By Prof. Alfred Uçi

Part One

– Migjeni, in the Whirlwind of Untruths and Speculations –

Memorie.al / “At the burial of old idols, the bells shall crack from tolling, the minarets shall break their backs from bowing, and the vocal cords of the priests shall snap from singing. And silence will come. For every outcry begins and ends with silence. Afterward, work shall begin.” (From “Idols Without Heads” – Migjeni)

History works fundamentally, being merciless. Through its seemingly absurd and paradoxical play, it does its job well, astonishing the generations to come with the rigorous selection of its sieve: ultimately, it puts everything in its proper place. It topples figures forcibly raised on pedestals; it scatters the false glow of halos even when they are embalmed to be preserved eternally in its bosom; it flings them away like chaff and finally abandons them to oblivion.

But history also works in another direction: it anchors in its memory figures who seemed buried, never to be heard or felt again, and places them on a deserved pedestal, albeit late. Miraculous is its re-evaluative power, discovering hidden treasures where they were least expected and returning them to the future, enriching generations to come.

The last half-century was enough for history to place Migjeni’s literary work on one of the highest peaks of the evergreen mountains of our national literature.

The “Comet” Fallacy

Migjeni’s poetic spring flowed briefly because he died young, at the age of 27, leaving behind a small literary heritage in terms of quantity. This fact apparently led some, who wished to predict Migjeni’s place in our literary history, to call him a “comet” that emits a momentary flash and then fades. The comparison was wrong, because Migjeni’s literary legacy has illuminated and will continue to illuminate like an unquenchable sun. Despite this assertion, one cannot say that the entire spectrum of Migjeni’s literary radiation has been captured or understood. This spectrum includes many values yet misunderstood, which are like invisible infrared rays that the human eye cannot perceive.

In a shallow view, it might seem that Migjeni, a poet honored in recent decades, has taken his full, exact, and unchangeable place in the pantheon of our national literature. But it is not so; there are two important reasons that make it necessary and useful to review the evaluation of his literary work once again.

- Changing Social Conditions: It is of interest to see how Migjeni appears against the backdrop of today’s democratic processes.

- Ideological Dogmas: The evaluations of Migjeni’s creativity have not escaped the influence of those schemes and dogmas that guided official Party criticism, which sought to pull him into the whirlwind of political utilitarianism.

The “Scapegoat” of Socialist Realism

We know well the efforts made to baptize Migjeni as the “first authentic representative of socialist realism” in Albanian literature! In this case, our poet was used as a “scapegoat” (kokë turku), as long as, according to Party ideological criteria, the name of the condemned “Lame Kodra” (Sejfulla Malëshova) could not be mentioned.

However, many forgotten facts show that one of Migjeni’s greatest anxieties – experienced strongly, emotionally, and even dramatically – was his long-drawn effort not to slide into the political and ideological “games” of the time, to not become their prey. He showed strength of character, high civic honesty, and a deep aesthetic understanding of the writer’s mission, closing his doors to those “freezing winds” coming from the “right” or the “left,” which the poet feared might “extinguish his light.”

A Position “Outside the Game”

Migjeni’s literary work is the most authentic and convincing document proving his “offside” (jashtë loje) position. Maintaining such a position was not easy for a poet lured by “siren calls”; it was even harder for an “engaged writer” (in Jean-Paul Sartre’s terms) who yearned for the sad stagnation and social equilibrium that kept the Albanian world far from the civilizing progress of the time to be broken.

Other talents, even of his rank, found it easier to distance themselves from the incandescent ideological atmosphere of the 1930s, even by remaining silent. Migjeni found it harder because he was searching for paths of salvation. Like an incurable disease, the question gnawed at his soul: Where should we go?

Vulgar criticism used banal arguments for the poet’s answer. By manipulating a symbolic artistic figure – the “allegorical sun” – this criticism attributed to the poet the choice of the Soviet Union as the way out and the model for the future. Yet, when relations with “Soviet revisionism” broke, even this core figure was forgotten.

Migjeni was invited toward this model by representatives of communist groups of that time, among whom he distinguished honest people, but also shallow dreamers and incorrigible visionaries, who, even unintentionally, could ruin the country. He did not see in their ranks flag-bearers with sufficient intellectual or moral potential to follow.

The Irrational Forces of History

Migjeni himself had a broader and deeper conception of life; he understood that it does not move according to the desires, however beautiful, of visionaries. Like many others, he had been disillusioned by the rationalist illusions of the Enlightenment; the social experience of the 20th century’s shocking dramas had taught him that on the stage of history, terrifying irrational forces dance and “play their game” with humanity. They pull it into extremely dangerous adventures and tragedies of apocalyptic proportions. This is why the poet was wary of following visionaries.

