother worked for 3 years. In 1956, one day when a senior officer of the Ministry of Internal Affairs for inspection, Rrok Kont Marashi, came there, he taught me to come forward and tell him that I was innocent.

What did he teach you…?!

The count had written to me in a letter what I would say to the officer, and I did. I told him that my father had left me in my mother’s womb when he ran away and what was my fault?!

What did he say, did he answer you?

He was touched by my words and said they would study my work. After some time, the letter came and I was released when I was 8 years old while my mother remained there. My cousins came and picked me up from the camp and took me to the village. But even there they did not let me live, as the village was a border area and they took me to Kastrat, where I made 2 hours every day to go to school and 2 hours to return home. I finished the 8-year school excellently being the best student and I made a request to go to the “Tom Kola” Dormitory in Shkodra, but they told me: “Stay calm and shut your mouth, because you are the son of the criminal Mark Deçkaj. “Hold the pickaxe tightly and do not feel it.”

Where did you grow up after your mother was in exile?

By the time I was 16, my uncles raised me. At that time, I was an adult and realizing that I had no hope for life, I started thinking about escaping from Albania and going to my father.

Where was your father at that time?

Until then, my father was in Italy, while my grandfather was in Tuz, Montenegro, and we communicated by letter with them.

Did you have provocations and did the Security people follow you?

A person named Ndue Nikoll Markhelli, who was decorated by the Minister of Internal Affairs, Kadri Hazbiu, constantly provoked me, putting the radio on “Voice of America”, as if my father would speak. Likewise, he occasionally told me to run away together. I understood this provocation and never let them know that I wanted to escape. One day I told my mother (in 1959 she was released from exile) to run away together, but when she asked her mother, the grandmother said: “Do not leave her, because they will kill our son and take us all by the neck. “. So, my mother told me she was not coming and I should not leave. But I had decided it together with my two friends, Kol and Gjelosh Narkaj, and so we escaped.

How could you escape from Albania?

On June 13, 1966, the day of the feast of St. Ndout, I told my mother that I was going to church. In fact, together with my friend, Kol Narkaj, (Gjeloshi did not come because he was marrying his brother), who was a year older than me, we took the road and secretly went to Leqet e Hotit, down to Grabam and crossed the border leaving in Yugoslavia. There we were handed over to a house where we told the truth and they received us very well. That house had friendships with our family and they found the opportunity to announce that we had surrendered to them.

What happened next to you, where were they taken?

Then, according to the rules, they handed us over to the soldiers, who took us and sent us to the Leshkopolje prison, where they kept us for 2 months in the interrogator asking us. During that time, with the intervention of Rroko Keqi (from Tuzi), to the Yugoslav authorities, we were not returned to Albania, but were released and I went to my grandfather, Pjeter Deçkaj, who was in Tuz.

How long did you stay there?

I stayed in Tuz with my grandfather for 9 months and at that time, my father, who was in America, had done the paperwork and on February 27, 1967, I was granted political asylum in the United States. So, I left Belgrade for New York, where my father was waiting for me with a photo of me in my hand, which I had mailed to him.

How do you remember that meeting, can you describe it to us?

It was a touching meeting he had with his father at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport. Dad looked at me and I looked at him. When he approached me, I said, “Are you my father?” “Yes,” he said, “I only heard the voice once. I left you in my mother’s womb and said, ‘Will he be a boy?’ We were both covered. I said to him: “O Mark Deçkaj. Be strong, why are you crying?” As he kissed me, I said to him: “Now I am no longer poor, I am not without a father”!

But after your escape, what happened to your mother?

After I left, a year later, while my mother was in the mountains, spy Ndue Nicole Markhelli informed the police that her mother wanted to escape, and they came and took her and interned her in Hajmel, where she stayed for 19 years.

During the time your father Mark lived in America, was he involved in politics?

My father has been involved in politics since he was in Italy, where he was elected chairman of the “Independent National Bloc”, working closely with Ernest Koliqi, Gjon Markagjoni, Ismail Vërlac, Kol Bibë Mirakaj, etc. During that time, the men of the Albanian State Security made an assassination attempt on their father with a pistol, but he managed to escape wounded in the arm.

But after that, was there any more problem from the State Security people who were sent there on a mission from Tirana?

The assassination attempt did not last long, as even in the hospital they wanted to poison him with some biscuits, which were brought there by a woman dressed as a nun, who after the investigation of Ernest Koliqi, turned out to have left the Albanian Embassy in Rome. After that, Dad was forced to go to America.

What about your mother when you got together?

On August 16, 1990, when I was 42 years old, I came to Albania and met my mother who at that time lived alone in Shtoj. My father and wife told me not to come, because communism had not yet fallen, but I had decided, my wife came with me.

Did you have a problem coming, as the communist regime had not yet fallen at that time?

In Rinas I had a lot of problems and initially they did not want to stamp my passport, but after a debate of 15 minutes, they stamped me.

What did your mother tell you when you met?

I apologized to my mother and she told me that she had made me halal. After 5 weeks, I was able to send the letters to my mother and took her with me to Italy, where my father later came. So, after 42 years and 3 months, they met in Rome.

How do you remember that meeting?

It was a touching meeting where there were only tears. Dad and mom lived 3 months in Italy and then came to America where we all got together. I saw them when they cried for each other. When my mother saw how well we lived, she said, “Now I’m ready to die.” And so, it really happened: On Tuesday, July 2, 1991, they both lost their lives in a car accident.

What about you, when did you start the family?

I was married on October 22, 1971, to Lajde Mark Gjonaj, whose father, Pashuk Markgjonaj, comes from a nationalist family quite persecuted by the communist regime, just like us.

How many children do you have?

I have 3 sons: Robertin, Palin and Tomin, who is an assistant director and film producer in Hollywood, where he has collaborated in 34 films./Memorie.al