By Ali Buzra

Part Eight

LIFE UNDER PRESSURE AND SUFFERING

(EVALUATIONS, COMMENTS, NARRATIVES)

Memorie.al / At the request and wish of the author, Ali Buzra, as his editor and first reader, I will briefly share with you what I experienced during my encounter with this book. This is his second work (following the book “Gizaveshi through the Years”) and it naturally continues his established writing style. The sincerity and candidness of the narration, the simple and unvarnished language, the precision of the episodes, and the lack of – or failure to exploit – any subsequent, intentional imaginative processing, have in my opinion served the author well. He reaches the reader in his original form, inviting us to at least recognize unknown human fates and pain, whether by chance or otherwise, leaving us to reflect as a beginning of awareness toward a catharsis so necessary for the Albanian conscience.

Belul Balliu, son of Halil, was very wary of the State Security (Sigurimi i Shtetit), knowing they were looking for any pretext to arrest him. After 1945, when his uncle, Azis Balliu, was arrested and sentenced, Belul remained the head of the family. In 1946, they were labeled as kulaks. In 1947, by a decision of the District Presidency of the Democratic Front, this title was revoked. The communist state toyed with persecuted families. In 1952, by order of the District Party Committee, they were again labeled as kulaks.

In 1976, Belul, a father of three daughters, was arrested. By then, he had separated his household from Haxhi’s. After several months of investigation under constant torture and pressure, he was brought to trial and sentenced to 8 years in prison. He served his sentence in Ballsh, Fier. There, he fell seriously ill and was sent to the Tirana prison hospital, where he passed away.

Haxhi Balliu is the only person from this clan sentenced by the communist dictatorship who is a living witness today, with whom I have communicated directly. He is the son of Azis Balliu, born in 1931. He completed primary school in Zdrajsh. At the time of his father’s arrest, he was 15 years old. The burning of their homes and his father’s arrest were, for him, his first introduction to the communist state of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Initially, despite his father being in prison, he was accepted into the youth organization in the village. In 1951, he was mobilized for military service in a labor unit in Tirana, without the right to carry a weapon. In this unit were also the brothers Veli and Haki Biçaku from Qarrishta, as well as Sami Blloshmi from Bërzeshta.

After a year, he was transferred to Brar, a village at the foot of Mount Dajti. A military center was being built at Rrapi i Treshit. The labor soldiers transported stones by hand, carrying them on their backs. The quota was for each soldier to transport 2 cubic meters over a certain distance from where the stones were taken. Those who did not meet the quota were sent to the garrison, where a lime pit covered with a tarp had been improvised as an isolation cell.

There, at the unit, the decision of the District Presidency of the Democratic Front was confirmed to him: they had been labeled as kulaks again, while his father was still in prison. “When my stepmother came to visit me,” Haxhi recalls, “my back was covered in lumps from the stones.” Regarding his time as a soldier, he recounts an event that testifies to the fact that among the communist leaders, there were also temperate men. One day, the Chief of the General Staff of the Army, Petrit Dume, originally from Kolonja, came to his unit for an inspection.

It was well known that this unit contained soldiers from families with “bad biographies,” as they were called at the time by the communist regime. After requesting that all soldiers gather, he told the unit officer to separate those from Kolonja. He began to ask each of them their name and which village they were from. He stopped at a soldier named Estref Hasani. “Whose son are you?” he asked. “So-and-so’s,” he replied. “Your father killed my brother and crippled my arm,” Dume told him. “You are tainting the uniform!”

“Are you finished, Comrade Commander?” the soldier said, without flinching. “I was a child then and know nothing of this, but you should have killed my father back then. He is in America now!” Revolted, the Chief of Staff of the Albanian Army, Petrit Dume, lashed out at everyone with insults, telling them: “You have come here to pay for your fathers’ debts.” Another day, the Minister of Defense, Beqir Balluku, visited. After asking the soldiers where they were from, he stopped at Haxhi, and upon learning his origin, said jokingly: “Is that vodha (sorb tree) still there in Funarës?”

(During the war, Beqir Balluku was the commander of the Second Brigade, whose units were crushed by the National Front (Balli Kombëtar) forces led by Isak Alla at Qafë Drizë. The forces of the 2nd Assault Brigade had received orders from Enver Hoxha to attack the villages of Funarës, Zgosht, and Letëm to eliminate the nationalist forces.)

Among other things, Minister Balluku told the soldiers: “We haven’t brought you here for revenge, but because we have a need.” One of the soldiers told the minister: “Isn’t it a shame for a soldier to go out in this uniform?” They were all in torn and old military clothes. On this occasion, the Minister ordered the officer to supply the soldiers with new clothes, from hats to shoes, and it was done.

“One winter day,” Haxhi recalls, “they gathered the soldiers and asked who master stonemasons were.” Haxhi raised his finger along with Sali Balliu, the son of the younger Mustë Balliu, who was with him. They were sent to Rrapi i Treshit, where construction was taking place. There they worked as masters, along with the brothers Haki and Veli Biçaku, escaping the labor of transporting stones.