Other social forces also called Migjeni to their side, needing to set up a grand decor and paint the facade of the “Kingdom of Salep Sultan” (King Zog’s regime). A flirtation with the Monarchy would have been not only socially dangerous but also humiliating for a creator who stood steadfastly on the side of the people and could not play the role of court poet. For his unforgivable refusal, the Zogist regime twice condemned the poet to death: first, when it banned the distribution of “Free Verses” (Vargjet e Lira), and second, when it left him at the mercy of fate in the face of his deadly disease.

Against the “Mighty Fist” and the Superman

Vulgar criticism, instead of mentioning the bitter experiences of the poet who suffered like Christ for all human tribulations, labeled him a “pessimist.” But what was the poet to do? Laugh like a clown while his heart broke with grief?

The totalitarian state accepted Migjeni as its official poet, but the regime played a dishonest game. They accepted him only on the condition that he serves the regime – that his ideal be identified with the regime’s ideal. Party criticism gave this meaning to the poem “Let the Man be Born” (Të lindet njeriu). But how far was the “Commander” (Enver Hoxha) from Migjeni’s “Man without a star on his forehead.”

Criticism also speculates on Migjeni’s relationship with Nietzsche, turning it into a kind of “biographical trap,” almost suggesting collaborationist sympathy for Nazis. It is true that in the 1930s, forces sought to pull the Albanian intelligentsia into the fascist adventure. But Migjeni stood in irreconcilable opposition to the myths of fascist ideology. In the poem “The Shapes of the Superman” (Trajtat e Mbinjeriut), Migjeni revealed the danger of these myths. To him, the myth of the superman was terrifying: “A deceptive sphinx, the future Superman / Without a heart, without feelings / His lightning eyes / Circle the globe aiming grimly.”Revolution or Evolution?

Some try to call Migjeni a “revolutionary,” implying a man of violence. But was he truly so? As a fragile human nature and a poet, he could not be. This did not prevent him from being an opponent of social injustices, but a “revolutionary” who adores violence, he was not. By liberating him from the incense of Stalinist ideology, we must learn to understand that a man can be very good without being a revolutionary of that type.

Migjeni transformed his internal bile into poetic verses that live forever, beyond “revolutionary turns.” He feared social cataclysms and preferred evolution, which has as its driving force the spiritual and intellectual perfection of man. He feared “radical social upheavals” because he knew they could spin out of the control of human reason and turn against man.

A Landmark of Modernity

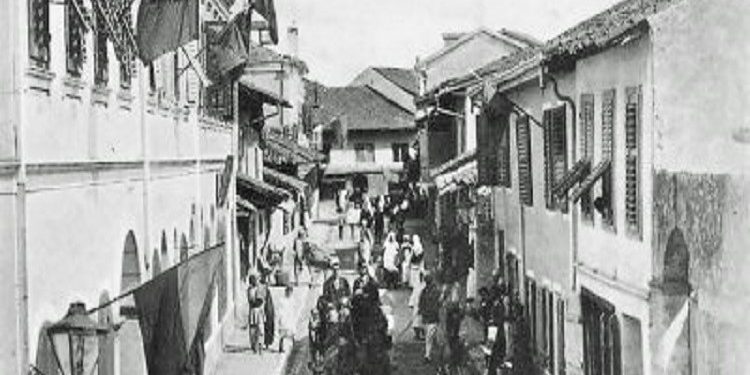

Migjeni’s work is a reference point that reveals key moments in the history of Albanian literature. In the 1930s, Migjeni gave literature the social and aesthetic weight that the poetic words of Naim, De Rada, Fishta, and Çajup – and later Fan Noli and Lasgush Poradeci – had during the National Renaissance.

He was the most modern writer of the 1930s. He was modern because, like no one else, he developed the critical-social spirit that distinguished 20th-century world literature. His work was the most important manifestation of social realism, distinguished by its demystifying spirit. Unlike the idyllic representations of anachronistic writers, Migjeni revealed misery (mjerimi) as the fundamental attribute of life and the Albanian reality of the 1930s.

In Migjeni’s work, misery is branded as a shameful stain on the forehead of society, history, and the centuries. In the Albanian soil, according to the poet, there is no place for fairies or mountain nymphs, for other beings dance the dance of misery. Migjeni did not idealize history; he poeticized it. He was not attracted by accidental or concrete historical events, but by their global meaning and experience./Memorie.al