Sometime later, a sergeant, observing Haxhi closely, took a liking to him and made him a cart driver in the unit’s logistics department, where he worked for a year. Thus, “kulak” Haxhi Balliu suffered no more in the army. After being discharged, he married a girl from Qarrishta. In 1958, he and Belul separated their households.

For several years, Haxhi worked as a laborer in Bizë, Martanesh. After the establishment of the agricultural cooperative, “kulak” families continued to remain outside the cooperative, as the order was not to accept them. The cooperative system across Albania was established not on a voluntary basis, but through sophisticated forms of coercion. To present it as an advanced economic process, kulak families were initially not accepted, in order to segregate them from others. At the end of 1967, when collectivization was completed nationwide, the “kulaks” were finally admitted.

The cooperative form in agriculture was the most enslaving method for the peasant, stripping him of the ancestral property he inherited. We will not dwell on this, as it is a subject of its own requiring separate treatment. In 1968, Haxhi began working in the cooperative along with his family. The State Security Operational Officer covering the area followed and surveilled him constantly. They were only waiting for a pretext to arrest him.

They sent him to the most difficult work fronts in the cooperative, but knowing the situation, he did not resist. He was physically strong, and in the circumstances he found himself, he had to endure any kind of work. He had to support his family. God had blessed him with a bunch of children who were minors. He married off his eldest daughter in Dragostunjë to Refat Gurra, the son of Shaban Gurra, who was also labeled a kulak. The Security Operational Officer summoned him and said: “Why did you marry your daughter into the Gurra family? He is a greater enemy than you!” “I married her because she was of age to be married!” he replied shortly.

The cruelty and treachery of the State Security knew no bounds. The last scion of the Balliu family was marked for punishment. Haxhi was a smart, courageous, and dignified man. These manly traits made him an eyesore to the Security personnel and their tools. On November 14, 1976, the courier of the Lunik military battalion came to him and told him to go with him to Librazhd, to the Military Branch. With the vehicle of the Kuturman cooperative, they both went down to Librazhd at night. In the morning, he presented himself at the Military Branch.

The officer who received him told him: “You will do your zbor (reserve training).” (At that time, every capable citizen performed several days of military training at designated units, known as zbor). Haxhi clarified to the officer that he had already completed his zbor for 1976. “Then you will do it for next year,” the officer cut him short. Haxhi felt that everything was planned. Thus, he set off “to do his zbor” in Babje, at the military unit.

After crossing the Shkumbin Bridge, on the road turning toward Babje and Polis, a “Gaz” vehicle of the Department of Internal Affairs stopped at his feet. The door opened immediately and out stepped the head of the Department, the deputy head, and the area operational officer. The deputy head said: “In the name of the people, you are under arrest,” while the head intervened saying: “It’s not for an arrest, we just have some things to discuss.” Understandably, these were their games. They threw a blanket over his head, put him in the car, and took him to the police post-command in Qukës. For seven days and seven nights, they kept him there, pressuring him. The area operational officer, who had been following Haxhi for a long time, told him: “Confess, you have children, so you can go home in peace. You aren’t talking, but you will see what happens in Librazhd.”

After seven days, he was sent to Librazhd and put in “Cell Seven,” which was the women’s dungeon. Under pressure and torture, they demanded he admit to having spoken with fugitives, to give information about Xhem Balliu, and to explain Ferit Dosku from Dorëzi, who had been a fugitive for years. Ferit was married to Haxhi’s sister.

They told him that Ferit had come from America and spoken with him about escaping. “Tell us about Qemal Balliu, what did he discuss with Adil Biçaku?” Adil Biçaku from Qarrishta, who had completed the “Normale” school for teachers along with Qemal Balliu, had escaped a few years earlier and was in Sweden.

They questioned him about people they suspected in Funarës, wanting him to tell what he knew about them. He remained alone in the dungeon for nine days. Mihane Çerri was arrested with the “Bërzeshta Group” and brought to “Cell Seven,” while Haxhi was moved to “Cell Two” with Bedri Blloshmi. “Belul Balliu,” he recalls, “was in a cell with Genc Leka, while in ‘Cell Three’ were Vilson Blloshmi with Iliaz Balliu and Arif Çota, the latter two from Funarsi.” As can be seen, dozens of the Balliu family were arrested.

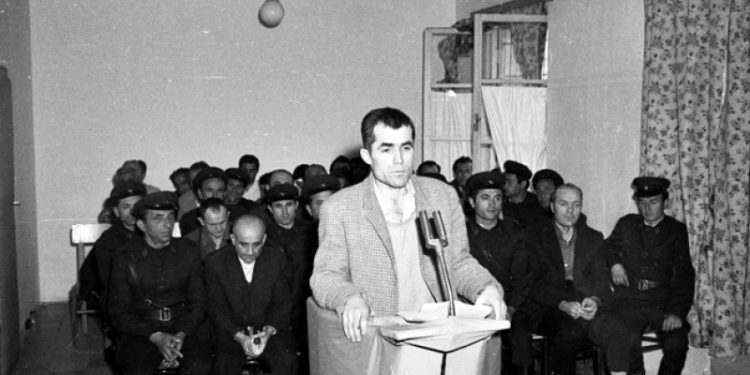

He went on a hunger strike for four days, but no one cared. After four days, he began eating with Bedri. Haxhi Balliu spent nearly 4 months in investigation. They proposed collaboration, attempting to turn him into a Security informant by promising his release, but he remained dignified and unconquered in the face of threats and inhuman torture. After three months and 27 days in the dungeon, he was brought to trial. His trial was held in two sessions.

Having no connection to the charges brought against him, he stood up several times in court and told the trial panel: “This trial is unjust,” and demanded justice. “If there is justice,” he reacted, “the lying witness will be punished and I will be released.” One of the testimonies given against him was that, while cleaning a canal in the cooperative, he had said the cooperative would fall apart.

“Allow me to ask the witness a question,” Haxhi requested. They allowed him. “In which year did we work on a canal together in the cooperative?” he addressed the witness. The answer was 1973. “Is it with these witnesses that you seek to convict me? In 1973, I was in a state enterprise and don’t have a single day of work in the cooperative; look at the payrolls!” he said.

Another testimony was that he had said: “I have many children and they can’t be fed with bread in the cooperative,” etc. Such expressions might have been used at the time, but how can a man be sentenced for that? The cruelty and treachery of the communist dictatorship truly surpassed all human reason, leading people into absurd and senseless situations. Years later, one of the assistant judges from a neighboring village told Haxhi a detail: “When they retired to make a decision, the chairwoman of the trial panel put her hands to her head.” Truly, the judges were under the pressure of the party-state.

Haxhi Balliu, 45 years old, father of six children and one yet to be born, was sentenced to 7 years in prison on fabricated charges. On the day of the trial, his wife and eldest daughter arrived. At the moment of meeting, the daughter and wife would not stop crying. Haxhi turned to his wife: “Do not cry, but serve the children, for I and the government know my affairs.” Truly it was so, since both Haxhi and the “government” knew the sentence was without facts, but the son of Azis Balliu could not be left unsentenced – he who seemed to be defying the servants of the dictatorship.

After the verdict, he was sent to Prison 313 in Tirana, where he stayed for a month. There he met Lipe Nasho, the former director of the Fier Oil Plant, as well as an oil engineer from Skrapar, Nuredin Skrapari. Later, he was sent to the Spaç camp in Mirdita. At the entrance of the mine gallery, Haxhi asked what the quota was there. One of the prisoners told him: “If you don’t pull out 22 wagons of mineral ore, you will stay tied up all night, and you’ll still come back to work tomorrow.”

Serving his sentence in Spaç alongside him were Fatos Lubonja and the son of Beqir Balluku, the former Minister of Defense who had been executed by the communist regime. “We helped Beqir’s son, Vladimir, to pull out the wagons,” Haxhi recalls, because he was unable to do it. After the 1981 student demonstrations in Kosovo, the Albanian government issued an amnesty for prisoners sentenced to less than eight years. Thus, in 1982, he was released, having served 6 years of his 7-year sentence. He returned to his family at the age of 51. He stayed home for 4-5 days and then went to work in the cooperative. Surveillance continued, and he remained a “point of reference” for the State Security employees.

Former political prisoners, in secret, would joke with each other, mockingly targeting the dictatorship. One day, Haxhi’s wife, upon leaving the cooperative’s bread shop, spoke out in revolt because the bread crust was burnt, saying: “They are giving us burnt bread.” Tafil Luka, a former prisoner sentenced to 12 years for “treason against the fatherland,” heard her and approached, speaking in a low voice: “Give that burnt crust to Haxhi to eat, and tell him to behave, for he knows the place (prison).” This state of affairs continued until 1990-’91.

With the overthrow of the communist dictatorship, the Ballius of Funarës were liberated from their chains, as was everyone else—they who for 45 consecutive years were persecuted, sentenced, and felt isolated and despised by the servants of the communist state. However, it must also be mentioned that the people of Funarës loved and valued them in their hearts, but under the conditions of the fierce dictatorship, they were forced not to maintain relations with them.

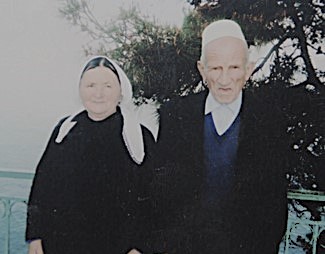

Today, Haxhi Balliu, 88 years old, the last victim of the legendary and martyr clan of the Ballius, lives in Funarës with his wife and his son Qerim, enjoying the grandchildren and great-grandchildren God has granted him. I heartily congratulate him for the help he has provided. / Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue